Malcolm Gladwell podcast examines iconic 1968 Olympic protest and its San Jose roots

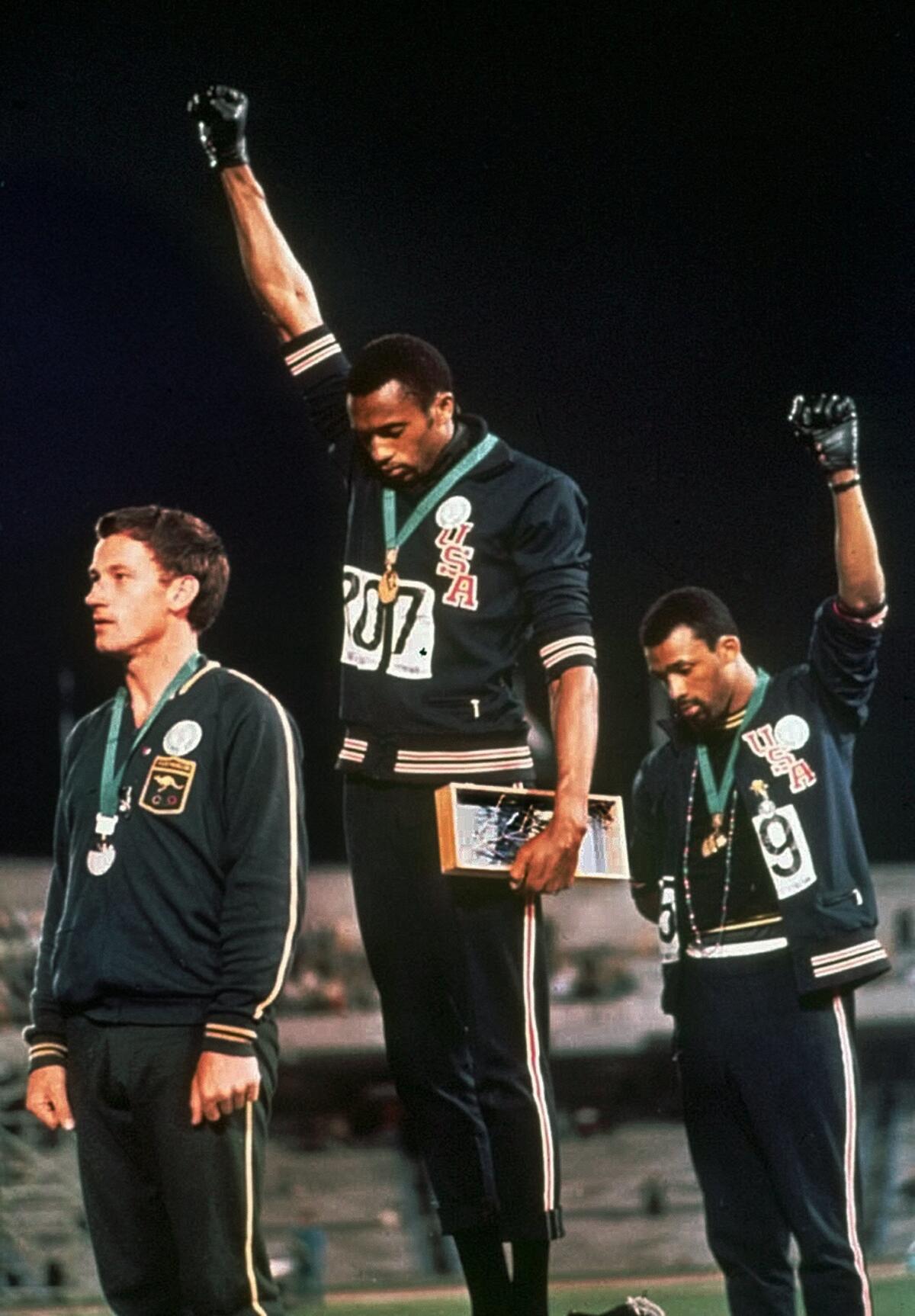

As âThe Star Spangled Bannerâ sounded, tension extended through their arms and into their clinched, black-gloved fists. Tommie Smith and John Carlos wanted the world to know Americaâs great stain.

But it was not rigidness as displayed in the gold and bronze medalistsâ hands that placed the American sprinters onto the podium at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. It was relaxation.

Their coach at San Jose State, Bud Winter, cultivated a new sprinting technique. No more tensed jaws. No more balled fists. Instead, open palms. A smooth gait. A softened face for optimum speed.

The breakdown of Winterâs running revolution kickstarts âLegacy of Speed,â a new podcast from Malcolm Gladwell, a New York Times bestselling author. Inspired by the iconic photo of Smith and Carlos at the 1968 Games, the podcast explores the rise of San Jose as âSpeed Cityâ and the background of the sprintersâ protest after their 200-meter run performance.

âItâs this moment of activism and protest that absolutely stunned the world,â Gladwell said. âAnd we wanted to understand what happened, how did that come to pass ⌠and what were the reverberations of that act?â

Winterâs technique helped the San Jose State sprinters become among the best in the world.

Gladwell was struck by arguably the most famous photo in sports and created the podcast to introduce the story behind it. The intersection of the International Olympic Committeeâs objection to any sort of protest; San Jose emerging as an unlikely breeding ground for sprinters, earning the nickname Speed City; how the San Jose sprinters in the photo decided to protest and inspired others to join them; and the aftermath.

The Times has previously reported IOC president Avery Brundage, who supervised the 1968 Olympics, was widely known as racist and antisemitic. Brundage greenlit the 1936 Olympics to take place in Berlin despite Nazi rule in Germany.

Years later, Brundage and the IOC wanted to invite white supremacist regimes from South Africa and Rhodesia to the Games. They also pushed amateurism, stressing athletes should perform out of pure love for sport and for no financial compensation.

The West Marine U.S. Open Sailing Series is in Long Beach during the weekend, training competitors on the same waters that will host the 2028 Olympics.

The podcast highlights of this put the IOC on a collision course with the sprints being developed in San Jose amid difficult circumstances.

Winter had limited scholarships available, so many of his athletes, largely recruited from inner-city neighborhoods in the Bay Area and Los Angeles, struggled to eat in the city plagued by racism.

âAmateurism meant back then that the athlete had to turn a blind eye to everything that was going on in society,â Gladwell said. âTo this group of guys, Carlos and Smith and Harry Edwards, that just made no sense. ⌠Youâre supposed to go to the Olympic Games, perform in front of the world, and all of a sudden youâre not supposed to talk about what it means to be a Black person in America?â

Smith and Carlos rejected this. Edwards, a discus thrower at San Jose State in the â60s, was the architect behind their Black power salute. Since then, heâs focused on advancing athlete activism and most recently mentored Colin Kaepernick.

Gladwellâs podcast comes at a time when athlete activism is on the rise. Dozens have followed the lead of Smith and Carlos. Dozens want to silence them. The IOC still has policies in place limiting athlete protest.

Before the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter stated that in âany Olympic sites, venues or other areas,â the committee will not allow âdemonstration or political, religious, or racial propaganda.â The rule has since been modified to grant athletes the opportunity to speak out during news conferences, mixed zones, interviews or ahead of competition. Last year, dozens of athletes and organizations signed an open letter calling to ban Rule 50.

ESPNâs âDream On,â the first â30 for 30â docu-series on womenâs sports, focuses on the U.S. womenâs basketball teamâs that spurred creation of the WNBA.

Smith and Carlos were expelled from the Games after Brundage threatened to ban the whole U.S. track and field team if they werenât removed. They faced criticism at home and received death threats.

Peter Norman, the Australian silver medalist, did not raise his fist, but he did wear a human rights badge in solidarity with the Americans. Australian Olympic authorities prevented him from competing in another Games, despite his making qualifying times in 1972.

âItâs a tiny example of just how much depth and complexity and complication there is in that picture,â Gladwell said.

Gladwell said he doesnât understand why anyone could react so negatively to an athlete giving up their glory to speak out against injustice.

âThere remains this kind of extraordinary fear at what protest does to Americaâs sense of themselves,â Gladwell said. âWhy should someone reaching outside of themselves to talk about a much more important topic of how society treats its own, why should that make us fearful or angry?â

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.