Gold Point, Nev., has a population of 6. One of them runs the inn. Itâs not exactly his calling

GOLD POINT, Nev. â You know those roads out in the middle of nowhere that veer off the main highway and jettison straight out to a pinpoint on the horizon, past bullet-riddled signs and desert buttes?

Well, thatâs where youâll find old Walt Kremin and his little bed-and-breakfast, right where the worn tarmac of State Highway 774 turns to dirt.

For decades, the 73-year-old Bronx-born cowboy has staked his claim in this forgotten mining town, which in the last century has seen its population dwindle from 1,000 to just six, including Kremin.

The place is so lost that the county sheriff rolls through just once a month and locals swear the ghosts of prospectors past sometimes let out eerie heehaws in the dead of night.

Before cellphones arrived, the nearest public call box featured a party line, outside the defunct Cotton Tail brothel some 20 miles down the interstate.

But for some oddball reason, strangers keep showing up to nose around this high-desert outpost 180 miles north of Las Vegas, oohing and aahing at all the mining history and hulks of old vehicles left to bake in the sun, such as the 1916 Dodge flatbed with the suicide doors somebody hauled down from the hills.

Some need a bed for the night and so Kremin, well, he guesses heâll oblige them. Heâll ready up one of a half-dozen old mining shacks heâs converted into comfortable lodging. Pressed hard, he might even cook them a meal.

Kremin, you see, is something of a reluctant innkeeper.

âI donât like making beds,â he says. âI also know that I wouldnât sleep on sheets somebody else slept on. So the beds get made.â

Since his two business partners left him years ago, Kremin has eased around on his cramped-up leg, doing what he can, putting off what he canât.

A lifelong bachelor, he likes being his own boss up here in this hideaway in the hills with its sweeping God-given vistas. Being something of a curmudgeon, he says he doesnât need any woman âwho wants the luxury of a Walmart,â or society at-large poking a nose over his shoulder.

People call Kreminâs rustic operation one of rural Nevadaâs best-kept secrets.

And thatâs the way he wants to keep it.

But to keep the doors swinging, he agreed to a little publicity, knowing that if too many people show up, heâll just tell them to skedaddle.

Still, travelers keep coming â motorcyclists, desert roustabouts, lost families. In an average month, Walt hosts more than 100 guests, a burden that gets him out of bed before first light hits the Lida Valley and flat-topped Jackson Mountain just beyond.

Sometimes, heâll call in help, but stubborn Kremin prefers to handle things alone, declaring, âI donât like to be anybodyâs hall monitor.â

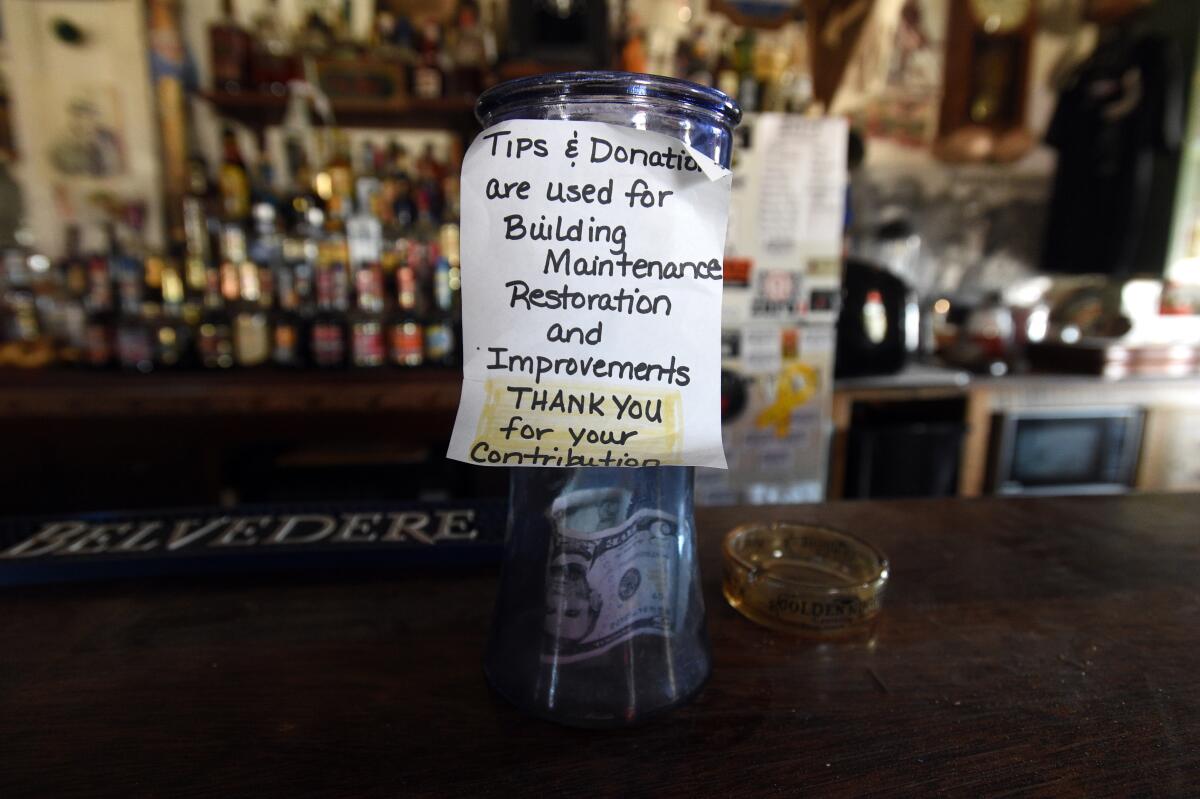

On a recent morning, Kremin tends bar at the saloon he refurbished from the townâs original real estate office. He spent years running around the mountains and antique shops looking for old knickknacks to make it look just right, like an authentic relic of the Old West.

He wears a straw cowboy hat, sky-blue shirt and work boots, a pair of red suspenders barely holding up his bluejeans. And this being rural Nevada, heâs also got his 9-millimeter Smith & Wesson strapped to his hip. Heâs never shot another man, just the pesky bobcats that prey on his domestic cats.

Kremin is known to enjoy a little coffee in his morning whiskey. He pours himself another shot of Usherâs Green Stripe and in his clipped New York accent tells the unlikely story of how he ended up here.

He arrived in Gold Point in 1973, when there werenât many more folks around than there are now. Right off, he fell for the morning fog banks and how the hills glowed pink at dusk.

He soon joined up with his brother, Chuck Kremin, and house painter Herb Robbins, to start buying buildings around the old silver-mining town, which was originally settled in the 1880s and first called Lime Point and then Horn Silver before folks settled on Gold Point.

In 1997, after Robbins won $223,000 on a Vegas slot machine, the partners got to work creating a bed-and-breakfast. But time scatters like the desert dust. Chuck Kremin left because of his diabetes and the fact that his wife was afraid of ghosts. Robbins quit after the pain from a scaffolding accident became too much. He still lives in town.

That leaves Walt Kremin, who knows he canât be everywhere at once, so he rigged up a sensor that trips when visitors arrive, bringing him down in his utility cart to open for business.

âI donât know how to mix drinks,â he says. âIf theyâre complicated, I tell people to make it themselves. Or tell me whatâs in âem, because my memory is terrible.â

But get him going, and Kremin emerges from his shell. Heâll spring up on those wobbly legs for a walk around town, maybe offer a tour of the vintage post office, explaining how the settlers carved a life here 140 years ago.

Deep down, Kreminâs not so irascible after all: âI enjoy people. Thatâs why I donât quit.â

Visitors respond. âItâs well off the beaten path but well worth the trip,â one wrote on Kreminâs website. âHave fun! I always do!â

Another wrote on tripadvisor.com: âWhile we were looking around, up drives a man that opened the bar and told us some great stories. I think his name was Walt. Iâm already making plans to return.â

Added another: âIt took me about a year of hearing âya gotta go to Gold Pointâ before I actually went. Now it is hard to keep me away.â

Kremin only accepts cash, but the nearest ATM is 100 miles away, so guests often leave with a handshake and a promise to send a check. Heâs never been stiffed.

Kremin invites you to come on out, if you must, but warns, âJust donât expect me to leave the light on.â

Glionna is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.