As coronavirus spreads, medical workers in Mexico face attacks, intimidation

- Share via

MEXICO CITY — Esther García was walking toward a bus stop after completing her shift when a young man approached her. Then he tossed a plastic bag filled with liquid at her.

The bag struck the left side of her head, splashing her face with its caustic contents — a mixture of water and bleach. The attacker ran off as Garcia felt burning in her eye and her vision went blurry.

“I was filled with fear,” she recalled. “I started to cry. I didn’t understand what was going on.”

This wasn’t a revenge attack, a crime of passion or some kind of message from Mexican organized crime.

García is a nurse at a public clinic outside Mexico City.

Health workers, especially nurses, have been targeted across the country in recent weeks by assailants accusing them of spreading coronavirus, according to health professionals and authorities.

Apart from being sprayed with bleach, they have faced verbal assaults, been denied seats in public transport and been blocked from entering their own communities.

“You are spreading COVID!” is a common slur.

Indian medical workers are treating coronavirus patients without adequate equipment. One doctor warns of ‘mass desertion’ in the healthcare system.

Mexican authorities, including President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, have condemned the mistreatment and stressed that it has been perpetrated by a scattered minority in a country where most citizens have lauded the workers on the front lines of the pandemic.

“It is truly outrageous that anyone would attack health personnel because of fear of COVID-19,” Dr. Hugo López-Gatell, who heads the government’s coronavirus-response team, tweeted this week. “They are here to protect us. Our total gratitude.”

In the southern state of Oaxaca, lawmakers passed a new statute mandating nine-year prison terms for assaults on medical professionals.

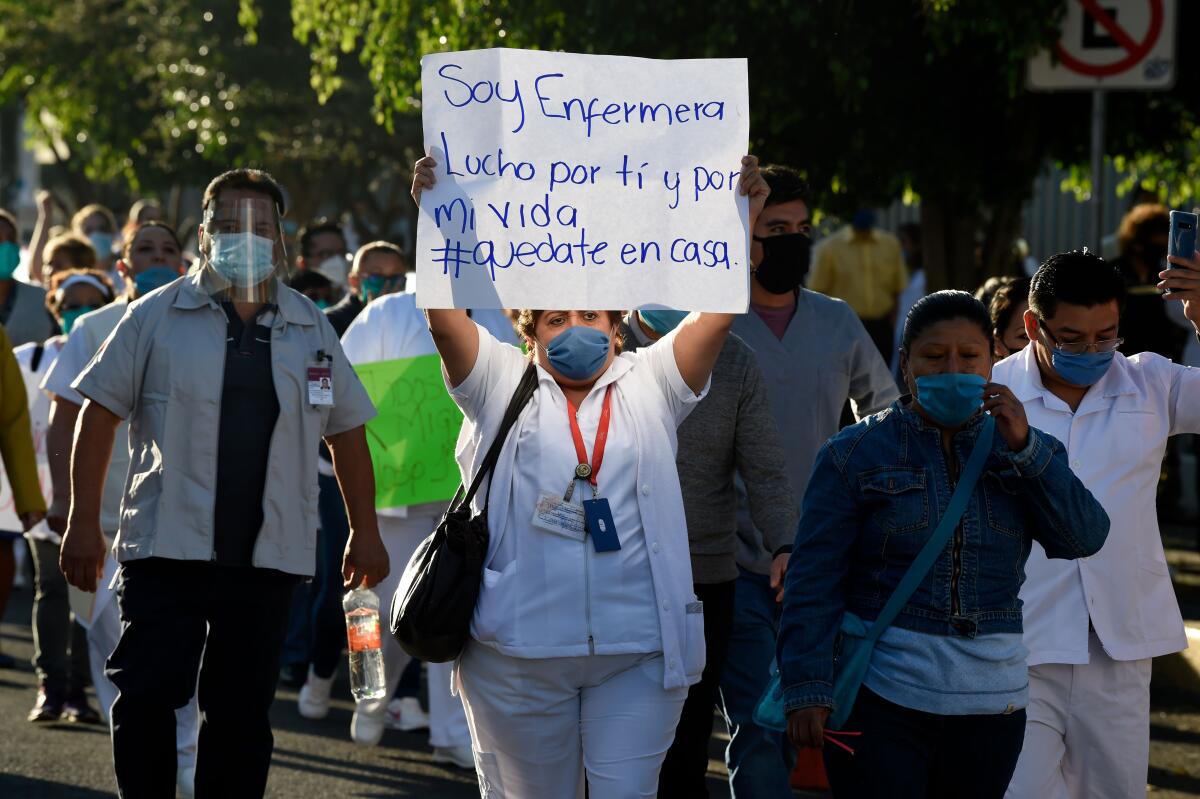

The medical workers are already risking their lives to care for COVID-19 victims. Across Mexico, doctors, nurses and others have staged protests against a lack of protective gear, supplies and medicines.

More than 500 health workers have already been infected, authorities say, and at least nine have died. Outbreaks have been reported in at least four public hospitals — in Tijuana, near Mexico City, in San José del Cabo and in Monclova, in the northern state of Coahuila.

The reports of infected health workers have left a stigma, stoking fears on social media and elsewhere that they are vectors of contagion.

In western Jalisco state, at least six nurses have been victimized, including one who, like García, was showered with water and bleach, according to the state nursing association there.

“As health workers we have confronted disinformation and panic — even physical and verbal aggression,” Edith Mújica, president of the group, told reporters.

“We are not enemies. … People should know that just because we are nurses that is not to say that we are contaminated.”

Across Mexico, townsfolk have thrown up “sanitary” roadblocks — staffed with self-styled health vigilantes — to prevent entry of outsiders and other potential virus carriers. The barriers have meant some health workers cannot get home, forcing them to move.

In one case, reported Mexico’s Reforma newspaper, residents denied a nurse entry to her neighborhood in the Pacific coast town of Bahía de Banderas, in western Nayarit state.

“We don’t deserve this,” the nurse, Melody Rodríguez Navarrete, said afterward. “We are not asking them to praise us, only that they understand that we are here to help them. It’s our work and everyone is taking the appropriate measures not only to avoid becoming infected, but to avoid infecting others.”

Along with outrage, the assaults on health workers have prompted considerable national soul-searching about the collective mentality behind such misguided behavior.

“The assaults demonstrate an accumulation of contradictions in our society,” columnist Javier Solórzano Zinser wrote Friday in La Razón newspaper. “Those who are being attacked put all their determination and knowledge into resolving problems, not into provoking them.”

Mexico is not alone in the disturbing phenomenon. Similar attacks against health workers have been reported in India and elsewhere, including the United States.

Traditionally, nurses and other health workers in Mexico have been figures of considerable respect. On crowded public buses and trains, people routinely give up seats to nurses in white uniforms and health workers in lab coats.

Now, to avoid drawing scrutiny, health-sector commuters are being advised to wear civilian garb on public transportation, and to change clothes at their workplaces. In some cases, authorities are arranging dedicated transport to shield workers from ill-treatment.

In Mexico City, unions representing transit workers and health employees this week launched a special bus service for employees at seven public hospitals.

“They are victims of attacks despite the fact that they are at the front lines of the battle,” Gerardo García, secretary-general of a health workers local, told Reforma.

In the case of Esther García, 46, who has been a nurse for 18 years, her vision returned to normal, but the bleach assault has left a legacy of fear and distrust.

She is a divorced single mother of two daughters, ages 19 and 17, whom she helps support on her nurse’s salary of about $700 a month. Like many fellow health workers, she cannot afford to leave her job.

“I don’t even want to think about what would have happened if they had a gun or some other weapon, instead of just bleach,” García said. “I feel very sad. … In this profession one recognizes that you run the risk of contagion of some illness. But I have never before felt fear that I would be attacked because I was a nurse. Never before.”

Sánchez is a special correspondent. Special correspondent José María Alvarez in Oaxaca contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.