John Biever shot first game in 1967 at age 15; he’ll shoot No. 56 on Sunday in Inglewood when Rams play Bengals

- Share via

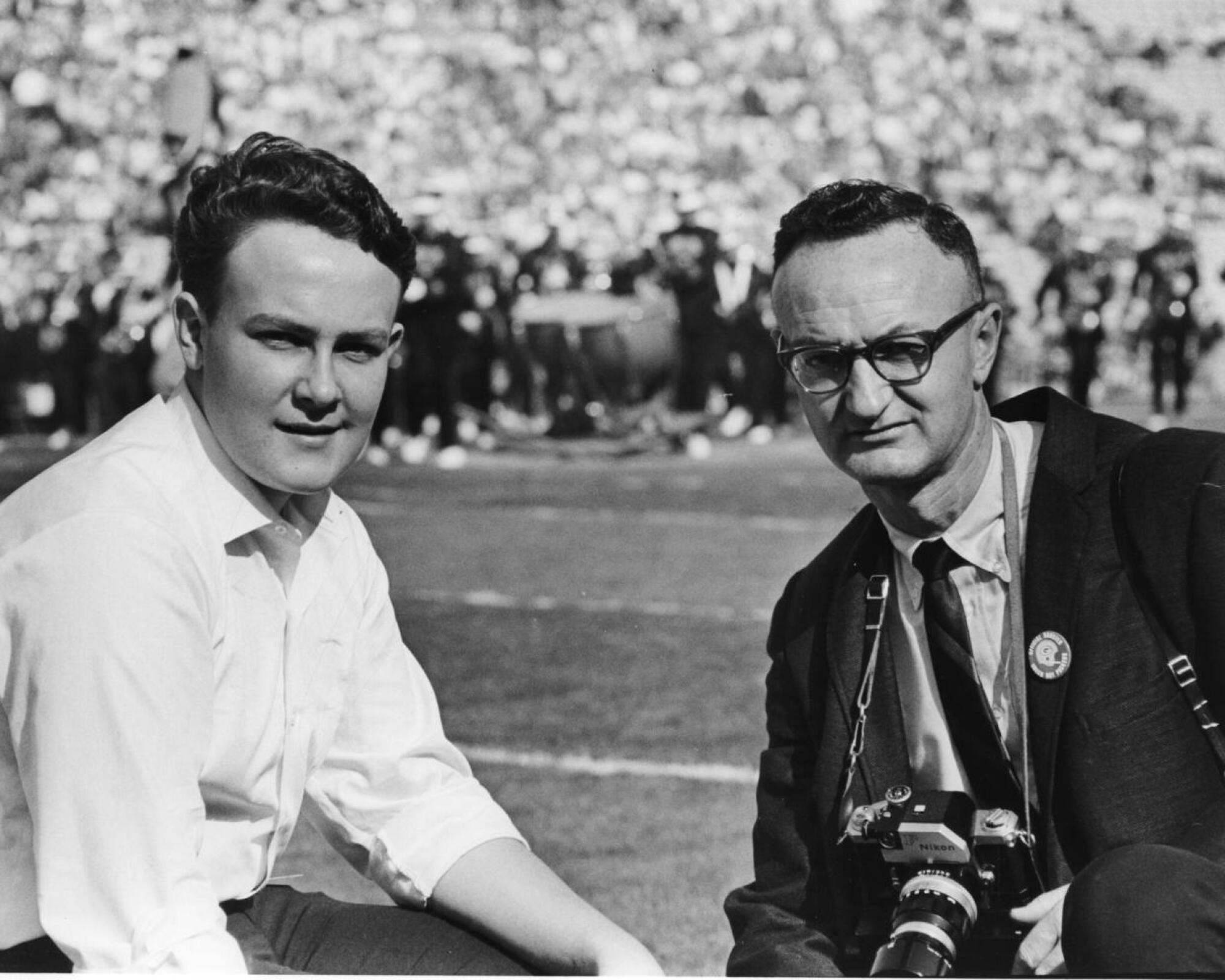

While his teenage friends were inside huddled around a television set watching football’s biggest game on a freezing Wisconsin day in 1967, John Biever was on the uncrowded sidelines of the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum on a warm, sunny afternoon, photographing the first Super Bowl with his father, Vernon.

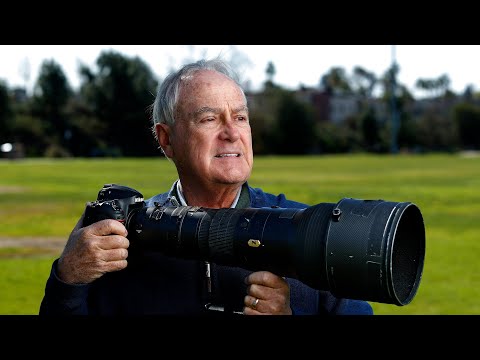

This Sunday, Biever, now 70 and a San Diego resident for the past decade, will be in a familiar spot. He will be photographing the Cincinnati Bengals playing the Los Angeles Rams in the Super Bowl at Sofi Stadium, just seven miles and a lifetime of images away from that initial game at the Coliseum.

It’s the 56th Super Bowl — for the NFL and for Biever, who is the only person to photograph every Super Bowl. Biever has seen it all, from Green Bay Packers coach Vince Lombardi in the first game to last year’s Super Bowl MVP Tom Brady and everything in between.

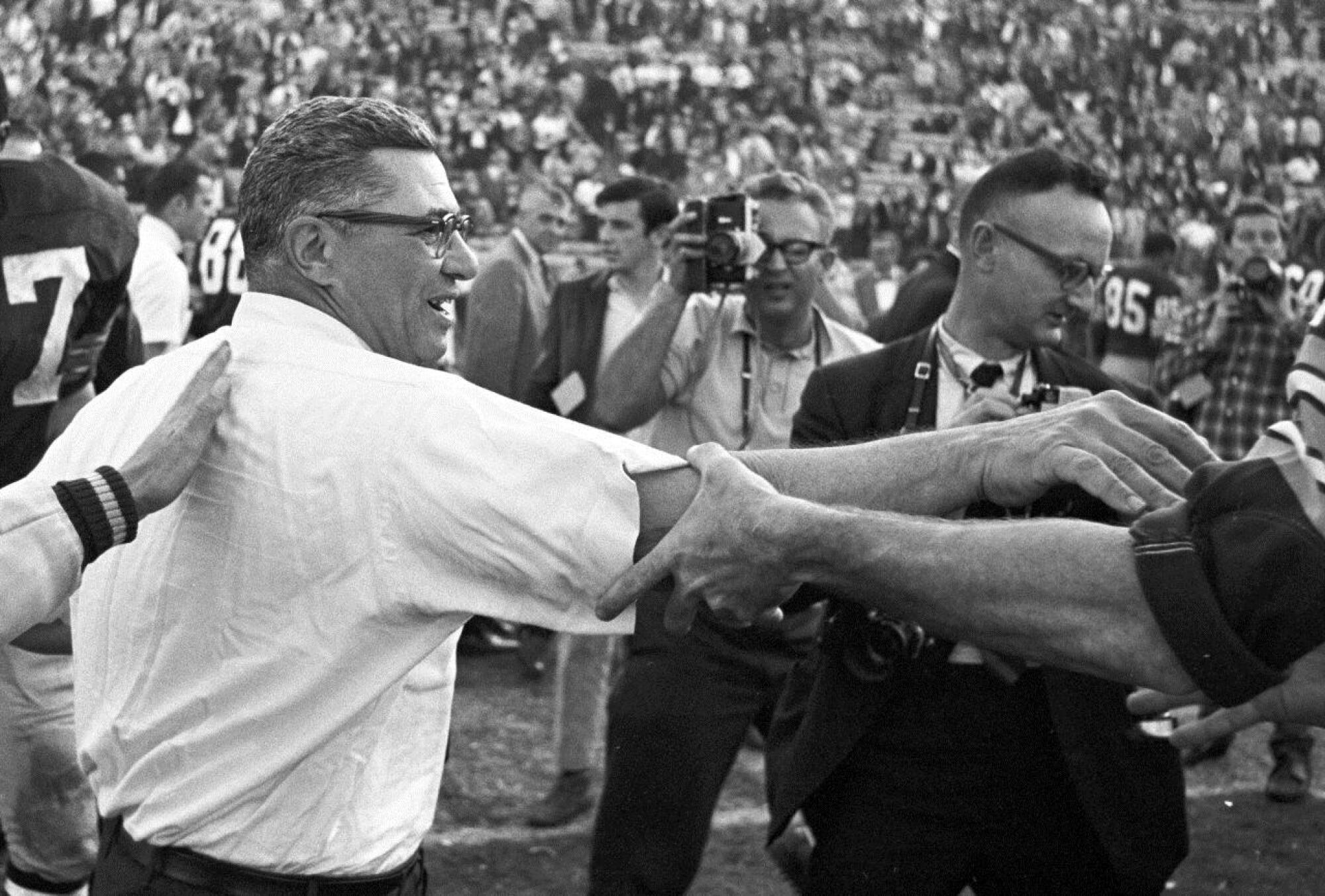

Growing up in the Milwaukee suburb of Port Washington, Wis., Biever became interested in his father’s side gig of sports photography. After serving in the Army in World War II, Vernon Biever would spend weekends as the Packers’ official sideline photographer. As a teenager, Biever started tagging along with his dad to games. His father would hand him a camera and a few rolls of film, and he was free to roam around the sidelines and even the locker room. It came with one rule: Don’t get in the way of Lombardi.

Biever distinctly remembers his first NFL game. It was the NFL championship in January 1966 at Lambeau Field and turned out to be legendary running back Jim Brown’s last game for the Cleveland Browns. One of Biever’s photos ran in Look magazine and his dad realized he had some talent. He was 14 at the time.

John Biever shot the first Super Bowl in 1967 at age 15; he’ll shoot No. 56 on Sunday in Inglewood when Rams play Bengals.

After doing regular season games the next season, his dad invited him to the AFL-NFL World Championship Game in Los Angeles, which later would be known as Super Bowl I. The NFL’s biggest game hadn’t yet taken center stage in the country, but it was an opportunity to kick-start a legendary photography career.

“Amazingly, it was not very crowded and the sidelines were not busy at all. Bob Hope was next to me for a while,” Biever remembered. “Wow, what’s going on here?” he thought to himself. “It was pretty exciting stuff.”

One classic color photo he took from that game was of the Super Bowl’s first touchdown, a 37-yard reception by Green Bay’s Max McGee from quarterback Bart Starr, taken with a 35mm Nikon camera with a 135mm lens. The photo was not only a part of history, but it looked like a Norman Rockwell painting. McGee’s gold pants and gold helmet with a single-bar facemask were illuminated by the early afternoon sunlight as he ran on the natural grass into the end zone with an official in tow. In the background, a row of cheerleaders looked on along with fans in short sleeves, some wearing ties, as well as rows of empty seats with not an advertisement in sight.

It was a great start for Biever, but his all-time favorite photograph came after the game ended. After the Packers beat the Chiefs 35-10, Biever made a black-and-white frame of a smiling Lombardi reaching out in celebration during the postgame scrum on the field. In the background, on the right side of the wide-angle shot, was his father. “Having those two together in the photo was important to me,” he said.

Biever was now a Super Bowl veteran at the age of 15.

Two years later his Super Bowl streak would be in jeopardy. His father was able to get him into the first two Super Bowls because the Packers were playing, but had a hard time with the game between the Jets and Colts in Miami. Biever was sitting in a high school class a few days before the Super Bowl when it was announced over the school intercom, “John Biever, please report to the office and bring your materials with you.” Biever thought he was in trouble, but his father had arranged for a neighbor to drive him to the airport to head to the game.

Family friend Steve Sabol, who ran NFL Films, secured Biever a credential after hearing he wasn’t going to make it. It turned into a regular gig. He worked the next few for NFL Films and later for NFL Properties, the merchandising and licensing arm of the league through Super Bowl XIX. High school and college classmates would pepper him with questions when he would return from these trips.

Biever graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and then worked as a photographer for his hometown newspaper, The Milwaukee Sentinel, and the afternoon Milwaukee Journal. He photographed regular newspaper assignments but relished photographing sports and politics, which he says are very similar with decisive moments.

Wanting to expand his horizons, Biever began sending his newspaper clips to Sports Illustrated. Enough freelance work with the magazine allowed him to leave the newspaper after 13 years. He became a contract photographer for Sports Illustrated and eventually a staff photographer, shooting Super Bowls XX through 50 during his three decades with the magazine.

Biever would zigzag the country shooting action photos of A-list sporting events 250 days a year for SI. Ten Olympics, 24 Masters golf tournaments, countless World Series, NBA Finals, Final Fours and thousands of regular-season sporting events that led to his 132 Sports Illustrated covers. He would photograph a college and a pro football game every weekend.

Still, it was the Super Bowl that was more special than the others. Biever got to spend Super Bowl weekend shooting photos alongside his dad for the first 35 of them. Biever’s brother Jim took over as the Packers’ team photographer for their father as he got older, and the three of them would get to work together at a number of games.

Among Biever’s colleagues at Sports Illustrated was famed sports photographer Walter Iooss Jr., whose work Biever admired growing up. “He was the best ever,” Biever said of Iooss. “I saw his pictures of big events, and that’s what I wanted to do.”

Iooss, like Biever, started shooting the NFL as a teenager and was also part of a small group of photographers who shot every Super Bowl for five decades until he missed it last year due to the pandemic. “John was always a great photographer. He’s the last man standing for the streak and good for him,” Iooss said from his home in Florida.

The two would often be on opposite sides of the country shooting assignments, or on the opposite sides of the field at the same event, but always had the Super Bowl connection.

“Part of being a good photographer is to know the game, and that was genetic with him. John knowing the game, he took great photos of football,” Iooss said.

On the eve of the 50th Super Bowl, the two were honored by the NFL along with the few other photographers and writers who had covered every game. The league flew them and a spouse to the game in Santa Clara and also gave them a pair of tickets.

As the NFL grew in popularity through the years, Super Bowls became big productions. Unlike the early years, where the games would be played on natural grass and in the afternoon sunlight, modern games are later in the day, often played on artificial turf and almost all under artificial light, not making for the best photos. News organizations would send a small army of photographers to cover Super Bowls. Sports Illustrated would send a dozen photographers, each assigned a stationary spot on the field and around the stadium.

For the photographers in this situation, the quality of photos often depended on the luck of the draw of where the action on the field took place. Manual-focus film cameras would eventually be replaced by high-resolution digital cameras with foolproof autofocus, giant telephoto lenses and unlimited digital storage. Long gone were the days of changing rolls of film as fast as you could in between big plays.

“The best photos always were the ones with the play right in front of you taken with your wide-angle lens,” Biever said.

Photographers’ memories of big games often relate to how good their photos turned out and rarely the score or who was playing the halftime show.

For this year’s game, the strategy is simple: “I’m looking to not miss the best play because if you do you have a year to think about that.”

Biever had great experiences at San Diego’s three Super Bowls. In 1988, he had the cover of the magazine with the game’s MVP, Redskins quarterback Doug Williams, but also a two-page spread of Williams grimacing as his knee twisted early in the game. In 2003, he had the cover again, this time of the Buccaneers’ Joe Jurevicius stiff-arming a Raiders player at Qualcomm Stadium. The 2003 game was the magazine’s first all-digital photography Super Bowl.

When asked to pick his favorite game he responded, “It’s the Super Bowl. They all have their own storyline.”

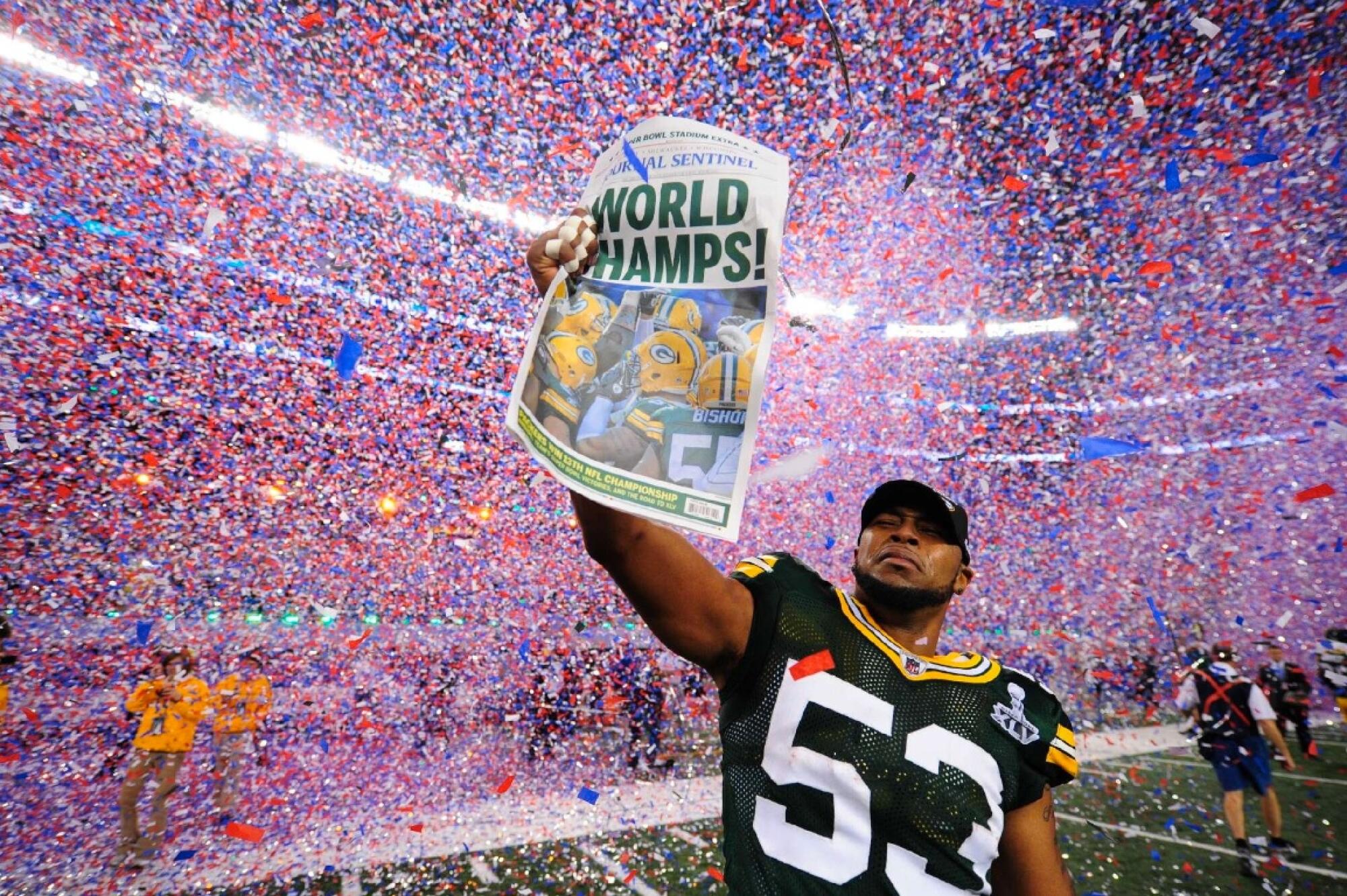

Another photo that stands out to him is one of Green Bay Packers linebacker Diyral Briggs, shrouded in confetti holding a preprinted newspaper with the headline “WORLD CHAMPS” after the 2011 Super Bowl in Texas. While other photographers were chasing around the game’s MVP, quarterback Aaron Rodgers, Biever made this quiet frame of Briggs holding up The Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, his former newspaper. His team winning, his old newspaper and a double-page spread in the magazine of the photo is the one that stirs an emotional connection for Biever.

In 2012, Biever took a buyout from Sports Illustrated but continued to do occasional assignments. The next year he moved to San Diego and later married his longtime assistant Deb Finnegan. “It wasn’t a hard sell moving from Wisconsin to San Diego,” he said.

To commemorate the NFL’s 100th season in 2019, a panel of the top photographers and photo editors selected the 100 greatest NFL pictures. More than a handful have the Biever name on them. Biever, his brother and his dad were all included. “It is special to have all three of us in there. My dad had some classics.”

Part of Sunday will be much like the first Super Bowl, with a beautiful Los Angeles day and temperatures in the mid-80s. But the game will be played on artificial turf and under artificial lights in a covered stadium. Missing will be the uniforms covered in dirt or shadows crossing the field, things that often make a good photograph great. But one thing will be the same: Biever, who will be working for NFL Photos, will have his cache of Nikons, scouring the field hoping to capture the play of the game.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.