- Share via

Feeling buoyant from his Oxnard High graduation ceremony and dinner with his mom and girlfriend, Denver Clayton Lemaster — everyone called him Denny — turned onto his narrow street and let out a nervous chuckle. Cars lined the curb, and about a dozen men stood in his driveway.

“Oh, my,” his mother said from the back seat. “What’s all this?”

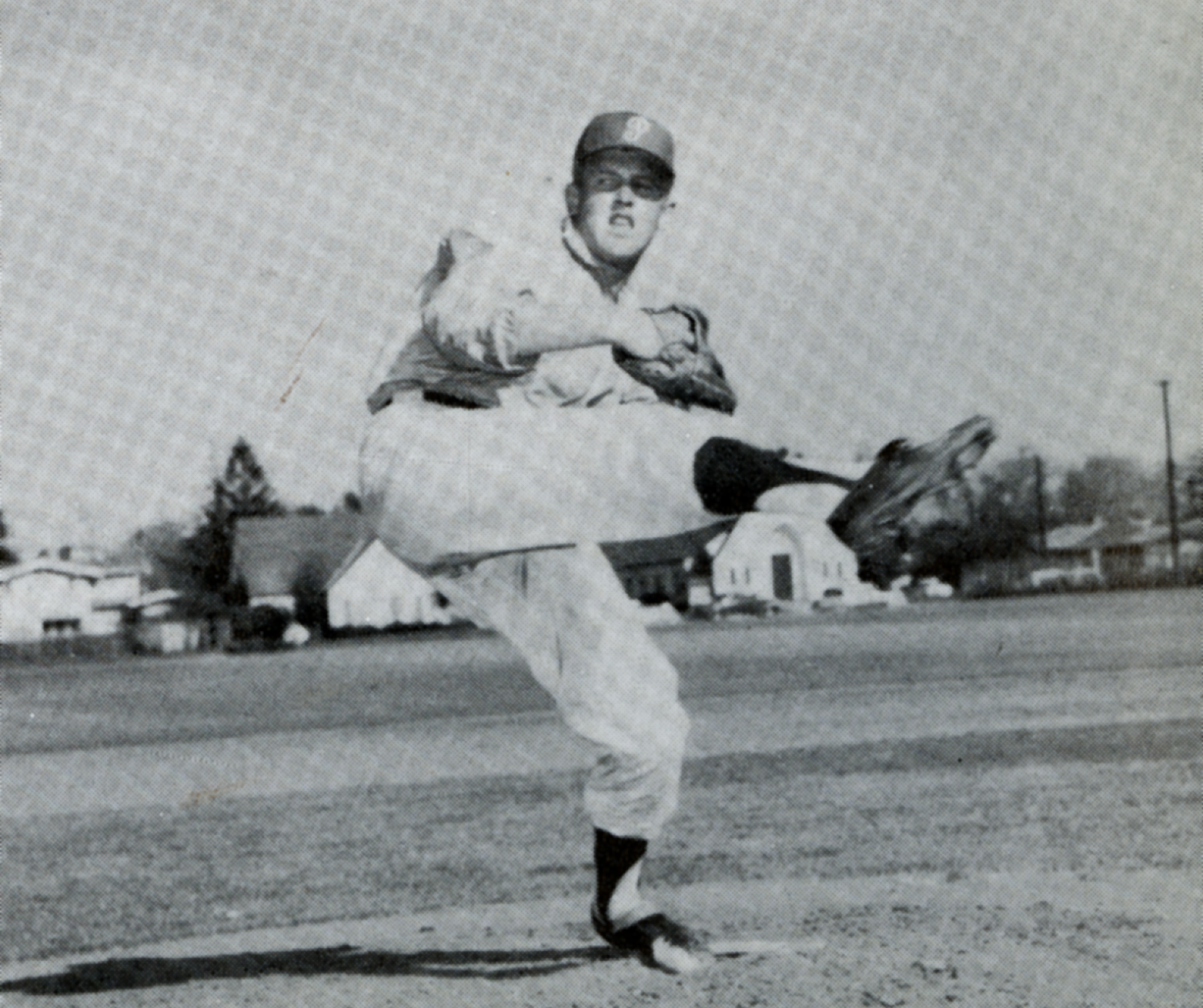

The men were major league baseball scouts jockeying to shovel more money to Denny than he’d ever imagined. The year was 1958, a major league baseball draft had yet to be implemented, and prospects could sign with any team upon graduating high school. Denny, a left-handed pitcher with an explosive fastball and knee-buckling curve, was the subject of a bidding war.

The Lemasters invited the scouts into their home and politely asked them to line up in an orderly fashion. One after another they made their pitch.

“You’ve got a country mother who didn’t know anything about baseball and the son who just turned 19 bargaining with these guys, and this is all they do,” Denny says today.

He knew enough to use a scholarship offer from USC as leverage and signed with the Milwaukee Braves for an $80,000 bonus, about $769,000 today. Within days he’d catapulted out of Ventura County and launched a 15-year professional career that by 1962 would make him a teammate of future Hall of Famers Warren Spahn, Hank Aaron, Joe Torre and Eddie Mathews.

That same June evening, six-year-old Baudelio Salinas Jr. — everyone called him Buddy — lay awake in the two-bedroom, one-bathroom Oxnard house he shared with his parents and seven brothers and sisters.

Buddy dreamed big, and he dreamed about baseball, taking the pitcher’s mound and mowing down hitters like his idol, Denny Lemaster. He became a star Little League pitcher, shutout after shutout chronicled on the same Oxnard Press-Courier sports pages that described Lemaster’s exploits with the Braves and, eventually, the Houston Astros. But when it came time to try out for the Oxnard High team, Buddy, all of 5 feet 4, was cut.

His love of baseball and admiration for Lemaster never wavered. Buddy married his high school sweetheart, Mitzi, launched a plumbing business and plunged into the community, a gregarious man who seemingly knew everyone in Oxnard and could recite tidbits about every top athlete in town.

On Feb. 13, 1980, at a job two blocks from his own home, Buddy climbed high into a bedroom closet to fit pipe and noticed a baseball tucked in the far corner of a shelf. Names were signed all over the ball. He spun it in his hand and brought it to the owner of the house, John Milani, who said, go ahead, Buddy, you can have it.

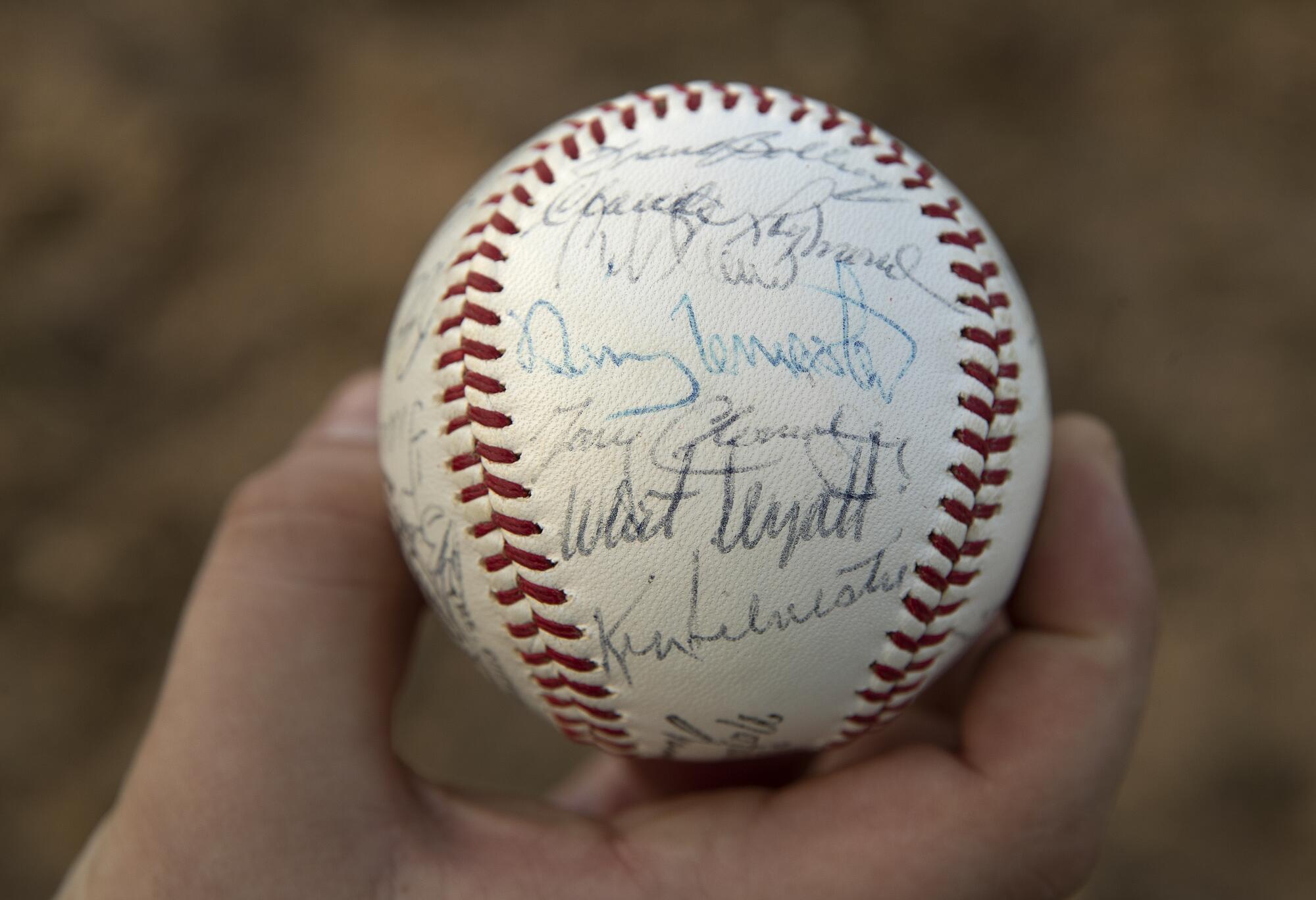

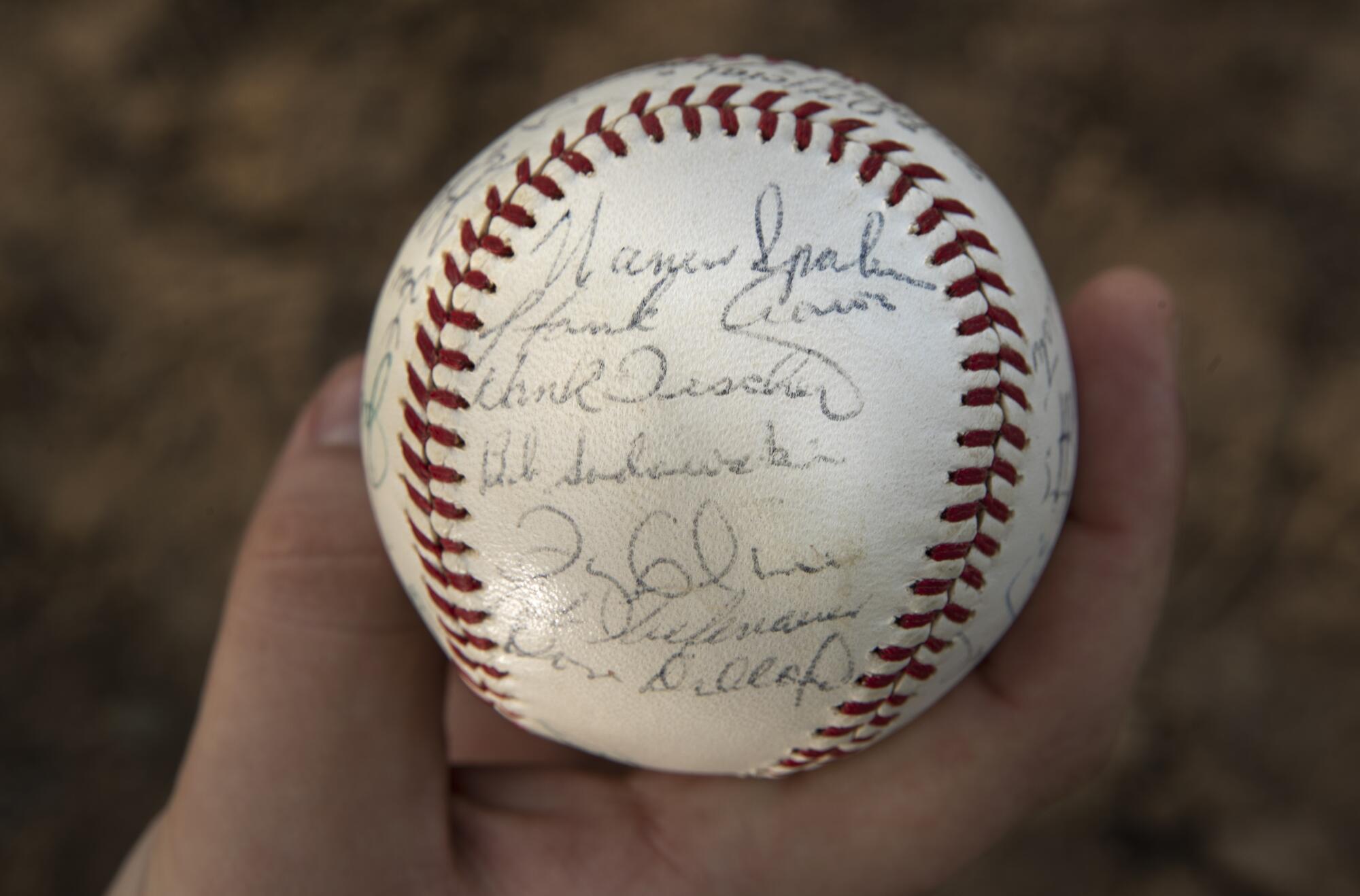

He examined the ball carefully when he got home. The signatures were from Milwaukee Braves players in 1963. In the practiced penmanship of the era, the names Spahn, Aaron, Torre and Mathews jumped out.

Buddy slowly turned the ball. Lew Burdette, Bob Uecker . . .

There it was! In cursive and blue ink: Denny Lemaster.

Buddy bought a protective case for the ball and placed it in a safe — a connection to the pitcher he’d idolized but never met, the major leaguer he never became.

::

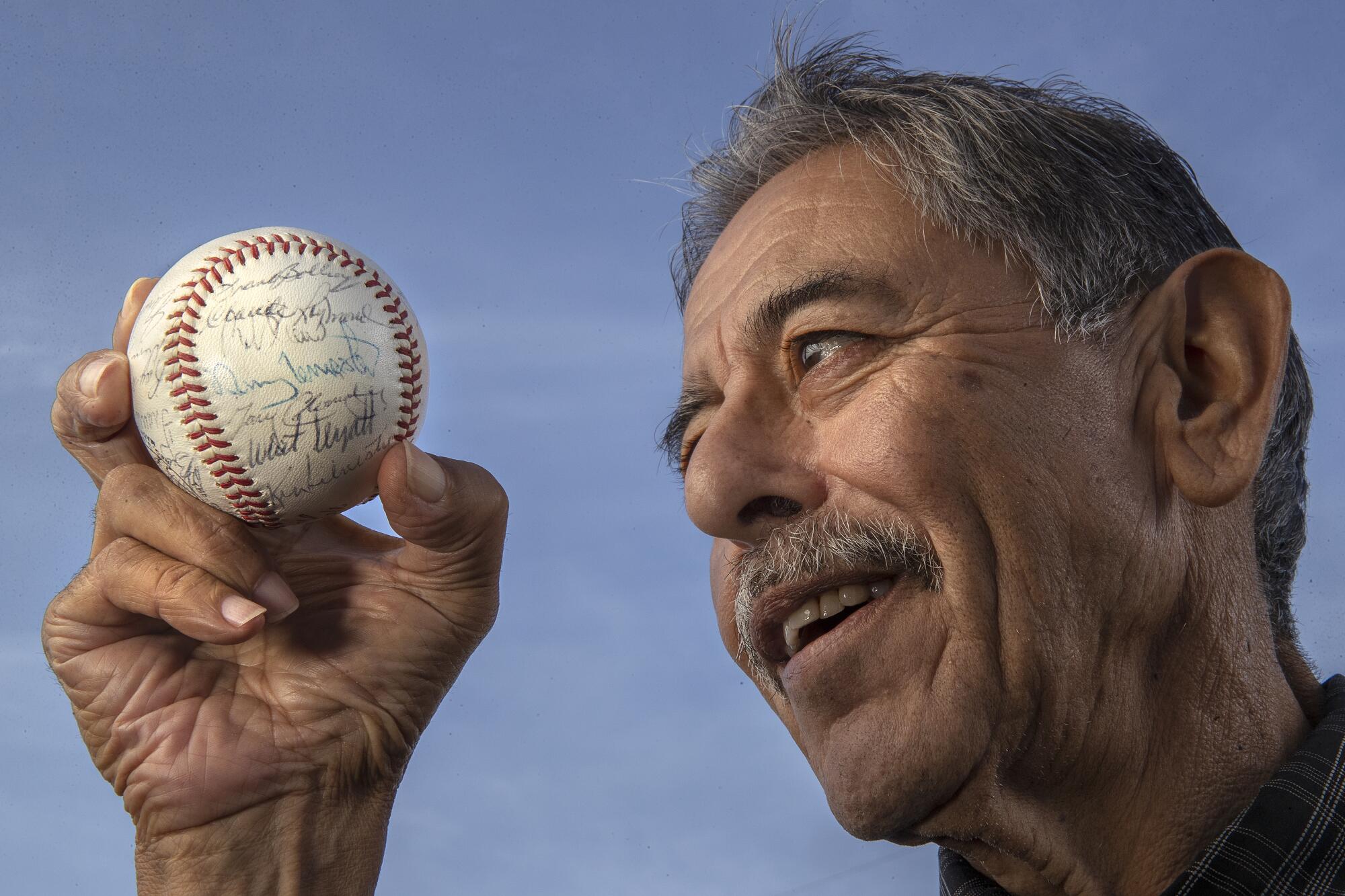

A thought struck Buddy, now 69, while he was in hospice 18 months ago. Doctors told him he had only days to live. The baseball, the one he’d locked away for so long, ought to be returned to its original owner.

He recovered enough from the problems with his liver, kidneys and bladder to move out of hospice and regain his mobility. It was something of a miracle that he was alive to watch the Atlanta Braves win the World Series this past fall. And the thought struck again.

Buddy walked to the kitchen the next morning and set the ball on the table. “I’m going to find Denny Lemaster and give this to him,” he told Mitzi, who was initially incredulous.

“Give the ball to your grandson,” she replied. “It can help pay for school.”

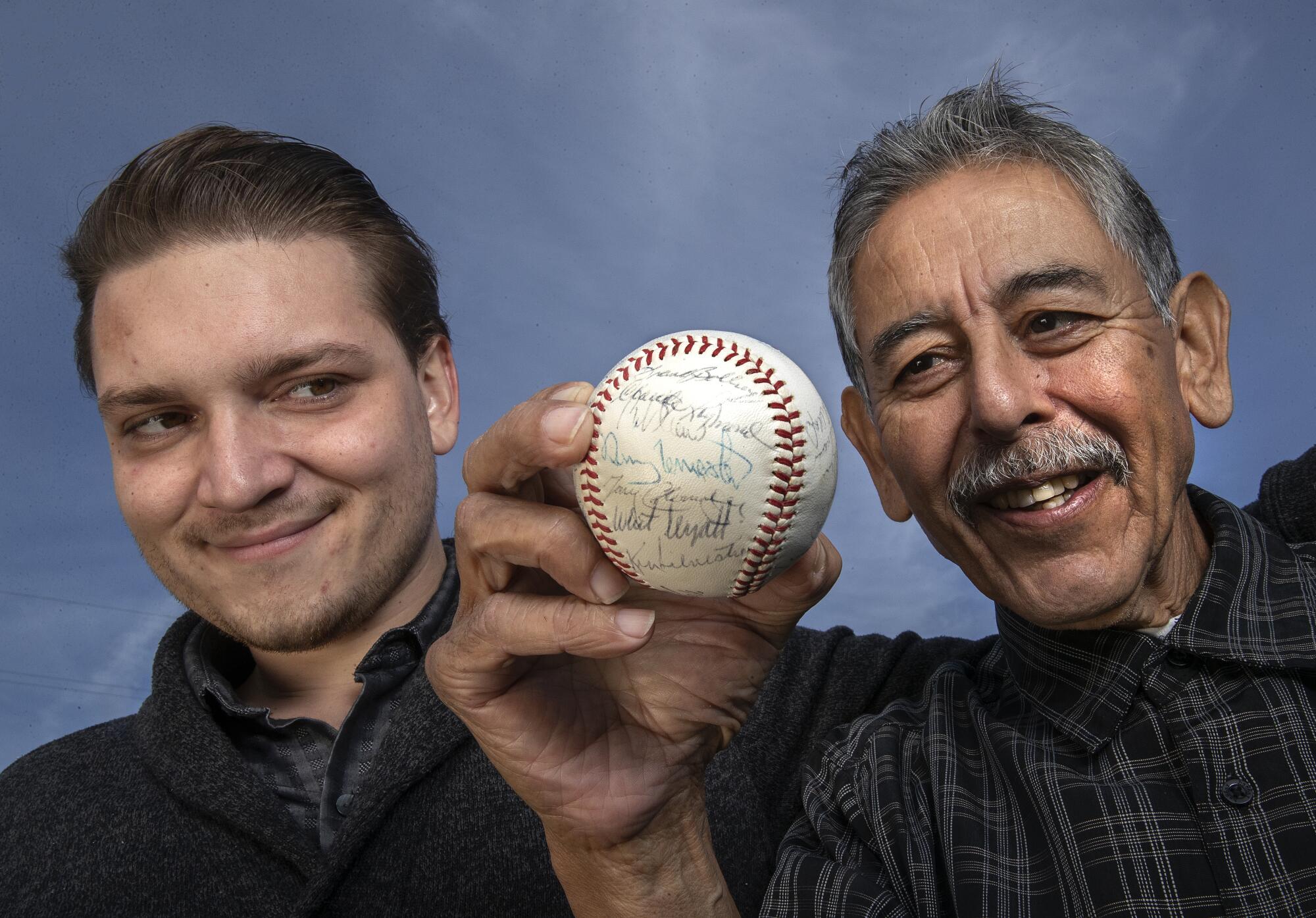

Alec Salinas, a criminal justice major at Ventura College, looked up from his breakfast. “Grandpa gets to do what he wants with that ball. I’ll be fine.”

So Buddy, equipped with an iPad and an internet-savvy grandson, set out to locate Denny. But emails and phone calls to the Braves weren’t returned. Friends and relatives were either deceased or unreachable.

“It seemed like everyone thought I was a crazy old man,” Buddy says.

The Society of Baseball Research was the only email recipient to respond immediately, saying it would be glad to accept the ball. Buddy scoffed. All that mattered to him was reaching Denny.

“I just want him to know the man was loved in Oxnard,” Buddy says. “People in Oxnard never forgot you and we love you. Period.

“Oxnard means a lot to him. I know it does.”

::

Denny, 82, lives comfortably near Atlanta with his second wife, Bunny. Many of his seven children live nearby, as do a couple dozen of his 39 grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

When he retired from baseball in 1972, he worked as a fishing and hunting guide, then surprised his family by revealing an artistic side, carving and painting wooden duck decoys that won awards and sold well for many years.

He enjoys reminiscing, even though his life was interrupted more than once by unspeakable tragedy.

Denny moved to Ventura County at age 7. World War II had just ended, and his father, Cyrus Lemaster, yearned for the prosperity he heard was plentiful in California. Cyrus had quit school in the fourth grade, but his hands were strong as vice grips from milking cows for years on farms near Springfield, Mo.

A friend called and said Cyrus had a job waiting at Adohr Farms milk dairy if he could make it out to Camarillo. Cyrus loaded his belongings in the cargo bed of a 1937 Ford pickup, squeezed his wife, Mildred, Denny, daughter Lana and the family cat into the front seat and headed west.

Adohr housed the Lemasters on the dairy property for $31 a month. Mildred found work as a nurse, and Denny became curious about a game the children of dairy workers played in an open field near his house.

“What are they doing?” Denny asked a neighbor. The man chuckled. “Playing baseball.” He told Denny to wait there and came back with a glove.

Denny knew enough to keep his left hand free to grip a ball and throw it. He slipped the glove on his right hand and the man said, “Wrong hand.”

“I’ll make it work.”

The man smiled. “It’s yours. Just don’t leave it out in the rain.”

Denny wore the wrong-handed glove until his parents bought him a three-fingered left-hander’s glove from Sears for his ninth birthday. He and Lana spent afternoons outdoors playing while their parents were at work, and he’d spend hours throwing rocks at fence posts.

Lana was skipping through the courtyard on dairy property near the Pleasant Valley Baptist Church one day in June 1951 when the ground beneath her gave way, swallowing her into a cesspool of raw sewage 35 feet below. Denny dashed to find neighbors to help, but it was too late.

A service was held, but the Lemasters didn’t contact a lawyer. Within a few days, the adults went back to work and Denny was back on the ballfield.

“We were just poor, uneducated people,” Denny says. “If that happened today, we’d have owned Adohr Farms.”

Three years later, tragedy struck again. Denny had just started high school and was walking home in downtown Oxnard, peering into storefront windows, when a woman told him his dad had been in a car accident.

Denny sprinted to St. John’s Hospital. A nun took him into a room and said Cyrus Lemaster was dead.

“Bluntly, that was a kick in the ass right there,” Denny says. “My dad was a huge baseball fan. He could recite the entire roster of the Brooklyn Dodgers. The one thing he wanted me to do was play baseball. I had one big determination from then on.”

Denny easily could have spun out of control, but the close-knit Oxnard and Camarillo communities rallied around him and his mom.

He and his best friend, Donnie Chase, often hitchhiked home to Camarillo from Oxnard High and were always picked up by a familiar face. They’d be let off at the dairy property where fresh food from the fields of Oxnard fed the families of workers.

“It was a cookout every night,” Denny says. “I can still smell those meals today.”

One quiet evening, Denny took his mom aside and said he’d never do anything to embarrass her.

“That was my motto in high school,” Denny says. “You can get into a lot of things at that age. When I’d see somebody get out of control, I’d pick up and leave. That became my routine.”

::

Buddy Salinas had his own routine by the time he turned eight: Bolt to the Little League fields by 7 a.m. and don’t return home until dusk. Oxnard Little Leaguers played at Durley Park, a block from the tiny house on Cedar Street where those seven brothers and sisters of his, loving as they were, jostled for bathroom time and crowded around the refrigerator.

“Food was there when it was,” Buddy says.

Durley Park had bathrooms — no jostling — and a snack bar. Best of all, it had baseball on four fields all day long. He learned to spin the ball just right, throwing a curve for strikes before most kids could even find the plate.

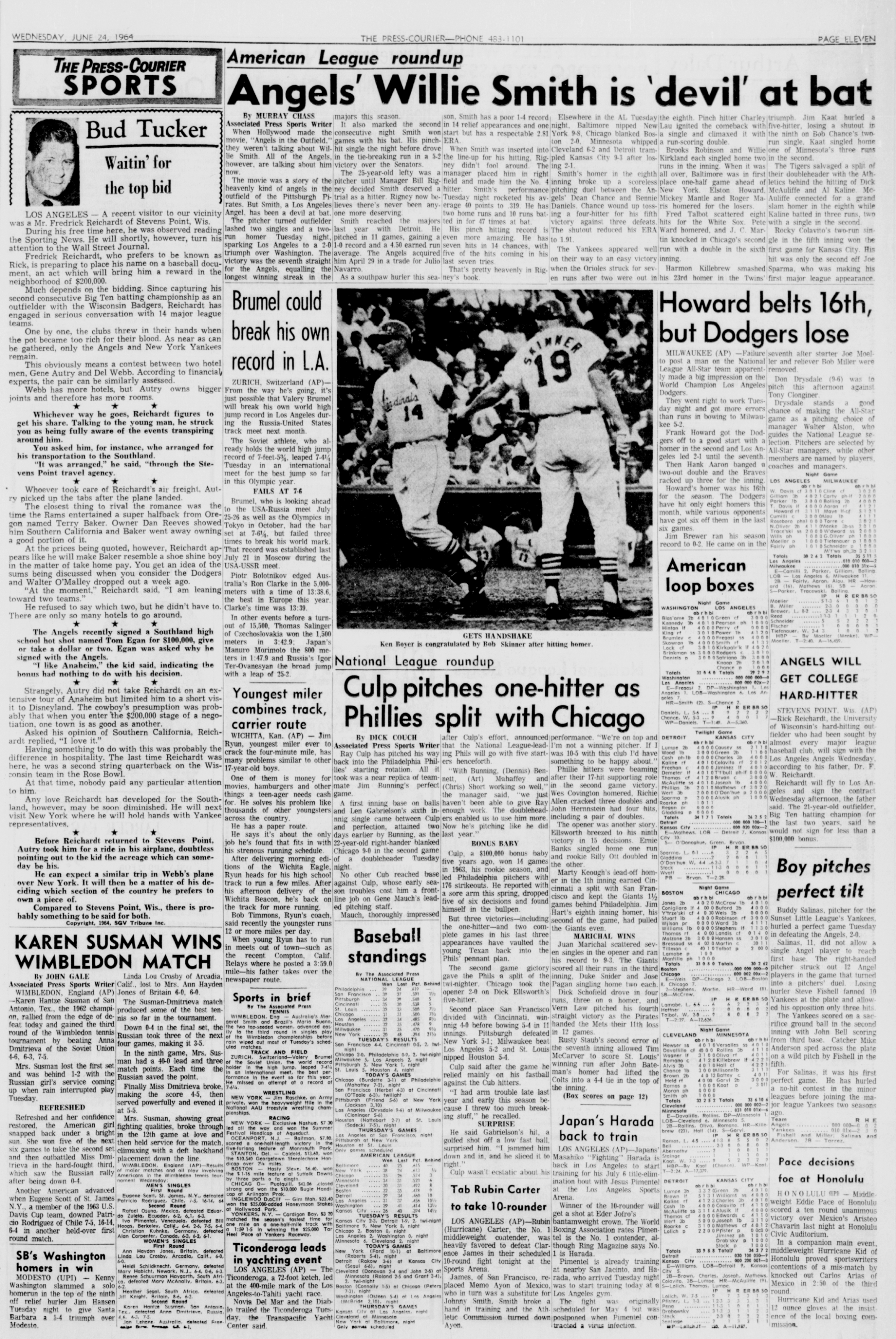

Barely 5 feet 2 at age 11, Buddy was the most effective pitcher in the league. He pitched a perfect game June 23, 1964, and afterward the admiring opposing coach bought him lunch at the snack bar. The next morning, the Oxnard Press-Courier blared the headline: “Boy Pitches Perfect Tilt.”

Buddy read the sports page curled up on his corner of the shared bed. He closed his eyes and allowed himself to dream of pitching at Dodger Stadium, of being a major league All-Star, dreams that seemed possible because they’d come true for Oxnard’s own Denny Lemaster.

Buddy was a Little League all-star five years in a row. He won county-wide Yo-Yo competition while in middle school. He developed a knack for setting a goal and achieving it — and has done so throughout his life.

When his daughter, Robbie, turned 21, Buddy hatched an idea: Have entertainer Wayne Newton call Robbie at the party he was throwing for her in Las Vegas.

Buddy rented a limo, drove to Newton’s Casa de Shenandoah compound and spoke into the intercom: “Mr. Newton, I know you have a daughter, and I’m here with my daughter for her 21st birthday. She is so important in my life. Would you please call her if I give you the number and time we are at dinner?”

That night at the Horseshoe Steakhouse, the maitre d’ just laughed when Buddy asked him to place a telephone on his table because Wayne Newton was going to call. At the appointed time, the restaurant phone rang, and the stunned maitre d’ answered and handed the phone to Robbie Salinas.

“Robbie, this is Wayne Newton. Happy birthday!” That night, Buddy and Robbie attended Newton’s show and Newton dedicated a song to her.

::

The left-hander Buddy saw pitch at Oxnard High was one of the most dominant pitchers in Southland history. Denny threw seven no-hitters, including a perfect game. His earned-run average for the 1958 season was 0.14.

Little League hadn’t taken hold in Ventura County when Denny was a youngster. The first organized baseball he played was on a men’s semipro team called the Camarillo Blue Sox. He started off as a bat boy before joining the team as a first baseman at age 14.

Shortly after Cyrus Lemaster died, the manager of the team, Demetrio Ayala, told Denny he wanted him to pitch every Sunday during the summer and fall when the games drew the most attendance. “These guys are married and have kids, and I’m not even 16,” Denny replied. “You sure?” Ayala smiled and nodded.

“In three years pitching for them, I only lost three games,” Denny says. “Every Sunday, Mr. Ayala would give me a big hug and stick a crisp $100 bill in my back pocket.”

Soon enough, it was the Milwaukee Braves sticking a check for $80,000 into his bank account. By 1962, he’d earned a place in the starting rotation. His most memorable game came Aug. 9, 1966, when, while pitching for the Atlanta Braves, he outdueled Sandy Koufax by taking a no-hitter into the eighth inning of a complete-game 2-1 victory in front of 52,269 fans, then the biggest crowd ever at Atlanta Stadium.

Every offseason, Denny would return to Oxnard and drive a truck for the same asphalt company that gave him his first job in high school. And one day after the 1963 season, he gave a signed ball to Milani, a friend and mentor who also worked at the asphalt company.

Tragedy struck again when Denny’s wife, Earlene, was killed in a car accident in the mid-1970s. Denny remarried in 1983, and today he and Bunny have their share of memorabilia from Denny’s career. What he didn’t have, however, was a certain ball signed by his entire team in 1963.

::

Funny how a baseball, meant to be hurled and spun and swatted upward of 100 mph, can produce connectivity after being motionless for decades.

Finally someone answered a call from Buddy: Denny’s son, Dennis, an electrician near Atlanta. He gave Buddy Denny’s phone number, and soon a conversation took place between two Oxnard fellows and baseball men.

“He is as nice as can be,” Buddy says. “He got mad at me because I kept calling him sir. You call me Denny, he said. You take as much time as you want. He wanted to keep talking. It was beautiful.”

Because of the signatures of the four Hall of Fame players, the ball would be worth about $500 to a collector. Buddy gauges its value differently.

“It’s priceless,” he says. “It will fit in Denny’s heart just right. When he grips it, I just want him to feel that ball and say, ‘Yes, I remember.’ ”

On Monday, Denny did just that, receiving the ball Buddy had mailed, signed, sealed and delivered. Memories came flooding back.

Of his high school teammate Ken McMullen, who broke into the majors with the Dodgers and played 16 years in the major leagues.

Of John Milani, Demetrio Ayala and everyone who supported his journey after the deaths of his sister, father and first wife.

Of the years with the Braves, befriending immortals Hank Aaron and Warren Spahn, funnyman Bob Uecker and Joe Torre, his catcher in 114 starts.

“I think about how many people were there for me along the way, and I really have been blessed,” Denny says. “This Oxnard fellow, Buddy, went to great lengths to get me this baseball. I deeply appreciate that.”

The saga had played out the way Buddy envisioned. But it doesn’t appear he’s done.

“Oxnard doesn’t even have a Denny Lemaster Day,” he says. “That is a disgrace. He put Oxnard on the map. I’m going to have to work on that.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.