- Share via

The doubts have resurfaced, the same old chatter as before, swirling around DeShaun Foster like an all-out blitz.

He’s never been a coordinator, much less a coach. What does he know about leading a team? Isn’t he way too mellow and reserved for this?

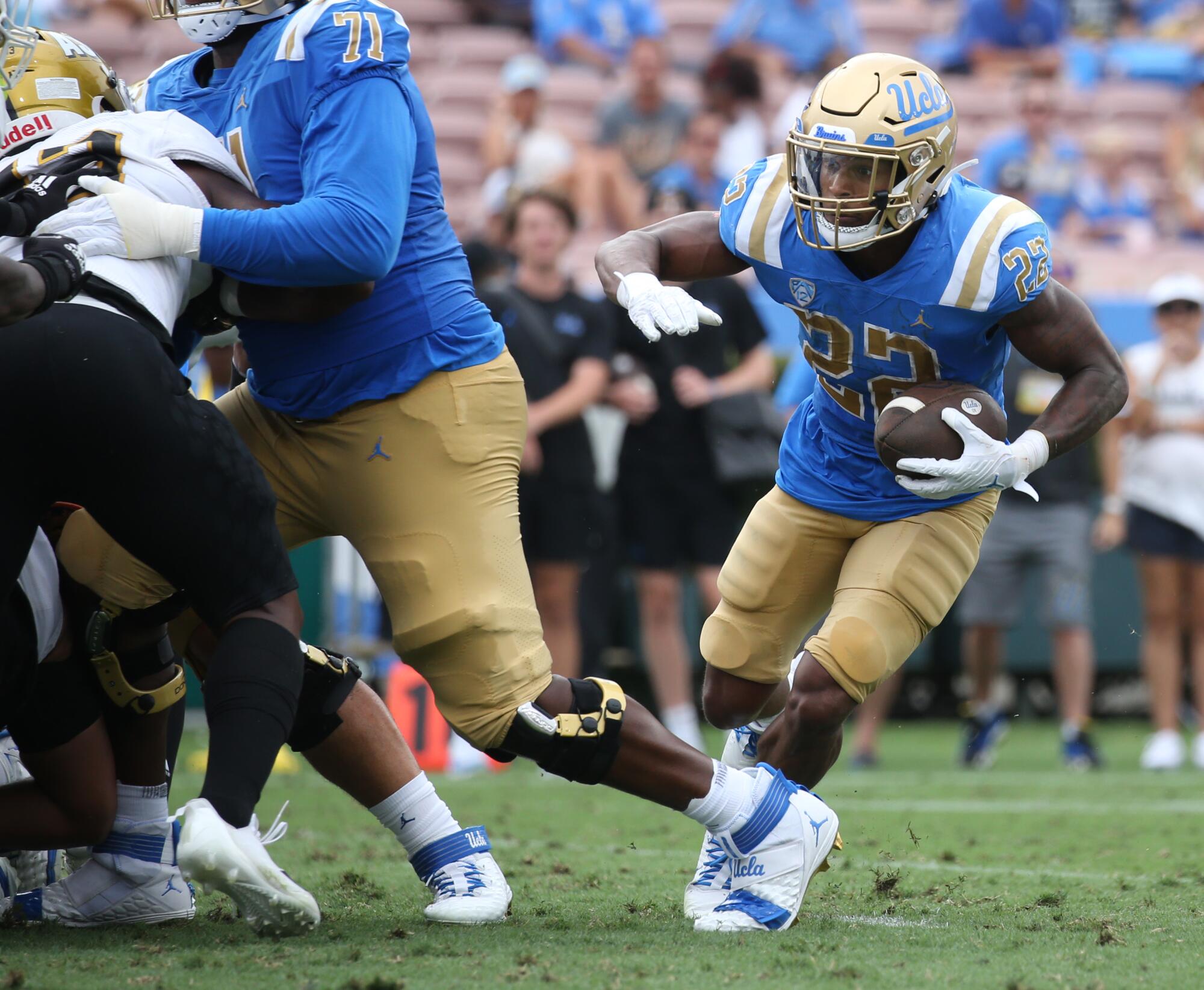

Some of the skepticism that greeted UCLA’s new football coach upon his hiring in February subsided during a feel-good offseason. Foster salvaged recruiting, galvanized his team and energized fans over four blissful months.

Then came Foster’s freeze during Big Ten media day. The coach went quiet after about a minute of small talk on the big stage, his silence broken only by an uncomfortable smile. One of the few things he did say — “We’re in L.A.” — became an instant meme. It was all the radio hosts and podcasters needed to turn back on the spigot of suspicion.

See, this guy doesn’t know what he’s doing. He’s unprepared. If he can’t speak to the media, how is he going to deal with his players?

Whenever his verbal stumble is brought up, Foster’s expression remains unchanged, as if he’s wearing earplugs. He’s quick to remind you that he played this game at the highest levels, reaching the Rose Bowl with the Bruins and the Super Bowl with the Carolina Panthers, before going on to develop a fleet of NFL running backs at his alma mater.

As far as he’s concerned, he has a master’s degree in football. Among the many lessons he’s learned is that smooth talking doesn’t win games.

“I’m just not a rah-rah guy, you know?” he said. “You don’t get any points for being rah-rah.”

Besides, he’s already outrun far bigger challenges than a speaking slipup. Take the 18 defenders who stood between him and the goal line in practices at Tustin High. Or the two running backs in front of him on the UCLA depth chart. Or the half-dozen Philadelphia Eagles who tried to bring him down on one of his most famous NFL carries.

None stood a chance against the slippery speedster who might use a spin move or a stiff-arm to free himself. Once again, embarking on this deeply personal quest, Foster has every intention of breaking through.

Having played for UCLA when the team won a school-record 20 consecutive games in the late 1990s, capping a streak of eight consecutive victories over rival USC, Foster knows what it’s like to win over a city as large as Los Angeles. That’s what he’s after, not winning any press conferences.

“You want to get it right back,” he said, “to just so we can walk around campus with our chest out a little bit.”

It’s almost the midpoint of spring practice, a time when energy can dip and players can drag.

Not on this warm April morning. The entire team gathers in the middle of the field, players unleashing a hearty roar in anticipation of what’s to come.

As two lines flank an open space for one-on-one competitions, Dr. Dre’s “Still D.R.E.” pulsates over nearby loudspeakers.

Though I’ve grown a lot, can’t keep it home a lot

‘Cause when I frequent the spots that I’m known to rock

You hear the bass from the truck when I’m on the block

The competitions are Foster’s idea to jump-start each practice, like a caffeine jolt before the humdrum rhythms take hold. Football is supposed to be fun, right?

On this day, a flurry of plays match a defensive back against a receiver. Finally, after Jaylin Davies shadows Rico Flores Jr. on an overthrown pass that falls incomplete to mark the end of the competition, other defensive players run over to swarm Davies in celebration.

Foster was familiar with that sort of sensation. Two months earlier, after being cagey with players asking what he knew about UCLA’s coaching search, Foster stood and waited for his cue in a second-floor hallway of the Wasserman Football Center. Inside the adjacent auditorium, athletic director Martin Jarmond prepared to introduce his biggest hire in nearly four years on the job.

“We want somebody that wants to be a Bruin,” Jarmond told the players seated in front of him. “Well, we didn’t get somebody that wants to be a Bruin. We got a Bruin. Come on out, coach.”

As Foster strolled into the room in a black satin bomber jacket with UCLA stitched in blue across the front, players leapt from their seats to mob him amid a din of cheering and clapping. They had gotten their guy.

It was something of a surprise selection. Foster didn’t appear on many media candidate lists after predecessor Chip Kelly departed to become the offensive coordinator at Ohio State. Part of the reason was that earlier that week, Foster left his job as UCLA’s running backs coach to take the same position with the Las Vegas Raiders.

There was also that résumé that was a little light in the relevant experience section. Volunteer assistant. Graduate assistant. Director of player development and high school relations. Running backs coach. To many, it didn’t seem like the credentials of someone on the verge of becoming a Big Ten coach.

During a whirlwind search lasting less than three days, Jarmond initially targeted candidates with coaching experience before zeroing in on Foster. The more they talked, the more Jarmond became enchanted with Foster’s vision for restoring excitement around the program based on his pillars of discipline, respect and enthusiasm.

His players were immediately sold. Only a few transferred out and a potential star returned. One of Foster’s first calls upon getting the job was to running back Keegan Jones, who was set to transfer to play for former UCLA coach Jim Mora at Connecticut but instead ran a reverse back to Westwood.

“He called and said, ‘Listen, I love this guy, I want to play for him,’ ” Mora said of Jones. “Which I thought was awesome. To me, it said a lot about the way not just one player, but I would assume all the players feel about DeShaun.”

Perhaps more than anyone, Mora understood the allure of UCLA’s new coach. He had given Foster his start in coaching as a volunteer assistant with the Bruins in 2013, followed by a rapid series of promotions.

“For me, it was, OK, how do I get this guy into a position where he can most affect our players on a year-to-year basis?” Mora said.

Four years later, after Foster had spent one season as Texas Tech’s running backs coach, Mora engineered a surprise return. When a recruit that UCLA was pursuing asked Mora who his running backs coach would be at a time when the Bruins had an opening at the position, Mora unflinchingly told him “DeShaun Foster.”

Having heard the exchange, UCLA linebackers coach Scott White called Foster to tell him that he was going to get the job. Sure enough, Mora called a few hours later and made his pitch.

“He was like, ‘You want to come home?’ ” Foster recalled, “and I said, ‘Yep.’ ”

Mora quickly saw how Foster’s strong feel for the fundamentals of the position rooted in his own playing experience made him a winning hire, even if he did express himself at barely above a whisper.

“People have to lean in to listen to him and hear him,” Mora said, “but the way he presents himself, people gravitate toward him and they trust him and that’s such a big thing.”

In Foster’s first season, the Bruins ran for 113.4 yards per game with the same group of running backs who had produced only 84.3 yards the previous year. After Kelly replaced Mora before the 2018 season, UCLA’s running backs became the team’s best and most consistent position.

Foster developed a slew of players who went on to the NFL, including Zach Charbonnet, Josh Kelley, Demetric Felton Jr., Brittain Brown and Carson Steele. With the exception of Charbonnet, a highly coveted transfer from Michigan, it wasn’t exactly a four- and five-star bunch. Kelley arrived as a walk-on from UC Davis, Felton was a converted wide receiver and Steele had transferred from Ball State.

Foster nurtured them all with the belief they could do great things. Most of them did, Kelley running for a rivalry-record 289 yards and two touchdowns during a victory over USC in 2018.

“That was a moment where it was like, dang, he took a chance on me as a walk-on,” Kelley said of Foster, “and he vouched for me, he was like, yeah, I think this guy can play.”

Foster knew what it took to break the Trojans’ hearts, having done it himself all those years earlier.

As the story goes, the young boy, maybe 5 or 6 years old at the time, sat on his father’s lap watching Houston Oilers running back Earl Campbell break one tackle after another on television before making an announcement.

“Dad, I can do that,” Foster said.

It was a promise fulfilled on playgrounds and football fields throughout his hometown. As a sixth-grader at Columbus Tustin Middle School, Jennifer Brough (nee Flint) had the incredible fortune of playing quarterback on Foster’s flag football team when he was an emerging star in eighth grade.

“I’m sure I just handed the ball off to him,” Brough said with a laugh some 30 years later.

Can Lincoln Riley cool down his already hot coaching seat? Can UCLA’s DeShaun Foster coach the team to a winning record?

What struck Brough most about Foster as she followed him to Tustin High and UCLA was that his demeanor never changed no matter how much his profile rose.

“He was always very unassuming, bordering on shy,” Brough said. “He was never in-your-face anything. He’s very similar to how he is now — quiet but kind of there to get the job done.”

It was an approach taught by parents Cheryl and Albert, whose pillars were humility, service and respect. DeShaun exhibited them all as a can-do freshman who played four sports at Tustin High, dropping baseball after one season to focus on track, basketball and football.

His running style — smooth, quick and powerful — evoked comparisons to NFL greats Eric Dickerson and Marcus Allen, even if Foster fancied himself as being in the mold of seven-time Pro Bowler Marshall Faulk.

“Bullyball,” Foster said when asked to describe the way he ran.

Foster wore Faulk’s No. 28 until the number no longer was available in high school, switching to No. 26. By then he was practically unstoppable, even when the fight wasn’t fair.

During one practice drill, his coach would stack the defense with as many as 18 players and give them the play call — usually “36 Bench,” a pitch to Foster off right tackle that was a staple of his offense — before the snap.

“I told DeShaun, ‘I don’t care who’s there waiting for you, there’s three yards — you get me three yards,’ ” said Myron Miller, Tustin’s former longtime coach. “And he did.”

Eventually growing to 6 feet and a sturdy 205 pounds, Foster seemed invincible, fortifying himself with what Miller described as the “Tustin steroid” — bags of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches the coach brought to campus and ordered players to eat. Foster would grab two before class and two more during lunch or after practices spanning four hours. He ingested so many of those sandwiches that he can’t stand the taste of peanut better today.

Sometimes it seemed as if the only thing that could stop Foster was late-game fatigue from playing safety in addition to running back. Whenever he played defense, opposing teams forced him to chase wide receivers running deep decoy routes, knowing all that sprinting eventually would tire him out. Miller felt he had no choice but to make his star play both ways given a roster with only 20-something players.

“DeShaun at 70% was better than anybody else I had,” Miller said, “so I never thought about it.”

Well, maybe once. Late in an epic division championship game against Santa Margarita and USC-bound quarterback Carson Palmer, Foster pulled up with cramps on one long run, unable to complete a sure touchdown. He finished the game with 378 yards rushing and six touchdowns but walked through the handshake line in tears because of the only number that mattered — his team’s 55-42 defeat.

“It’s really hard to see,” Miller said, “because I know how much he put into it.”

On signing day, the player who had piled up an Orange County season-record 3,398 rushing yards to go with 59 touchdowns showed up at school undecided about his college choice, still torn between UCLA and Texas. (USC had fallen out of the running after making the mistake of recruiting him as a defensive back.)

By the end of first period, Foster had made up his mind, swayed by assurances that he could play running back while staying close to home. He would become a Bruin, sparking a wild celebration on campus when his letter of intent arrived.

“It didn’t matter which floor of the athletic department you were on,” said Bobby Field, the UCLA defensive backs coach who oversaw the team’s Orange County recruiting efforts, “you heard the cheer go up when that fax came in, I can assure you.”

Long before his excruciating pause at Big Ten media day, Foster suffered from performance anxiety. He recalled an elementary school teacher once dragging him out of the bathroom to give a speech about Martin Luther King Jr.

In high school, Foster told reporters he was nervous before his first carry and before taking over as the featured back. On the eve of his college debut, against Texas, Foster acknowledged significant jitters even though he was listed behind Jermaine Lewis and Keith Brown on the depth chart.

“I know for a fact,” Foster wrote in a diary for the Orange County Register, “I’ll probably be about to faint.”

On game day he managed to stay upright, rushing for 44 yards and his first touchdown. It wasn’t long before he earned more carries than his older counterparts even though he didn’t start one game that 1998 season.

“We just couldn’t keep him off the field,” said Kelly Skipper, the team’s running backs coach.

Foster’s big breakthrough came in the rivalry game, the young back shaking off strep throat to swallow USC whole. He became the first true freshman in school history to score four touchdowns in a game — three coming on runs and another on a catch — while finishing with 109 yards rushing during the Bruins’ 34-17 victory over the team that wanted him to play defensive back.

“I mean, it’s like Michael Jordan’s flu game, right?” said Kris Farris, the Bruins’ All-America left tackle that season.

A high ankle sprain as a sophomore and a broken hand as a junior, even as he piled up yards when healthy, prompted Foster to return for his senior year. He pictured himself in a snazzy suit at the Heisman Trophy ceremony, rising from a table with his family to accept the award.

It seemed like more than a daydream when UCLA beat Alabama and Ohio State on the way to a 6-2 start. Foster emerged as the Heisman front-runner after logging six 100-yard rushing games, including a 301-yard effort against Washington. Then came the anonymous tip that changed everything.

Foster was found to have been driving an SUV owned by actor-director Eric Laneuville, a violation of the NCAA’s extra-benefits rule. The organization suspended Foster for the rest of the season. The Bruins dropped two of their last three games, their star running back never suiting up again.

“Any time you have a guy who’s like a first-round talent, monster running back who can get 100, 150, sometimes 200 yards a game and will dominate the red zone, that’s a huge loss,” said David Ball, the former UCLA All-America defensive end who was a sophomore that season. “So it was hard. That was part of it. Another part of it was, man, O-line problems, lack of depth there, so it wasn’t all him, but it was hard.”

Coach Bob Toledo, who declined to comment for this story, once said the incident changed not only the trajectory of the season but also maybe his career. He was fired a year later amid more losses and a long history of off-the-field issues involving players that also included a misdemeanor marijuana charge against Foster before his junior season.

Earlier this month, after settling into a plush seat in the same auditorium where he was introduced to his team, Foster was asked about his reaction to the suspension leading to the premature end of his college career.

“I mean, would that be a violation now?” Foster said, alluding to freewheeling player compensation during the name, image and likeness era. “That’s my reaction.”

So he didn’t think it was worthy of punishment at the time even though it violated existing rules?

“I wasn’t speeding in the car, I didn’t hit anybody in the car, I wasn’t drinking and driving, I wasn’t doing anything,” he said. “But it is what it is, you know? It got me to Carolina, I got to play in the Super Bowl. I mean, I just try to look at it as that — it would have been different if I was doing like crazy stuff and then it caught up to me, but I was just driving a car.”

Character questions related to Foster’s suspension followed him into the NFL draft, where he widely had been expected to go in the first round before the brouhaha.

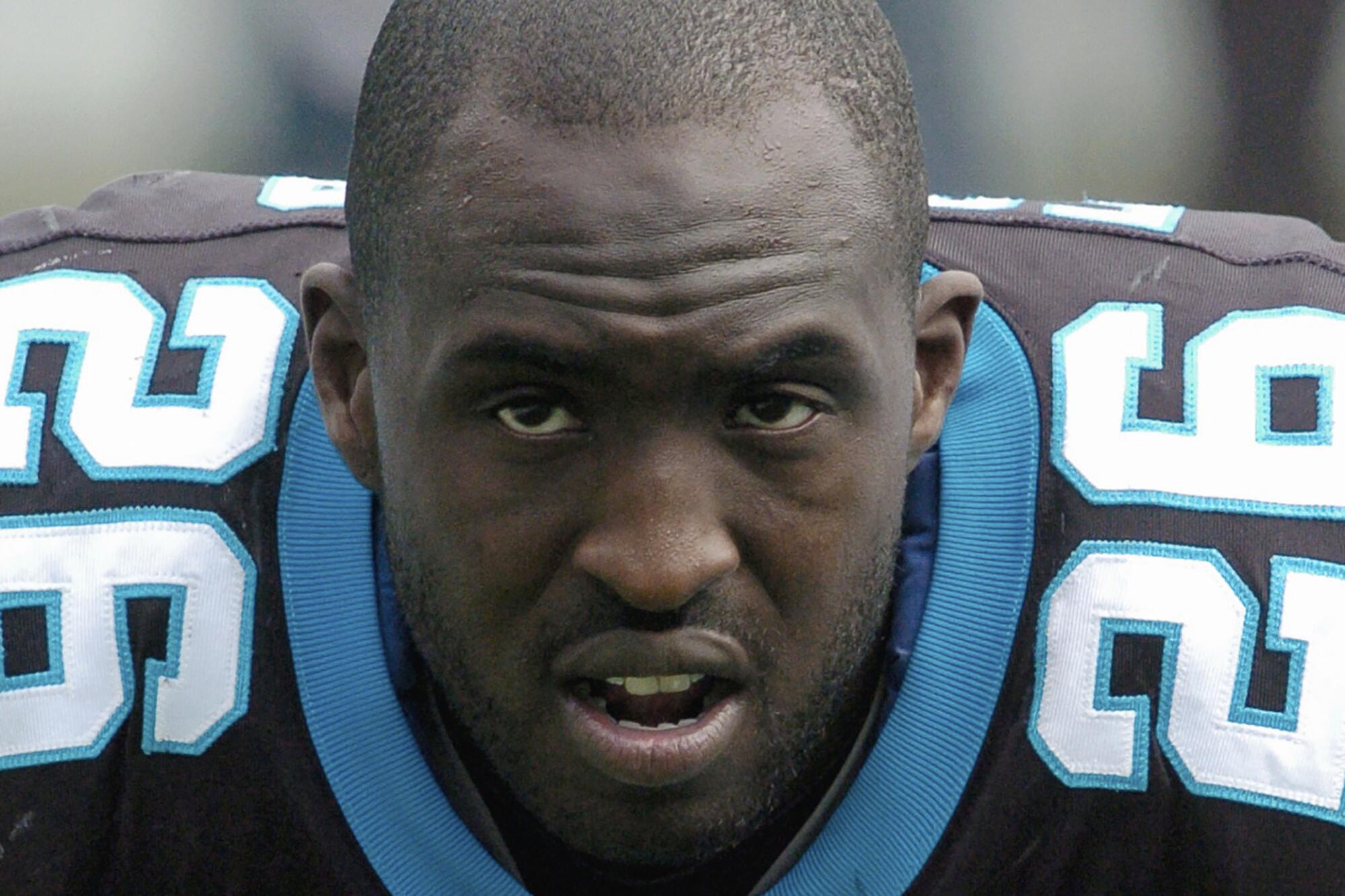

Thankfully, he had valuable allies in Carolina general manager Marty Hurney, a longtime fan of Foster, and Skipper, whose father, Jim, was running backs coach for the Panthers and a confidant of owner Jerry Richardson.

“The off-the-field thing comes up,” Jim Skipper said, “and so the owner, Mr. Richardson, pings me and he said, ‘Listen, we’re banking a lot on your son’s recommendation,’ and I said, ‘Well, if my son said he’s a good guy, I’m going with him.’”

Carolina selected Foster with the second pick of the second round, ensuring a homecoming. Foster was born in Charlotte and still had lots of family in town even after moving to Southern California as a 1-year-old when his father was transferred to the Marine Corps Air Station Tustin.

The running back rewarded his new team with a 61-yard touchdown run on his first exhibition carry. But a week later, Foster sustained a microfracture in his left knee, threatening more than the season he eventually sat out.

“He played his whole career on one leg, really,” Jim Skipper said, “and he had a fantastic career.”

Foster went on to be remembered for two touchdowns during his six-year career, including a short run against Philadelphia in the 2003 NFC Championship that required a second, third and fourth effort as the running back continually shed defenders.

“That’s the damndest one-yard run you’ll ever see,” Jim Skipper said. “I mean, here’s a guy, he broke two tackles in the backfield, he broke two at the line of scrimmage and he broke at least one or two at the pylon when he dove into the end zone, so man, I mean, that right there, there’s no doubt about it that we’re going to the Super Bowl, OK?”

Protecting UCLA quarterback Ethan Garbers is a key to success for the Bruins this season. It is one of five takeaways from the Bruins’ training camp.

Foster’s other timeless touchdown, a 33-yarder two weeks later during the Panthers’ loss to the New England Patriots in Super Bowl XXXVIII, lives on in the photo of the running back diving into the end zone that adorns one wall inside Jim Skipper’s suburban Phoenix home.

Pondering the possibilities had he not suffered the knee injury and a broken ankle that further curtailed his career, Foster surmises he might be somewhere besides doing an interview on the brink of his coaching debut against Hawaii on Saturday in Honolulu.

“Somewhere, feet kicked up maybe, I don’t know?” said Foster, who will turn 45 in January, adding that maybe he would have gone to the Pro Football Hall of Fame induction ceremony this month for himself instead of former Panthers teammate Julius Peppers.

“I’m just kidding,” he said, chuckling, “but you never know.”

Nearly everyone has given him the same advice: Just be DeShaun Foster.

In some ways, that name makes him distinctly qualified to lead the Bruins. He knows the university culture and the challenges facing his players, from the academic workload to the distractions of living in Westwood to the endless cycle of football meetings and practices.

UCLA has gone this route before with former players turned coaches, Terry Donahue leading his alma mater on a glory road while Karl Dorrell and Rick Neuheisel hit dead ends. The hiring of Foster has rekindled visions of another native son restoring the school’s football brand.

“Having someone who loves it and wants to be there and has those relationships and understands how it works behind the scenes a little bit is going to help them,” Ball said, “and I honestly think you’re already seeing how that’s been able to help them with the stuff he’s been able to get off the ground so quickly.”

The rookie coach surrounded himself with a veteran staff featuring a combined 47 years of NFL experience, including Eric Bieniemy, a two-time Super Bowl champion as offensive coordinator with the Kansas Chiefs. An expanded recruiting staff swiftly snagged commitments from four four-star high school prospects. A spring showcase that was part carnival, part football practice brought scores of former players back to campus.

By almost any measure, Foster won the offseason. The coach even poked fun at himself on the first day of training camp by wearing a T-shirt with the slogan “We’re in L.A.” But how will he fare against a killer schedule that includes Louisiana State, Oregon, Penn State and USC? Expectations are low outside the team’s practice facility. Most media polls predict a bottom-five finish for the Bruins in the Big Ten.

Fortunately, being DeShaun Foster means not caring what anyone else says about his team — or about him not saying much at Big Ten media day.

“We’ve got to play ball,” Foster said. “That’s why talking isn’t really my forte because you can talk all you want and you get out here and lay an egg and now what? Or you can not be a good talker and get out here and get these boys to play some ball, and that’s what it’s about.”

If all goes well, Foster will have the last word without saying a thing.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.