- Share via

This would be no cakewalk for Trae Young.

Sure, the hundreds in attendance to watch the Atlanta Hawks All-Star guard grace a Drew League game Saturday oohed and aahed after every silky jumper or double-clutch layup. Yet “Ice Trae,” as he’s informally known, didn’t exactly dominate as his Black Pearl Elite team lost 103-100. And the nickname-based barbs boomed across the gym from the microphone of announcer Jorge Preciado.

“I wanna see the igloo, Trae! I feel like it’s the Mojave Desert.”

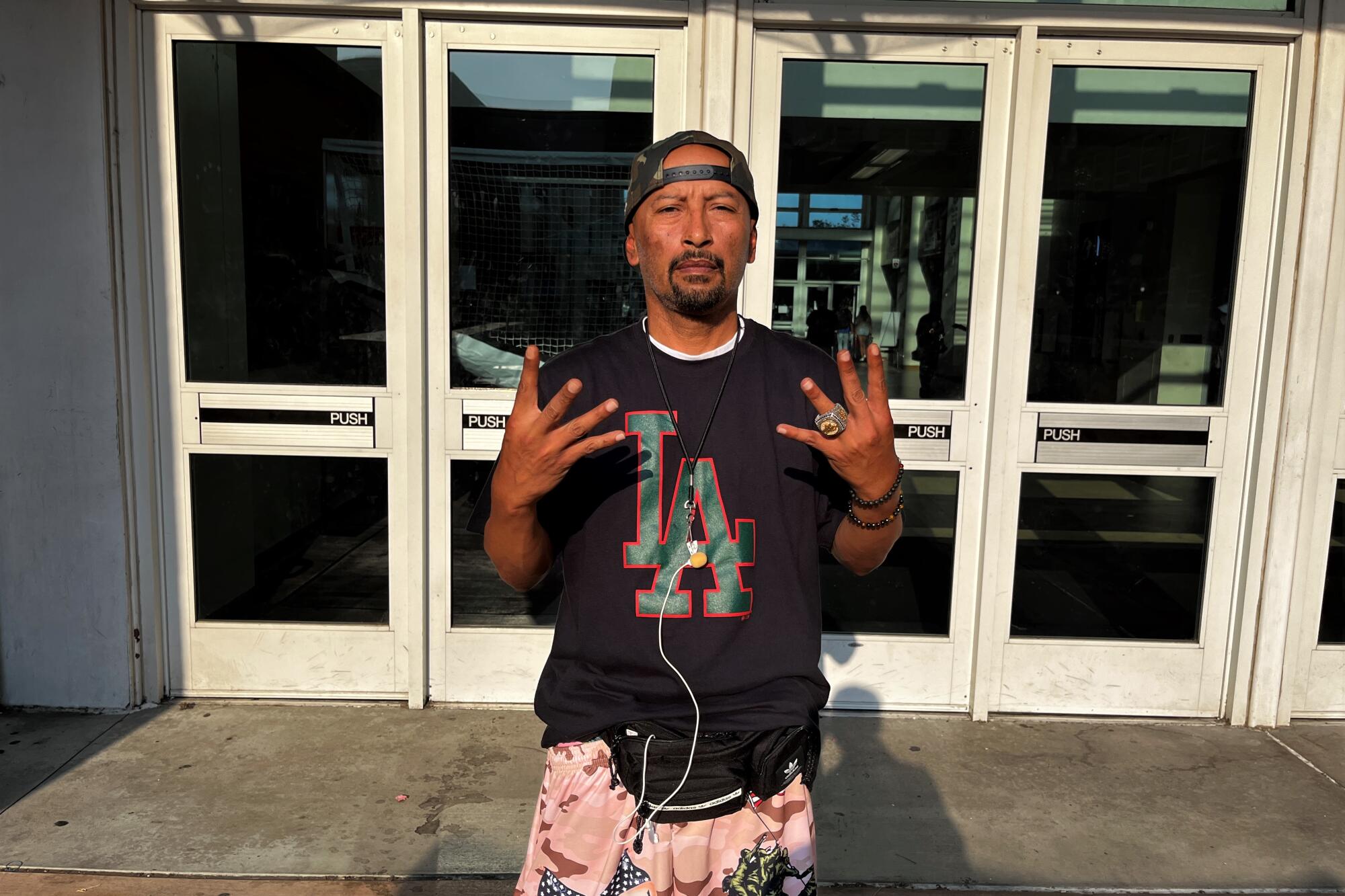

Quickly, it became apparent that Young’s most vocal challenger wasn’t a member of the opposing Citi Team Blazers, but rather the 5-foot-something man, often known as George, with the backward camo cap patrolling the sidelines.

“Young was getting a little bit of the work from Jorge,” said longtime Drew League DJ Jason Beresford.

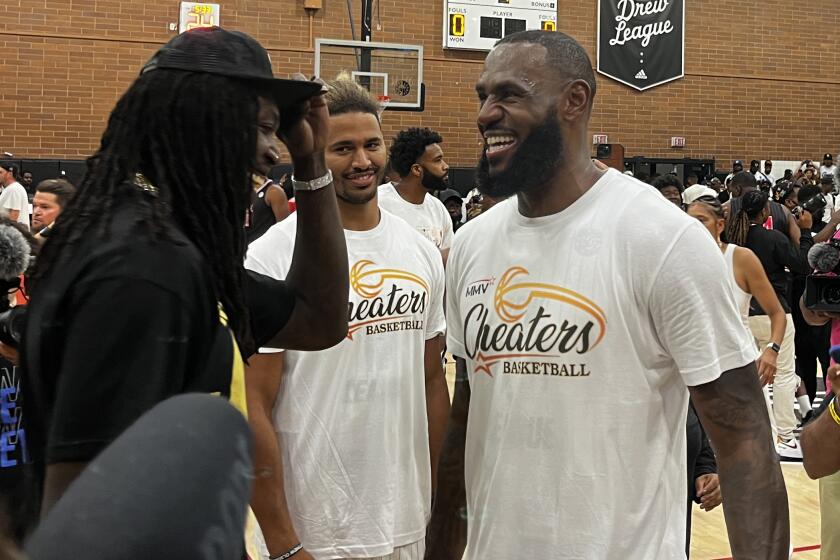

Everyone gets the work. LeBron James even gets the work. When the Lakers mogul pulled up to King/Drew High on July 16, Preciado gave him loud grief for missing a couple of key free throws.

“Smoked it!”

“You can’t just come in here and think you’re a regular player … your pride is on the line,” Beresford said. “And Jorge will let you know about it.”

No excuse — just produce.

Preciado, with his booming “da-da-DA” cadence and unfiltered announcements, embodies the Drew League’s very motto from the tip on summer Saturdays. He’s not just the man who has held the public-address microphone for 25 years.

“He’s the voice,” staffer Timothy Giles said. “He’s the heart of the Drew.”

Before he started camping with his microphone in a rickety black office chair next to the scorer’s table, before he was given the nickname “Chick Hearn-andez” and called himself “the Diplomat,” Preciado was just a dude trying to get a job at a supermarket.

Then, Drew League director Dino Smiley told him he should come announce, even though he hadn’t before.

“I was like, ‘No way, Dino,’ ” Preciado said. “I was so scared to get onto the mic.”

Of course, Smiley had come to know Preciado well. The local kid was a self-described Drew League “fanatic.” At 12, Preciado showed up for the beginnings of the league, when it was held at Drew Middle School.

Referee Christopher “Peaty” Wrenn, a member of the team that won the inaugural Drew League championship in 1973, had to keep urging a young Preciado to get out of the way or players would bulldoze him. It became a running joke between them: “Jorge, get off the court!”

Preciado still hasn’t given way. Even after his first game, when he announced a player, Maurice Spillers, as “Tyrone Spillers.”

“I said it confidently, too,” Preciado said. “Like, ‘Bow’!”

LeBron James played in his first Drew League game in a decade Saturday, scoring 42 points and drawing legions of fans eager to see the Lakers star up close.

Preciado says everything confidently. And without context. One second, he’s loudly drawing the crowd’s attention to NBA forward Darius Bazley’s pink-and-blue sneakers. The next, he’s telling the audience it’s “cuffing season.” The next, he’s belting out lyrics from Tha Dogg Pound’s “New York, New York,” an alley-oop to Beresford to blast the song over the loudspeakers.

It’s auditory chaos. Preciado’s voice fills the gym, and spills out of the double doors into the school’s halls. It adds an unmistakable buzz to games that would otherwise be the sound of claps and the squeaks of sneakers.

“You can tell when Jorge might step away to use the phone or use the restroom when he’s not here,” Beresford said. “You can tell something’s different.”

The Drew League has a culture. It’s grassroots, speaking to South Los Angeles, said Michael McCaa, chief financial officer of the league. It’s “a smattering” of basketball, of viral dunks and flashy crossovers. It’s a sampling of music, of thumping bass and stars like James shimmying along to a bouncing beat. It’s a smattering of style, of celebrities like Lil Wayne and Quavo chilling in courtside seats.

All set to Preciado’s intonation.

“Jorge is the centerpiece of that culture,” McCaa said.

Three months ago, the Drew League staff walked onto the King/Drew High court again. There were no decals on the floor, no Drew League banners on the walls. After COVID-19 brought two summers away from King/Drew, they were happy to simply stand in the empty gym.

“It’s home,” Giles said. “[Like] you on a trip, and you come back, and you get that ‘Aahhhh’ feeling.”

To them, the return to King/Drew feels more natural than playing last year at St. John Bosco High in Bellflower. It has a deeper significance — the league is heavily centered on the community that gave it birth.

“It’s not a lot of stuff going on in our city that’s like the Drew,” Giles said. “The Drew brings out a lot of … superstars, singers, a whole bunch of good energy that inner-city kids wouldn’t be able to see.”

When Giles was a kid at Drew Middle School — and before that, at Russell Elementary School — Preciado served as the school security guard. It’s special, and all “within community,” that the two now work for the Drew League, Giles said.

“If he was to retire right now, it would be hard to find another Jorge,” Giles said. “There’s no one like him. He’s special to the Drew, and he’s special to the community.”

This Saturday, the day of Young’s appearance, Preciado tried to keep himself in check. He was rolling around in that office chair, “acting a fool,” during LeBron’s appearance the previous weekend, Preciado said.

Yet you can’t take the Preciado out of the Drew League, and you can’t take the Drew League out of the Preciado.

“Ice Trae misses two free throws in the clutch,” he yelled as Young stood at the line, an audience member falling over laughing. “Lukewarm!”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.