Green, with a high gloss

What sort of image comes to mind when you hear the phrase âgreen architectureâ?

If youâre like most people, itâs a forgettable one. For nearly all of its history, green architecture has been associated in the public imagination with earnest, uninspired designs that put ecological concerns ahead of aesthetic ones. The result is an architectural affliction critics dubbed âeco-banalityâ: houses with misshapen sod roofs or office buildings with solar panels hidden away behind blandly conventional facades.

The gulf between high-design architects and ecologically minded ones has been, more than anything, a matter of divergent priorities. For their part, the leaders of the green-design movement in the 1980s and most of the 1990s paid little if any attention to the high-design or academic sections of the architecture world. Instead, they were determined to pay most of their attention â and perhaps quite rightly, given who makes the decisions about how and where to build in this country â to persuading lawmakers and corporate America that green design was a mainstream pursuit rather than an eccentric or radical one.

The architects most often celebrated in the design media and popular press, meanwhile, especially academics and self-styled members of the avant-garde, wasted few opportunities to denigrate green design. For them, as writer Susannah Hagan put it, green architecture had âno edge, no buzz, no styleâ; it was not only âpopulated by the self-righteous and the badly dressedâ but âa haven for the untalented, where ethics replace aesthetics and get away with it.â

Peter Eisenman, long a member of the architectural vanguard, had this to say on the subject as late as 2001: âTo talk to me about sustainability is like talking to me about giving birth. Am I against giving birth? No. But would I like to spend my time doing it? Not really. Iâd rather go to a baseball game.â

Happily, though, the distance between the two camps has nearly disappeared over the last few years. Green architects are now paying noticeably more attention to style, understanding that without it theyâll struggle to build a broad reputation in a design world that is increasingly preoccupied with image. Cutting-edge architects are coming around just as quickly, realizing just how much environmental damage the building trades are responsible for â and, more practically, that clients and building codes are demanding energy efficiency in new construction. The list of architects whose firms are now pursuing sustainability in good faith includes Renzo Piano, Norman Foster, Glenn Murcutt and the Swiss duo Herzog & De Meuron, each of whom has won the Pritzker Prize, the fieldâs highest honor.

Perhaps most important, a new generation of young architects has emerged with little patience for the old enmities between environmentalists and designers; for them, the idea of a contradiction between architectural achievement and ecological progress makes little sense. As a result of these shifts, sustainability is being embraced by the same architects who set the fieldâs stylistic and theoretical agendas.

The new traffic between the realm of green and cutting-edge architecture is particularly notable, and particularly busy these days, in residential design. Since houses are small and self-contained, and often funded by progressive private clients instead of bottom-line-oriented commercial ones, they offer an ideal testing ground for new green strategies.

The most remarkable aspect of sustainable residential design these days is its diversity: of size, type, style and location. Green houses now rise from tightly packed city streets as well as hillsides and rocky seashores. They are single-family dwellings and subsidized apartments, primary residences and weekend getaways. They are sheathed in glass, in bamboo, in synthetic panels made from recycled newspaper. They take their aesthetic cues from primitive dwellings, from organic forms and, significantly, from architectural predecessors who include the founders of the Bauhaus as surely as Thomas Jefferson, Paolo Soleri or Frank Lloyd Wright.

Indeed, itâs becoming impossible to ignore how many green houses are being designed in the sleek, ornament-free style that has once again become the prevailing approach among high-end architects, particularly younger ones in America and Europe.

Not surprisingly, Southern California, long home to the architectural cutting edge, especially in residential design, is helping to redefine sustainable design to new heights. Three recent projects in particular suggest the new aesthetic variety, and the new ambition, of green residential architecture.

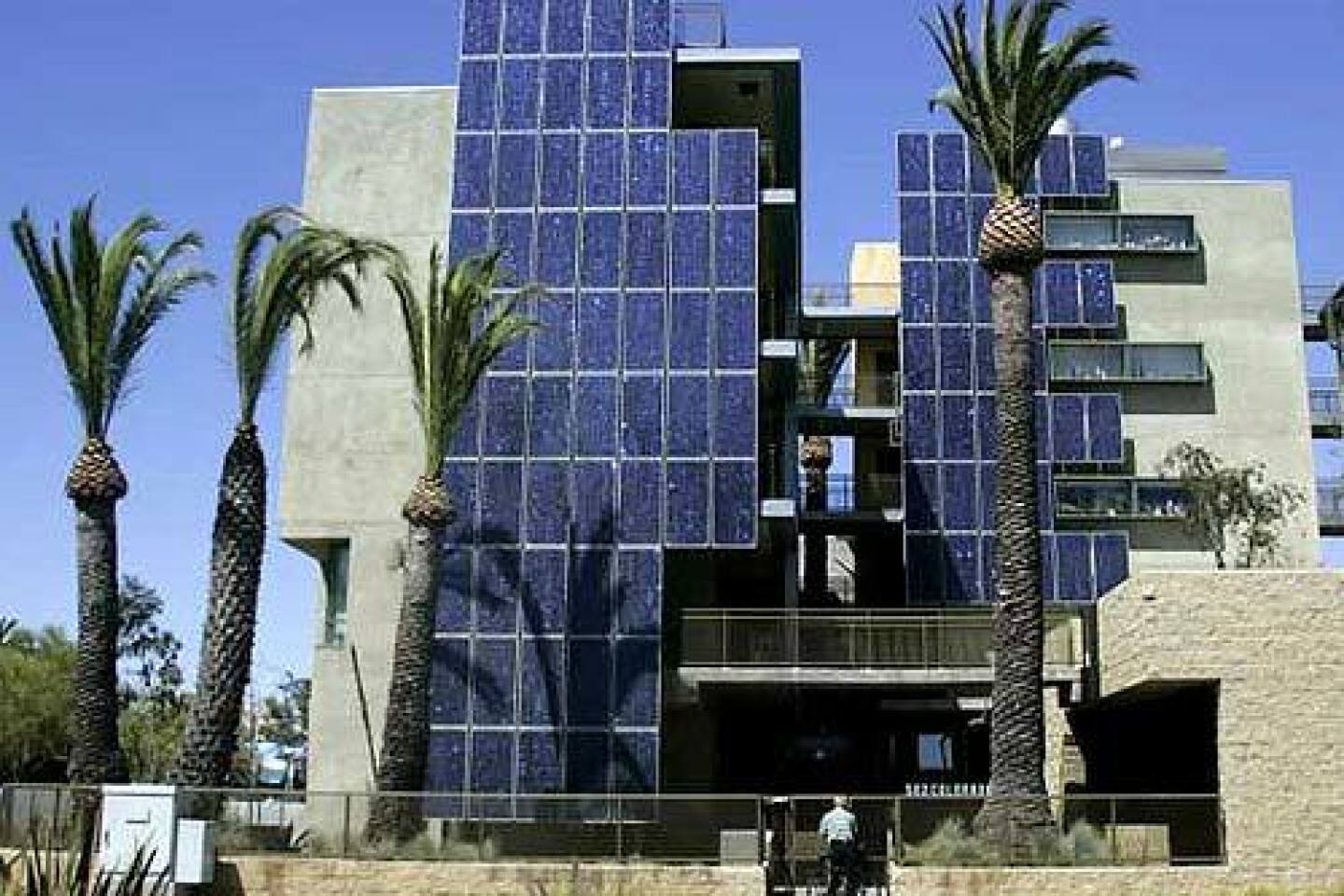

The largest and most prominent of the three stands near the beach in Santa Monica, its grid of 199 bright blue solar panels glinting in the sun. Colorado Court, a five-story, 44-unit apartment complex that welcomed its first tenants in early 2003, is the first large residential complex in the United States to combine advanced sustainability with low-income housing.

Designed by the Santa Monica firm Pugh + Scarpa, Colorado Court produces enough energy to satisfy 92% of its power needs. And it includes a list of sustainable features as long as any building in America, from age-old gestures like natural ventilation to recycled materials to keeping its tenants within walking or biking distance of their jobs and shopping.

The buildingâs single-residency studio apartments, though small at 300 to 375 square feet, are a bargain by Santa Monica standards, renting for less than $400 a month. Pugh + Scarpa partner Angela Brooks suggests that low-income tenants are precisely the kind of residents whom green architecture ought to be serving â particularly in California, where the utility markets have been prone to huge price upswings in recent years.

âThis group of people is the least able to pay for things like water and power,â she says. âWhen utility bills go up, it hurts them much more than others.â

From the beginning, it was important to the architects, who work squarely in the Modernist vein, that the building have some architectural panache. In plan, Colorado Court is made of three arms â two long ones on the outside and a shorter one in the center â that reach out to catch the prevailing ocean winds. In elevation, it has a precise, squared-off look, with outdoor hallways connecting the units on each floor. The deep-blue solar panels, made up of 5-inch square receptors, make the building immediately recognizable even from a distance of several hundred yards away. Inside, natural light, breezes and 10-foot ceilings help the units feel open to the outside and less cramped than their square footage might suggest.

Venice architect David Hertz, best known for pioneering the use of a âgreenâ concrete called Syndecrete, hasnât built residential projects at the scale of Colorado Court, but his work has been no less important in suggesting that handsome design and sustainability can be comfortably combined.

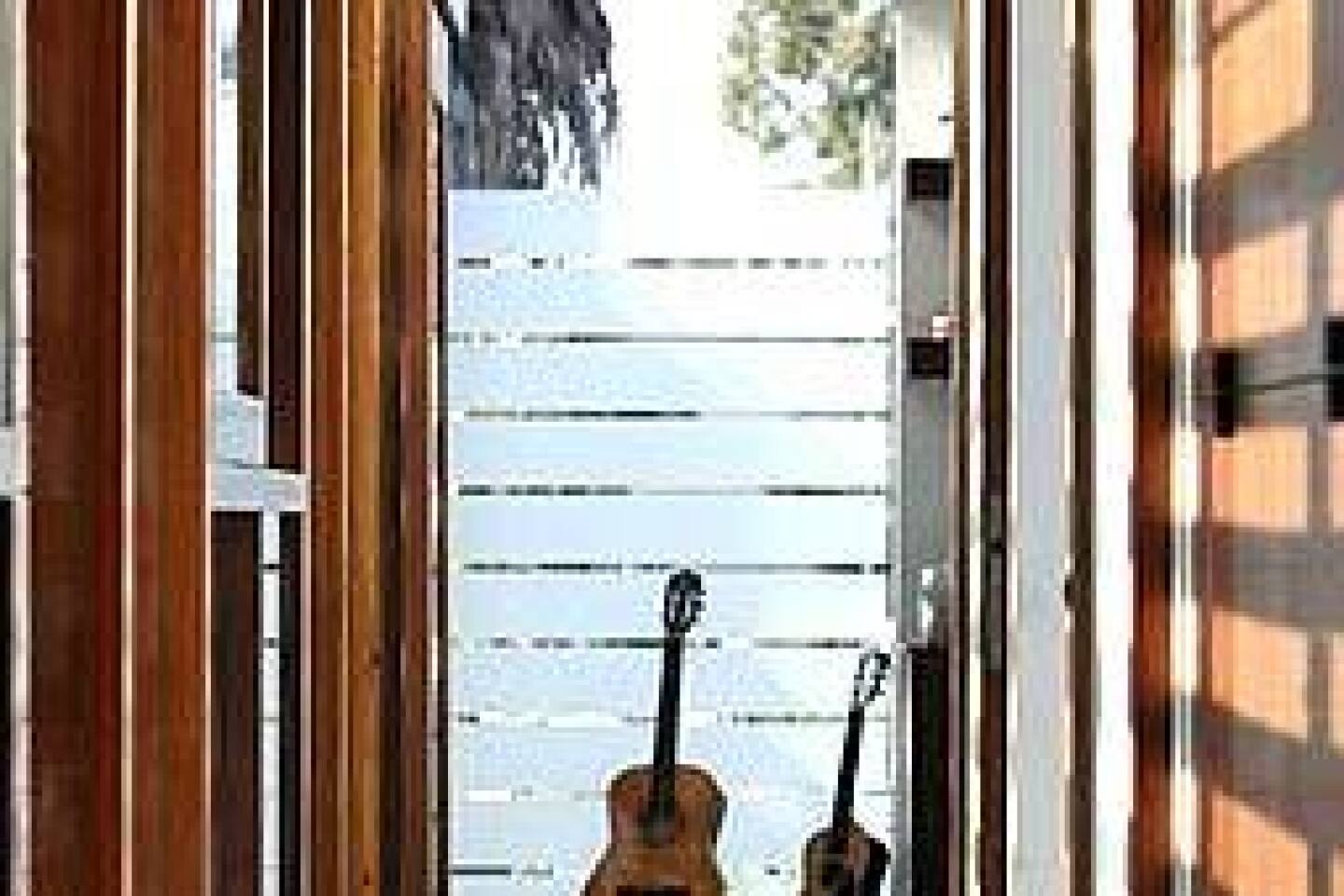

A perfect case in point is Hertzâs recent addition to his own familyâs house in Venice, which enlarged it from 2,500 to about 4,400 square feet. Inspired by Indonesian architecture, it is executed in a style that might be called Balinese Modern, with mahogany wood stairs, trellises and other elements complementing exterior walls of concrete. As a staunch proponent of green design, Hertz thought the mere fact of adding that much space, however much his wife and children seemed to need it, troubling. âThereâs no getting around the fact that on a purely ecological level 4,400 square feet is a lot of house by most of the worldâs standards,â he says.His solution was to try to make the house the greenest house of its size heâd ever seen. âI employ green techniques in all my work,â he says, âbut Iâve thought of my own house â both the original and now this addition â as a kind of case study, even a working laboratory, for me to live with environmental systems, materials and methodologies.â

An array of 20 solar panels on the roof help generate about 70% of the homeâs electricity needs, and other sections of the roof are given over to flat-plate collectors that provide hot water to the water heater, which then sends it into a radiant heating system in the concrete floors. Additional hot water is provided by vacuum tubing on the roof, which uses a parabolic collector to focus the sunâs rays.

All the wood used in the house has been sustainably harvested, and much of the concrete is Hertzâs own Syndecrete, which contains about 41% recycled content and is twice as light, with twice the compressive strength, of normal concrete.

The material acts as a kind of âsolar sinkâ inside the house for passive solar energy transfer, storing up the sunâs warmth during the day, and thus keeping it from overheating the interior, and then slowly releasing that heat during the night.

Hertz hopes that by using Syndecrete in architecturally sophisticated projects he can help speed the adoption of recycled and environmentally friendly products to what he calls âa high-end, design-oriented market segmentâ that in the past has turned up its nose at green architecture.

Hertzâs house, a stoneâs throw from the beach, features some built-in natural amenities, such as cooling breezes that blow in from the ocean and reduce the need for air conditioning.

For a green house in a gritty corner of northeast downtown Los Angeles, Jennifer Siegal essentially had to import nature. Siegal, who runs a Venice-based firm called Office of Mobile Design, was hired by developer Richard Carlson to design a house across the street from one of his projects, the Brewery Lofts. It was Siegalâs first full-scale residential project.

The lot Carlson had earmarked for his new house was little more than a storage yard for scrap metal and other materials and bounded on one edge by the rear wall of a factory. Carlson enclosed the other sides of the property with a 12-foot-high wall made of rusting steel slabs. He told Siegal he wanted to build the new house largely using the old metal shipping containers, 40 feet long and 9 feet high, that heâd been storing on the site. It hardly seemed a recipe for architectural success.

Siegal began with a simple design gesture, stacking two containers on each side of the lot and then connecting them with a slanting roof and floor-to-ceiling expanses of glass. One stack of containers holds the master bedroom above and a library and media center below; the other contains Carlsonâs office up top and a laundry room and bath at ground level. Between the two pairs of containers is a living room with a flagstone waterfall and a kitchen to the rear.

Along with the containers, many of the other materials Siegal used were recycled or salvaged, including the huge Douglas fir beams in the living room ceiling, which came from a construction site nearby. Outside, the house is nearly enveloped by an extensive garden. Designed by James Stone, it features wandering paths, flowers and plants of all kinds, and an 85-foot-long stream.

The result is not only a surprisingly lush urban oasis but a spare, assured piece of architecture â and something of an essay on the hidden beauty of salvaged industrial materials. In that sense, the design by Siegal makes a fitting icon for a new approach to sustainable architecture, for projects that are environmentally resourceful and highly efficient but also aesthetically striking.

âEverything was here already,â Carlson says. âWhat Jennifer and I did was figure out a way to lean it all together.â

Excerpted from âThe Green House:

New Directions in Sustainable Architectureâ by Alanna Stang and Christopher Hawthorne (Princeton Architectural Press, 2005). Alanna Stang is editor of the forthcoming magazine Cookie from Fairchild Publications. Christopher Hawthorne is The Timesâ architecture critic.

*(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

*

Green checklist

By Alanna Stang and Christopher Hawthorne

*

There is no perfect universal definition of what makes a house green, but a good place to start is this straightforward suggestion from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation: âAny building that has significantly lower environmental impacts than traditional buildings.â

Beyond that, the key, most experts in the field agree, is a flexible and holistic approach, trying to make environmentally friendly decisions at every point in the residential planning, design and construction process â while keeping in mind that there are always going to be tough, even seemingly impossible, choices to be made. An architect or homeowner deciding between a kind of roofing material that is wasteful to produce but available locally and an eco-friendly variety that has to be trucked in from 2,500 miles away will not be helped by a one-size-fits-all checklist.

In general, though, there are steady guidelines and priorities. A residential design that aims for authentic greenness should be as small as possible, for a house that uses every sustainable technique under the sun will not be as kind to the earth as any house half its size. It should be oriented on its site to take advantage of winter sun and summer shade and minimize damage to the plants, animals and soil already there. And it should be located as close as realistically possible to public transportation, workplaces, schools and shopping areas.

None of those basics need add any cost to the construction of a new home (save for the potential higher prices of a piece of land near or in a city). Indeed, following the first size rule will necessarily lead to lower building costs.

Beyond that, greenness is generally a question of two issues â energy efficiency and the eco-friendliness of its materials â along with a broader sense of how a new house or apartment building ties into its local, regional and global context. Often, these concerns are intertwined, but in general architects committed to sustainability will rely on the following:

Recycled materials and even existing foundations or building shells.

Wood from stocks that are sustainably managed.

Materials low in embodied energy â that is, the energy required to extract and produce them and bring them to a building site.

Natural materials, such as bamboo, that are easily regrown or replenished.

Efficient lighting systems that take advantage of or redirect daylight to reduce the need for electricity, or include sensors and timers to shut off lights when not in use.

Water systems that collect rainwater or treat so-called gray water (from sinks and showers) so that it can be reused for gardens or toilets.

Strategies to ensure that a house will have a long life, because it is architecturally significant, comfortable, or adaptable to future uses.

Insulation, glass and facades that are energy-efficient or that promote air circulation by natural ventilation instead of air conditioning.

Strategies to take advantage of the sunâs rays, either passively, by storing sunlight as heat, or actively, using solar panels to convert light into electricity.

Interior materials and finishes, from carpets to paints, that minimize unhealthy chemical emissions and promote a high level of air quality.

The point is not to meet some standard of perfection but to make careful, informed choices, from selecting a building site to picking out the appliances, cabinetry and plants for the backyard.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

Weâll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.