Column: Jim Murray: Wonderful Willie

- Share via

The following Jim Murray column was first published by the Los Angeles Times on May 23, 1962. Read our full coverage of Willie Mays, including our obituary, as well as how Mays was instrumental in California’s fight against housing discrimination.

The first thing to establish about Willie Mays is that there really is one.

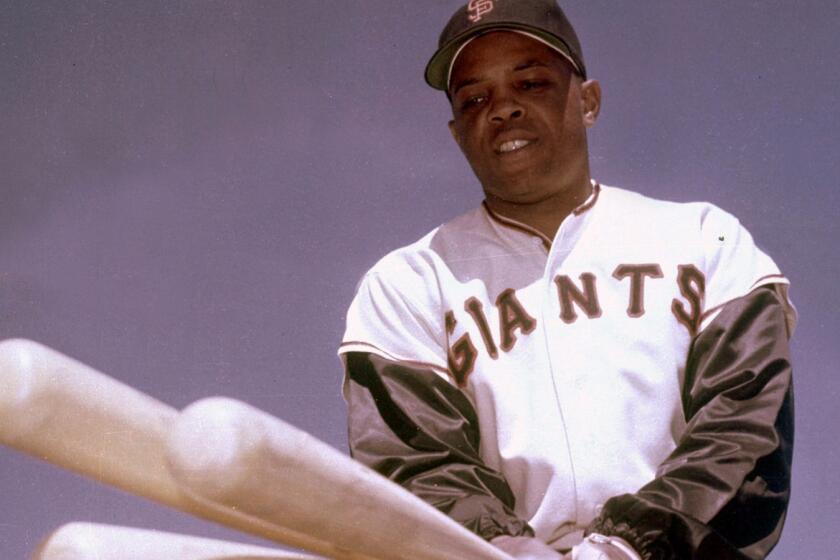

He’s 5 feet 10, weighs 183, has five fingers on each hand, five toes on each foot, two eyes, all his teeth and a nice smile. He’s quite mortal. He makes $90,000 a year but gets to keep only enough to pay off the alimony and the rent on time and is made up like the rest of us of about 87 cents’ worth of iron, calcium, antimony and whatever baser metal a human being is composed of. Only in his case, it’s put together a little better than in the rest of us.

All this is important to know in talking to baseball people because when you mention Willie Mays, several things happen: A film comes over their eyes, their cheeks flush and flecks of foam appear at the corners of their mouths. Listening to them, you half expect to see the Angel Gabriel running around with No. 24 on his back. At the very least, you think they are describing one of their own hallucinations — a combination of Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb and Elmer the Great, a comic strip character 28 feet tall pasted together out of old clippings of The Sporting News or conjured out of a pot of reheated Welsh rarebit.

Willie Mays is so good the other players don’t even resent him. They have his name in standing type in Cooperstown’s Hall of Fame ever since he was a rookie. Leo Durocher started to drool the first time he saw Willie Mays, and he hasn’t stopped since. “If he could cook, I’d marry him,” Leo once announced.

The only thing he can’t do on a baseball field is fix the plumbing. As a batter, Bill Rigney once said, his only weakness was a wild pitch. But he hit one of those in spring practice for a clean single from a semi-prone position. As long as gravity is working they boo him in San Francisco. This makes strong men cover their ears because around the rest of the league they figure anyone who would boo Willie Mays would kick in a stained-glass window.

Part of the trouble is when the Giants transferred to San Francisco, the press there and in New York gave the impression that Willie Mays and the Seven Dwarfs were coming to the Coast with Horace Stoneham and two lame-armed pitchers. They didn’t expect Willie Mays to land there; they expected the waters of the Golden Gate to part and let him walk ashore. Or, if he flew, they didn’t think he would need an airplane. The first time he struck out, there was a gasp as if someone had just let the air out of the town.

Willie Mays, widely regarded as the finest player in Major League Baseball history, died Tuesday afternoon, the San Francisco Giants announced.

It was said his life used to be 95% baseball and 5% cowboy movies. Then he got married, and the ratio went down. His life became only 93% baseball.

He can do one more thing than any other great slugger in the history of the game — steal bases. He is the only man in history to hit more than 30 home runs and steal more than 30 bases a season — and he does it habitually.

He has been shy most of his life. He needs constant reassurance. The product of a broken home in Alabama, raised by an aunt, he never takes anything for granted. He doesn’t drink or smoke and scandal has never touched his life.

Off field, he is a pleasant, rather lonely young man. He had his 31st birthday dinner alone in a St. Louis hotel room with a newspaperman, Harry Jupiter of the San Francisco Examiner. In spring training, he was a frequent dinner guest of a busboy. So far as is known he has never done an unkind thing in his career — except hit four home runs in one day off Milwaukee pitchers. That’s as many as anyone ever hit in one nine-inning stretch.

A 2016 video shows legendary Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully calling Giants great Willie Mays his favorite player, ‘even though you wore the wrong uniform.’

He is modest. When he was with Minneapolis in 1951 and a Giants official got on the phone to send for him after the Giants had just lost 11 games in a row, Willie demurred. “I’m not ready yet. I’m not coming,” he protested. There was a thud on the other end of the line as the man fainted.

The Giants won the pennant that year, but Willie went hitless his first 22 times at bat. Manager Leo Durocher came upon him in the clubhouse. Tears were streaming down Willie’s cheeks. “I can’t help it. I can’t hit them cats, Mistah Leo,” he sobbed. Leo put his arm around him. “I brought you up here to play center field. You are the greatest center fielder I have ever seen, probably that the game has ever seen. Get out there and play it!”

Willie Mays did. The first pitch the next day — off Warren Spahn — he put over the roof. He’s been doing it ever since. “I think I’ll steal less from now on,” he told me Tuesday night, “because I hope I can play for 10 years more.” I got news for him: Baseball hopes so, too.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.