Attack on U.S. Embassy in Baghdad underscores America’s polarization — and peril

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Few images are more haunting to the collective American psyche than the sight of a U.S. diplomatic installation under siege somewhere in the world. Such attacks have been a watchword for trauma: Saigon. Tehran. Beirut. Nairobi. Benghazi.

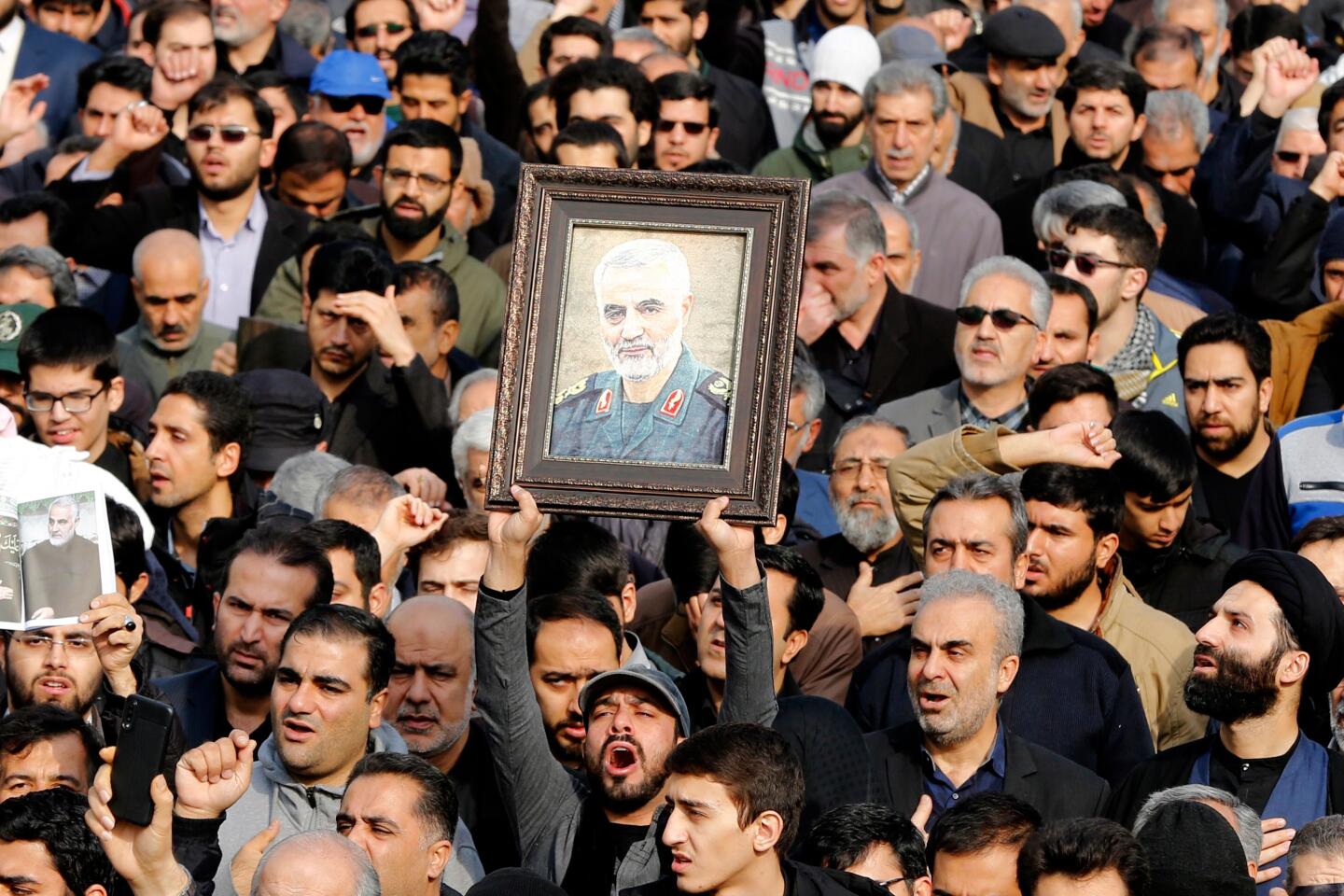

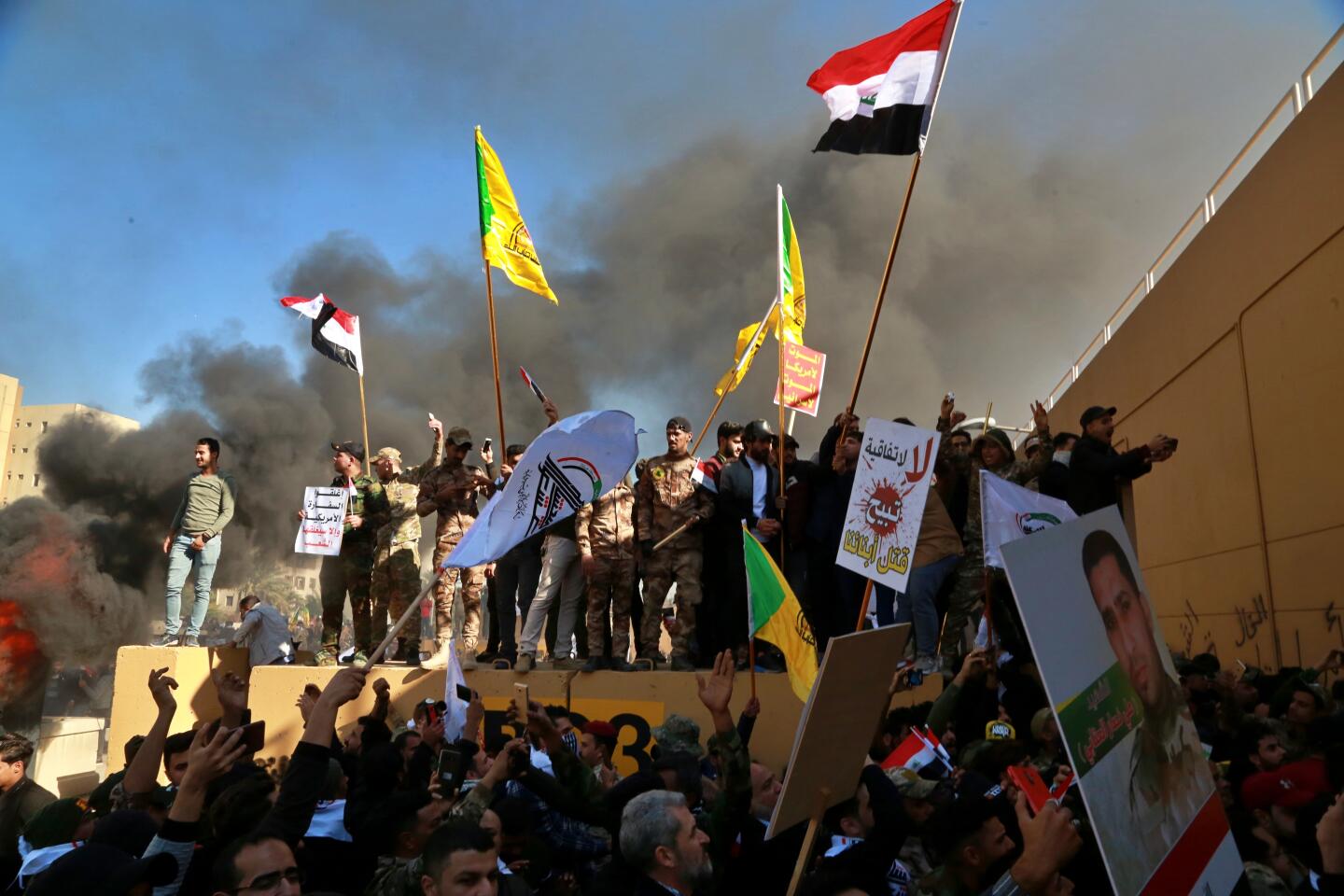

This week’s breach of the sprawling U.S. Embassy compound in Baghdad by supporters of a pro-Iranian militia ended on New Year’s Day when the militia called off the siege. The episode lasted less than 48 hours; core areas were not penetrated; no injuries were reported among diplomatic personnel or U.S. forces guarding the facility.

Yet for many, the attack in the Iraqi capital evoked a visceral reaction, a swirl of sentiments reminiscent of far more serious strikes against U.S. diplomatic personnel and facilities — ones that resulted in death, destruction or prolonged sieges. And for those who have lived through such an episode, the memory lingers long after an angry mob’s shouted chants have faded away.

“It’s pretty frightening if you don’t know someone’s going to come and help you — in our case, we were afraid they’d just burn it all down,” said Christopher R. Hill, who was the U.S. ambassador in Macedonia when the embassy was surrounded and outbuildings set aflame in March 1999.

For most Americans, still or moving images of U.S. embassies or consulates in distress — a volatile crowd scaling the embassy wall, the charred aftermath of a devastating explosion — have a certain dreamlike familiarity. The sight of U.S. helicopters taking off from the roof of the Saigon embassy carrying desperate evacuees in 1975, or of American hostages paraded by their student captors in Tehran in 1979, become part of a deep database of shared experience.

Such scenes also summon up other disquieting themes: the sense of a great power’s momentary vulnerability, the jarring realization that serious political miscalculations might have been made, and a creeping awareness of just how dangerous, in the long run, even a passing blow to American prestige can be.

Because a diplomatic installation is a physical embodiment of the homeland it represents, an attack against one reverberates like a clap of distant thunder. And with social media as an amplifier, actors the world over — protesters, militias, government-sanctioned thugs — are keenly aware of the propaganda value of an attack on a symbol of American might.

“We are the big dog, and that is how our enemies can get at us,” said Ryan C. Crocker, a diplomatic veteran of crucibles of conflict such as Iraq and Syria. In three of his ambassadorial postings — Lebanon, Afghanistan and Pakistan — a predecessor was killed.

Not every attempt to harm U.S. diplomatic personnel or damage American installations makes world headlines. But such attacks have punctuated modern U.S. history. A total of six ambassadors have been killed since World War II, and more than 100 diplomats and other U.S. government personnel have died violently while serving overseas since roughly the same period, according to the American Foreign Service Assn., the diplomatic union.

In the Baghdad embassy attack, some ex-envoys noted with dread the rapid politicization of events surrounding it. The template for such toxic partisanship is Benghazi — the 2012 attack on two U.S. facilities in the Libyan coastal city that killed the U.S. ambassador, J. Christopher Stevens, and three other Americans.

The violent episode was wielded by congressional Republicans a cudgel to attack Hillary Clinton, who was secretary of State at the time and later the 2016 Democratic presidential nominee.

Even as the Baghdad siege was still unfolding, President Trump was quick to take to Twitter to boast that the attack was the “anti-Benghazi.” He echoed that contention at a lavish New Year’s Eve party at his Florida estate, Mar-a-Lago, where he told revelers that “this will never, never be a Benghazi.”

Several former diplomats warned that the president’s remarks — coupled with last week’s U.S. airstrikes against the Iranian-backed Kataib Hezbollah militia, whose calls for vengeance triggered the embassy attack — were premature, provocative and risked inflaming the crisis.

“Instead of urging calm & restraint on all sides, Trump sees a combustible situation & lights a match,” Suzanne DiMaggio, a fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, wrote on Twitter. “Another unforced error.”

Scott R. Anderson, a former State Department lawyer based at the U.S. Embassy in Iraq, concurred. “Make no mistake: this was an old, familiar trap — and the Trump administration stepped right into it,” he tweeted.

Perhaps mindful of the political optics if the embassy situation had deteriorated, Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo, who had been set to leave Thursday on a swing that would have taken him to countries including Ukraine, was instead staying in Washington to monitor events in Baghdad, the State Department announced.

Envoys worry that a go-to approach of turning any attack into a partisan domestic battle back home makes it far more difficult and complex to balance the inherent risks of a diplomatic presence in a turbulent country.

While it is crucial to examine lapses of security practices and learn from them, Crocker said, he called it “ruinous to the conduct of diplomacy” to give adversaries the notion that an attack will result in diplomatic pullbacks in the country in question, and bitter infighting back in the U.S.

“You can’t eliminate risk — you can only manage it,” he said.

One obvious impact of high-profile attacks on diplomatic installations has been the heavy fortification of embassy and consulate compounds spanning the globe. Al Qaeda’s attacks against U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998 helped spur the move to construct fortress-like installations, with layer upon layer of intense security. While making diplomats safer, this can make embassies and consulates far less accessible to average citizens of host countries, hampering outreach and sometimes fueling a sense that America is trying to wall itself off from the world.

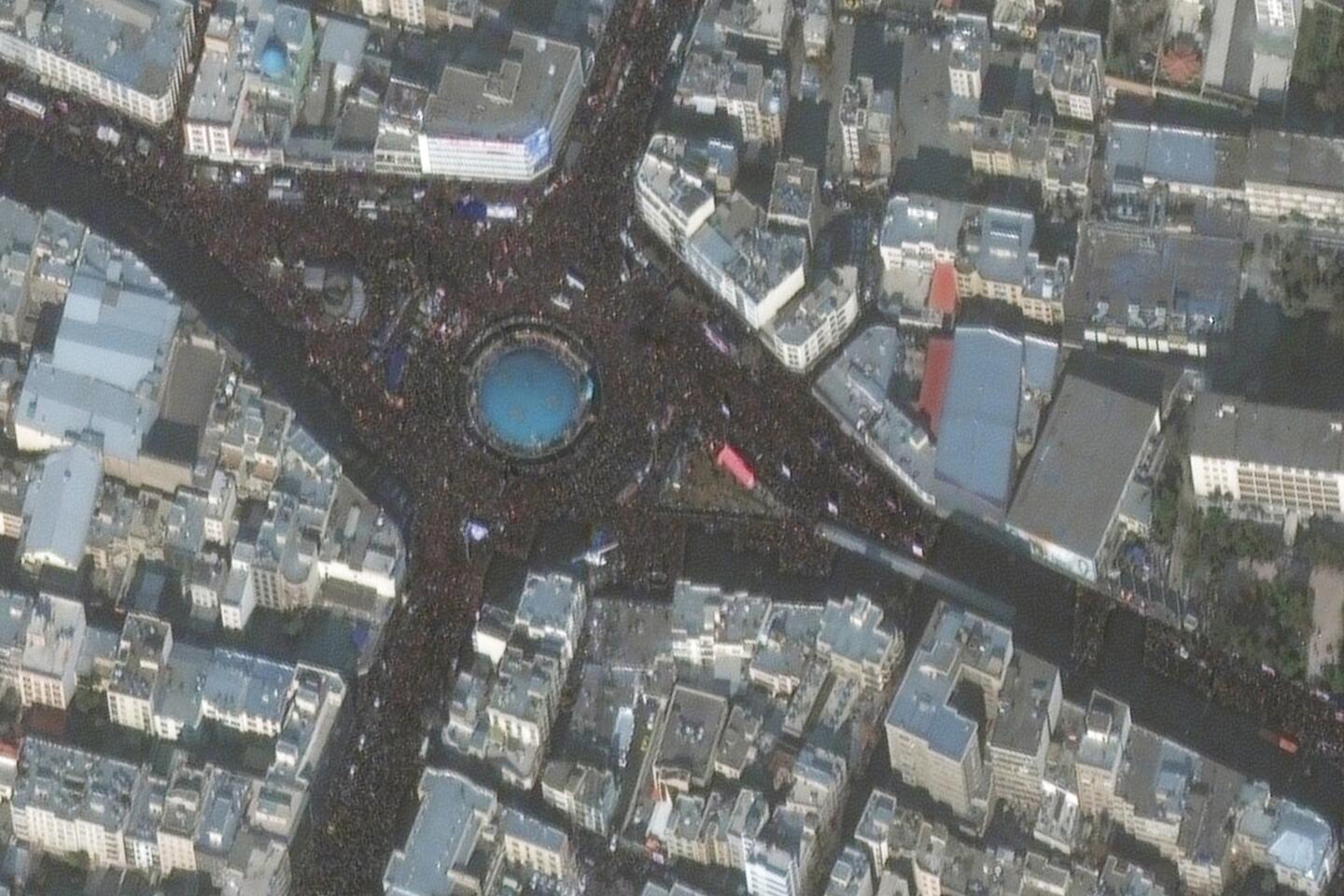

The Baghdad embassy is a case in point. The 104-acre compound in Baghdad dwarfs the size of U.S. diplomatic missions elsewhere. It has its own security teams, power stations and water facilities; it once housed some 16,000 people.

Hill, the former ambassador to Macedonia, who also served in Kosovo, Poland and South Korea, said host countries can find themselves in “fraught situations” as they try to determine whether demonstrators are merely blowing off steam over U.S. policies, or whether an installation and those inside are in real danger.

“You see riot police and someone gets hurt and the situation gets inflamed,” he said. “Governments often just think if they can prevent an attack on the buildings themselves, avoiding anything lethal, it’ll blow over.”

Crocker, who survived the deadly 1983 bombings of the U.S. Embassy and Marine barracks in Beirut, said the experience was formative to him as a diplomat.

“Bad things happen, and when bad things happen, you’ve got to keep going, otherwise you create a situation where you’re incentivizing further attacks,” he said.

Crocker, who went on to a career in academia after his retirement from the Foreign Service, criticized Pompeo for closing the U.S. Consulate in the southern Iraqi city of Basra last year after threats and rocket fire from Iran and Iranian-backed fighters.

“That tells the Iranians that all they have to do is make threats — they didn’t even have to breach the embassy wall,” said the former envoy. From the Beirut bombings and other attacks, Crocker said, the lesson he absorbed was to “lean into it — don’t let the bastards win.”

Times staff writers Tracy Wilkinson in Washington; Nabih Bulos in Amman, Jordan; and Shashank Bengali in Singapore contributed to this report.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.