- Share via

Well, I suppose there was never any stopping him. His promoters tried to talk some sense into him, but the pug insisted on blazing this path. He wanted to walk directly through the fire, with his chin held high toward victory. This was what it meant to be a man, right? To be the Mexican warrior he so badly wanted to embody. The paperwork had long been signed and the fight announced. There was no backing out of it, despite how many people thought he was delusional for taking such a risky fight. Didn’t he know? No one had ever survived one of these maulings. Men walked into the ring only to end the night sullen and swollen, broken and confused at how — or when — they nosedived toward the canvas.

It was hard to believe some pretty boy from Victorville had much more of a chance.

But he was assured of his victory. He had no reason to be otherwise. Ryan Garcia, a man-made boxing king of the next generation, wasn’t just going to fight Gervonta “Tank” Davis, the self-proclaimed savage from west Baltimore, in an undefeated vs. undefeated pride fight in the heart of Sin City. He told me, emphatically, that he was “gonna shock the world.” He saw the scrap as his sole moment, the only thing he could currently conquer to prove he belonged with the big boys of boxing.

The fight wasn’t about money. It was about acceptance. He fell in love with what he said he had to do. An excruciating body transformation that got Garcia addicted to sacrifice. Dread. Chopping wood and carrying water. The training he needed, it seemed, he hadn’t experienced before. It was a requirement that eluded a boxer made famous in corners of American culture more apt to celebrate influencers than pugilists.

He knew the mountain he was about to climb was nothing short of immense. To kill off any distractions, months before the fight he moved his camp from Miami closer to family in California. He watched tapes of Muhammad Ali’s upset of Sonny Liston, as a point of comparison for his fight with Davis.

“They thought Muhammad Ali was gonna die,” Garcia said. “There’s no way, he was a loud-mouth, pretty boy from Louisville. It was very similar. They thought he wasn’t ready. They thought he bit off more than he could chew. And they all swore he wasn’t gonna win. And, that was his moment. He shook up the world.”

“That’s why I love this fight so much,” Garcia went on to say, casting a quixotic stare. “So many people have me as the underdog and this is my opportunity to inspire people. And you can’t do that if everyone thinks you can do it. We’re really at a crossroads.

“Either I’m ready now,” Garcia sighed.

“Or,” he deadpanned. “I-I’ve still got some more searching to do.”

He bent his thumbs over each other, one after another. He thought long about what he just said. About what it would feel like to lose to Davis. He stopped, and shook his head, left to right, like a metronome. He couldn’t think too hard about it, or he’d go blank, and stare off until the day ended. He’s always endlessly searching, yearning for hard lessons through a painstaking, trial-by-fire attitude Garcia’s clung to since he was 7 years old. It led him from baseball to boxing, from 215 wins and 15 national titles in the amateurs to a 23-0 record in the pros.

If Garcia needed an answer, he figured fightin’ would provide it. It always did. Because he always won. There wasn’t a world where his sharp left hook couldn’t solve most of his problems. If he truly believed he was on a walk toward a path he couldn’t see yet, the only thing he could do was get in the ring.

“Boxing is the most truthful sport in the world,” he said. “No matter if you’re the good guy or the bad guy, the truth is gonna win. It doesn’t have any bias. ... That’s why I love it: you can lie that you’ve been training hard, you can lie that you’re a better fighter. But, when you get in there: you find out the truth. It squeezes the truth out of you, no matter if you’re tired, there’s really nothing you can do to hide that fact. I mean, you can try, but the truth comes out.

“The sport only rewards honesty.”

At the crown of a gaggle of winding hills spiraling up Valley Vista Boulevard in Sherman Oaks, the prospect made his den. The camp house was Garcia’s home during the peak of his Davis fight camp. A near $30,000-a-month reprieve from his multi-million dollar hillside compound, but close enough to Ten Goose Boxing in Van Nuys, where the hall of fame cornerman, Joe Goossen, would brace Garcia for the fight of his life.

Garcia wanted something different. Even if his first idea was to rent an influencer house. His first thoughts are often wrong, anyway. So the plan was scrapped. He needed to be more focused. Elusive. Private. As few distractions as possible to become war-ready.

So, Garcia tricked out his garage in Porter Ranch to be his personal playpen — each inch packed with punching bags galore. Goossen’s gym still worked at night, when folks stopped trying to steal a glance at the contender in labor, and the glass could be blacked out so he could sink into solitude. That was the least Garcia could do, he didn’t want ol’ Joe to have to keep chasing folks away who were pressin’ against the rickety glass to get a peek at boy wonder.

The camp house was where he could relax, even if it looked like it once moonlighted as a content house. There was a cerulean basketball court, bathed in sunlight most days, where Garcia and his boys unwinded and launched jumpers after tough mornings in the gym. Inside were gray brick walls surrounded by a fireplace, where a smattering of windows showed a distant Los Angeles and featured contemporary portraits of Ali with “Life is Gucci” splayed across his body. Tables carried vintage Polaroid cameras, art of classic rock, the historian Will Durant’s “Study of Philosophy,” life application study bibles, ‘70s novels from Erica Jong about feminism and finding yourself and, of course, as any young man’s pad is sure to need, Dan Brown’s “The Da Vinci Code.”

Eight days before he’d meet Davis in Las Vegas, he was here, running out of the shower to meet his esteemed guests on his fluffy couches. A half hour before he arrived from a strength and conditioning session, a troupe of stylists, belonging to Mike Amiri, gasped as Garcia came into view.

Briefcases opened and black ensembles and silhouettes tightly fitting to his body were wrapped around his shoulders and waist. He looked miscast for “Creed,” but still fit the aesthetic of an underdog.

“When the lights hit this thing, it’s gonna be wild,” Amiri said to Garcia, as the impulsive 24-year old ran his hands along the shimmering, onyx fabric. “You built up this moment,” Amiri said, pointing to Garcia. “It should feel really iconic and stamp it in time.” Garcia could only gush. “I wish you could see how happy my heart is,” he said. “I’m ready to do this s—. I’m not gonna let any of the blood touch it.”

Garcia bent his knees, and locked into an orthodox stance in front of the stylists. He started moving around a dining room table, crisply tapping the tips of his toes across the floor and powering into a statement left hook. He noticed how good the tassels would look on pay-per-view, under the glow of the arena.

“Boxing is the most truthful sport in the world. No matter if you’re the good guy or the bad guy, the truth is gonna win. It doesn’t have any bias. ... That’s why I love it: you can lie that you’ve been training hard, you can lie that you’re a better fighter. But, when you get in there: you find out the truth.”

— Boxer Ryan Garcia

For a few moments, Garcia lost himself in a mirror, delicately examining each square of his midsection, licking his lips every few seconds, rubbing the corners of his head to frame himself into a golden boy pose. After everything was deemed perfect, the tracksuits and ring gear were sealed away. The house emptied and Garcia floated to the kitchen, picking at a plate of chicken and rice his personal chef made him while he was away carving the rest of the weight off his body.

“Yeahhhhhhhh,” he sang, to no one in particular, just the ghosts replaying in his mind in the solitude of the kitchen. He stared into his plate. “I’m him!”

He was a long way from the beginning, when he and his father, Henry, were scraping for everything, sleeping in a van outside of local Walmarts as his father drove Garcia to amateur tournaments, praying the leather he flashed could change their lives forever. There were the nights he had to sleep in the back of those cars, fighting for his dream to come true in the amateurs, and dark moments of a depression so deep as a pro, he considered taking his own life.

Now, designers from Dior to Amiri were begging to be the names on the back of his shorts. Now, so many people were willing to go out on a limb, to believe in a boy who just recently started believing in himself again. Ryan Garcia, boxer or not, was far from where he began.

“Yeahhhhh!!!,” he got louder, feelin’ himself a bit more. “I’mmmmm him!!!”

Garcia’s beef with Davis, he said, didn’t start at a round table with Mike Tyson years ago, when Garcia, barely a credible win behind his pro name, called Davis out over the phone. It goes even further back than their confrontational affray at Bootsy Bellows nightclub on Sunset Boulevard, where Garcia got in Davis’ face and Davis grabbed Garcia and momentarily stole his chain.

Garcia said it began when they were teenagers.

“That was when I was 17, he started talking about my parents and said they ... looked like cousins,” Garcia said. “That started my feeling of needing to put him in his place. He needed to be disciplined.

“From there, I knew: I wanted to hunt him down, ’til I found him and made him take back those words.”

After Garcia beat former champ Javier Fortuna, he and Davis came to the table to begin negotiations in earnest. It took six or seven months, “that’s where every obstacle came my way,” Garcia said. “One by one, I knocked them down. I didn’t give them a reason to say ‘no.’” There were caveats that many seasoned fighters would’ve turned down: a catchweight at 136 pounds, a rehydration clause sure to sap Garcia’s power against a brutalist like Davis and additional weigh-ins to ensure no one stepped into the ring above 146 pounds the next day. “I really sacrificed a big part of my ego and my pride,” Garcia said. “Everything that could stop [the fight], I noticed it and didn’t let it happen.”

What developed was a rift in the normalcy of boxing’s old rules. Say what you will about the nature of a dying game, but at least the youngins were willing to get in the ring. To sign the dotted line in an era of stagnation for the sport’s top fighters. Here were two fighters, perhaps in their prime and with plenty of cultural cachet, brawling for something more righteous than poorly plated gold. In the center of that ring, each was willing to take the necessary risks to prove that they could be the future of our nation’s favorite, withering sport.

Underneath any quest for revenge or fortitude for Garcia, he had a genuine chance to evince belief in any ability we never knew he had. It wasn’t enough that Davis told the public he respected Garcia, or how he thought he may be the best puncher he’d face at that point in his career. So many of boxing’s best and brightest just didn’t believe he had the mettle to mess with someone such as Davis.

We had seen Garcia win, knock out champions, even rise from the canvas and kill off gold medal slugger Luke Campbell and send him into early retirement.

Ryan Garcia ‘couldn’t concentrate on anything’ and explained why he had to stop boxing. His next challenge is proving he can fight again.

There was proof in his power, but also an absence of evidence that it was real enough to beat a true threat. Davis knocked out 93% of his opponents going into their brawl. The power in his hands was catalyst enough to turn men into memes. During his last fight, Davis hit Hector Luis Garcia so hard, he went blind in one eye.

There was ample reason to believe Ryan Garcia was afraid to make that lonely walk to the ring, where no one could save him from the savage of the lightweight division. But, after endless self-reflection and understanding, he knew some things he couldn’t control. He needed to embrace it.

“There’s been times I’ve been scared, and I’ve been nervous, but that’s not gonna determine my action, or my bravery,” he told me. As a kid, he kept questioning how he would react when the angst bubbled in his stomach. “These moments bring that out of you. You’re gonna be nervous and feel the pressure, but these are the moments that are gonna define you,” he said. “So you either take charge of it, or you understand that: maybe this ain’t for me.”

“You gotta be cautious when people are fighting out of fear,” Davis told me a few months before the fight. But he wanted Garcia’s trepidation to take center stage. He wanted to feast on it, to expose Garcia as a pretender.

“You put a C-class fighter in front of me, he won’t do good,” he said, plainly. Davis didn’t believe Garcia was on his level. If he weren’t ready when the bell rang, “it’ll definitely show,” he said. “I’m not comin’ to play wit him.”

During Garcia’s fight camp, there was a common theme whenever I spoke to him over the months of preparation for Davis: He knew he was being counted out. It wasn’t something he conjured by himself, it was the stone-cold truth. Garcia needed the perfect fight to even have a chance at giving Davis a tough night.

The rhetoric of Garcia being in over his head began at the news conferences, one in New York, another in L.A. Mind games were the featured product. In Manhattan, at Madison Square Garden, Davis showed up hours late to the event being streamed on Showtime, leaving Garcia waffling on air complaining about the professionalism of the champion until he was about to leave all together. Handlers urged him to understand that walking away would play into Davis’ hand. If Garcia didn’t want to come off like a punk, he had to sit and stew.

It was the official sound of the gun, the start of the race of mudslinging and mind games. Davis was a polished fighter in the politics of East Coast pugilism, trained by Calvin Ford — a man who was the inspiration for bruisers in “The Wire” — after being bred by Floyd Mayweather Jr. Davis knew how to take a man out of the ring before he even threw the first punch.

When Davis did arrive, he kept it short and sweet. He mocked Garcia for showing up to work on time, and promised to give the fans exactly what they wanted to see.

The two left their seats a few minutes later, to get face to face for the cameras. Instantly, it got heated. Davis, who was mostly demure during the news conference, sprang alive to inform Garcia that he “wasn’t built like that” and that he would “knock you the f— out.”

The next day at the Beverly Hilton’s Wilshire Garden, on the same terrace where Canelo Álvarez and Caleb Plant got into a brawl two years earlier, media pooled onto the grass to await the combatants. Forty-five days until the fight, though, no one was around. Garcia was holed up across the garden at the Waldorf, standing on the balcony overlooking the scene with the rapper YG next to him. He wouldn’t be embarrassed on his home turf after what Davis pulled in New York. So hours later, there was the stage and neither boxer was on it.

Though these were merely stunts of inflated machismo, but you have to admit: Bad blood was good for boxing.

Eventually, Garcia, decked in all white, was anchored by mariachis as he swung onto stage. He was all scowls and hardened cheekbones. Tyson used to say that “you never lose until you give up,” and at that lectern, Garcia was nothing if not determined. Fiery and focused. Angry, at a minimum.

Davis came out in all black, blasting Lil Uzi Vert’s latest showstopper and got right in Garcia’s face, shoving and pushing him, putting his fist on Garcia’s chin, only for the 5-foot-10 Californian to wiggle away.

This time, Garcia to the cheers of his local fans, told everyone he’d send Davis to the hospital. Only, Davis wasn’t buying it. “He’s putting on a front for the people,” Davis said. “I see a guy who’s an act. That’s who he is. That’s what it is.”

Garcia tried not to say anything, contorting his face into an unpracticed grimace, while Davis kept swinging for his pride.

“When you saw me in the club, what did you ask me?” Davis said to Garcia.

“I said, ‘Are we gonna fight?’” Garcia answered.

“You said, ‘Are we gonna be friends after the fight?’” Davis said.

“I said ‘We could be friends!’” Garcia countered.

Davis smiled and looked at the crowd, as if we should understand the display he was trying to make of Garcia. Davis showed up, ready to fight. Garcia showed up, ready to be homies. It was savvy by Davis , reminiscent of how his mentor, Mayweather, needled Garcia’s boss, Oscar De La Hoya, during their historic fight in the aughts — going as far as to steal De La Hoya’s food from his plate during a promotional stop. If there were any nerves around, the consensus was that it wasn’t from the blue corner.

Garcia even had the opportunity to play the moralist. Davis has been arrested four times since 2017. The first two involved fights outside of the ring. In 2020, he was accused of leaving the scene of a hit-and-run that injured a pregnant woman and three others in Baltimore. After a judge rejected his plea deal, he is scheduled to be sentenced on May 5. Also in 2020, he was charged with battery in Miami-Dade County for grabbing the mother of his child at a charity basketball game. The prosecution later dropped the charges. And in December 2022, he was booked in Broward County and charged with battery after striking a woman. The woman later recanted her testimony and urged prosecutors to drop the case.

Garcia merely thought Davis didn’t have a solid moral compass.

“It’s quite obvious, I think.” He chuckled softly to himself. “Some people, it takes time for them to learn. It’s a gift to me to know what’s right or wrong in life, even in little instances. That’s not something you teach that much, and I don’t think he has it.”

Coming out of the two news conferences, folks around the sport still weren’t sold on Garcia as the hero of the brawl. “He’s a marketable kid,” Raul Marquez, the former IBF junior middleweight champ with over 40 pro wins, told me. He saw Garcia’s talents. Everyone did. But the man who was De La Hoya’s roommate at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics also saw a potential punching bag. “Look at the guys Tank has fought and the guys Ryan has fought,” Marquez said. “They don’t even compare.”

“He’s good looking, speaks well and carries himself well. And social media is big right now, he’s got a lot of followers, but that’s what makes him. He talks a good game, but he’s still learning. I’m not sure if this fight could be too soon for him.”

Some deals in boxing are high risk, low reward. Garcia likely earned respect by signing the paperwork and talking the talk at the pressers, but actually going through with the challenge, especially with all the stipulations involved, wasn’t the most advisable decision.

“I know how fickle this thing is,” Andre Ward, America’s last Olympic gold medalist in boxing, told me. “If that [rehydration] clause is the difference between him taking a good shot and getting up or taking a good shot, not recovering and staying down because those last few pounds got him? Who’s gonna be there to say anything positive about him?

“He’s not gonna get rewarded for that. He will before the fight, but if that happens to be the case, he’s not gonna get rewarded for it. You gotta respect [Garcia],” Ward gritted his teeth. “But, I don’t think that was a good business decision.”

In boxing, sometimes, you don’t get what’s fair. You get what’s negotiated. And no matter how much anyone makes: Ignorance remains prizefighting‘s most heralded currency.

“I don’t mean this disrespectfully,” Ward said. “But if Ryan Garcia clips Gervonta, or hurts him, or stops him, it’s gonna be by accident. He’s got a lot of ability, but it’s not harnessed. It’s not controlled.

“Ryan makes some cardinal mistakes, and when I watch him train for this fight, I don’t see him making adjustments. I see him hitting the mitts, and his chin is not only up in the air, but there’s no defensive move after he punches.”

It was almost like Ward was pleading for Garcia to get some protection.

“Ryan,” he’d go on to say, almost ashamed. “It’s his looks. I became aware of Ryan through social media before boxing. His skill set didn’t attract me. When you come in the door like that? You gonna get handled like that until he proves otherwise … he doesn’t look like he’s tough. He doesn’t look like he can handle the moment. That’s what’s hovering around [Garcia].

“He’s gotta prove that he can.”

On the last Friday in March, 22 days until fight night, Garcia walked into Ten Goose Gym. He was armed only with his father, who also acts as an assistant trainer; his brother, Sean, who’s also a pro; and a few friends. Goossen had been there for an hour already, readying the gym for his prized pupil and warming up Danny Paro, Garcia’s stout sparring partner that evening.

Garcia sat on a stool with Samir Dos Anjo, his trusted mitt man, and got his hands taped. Behind him played a virtual testimony about Christianity. A woman preaching said that “I can’t do anything without you, God.” Hymns from the Hillsong Church soothed the gym for Garcia’s warm-ups. He strapped on blue headgear and gold Nike boots and closed his eyes.

Goossen sat on the edge of the ring, dressed in denim head to toe, hair slicked back like Elvis, if the King’s hair was dyed dirty blond. He’d mentored so many cats from the corner — Shane Mosley, Riddick Bowe, Rafael and Gabe Ruelas — that he was starting to forget their names. Bear with the man, he’s 70. But Garcia was the fighter who, apparently, most made his eye gleam. “This man brings a lot of knowledge and experience I can’t buy,” Garcia said. “He has things that I can’t see because I ain’t been there, yet.”

When the fighter was ready, he turned and lowered his head by the corner, as Goossen whispered instructions in his ear. Henry poured water under his mouthpiece and Garcia’s face went cold.

Henry turned off that new gospel to leave purely the sound of the mitts. Garcia bit down on the mouthpiece, and went to work.

Ryan Garcia, a 22-year-old from Victorville, was knocked down but recovered to beat Luke Campbell. The rising star is not a finished product, though.

The problem was the same, though, even back then: His defense was lazy, too rhythmic in how he set it up, leaving his chin exposed except when in his high guard.

Garcia said of this critique that, “defense is more about awareness and how good you can sense a shot coming. I’ve seen people, they always have their hands up, but they always get hit all the time, too.”

His offense was scattered and rudimentary. He was either overconfident in his talent, or overcommitting to his blows. When the speed of the fight slowed, he grew impatient, trying to snipe left hands and frame his opponent into range rather than moving them there with his feet or combinations. He pawed more with his left hand than he used it, and worked more behind his jab than throwing pot shots all over the ring. It was clear he and Goossen worked on something. Garcia was a natural talent in the ring. But, he was still too upright, still too hesitant to fire those lightning bolt jabs, too unsure of his own might in front of a 4-1 pro even as he pressured him for six rounds.

“Look at your face,” Goossen told him after two rounds. Garcia was already getting puffy and red around the eyes. Going into four, his spit was popping on the tarp from some nice hooks. He put Paro away, of course. Bloodied his nose good, too. But, he seemed tired after six, more willing to get on his bike and move around the ring than engage in the center of it.

After he finished quick work of Paro he went over to the mirror and looked at himself, seeming exhausted. Goossen fed him some water before he shadowboxed.

His folks clapped when he was done for the day, and unwrapped his hands. He and I sat on the edge of the ring, and I thought I owed him the decency to keep it real with him. He kept saying for the duration of camp that the “truth would come out in the ring.” Did that still apply if he got whooped?

“Yes,” Garcia said. “Because somewhere I went wrong. I was off on my calculations and my search. Maybe I overlooked a certain part of his game, or overestimated my abilities because I didn’t think he was that great. There’s some truth in it that I have to find out.” But, even then, he was resilient. “That’s the beauty of boxing. Even if I can’t see it. It’ll be shown in the ring.

“If I can, honestly, step in that ring in harmony and perfect tune and I still lose? Then that man is really great. He really is that guy. I know I’m that guy. I know for a fact. But we’re just gonna have to find out.”

A few nights later, Garcia returned to Ten Goose for another night of sparring, this time accompanied with another pro: Toka “T Nice” Kahn Clary, another lil’man with a 29-3 record, someone as dangerous as Garcia could get two weeks before facing Davis.

Tonight, Garcia’s family were with us inside. His mother, Lisa, came in with Andrea, Garcia’s wife. Their daughter, Bella, bounced around the ring in a pink jacket and Ugg boots while playing games on a cellphone.

A flush of cameras accompanied a stoic Garcia into the gym. His father turned on “I Won’t Move” from Life.Church Worship to get Garcia going. There was silence around us. Just a contender readying himself in the storm of his own desire.

“You ready?” Goossen asked.

Garcia closed his eyes, prayed, and nodded to his coach.

“Next bell!” Goossen yelled.

Ding. Ding. Ding.

Kahn Clary imitated Davis, slow and prodding, methodical and waiting to counter.

Garcia stalked him around the ring. His family held their breath.

Kahn Clary crowded him on the ropes, using feints that fed into hooks, body shot combinations and crosses. Kahn Clary had Garcia running away.

“Don’t’ get frustrated!!” Goossen yelled. “Reset and work!”

The bell rang. Garcia came out of the corner and fired three straight hooks.

“Woaaaah!” Kahn Clary said through his facemask, blinking his eyes quicker. The punches got sharper and stung. “Mhmmm, Mhmm, that’s good!” Kahn Clary said. The force coming off Garcia’s punches shook the south side of the ring.

Goosen nodded, proud. After six rounds, he had Kahn Clary bent over in his corner. They stopped and put Paro back in who got it bad. His head was bouncing off his headgear like a basketball behind Garcia’s jab, a thing of beauty that left Goossen whistling.

“Excellent!” he said.

“S—!” Paro said.

The bell rang, again and the onlookers clapped loud.

Garcia stepped between the ropes to the applause as his father loosened his waist guard and dropped it to the plunk of Goossen’s red, white and blue splotched linoleum. Garcia was gassed, mid weight cut, after 12 rounds of hard sparring in his boots. But, still, he moved people out of the way and stood, alone, in front of one of Henry’s standup reflex bags, the same ones he hit that made him a star on the internet.

“Please don’t break it this time,” Goossen begged. He said, in this camp, a dozen have gone. And in Garcia’s life he’s killed more than 100. The only sounds left for the night were the grunts of work going into the heavy bag.

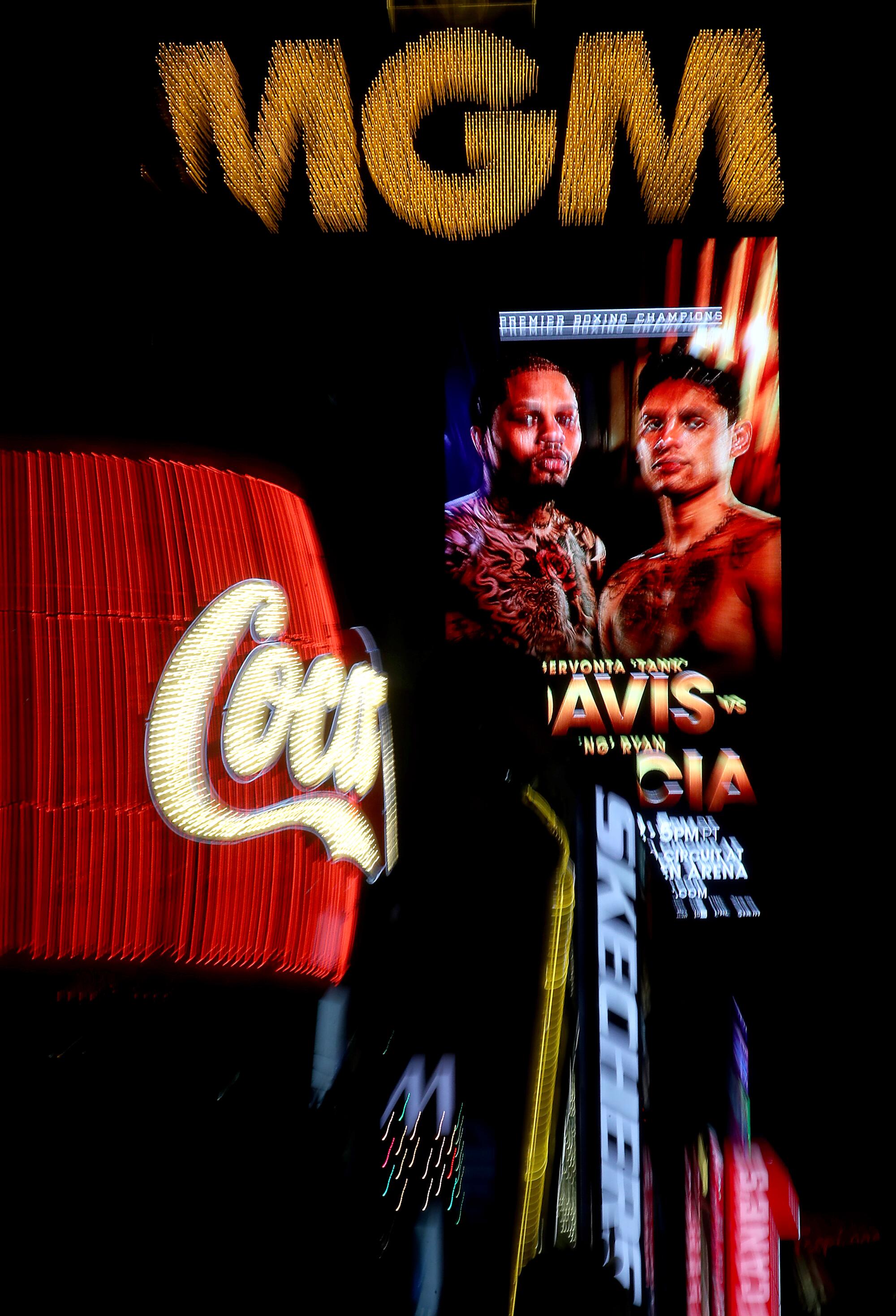

When fight week came, and all the media and the pretenders were pushed into the KA Theater inside the MGM Grand Hotel, Ford, Davis’ trainer, only promised the world one thing.

He looked up from the dais that held him, Davis and Leonard Ellerbe from Mayweather Productions, and stared at Garcia, who was anchored by Goossen, his father, De La Hoya and former champ Bernard Hopkins.

“Be prepared, young man,” Ford said.

He said he didn’t train Davis for a knockout, he trained him to punish Garcia and enlighten the division about exactly who Davis was.

“I want you to feel it,” he said. “I’m sending the message to all of them, through you. We gonna put some knuckles on ya.”

Garcia, pale from the weight cut and groggy as he hovered around 135 pounds, didn’t offer much for a response.

Originally, the two upped the stakes to their megafight. Garcia and Davis appeared on a livestream via Instagram and wagered their entire purses on the fight. Davis said he called Garcia’s advisors to get it in writing, but they wouldn’t let it happen. “He’s scared,” Davis said, before promising to break Garcia’s jaw.

“I’m tellin’ you,” Davis said. “You’re goin’ to sleep … don’t even bring your mother or your daughter [to the fight]!”

Garcia tried to fight back.

“You’re not gonna punish me, no chance,” he said. “You’re out of your mind. You’re talking to the wrong guy. This is where everything catches up to you. … You’re gonna learn the hard way.”

“What hard way do you know?” Davis shot back. “Just make sure you been practicing keeping your hands up.”

Garcia seemed confused. It was almost like Davis had inside information the more he kept talking. Davis revealed what he’d been suggesting through backdoors for weeks before the fight: that he had a mole in Garcia’s camp. There was a thought that it was Erdenebat Tsendbaatar, a Mongolian Olympian and a 5-0 prospect who said he hurt Garcia during sparring sessions. “Ryan went to the hospital and I went home with half my salary,” Tsendbaatar said during a video circulating on the internet. He said he got paid $6,000 a month before getting the ax.

“He doesn’t have the fundamentals at all,” Davis said on stage. “If Joe Goossen was such a great trainer, fix his fundamentals. All he relying on is that weak-ass hook. He got no defense, no footwork, no head movement, no nothing. He don’t have nothing, man. Get him outta here!”

He merely saw Garcia as a stepping stone, a joke, someone unworthy. Garcia resented that, and any notion that he was a faint-hearted fighter.

“He ain’t s— of a fighter!” Garcia said, perking up. “Why do you need all of this for a non-complete fighter?”

Goossen craned his head back and let out a big laugh. “You wanna watch me train tonight? You can! You wanna come and learn something? You can, too! You can pay all the people you want to come and see me.”

As Garcia walked into the arena, his face appeared on the big screens of the stadium to the roars of the crowd. He was in all-black, walking down the dark hallways of T-Mobile Arena. No one could protect him now. He was all alone. Him versus the world. Him versus the crowd. Him versus himself.

When Davis appeared, the boo birds rained from the rafters. He was the WBA lightweight champion, the most dominant small fighter Americans had seen in nearly two generations, but in here? Out West? He was trying to stop a homegrown phenom from his dance with destiny. The wall blocking a West Coast king who made himself a household name everywhere from Oxnard to Santa Monica knocking fools out from every ZIP Code in Cali. Tonight, Davis was only the enemy of the state, on a mission to inflict memorable harm.

Fighters of every generation sat down by the ring: Tyson, Sugar Ray Leonard, Manny Pacquiao, Stephen Fulton, Caleb Plant, Devin Haney, David Benavidez and the Charlo brothers. Rappers and entertainers from Damian Lillard, Future and Post Malone cozied up next to them. There was no space for anyone, no matter how much currency or capital you commanded.

The bowl was filled to its capacity long before the fight began. The mega fight earned $22.8 million, the fifth-highest gate in Nevada boxing history. And more than 1.2 million bought Showtime’s pay-per-view coverage. There would be no hiding.

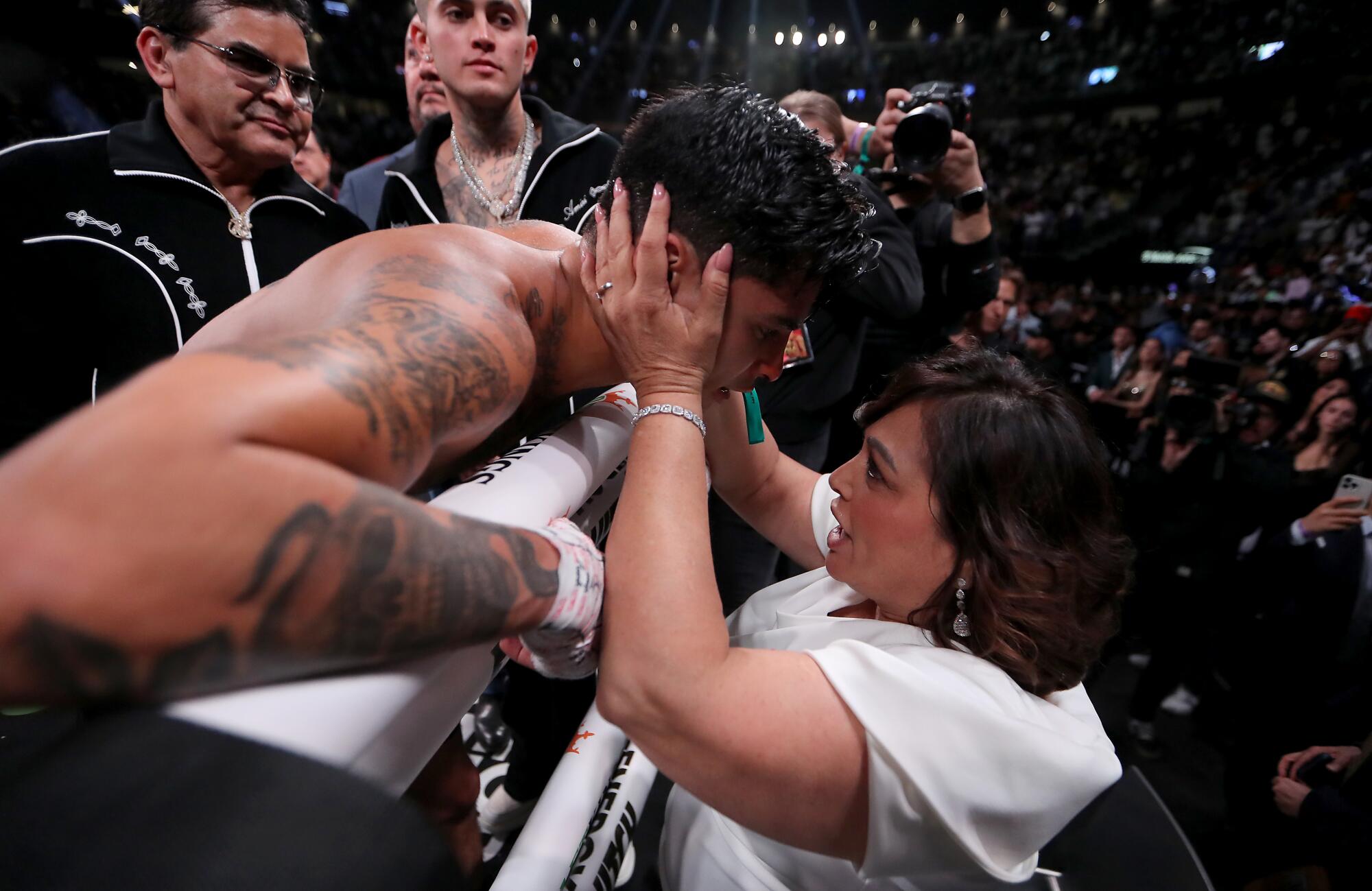

A few minutes before the fighters walked out, Garcia’s wife and mother sat ringside.

Suddenly, the lights in the place went dark. “Oceans” by the Hillsong Church blared from the speakers. A single light beamed toward the entrance from the locker room to show Garcia, hands out, praying as he walked out.

It was a striking scene, Davis in the green and purple of a Monster, Garcia in the shimmering black wonder of a shadowy contender, wearing the same gold boots he wore to practice in Goossen’s gym.

Garcia was no “León de Culiacán,” but the lion roared as loud as he could. He came out showing the jab and lead hook early while Davis circled the ring. Garcia was the aggressor, backing Davis into a corner and pressuring him through the round. Each pop from the high guard was a red flash in the night.

“Tank you suck! Tank you suck!” chants started coming from the crowd. It was almost like we all wanted to believe in the magic Garcia brought to the ring. Garcia was standing in front of the mauler too long, but he won the first round.

It got more physical in the second, and the crowd jumped after Garcia landed a hook that shifted Davis’ braids. The pace was increasing. People stood to their feet, hungry for a knockout, desperate to see if Garcia could actually pull it off.

But, just like that, reality set in.

Davis cracked Garcia with a counter straight and sent him crashing to the mat. Garcia got up quick, but he wiped blood from his nose as the round closed and walked to his corner noticeably disheveled.

Goossen tried to calm him down. So did his father.

It was just a wake-up call. The fight wasn’t over yet if he didn’t want it to be. That was all the red corner could do to motivate their fighter. But the truth was that the dance was done.

Davis rose from his corner smiling as he watched Garcia slow the pace, avoid him and anxiously fire punches with no combinations or destination in sight. Round after round, Garcia was losing the fight. Davis left the corner showing his teeth, talking to referee Thomas Taylor mid-fight. He placed a shot near Garcia’s lung and beamed. “You slow, you slow!” Davis said.

Garcia’s face was getting swollen, puffing with crimson around the bridge of his nose. Garcia went to his corner puzzled, shaking his head. Goossen begged him to slow his breathing, to stay cool under the weight of the moment.

But, by the fifth round, Davis was picking at his food. He’d downloaded everything he needed to know to put Garcia away.

The body shots started increasing, and Garcia began to cower and covered up, like he had enough of the Davis’ power.

The crowd didn’t give up on him, chanting “Ryan, Ryan, Ryan!” into the sixth, but Davis kept slamming him with hooks, changing levels and battering his midsection. Garcia spat out a clump of blood between rounds. He clipped Davis with his signature left hook, but right before Davis lowered himself and placed an armor-ripping shot to Garcia’s liver.

The boy’s face rippled and he began heaving while keeping Davis away from him. But he was overcome with pain and crumpled into the corner, collapsing onto one knee, while bleeding from the nose.

Taylor ran over to him, but it was too late. Garcia looked up, like he was blinded from the lights. He didn’t make a 10-count and Taylor called the fight.

“F—!!” Garcia yelled over the ref’s shoulder.

Ford ran around the ring and dapped his homies in the crowd. “I told you!!” Davis’ trainer yelled to whoever would listen. “And we barely even touched em!”

Henry consoled his boy in the red corner, and so did Sean as they hugged in agony. Opposite of them was Davis, standing at the top of the turnbuckle, ecstatic at the walkoff moonshot he’d predicted for months.

An hour after he prayed for victory in front of 20,000 fans and walked out of the ring in a cloud of defeat, Garcia reappeared in an empty arena. He sat on the stage for his post-fight news conference looking like he’d seen a ghost.

He scrolled endlessly through his phone, his head down not looking at any of us, until his advisors told him it was time to talk. He released a sigh and tried to exude some confidence. The media gathered there all wanted to know the same thing: Why couldn’t he answer the bell? Why didn’t he get up?

“I don’t got no excuses,” he said. “I just couldn’t get up.”

He was impatient in the ring, he said, even to the point of boredom. “Someone a little more disciplined than me,” he admitted, “... would do better” against Davis. “You gotta be careful with Gervonta and play it smart. I didn’t play it smart.” Frankly, he said. “I was being stupid, yo.”

Champions across the hurt business had far harsher criticisms, all layered in an air of genuine disappointment. Mexican heavyweight Andy Ruiz said Garcia “gave up” and “he should have risked his life more.” Former titleholder Sergio Mora was baffled by Garcia’s lack of variety in his offense, saying he “had no game plan.”

Hopkins, a Garcia camp advisor and devastating middleweight champ in his day, said upon hearing Garcia apologize in the locker room after the fight, he told him to focus on fixing his fighting style because he was “not great now.”

Maybe the most brutal was from the legend Julio César Chávez, who swore he’d never watch another Garcia fight again. Perhaps, then, it was no surprise that Garcia swore off the 135-pound ranks for good instead of seeking a rematch, wishing Davis his blessings, before bidding us adieu for the evening.

As Davis climbed the stage to answer some of the same questions, Garcia’s advisors were trying to get him to leave the arena. His night was over, and some of his friends were waiting to party with him and booze away his loss. Garcia, ever the superstar, knew he couldn’t dash from Vegas without the flash of one last light. He didn’t want Davis to think he harbored any hatred for him. Far from that. The fight was over. He thought they should take a selfie and exchange numbers.

“But,” he whined, to one of his advisors as they started to pull away. “I wanna say bye to Tank first!”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.