What is CrowdStrike, and how did it cripple so many computers?

- Share via

Talk about irony: The software that paralyzed Windows computers around the world late Thursday night and early Friday morning was planted by a company that protects Windows computers against malware.

That company is CrowdStrike, a publicly traded cybersecurity firm based in Austin, Texas. It acknowledged the problem around 11 p.m. Thursday and started working on a solution, offering a work-around in the wee hours Friday and a fix a few hours later.

The vast sea of “blue screens of death” triggered by CrowdStrike’s error is a testament to the market-leading status of the company’s software, which detects and defends against malicious code planted by hackers. Its approach is known as “endpoint security” because it installs its defenses on devices that connect to the internet, such as computers and smartphones.

According to the website 6sense.com, CrowdStrike has more than 3,500 customers, which represent about 1 out of 4 companies buying endpoint security. Although most of its customers are based in the United States, it has hundreds in India, Europe and Australia, 6sense reports.

Here’s a quick explanation for how things went wrong so quickly for so many Windows users around the world, including airlines, hospitals, banks and government agencies.

The software issue was part of an update from cybersecurity company CrowdStrike, which protects computers for many of the biggest companies in the world.

The Falcon Sensor update

One of the selling points of CrowdStrike service is that it can improve its defenses rapidly as new threats are discovered. As part of that service, it continuously and automatically updates the Falcon Sensor software on its customers’ machines.

Automatic updates are, under normal circumstances, a good cybersecurity practice because they prevent clients from having machines with outdated defenses on their networks. But the latest incident reveals the flip side of the coin.

According to CrowdStrike, the problem was triggered by a “single content update” for its customers with Windows PCs. The buggy code wasn’t detected until after it had been downloaded and installed on many of CrowdStrike’s clients’ machines.

Once loaded, the bad update interfered with core functions of the PC, causing Microsoft’s infamous blue error screen to pop up and convey a message along the lines of, “Your PC ran into a problem and needs to restart.” And as long as the update remained in place, restarting the machine led to the same errant result.

The fix offered by CrowdStrike

CrowdStrike stopped sending out the faulty update early Friday morning, so machines that had not loaded it yet were spared the turmoil.

For machines caught in the cycle of blue-screen hell, the company initially offered step-by-step instructions for how to reboot Windows in a mode that would allow them to find and delete the buggy update. The drawback, as many commenters online noted, is that this machine-by-machine approach isn’t much help for organizations with hundreds or thousands of bricked PCs.

Behind a massive IT failure that grounded flights, upended markets and disrupted corporations around the world is one cybersecurity company: CrowdStrike Holdings Inc.

According to the tech website 404, Microsoft also suggested that rebooting a crashed machine multiple times — as many as 15 — could solve the problem.

Within a few hours, CrowdStrike was distributing a piece of software that removed the buggy code. This worked only for customers whose machines were able to connect to the internet and download the fix, though; everyone else would be left with the PC-by-PC work-around.

Scammers jump in

CrowdStrike Chief Executive George Kurtz issued an apology late Friday morning, promising that the company would “provide full transparency on how this occurred and steps we’re taking to prevent anything like this from happening again.” He also warned that bad actors online would try to take advantage of the incident, urging customers to be on the lookout and “ensure that you’re engaging with official CrowdStrike representatives.”

Sure enough, the company announced two hours later that it had found numerous instances of scammers trying to lure victims by posing as CrowdStrike technical support in emails or phone calls. Others were “posing as independent researchers, claiming to have evidence the technical issue is linked to a cyberattack and offering remediation insights.” And yet more were making bogus offers to sell software to fix the problem, the company said.

CrowdStrike identified at least 30 malicious websites that were involved in these cons.

Researchers at the internet security company Norton also warned about the emergence of fake domains and impersonation scams tied to the incident.

“Scammers can leverage social ads, emails and text messages to drive people to the bogus sites,” Norton warned. “These sites look legitimate and aim to extort personal or financial information, preying on the fear and doubt people may have related to the incident. Moreso, many times, fake domains have high search rankings, which can make them appear more credible.”

In an impersonation scam, con artists may send messages mimicking CrowdStrike’s branding to potential victims, claiming that they have been affected by the incident. The messages direct people to a fraudulent customer support line or web page, with a goal of stealing money or sensitive personal information, Norton said.

“This should serve as a cautionary tale, reminding people worldwide to remain extra vigilant as scammers use every angle and method to exploit them,” Luis Corrons, a Norton security evangelist, said in a statement.

The lessons from the CrowdStrike debacle

Some Macintosh and Linux users, who were immune to the CrowdStrike-induced upheaval, devoted a portion of their morning Friday to spiking the football on Windows, even though the problem wasn’t caused by Microsoft.

Other observers argued that the incident demonstrated the risk of having one potential point of failure affecting millions of computers — a problem that has been demonstrated repeatedly during the broadband era.

Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg made a similar point at a news conference Friday in East Los Angeles. “A lot of people around the country and around the world are shocked to discover that a single issue with a single piece of software can have that many knock-on implications. So ... that’ll be a question that really goes to the design of our systems for the long term,” Buttigieg said.

“As a recovering computer science major,” Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Torrance) said on X, “I’m not surprised a faulty update by CrowdStrike took down Microsoft Windows. Always risks in giving another software program full or near full access to an operating system.”

For the record:

12:26 p.m. July 19, 2024An earlier version of this story reported that Steve Garrison was founder of Stellar Cyber in San Francisco. He is one of the founders, and the company is based in San Jose.

Steve Garrison, one of the founders of Stellar Cyber in San Jose, said it’s more important to figure out how to make improvements than to play the blame game. This incident, he said, underscores the need for companies to spend plenty of time checking the quality of their products in a controlled environment before releasing them to customers.

Another lesson, he said, is the need for companies, their competitors and their customers to work together as a community to spot problems. “What do we need to do to check the checkers of our supply chain?” he asked.

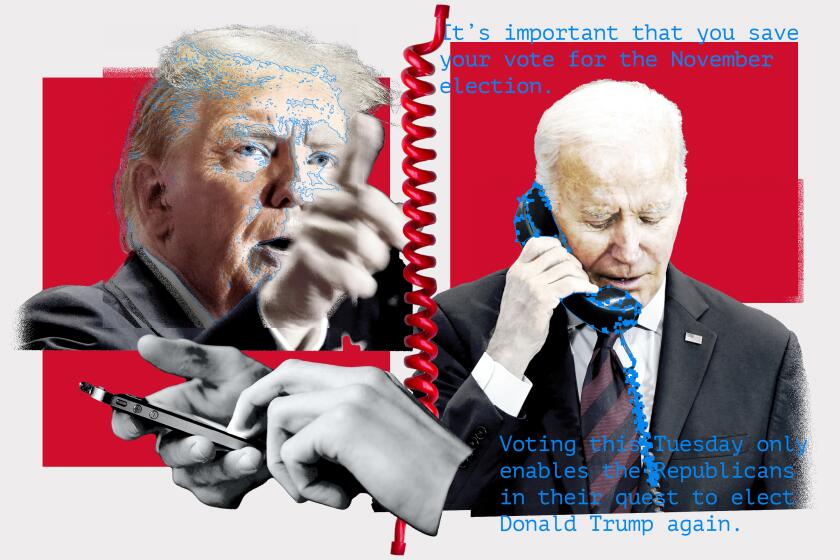

AI is bending reality into a video game world of deepfakes to sow confusion and chaos during the 2024 election. Disinformation is a danger, especially in swing states.

Dan O’Dowd, a developer of security software for the military, said the fiasco demonstrates that we need better software in critical systems.

“The immense body of software developed using Silicon Valley’s ‘move fast and break things’ culture means that the software our lives depend on is riddled with defects and vulnerabilities,” O’Dowd said in a statement. “Defects in this software can result in a mass failure event even more serious than the one we have seen today.”

He added, “We must convince the CEOs and Boards of Directors of the companies that build the systems our lives depend on to rewrite their software so that it never fails and can’t be hacked. ... These companies will not take cybersecurity seriously until the public demands it. And we must demand it now, before a major disaster strikes.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.