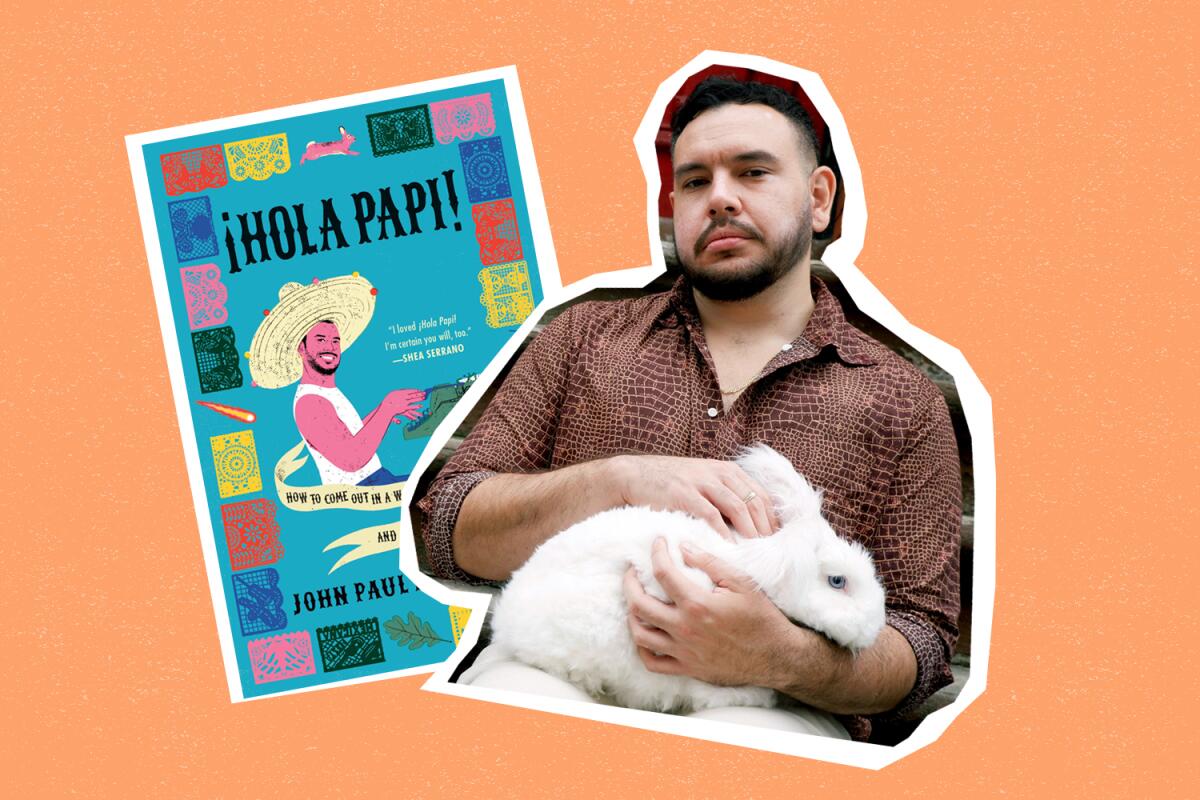

Latinx Files: John Paul Brammer and the making of a ‘Queer Latino Dear Abby’

- Share via

When John Paul Brammer started “Hola Papi!” in 2017 for INTO, a digital magazine launched by gay dating app Grindr, he didn’t think it would get much audience response.

Since then, Brammer’s advice column, which he describes as a “Queer Latino ‘Dear Abby’ huffing poppers” and now lives on Substack, has become required reading for many members of the Latinx and LGBTQ communities — this column in which he responds to a woman afraid that she’ll never find love was one of my favorite reads of 2020. It’s not hard to see why. His writing is incredibly funny, kind and gracious to his readers, and deeply vulnerable in a way that makes it feel as if he’s talking to only you.

“Hola Papi!” has also been adapted into a book, which comes out Tuesday. I spoke with Brammer ahead of its release. This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

You grew up in a biracial household in a small town in Oklahoma. What role did that experience play in your writing?

I think that one of the most formative things about my life was just how uncomfortable I felt in my identity growing up.

There’s a lack of education across America about the history of being nonwhite, marginalized or belonging to any community that has been historically disenfranchised. It’s really hard to find accurate information about those groups. And that’s why we rely so heavily on oral tradition, on telling each other’s stories. There’s so much that you can absorb by simply being part of a community. You are just living in proximity to people who have similar experiences, and if you don’t have that, it can lead to an interesting dynamic in how you see yourself.

I feel like I’m very self-taught in every sense of the word. I’m a self-taught writer, a self-taught artist and a self-taught Mexican. I really wanted to write my perspective without feeling like I’m saying, “Well, here’s what I think being a Mexican American is about!”

All I’m saying is here’s my little piece of the puzzle and I want to write it as richly and honestly as I can.

Something that struck me about your book is how you write about pain and struggle with such humor. To me it made me think, “Oh, this is definitely a Mexican American book.”

I’ve been thinking a lot about why pain and hardship was something that as a kid I thought of as something that could make me real or that could validate me. And I do think that it’s always the case that pain is seen as a bonding agent, as something that can bring a community together. I think that’s why I was so drawn to it as a kid, even though I now see the flaws in that narrative.

I remember when I once met another Mexican and their grandparents looked a little bit like mine but they were rich. I was so stuck on this ubiquitous script where you have your poor abuelos and they are oppressed so they come north, and your family loses its Spanish and other things but your life gets better. I thought that’s how it worked for everyone and that’s just not the case.

But I do believe that sadness paired with happiness is very much part of our culture. Just look at Dia de los Muertos, which is all about death but there are bright colors, smiles and happiness. Mixing the dark with something funny was something my own family did and I think it very much impacted how I tell stories. I remember one time I was walking downstairs to the kitchen and I overheard my abuelos talking about how they couldn’t afford both of their medications. It was tragic, but then my grandma started arguing that her heart was more important than his leg and so that settled it, which made it funny.

Do you think that Latinidad is real?

It is as real as any number of things people believe. It’s real at any given moment, which I know sounds like a cop-out but it’s true. I have more or less given up in trying to determine things like that because I just know there’s no true winning there.

One of the recurring themes from the “Hola Papi!” column and book is an acknowledgment that we are all on a journey of self-acceptance. Do you feel like you’re closer to where you want to be?

I have come to terms with one thing about myself: I am once in a while going to encounter information that is going to shake the idea of what I am, and if I’m not prepared to accommodate that, then I could very easily crumble.

That’s especially true when it comes to my Mexican identity. I know that anything I say right now, if I were to say it with 100% confidence, it would probably end up blowing up in my face. Language changes. Our understanding of identity changes. Race as a construct and as a system is constantly changing to either incorporate or exclude different people at different times. It could very easily be the case, for example, that more Mexican Americans or Chicanos assimilate into whiteness as time goes on. I just can’t rely on this society to legitimize me and to give me an identity that I can very comfortably build a home in, because that’s not how any of this works.

I find it to be similar when it comes to sexuality and for queerness. These debates that we have over what words mean — if we want to use “queer,” or “gay” or “homosexual” — these things change over time and we’re constantly bringing in knowledge and the culture around us is constantly shifting. I very much try never to think that I’ve reached the destination when it comes to identity, because identity is more or less a hallucination. It’s something that we can imagine for ourselves. It can bring us into contact with other people who share similar experiences and we can pool resources in that way. But when we try to define it in a way that’s more of a permanent fixture, then that’s when you’re going to start losing. And I can’t afford to have an identity crisis because I can only write so many books in my life.

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

You’re pretty active on Twitter. What is your relationship with social media?

I can’t deny that the reason I have the career I do is because of Twitter. That’s how I got my very first media job. It’s more or less how I got my second one, too. I do see it as an indispensable tool for moving me along because I was living with my parents in rural Oklahoma, I wanted to be a writer and I needed to get out of there. It’s had a very real material impact on my life.

But it’s tricky squaring that with the fact that it also incentivizes a depersonalization among people. I get so frustrated with it and I see the way people talk to each other. And I’ve noticed the way I’ve talked to other people as well. It’s not like everyone else is doing the wrong thing and I’m doing it right. I would love to tell you that I found a good balance with social media, but I just haven’t. It’s just not the case. I feel like every tweet I make is kind of against my will, or that I capitulated a little bit. I couldn’t keep myself from saying something.

You have worked in media for a few years. What has been your experience being a Mexican American/Latinx in that largely white space?

I’m vocally bitter about a lot of my experiences being a Mexican American in American media, especially during the Trump years.

This sounds bad, but I never had more work in my life. But what I noticed was that oftentimes the things they wanted me to write about, they had subtle ways of informing me what my take should be and what would perform best for them, almost to the point where it felt like they were putting words in my mouth. It’s deeply condescending and it made me pretty resentful. It reveals a lot about what they think the role of any nonwhite or marginalized person in media should be like. We’re not going to trust you to report on the “nuanced, unbiased issues,” but when we do want something biased and bombastic, we want you to yell at someone.

It felt like it was constantly putting me on the offensive, like an attack dog of sorts. What if I have a different, more nuanced approach to this?

How was the pandemic for you and how excited are you for life to somewhat return to normal?

I would love to tell you that I was one of the strongest soldiers in the pandemic, but I wasn’t. I very much put a lot of my life on hold where I was just like, OK, I can’t really do anything right now, so I’m just going to shut down. I’m pretty bad at finding coping mechanisms on the fly.

I’m so excited at the idea of being able to sit in a coffee shop again because I really can’t work from home very well. If I’m writing, I need to be somewhere where there’s like a low hum of productivity around me. That’s where I’m at my best.

I’m very happy the book is being released into a world where there’s more hope than usual.

I wrote this book over two years ago, and now it’s become the center of my life again, which is great because it means people care. But it also means that I can start thinking about working on more projects and using this book as a platform to go even further with the things I want to create. I’m hoping that this summer can be a time of invention and creativity for me.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Cruz Azul did the improbable. They ended the curse.

La Máquina finally did it.

After more than 23 years of heartbreak, Cruz Azul is the Liga MX champion once again. The club, one of Mexico’s oldest, and its fans had seen themselves become the butt of the joke after nearly a quarter of a century of losing in jaw-dropping, spectacular fashion. The team even inspired the verb “cruzazulear” — to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory — which I wrote about in December after yet another epic collapse.

“They have made us suffer so much,” Cesar Ramírez, a 38-year-old accountant from Mexico City, told my colleague Kate Linthicum. “But here we are.”

Following Cruz Azul’s victory, I took to Twitter to invite readers to write about what this victory means for them. Here is what two of them had to say.

Michelle Sanchez, 29, Austin, Texas

On Sunday night, Cruz Azul were crowned champions after 23 years. I was sitting on my couch in tears, in the usual spot my brother and I would sit in to watch soccer games with my dad. Only this time he wasn’t next to me.

Isauro Sánchez Torres — also known as “Richard” or “Richie,” a nickname I gave him — was a longtime La Máquina fan. Unfortunately, I didn’t get to witness and celebrate the end of their long losing streak with him. My dad passed away on Jan. 15, 2021, due to COVID-19 complications. He was 69 years old.

On New Year’s Eve, I received a video from my cousin with a message from former Cruz Azul player Christian “Chaco” Giménez wishing my dad “feliz fiestas” and giving him words of encouragement after he was hospitalized for over two weeks. Because COVID-19 safety protocols were high, he wasn’t allowed any visitors, so seeing him smile for the first time through FaceTime brought hope to my family.

In Mexican Catholic funeral tradition, a cross is lifted nine days after burying someone, symbolizing that one has crossed over to the other side. This championship — the year Cruz Azul won their “novena” title — will be one that we will never forget.

Edgar Perez, 32, Los Angeles

The final whistle was blown, Chuy Corona and Cata Dominguez lifted the cup, and yet it still didn’t seem real. Just six months after the mother of all cruzazuleadas, Cruz Azul finally broke the curse and became the champions of Liga MX. I have been waiting for this moment for so long that I was in shock when it finally happened. I wasn’t even able to cry right away because I couldn’t process everything that was happening.

After getting through the wave of emotion and dealing with the bombardment of texts, I felt as if a great weight was finally lifted off my shoulders. I could only imagine how the players must have felt. What I’m feeling now is a sense of relief. Relief that the trolling and memes are done, for now.

Fernandomania @ 40: How Fernando Valenzuela’s 1981 opening day happened

The latest installment of our multipart documentary series “Fernandomania @ 40” is out today. You can watch here.

The fifth episode takes us to the start of the 1981 season. Fernando Valenzuela was the team’s third starting pitcher, but an injury to Jerry Reuss led manager Tommy Lasorda to tap the unheralded 20-year-old rookie to take his place. El Toro delivered a shutout against the Houston Astros.

More important, the legend of Fernandomania came to life. Missed the first four episodes? You can find them all here.

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.