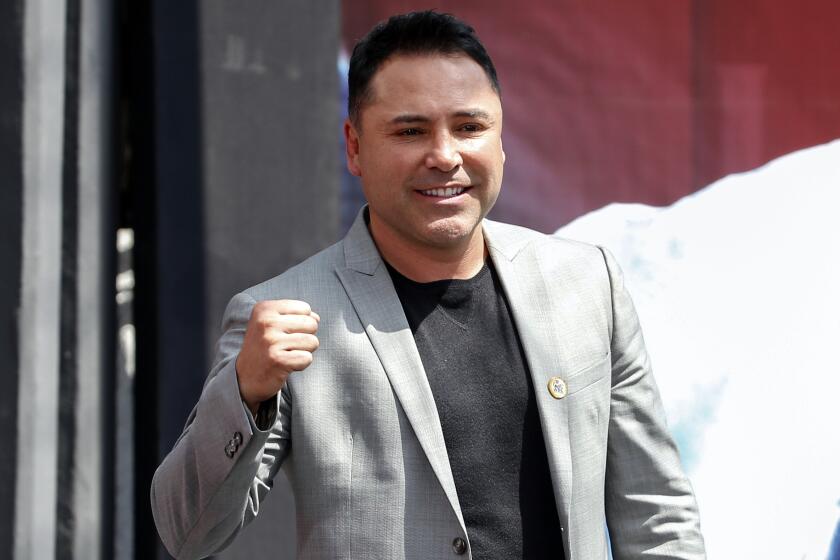

Column: Oscar De La Hoya is back on the defensive following latest sex scandal

Oscar De La Hoya nodded as he was asked about the sexual assault allegations made against him last week.

âLook, Iâm here,â he said. âI have nothing to hide.â

The former boxing champion removed his sunglasses, revealing stitches on his lower eyelids from a recent cosmetic procedure.

âI actually just got surgery, so, as you know, I should be staying at home,â De La Hoya said. âBut I have to keep young for my girlfriend.â

He joked that his girlfriend is fond of Gilberto Ramirez, the handsome light-heavyweight contender whose upcoming fight he is promoting.

De La Hoya returned to the subject of the question.

âBut I canât comment on it now,â he said.

What a dark turn this fairy tale has taken.

De La Hoya was the Golden Boy, his story the East L.A. version of the American Dream.

In a lawsuit filed Wednesday, a woman says former boxing champion Oscar De La Hoya sexually assaulted her during and after a company trip to Mexico.

He was positioned to be a Mexican American Magic Johnson, a beloved Los Angeles athlete who in retirement became a respected entrepreneur.

Instead, at 49, De La Hoya is a spectacle.

He became the subject of another scandal last week when he was accused of two instances of sexual assault in a countersuit filed by a woman against him and his tequila company.

The company, Casa Mexico, filed a civil lawsuit in December against the woman and another former executive, accusing them of breach of fiduciary duty and breach of contract.

De La Hoya denied the sexual assault allegations in a statement released by his boxing promotions company.

This column isnât the place to litigate the accusations made by either side. The courts will decide who did what.

However, whatâs beyond dispute is how De La Hoyaâs out-of-the-ring reputation has been shaped by a series of scandals.

De La Hoya was accused of raping a 15-year-old girl in a Cabo San Lucas hotel room in 1996. The resulting lawsuit was settled out of court.

A San Bernardino woman filed a lawsuit against him in 2019, claiming he sexually assaulted her two years earlier. The case was dismissed in 2020; the court docket didnât indicate whether a settlement was reached.

De La Hoya was arrested in 2017 for suspicion of driving under the influence of alcohol. De La Hoya failed field sobriety tests but the charges were later dropped.

His problems with drugs and alcohol are well documented.

He has still enjoyed a measure of success in the boardroom. His decision as an active fighter to break with promoter Bob Arum and take greater control of his career became a roadmap followed by the likes of Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Canelo Ălvarez. He purchased a controlling share of a downtown Los Angeles office building in which his promotions company is headquartered.

But these achievements have been overshadowed by the image of De La Hoya as dysfunctional, someone with credibility problems who will say whatever he has to to charm his audience.

Which is a shame, considering the opportunity that was presented to him.

De La Hoya was in the right place at the right time. By the time he won an Olympic gold medal in 1992, Fernando Valenzuelaâs fans were having children. These children were multicultural and often multilingual. They saw a part of themselves in De La Hoya.

Good-looking, well-spoken and nonthreatening on the surface, De La Hoya also was accepted by white people in a way that, say, Fernando Vargas never could be. De La Hoya had a chance to be more than a fighter, and for a while, he was.

World heavyweight champion Tyson Fury retained his WBC title with a sixth-round stoppage of fellow Briton Dillian Whyte in front of more than 94,000.

He could have been an enduring source of pride for a once-marginalized community, a symbol of success in multiple fields.

Now, at best, heâs someone who is viewed with pity; at worst, with derision.

Maybe thereâs something in him thatâs broken and canât be fixed. He spoke in the fall about how he was sexually abused, how he lost his virginity to a woman in her late 30s when he was 13.

De La Hoya wonât end up like Los Angeles boxing legends of previous eras, such as Mando Ramos and Bobby Chacon. His wealth protects him from that kind of tragedy. But De La Hoya isnât Magic Johnson, either. His tragedy is of another variety.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.