Commentary: MLB owners make their bargaining position clear: No

- Share via

As major league teams lavished close to $2 billion on players in the final days ahead of Wednesday night’s lockout, fans and analysts frantically searched for clues toward the resolution of baseball’s labor mess. Team owners were Oprah one day — a big fat contract for you, for you, for all of you! — and the Grinch the next. What does it all mean?

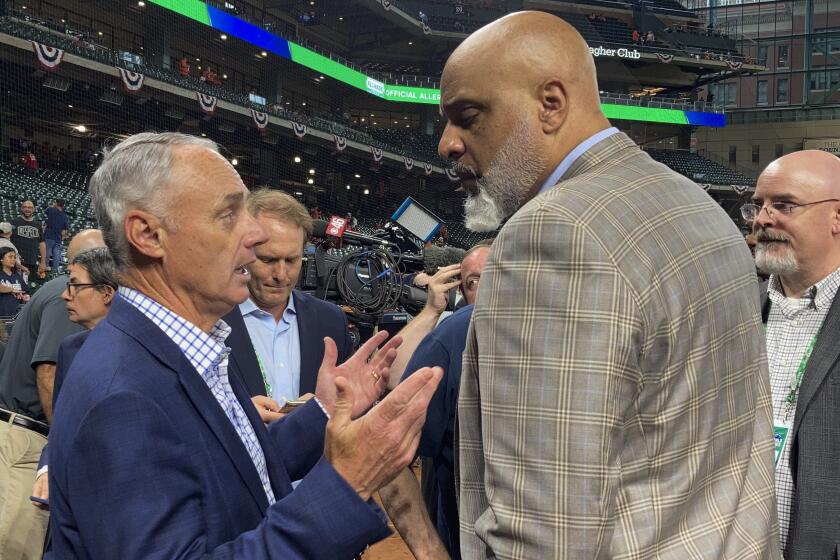

After Commissioner Rob Manfred and union chief Tony Clark staged news conferences Thursday, what it all means appears plain. The owners spent all that money on the premise that baseball’s economic system under the next collective bargaining agreement will look pretty much the same as it did under the old one.

The owners, at least, already have decided how the lockout will end. As the owners appear to see it, based on the news conferences from both sides, the players will back off on what they have prioritized as core issues, or the next major league game will take place a long, long time from now.

Since owners value younger players more than ever, the union argues, the owners should pay younger players better than ever: salary arbitration after two years instead of three; free agency after five years instead of six.

Bruce Meyer, the lead union negotiator, said the owners refuse to discuss those issues. Manfred, in his news conference, was not shy about saying why.

The collective bargaining agreement between MLB and the MLB Players Assn. expired without a new agreement in place, triggering a lockout.

“Bad for the sport, bad for the fans, and bad for competitive balance,” Manfred said.

Manfred focused on the proposal to let players hit free agency sooner.

“I think we already have teams in smaller markets that struggle to compete,” he said. “Shortening the period of time that they control players makes it even harder for them to compete.

“It’s also bad for fans in those markets. The most negative reaction we have is when a player leaves via free agency. … Making it available earlier, we don’t see that as a positive.”

The Dodgers have Mookie Betts because the Boston Red Sox did not want to pay him market value and traded him even before he could reach free agency.

Boston is not a small market. San Diego is, and the Padres committed $340 million to Fernando Tatis Jr. Milwaukee is, and the Brewers committed $215 million to Christian Yelich. Tampa Bay is, and the Rays committed $182 million to Wander Franco.

Kansas City is, and the Royals are the last American League team to make back-to-back World Series appearances.

That said, Manfred is not wrong when he says it is more difficult to win in smaller markets. The margin for error is smaller. For years, players told owners to resolve that problem among themselves, and the owners finally agreed to revenue sharing, where teams like the Dodgers subsidize teams like the Brewers.

That, no doubt, is why owners are livid that players now propose to cut the amount of revenue sharing.

“Taking $100 million away from teams that are already struggling to put a competitive product on the field, I don’t see how that’s helpful,” Manfred said.

The union is livid that teams like the Baltimore Orioles and Pittsburgh Pirates keep stuffing revenue sharing money into their coffers without any measurable improvement toward putting a competitive product on the field.

And, really, with 17 teams eligible to receive shared revenue, that budget cut of $100 million per year would average out to less than $6 million per team. If you really need that marginal a contribution, in an era when national broadcast revenue has soared and MLB is rapidly generating revenues for all its teams from sports betting and cryptocurrency, you probably shouldn’t be running a major league team in the first place.

It didn’t take long for MLB owners to impose a lockout once the collective bargaining agreement expired. It may take a long time before the game is played again.

Of all the proposals Manfred outlined Thursday, including increases in minimum salaries and the institution of an NBA-style draft lottery to reduce the incentive for teams to tank, he identified one as a “major concession.” That was an end to free-agency compensation, meaning the draft picks teams can get for losing key free agents — like the Dodgers get for losing Corey Seager — would be eliminated.

That impacted 14 players this year. The union’s proposed changes to arbitration and free agency would impact hundreds of players per year.

“I think players have been monetized and are viewed more as assets than they ever have before,” Clark said.

When Manfred says the union has “refused to budge” on its core proposals since May, those hundreds of players are an intended audience.

Last year, when the union refused to budge on a day’s pay for a day’s play in a pandemic-shortened season, the owners kept repeating that an agreement required the players to play for a discount because no fans would be in attendance. But the agreement did not say what the owners kept insisting that it did, and the players prevailed.

It didn’t take long for MLB owners to impose a lockout once the collective bargaining agreement expired. It may take a long time before the game is played again.

Now, there is no agreement. Keeping the players united could be more difficult. The players know they were routed in the last round of collective bargaining, and Meyer was hired to make sure it did not happen again.

If February comes and goes without a deal, perhaps the players remain united, and Meyer tells the owners the time has come for them to budge. Perhaps the players tell Meyer to budge.

Or maybe not, since revenues are on the upswing. One year after Manfred claimed the teams lost a combined $3 billion in that pandemic season, neither he nor the owners are making any claim of economic distress.

If there were such claims, the league and the teams would be preparing to furlough or lay off employees, as they did last year. No such plans this year, Manfred said Thursday. The baseball games are off for now, and the waiting game is on.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.