- Share via

GOLDEN, Colo. — The gunman paced the hallways of the charter school, passing framed paintings of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson before stopping outside classroom 138. There, he took a deep breath, yanked open the door and began firing.

“Shooter!” shouted someone inside the classroom. “He has a gun!”

Two people seated at desks near the door jumped up and rushed the perpetrator, pinning his legs and arms against a wall, while everyone else sprinted out.

It was over in 15 seconds, and tiny yellow Nerf balls sprayed from the toy rifle littered the room. One of the men who rushed the gunman was struck in the thigh by a ball, a reminder of the personal danger involved in confronting an armed assailant.

The recent exercise was part of a two-day, $700 active shooter training course being offered at schools and churches across the country by an Ohio-based firm founded soon after the 1999 Columbine High School shooting rampage, which took place just a few miles from here.

The ALICE Training Institute, whose instructors have law enforcement or military backgrounds, provides courses for educators, church workers and small-business employees concerned about how to react if catastrophe strikes.

In packets handed out at its training sessions, the company says its aim is to empower “individuals to participate in their own survival using proactive response strategies in the face of violence.”

ALICE — which stands for Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter and Evacuate — was established by a retired police officer and has held sessions in roughly 3,700 K-12 school districts nationwide, as well as more than 1,300 healthcare facilities. Dozens of companies across the U.S. offer training for dealing with active shooters.

Standard shelter-in-place advice — “locks, lights and out of sight” — came into vogue after Columbine, when two students killed a teacher and 12 schoolmates. But that has been changing since federal education officials issued a report in 2013 suggesting staff (not students) should seek to counter shooters as a last resort.

While there’s no official database tracking instructional methods, the focus of courses across the nation has been shifting to a more “options-based” approach, analysts say.

Many trainers now promote a less passive philosophy that includes running, if possible, and fighting back, if warranted. Companies acknowledge the potential for death or injury, but say that declining to act can itself carry grave risks.

“Having a plan can mean the difference in life or death,” Andrea Nester, an ALICE instructor, told her class of about two dozen school officials, hospital workers and small-business owners.

: :

On a recent afternoon inside Golden View Classical Academy, Nester — a U.S. Army veteran who served in Iraq — asked the students, “Why are you all here? Just blurt it out.”

“Workplace violence,” one man replied.

“Too many mass shootings,” said a woman. “They never seem to end.”

To safety consultant Rene Flores, who had traveled from Texas, attending the class felt like a necessity. He thought of El Paso and of Dayton, Ohio, he said, where 22 people were shot to death last month at a Walmart and nine more outside a nightclub, respectively. Days later, seven apparently random people were killed on the streets of Midland and Odessa, Texas, when a gunman hijacked a U.S. Postal Service van and went on a rampage.

At this point, nearly 300 Americans have been slain in mass shootings this year, according to the Gun Violence Archive, a Washington-based nonprofit. The group defines mass shootings as those in which four or more victims are shot or killed.

“Look around,” said Flores, who works with businesses as well as homeless and transitional shelters. “To me, it’s not a matter of if, but when the next shooting will happen. I just want to always be prepared. Always know my options.”

: :

Training programs like ALICE’s are gaining momentum. Last fall, Baltimore County Public Schools, which has 114,000 students and 9,800 teachers, implemented the institute’s methodology.

“If the shooting starts in your room, locking down doesn’t make sense,” said Pete Blair, a criminal justice professor and executive director of the Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training Center at Texas State University.

In such a scenario, he said, it might be more productive to try running away or defending yourself.

“We do not train people to seek out the attacker,” said Blair, whose program says that “if other options don’t work, they should try to defend themselves rather than doing something like playing dead.”

ALICE’s curriculum teaches that while going into lockdown is an option, it might not be enough to survive. In classes, participants practice barricading doors, evacuating and engaging a gunman.

Most active shooters are untrained, according to the firm. During a “violent critical incident,” estimated to last on average five minutes, there are often pockets of time to intervene.

Nester said people near the gunman should try to subdue — “counter” in training lingo — the shooter. Throw books, ram a shopping cart, tackle. But never focus solely on hiding and hoping the killer won’t find you.

“Do something,” Nester said. “You always have options.”

: :

Some analysts disagree.

Ken Trump, a school security expert based in Ohio, calls efforts to flee or counter a gunman “high-risk.”

If K-12 schools urged all students to evacuate, Trump said, their movements could delay police from entering a campus. And barricading doors, he said, can create a lot of noise, thus alerting the gunman to an occupied classroom.

“Traditional lockdowns still work,” said Trump.

Other analysts expressed concern that training can itself have negative psychological effects.

The drills — particularly highly realistic simulations — can traumatize students, said Suffolk University psychology professor David Langer.

“Furthermore, intense fear during active shooter drills may interrupt student and staff learning, making the drills less effective,” said the Boston-based professor.

: :

ALICE contends its techniques work, citing among other examples a 2018 case in which a teacher who had taken its course wrestled to the ground a student who had entered a suburban Indianapolis middle school with two handguns. The teacher was shot but survived, and was able to secure the situation until police arrived.

Having a plan can mean the difference in life or death.

— Andrea Nester, ALICE instructor

In May, an Oregon high school football coach was able to tackle a student who entered a classroom with a shotgun. Everyone at the school survived.

On the other hand, two students died last spring after charging gunmen.

Riley Howell, an undergraduate at UNC-Charlotte, and Kendrick Castillo, a high school student in Highlands Ranch, Colo., were credited with saving dozens of their fellow students’ lives.

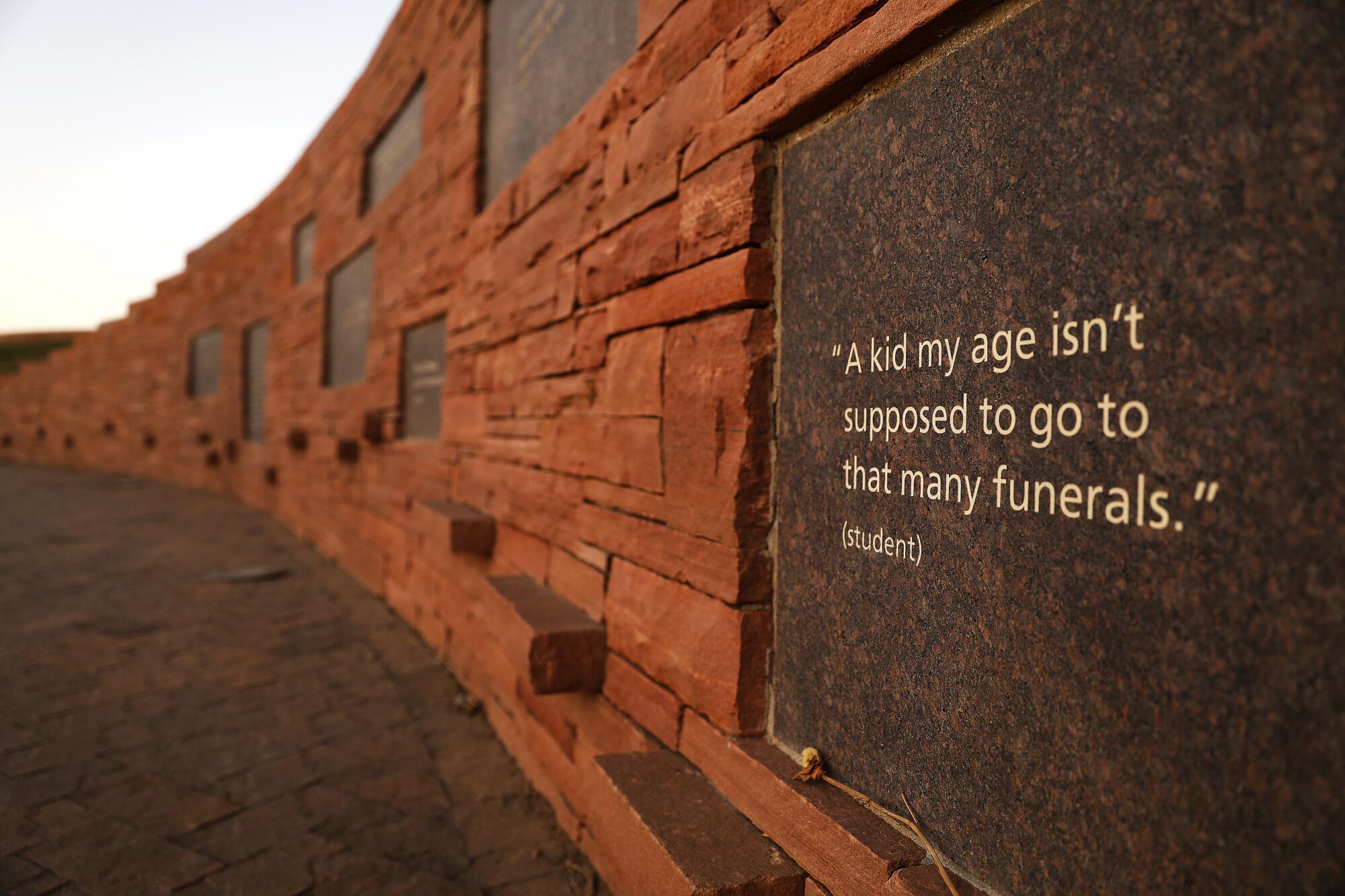

While mass shootings are a nationwide epidemic, perhaps no place in the country is more accustomed to such tragedies than this area along Colorado’s Front Range. More than a decade after Columbine, a gunman entered a side exit of a crowded Aurora, Colo., movie theater and began shooting into the crowd gathered for the premiere of “The Dark Knight Rises.” He killed 12 people and injured 70.

In the Denver metro area, the May shooting at STEM School Highlands Ranch that took the life of Castillo, 18, remains a raw wound.

When a gunman entered his classroom and began firing, Castillo and a pair of classmates lunged at the shooter.

Castillo — a week from graduation — was shot twice and died; more than two dozen other students in the classroom survived.

While Castillo was not trained in counter-techniques, his actions have been lauded by school staff, peers, family and many in law enforcement.

“He’s not a victim; he’s a hero,” said Castillo’s father, John. “He chose to act in that moment — he had no other choice.… He saved lives.

“Sometimes it’s the price a person pays for saving lives. If Kendrick didn’t do something, more people would have died.”

: :

John and his wife, Maria, remember a son who loved robotics and rebuilding computers. With no other relatives in Colorado, the three were particularly close. During summers, they took Kendrick to Florida to see SpaceX launches and visited the campuses of Apple and Google in the Bay Area.

“His eyes would light up on those trips,” John said on a recent afternoon while seated in the family’s living room. Pictures of Kendrick and loving messages from classmates dot the house. Kendrick’s dark green Jeep is still parked in the driveway.

Kendrick had planned to enroll at a local community college this fall and study engineering.

These days, the Castillos spend most evenings at a small cemetery along the Front Range where Kendrick is buried. They watch as the sun sets, slipping over his headstone and behind the foothills.

When grief consumes them, they try to focus on the gift their son gave to the families of the students who survived.

Their son’s legacy loomed large during the Golden training course.

As the two-day session ended, Nester closed, as she often does, with a pep talk of sorts.

“If your life is ever threatened, the last thing you want to do is be passive,” she said.

Many in the classroom sat still, staring intently at the instructor. Some nodded in support. A few had tears in their eyes, thinking about what they would do if confronted by a gunman.

Nester picked up a black dry-erase maker and stood in front of a whiteboard.

“I’m going to write down four heroes, who … saved lives,” she said.

Professor Liviu Librescu, Jake Ryker, Jesse Lewis — those credited with saving lives during mass shootings at Virginia Tech, a high school in Oregon and Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut.

Nester sighed and wrote a final name, one she knew they’d recognize:

Kendrick Castillo.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.