- Share via

PITTSBURGH — Before and after football games at Penn State, many in the crowd of 100,000-plus at Beaver Stadium join to sing the university’s alma mater. It’s a tradition meant to promote unity and school pride.

When 2011 graduate Michael Oplinger attended games in recent years, he noticed something different about the inflection people bring to a single line in the song, written more than a century ago.

“There’s a line that says, ‘May no act of ours bring shame, to one heart that loves thy name,’ ” said Oplinger, a high school teacher in Camden, N.J. “People put more emphasis on that line now. It’s deliberate. It’s hard to think of a more shameful act than what Jerry Sandusky did.”

The former Penn State assistant football coach was arrested in Centre County, Pa., on Nov. 5, 2011, on charges of molesting eight boys he had met through his Second Mile charity over a span of more than a decade. Some of the assaults occurred at Penn State’s football building, to which Sandusky still had access after his retirement in 1999.

Jerry Sandusky verdict

The scandal that unfolded 10 years ago this month had a profound effect on countless lives, none more so than those of the boys Sandusky abused. Within a year, Sandusky received what amounted to a life sentence in prison, the NCAA imposed unprecedented sanctions on Penn State, and major college football’s winningest coach had been unceremoniously fired.

Yet it’s difficult to assert that the punishment served as a deterrent. Sexual abuse scandals have continued to surface at major universities around the country — including in Los Angeles.

::

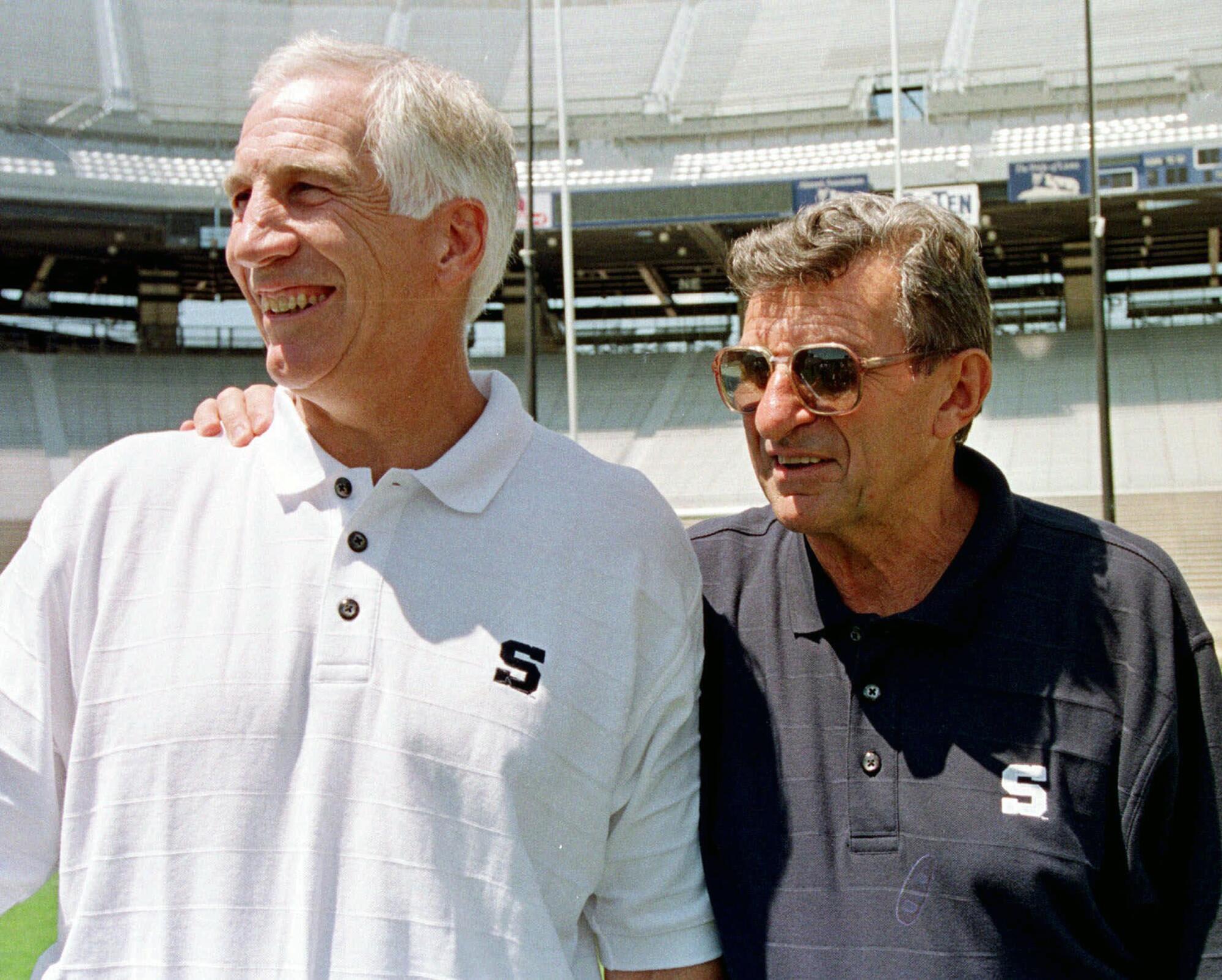

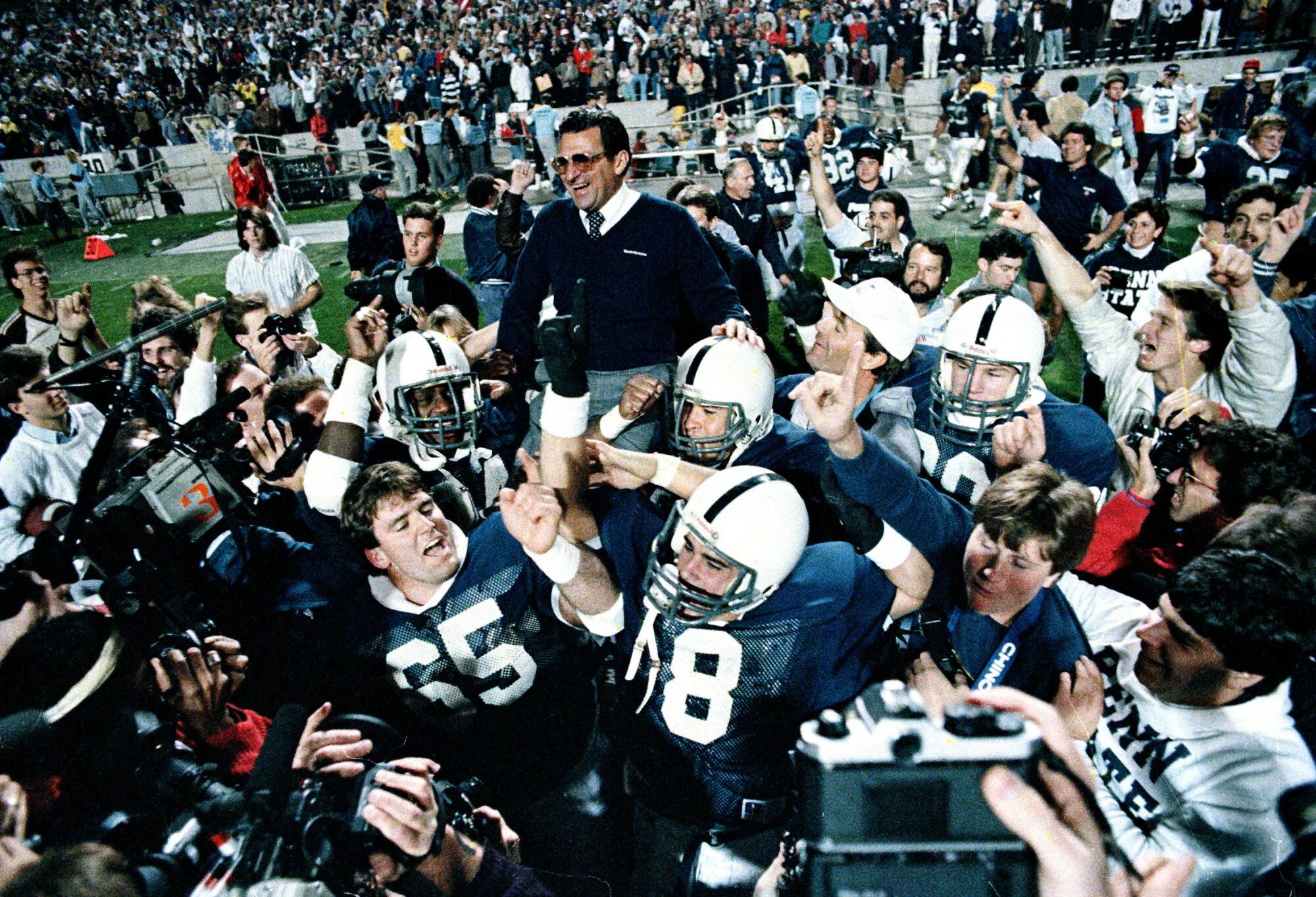

In terms of the immediate fallout from Sandusky’s indictment, no event was more momentous than Penn State’s dismissal of the legendary Joe Paterno, who had worked at the university for 61 years and was head coach for 46 seasons. Although prosecutors made clear that Paterno would not face charges, critics said he should have done more to stop Sandusky, particularly after being alerted to a 2001 assault at the football building.

Four days after Sandusky’s arrest, the Penn State board of trustees fired the 84-year-old Paterno. The coach had announced earlier that day he would retire at the end of the season, but the trustees said they had to act immediately.

When news of Paterno’s dismissal broke, some students took to the streets of State College in anger.

“It was a chaotic, confusing time,” said Lexi Belculfine, who was editor in chief of the Daily Collegian, Penn State’s student-run newspaper. “After the board of trustees meeting, the anger and frustration boiled over.”

Reporters were hit with tear gas, lamp posts were ripped down and a news van was flipped over, Belculfine said.

While some students rioted, others went to Paterno’s house nearby to express their support. The coach came to the door and told the students, “I love you guys.”

::

Two days later, Paterno began coughing up blood, said his son Jay, who had played for Penn State and was the Nittany Lions’ quarterbacks coach. Paterno’s family took him to a hospital the next day.

The media were still staked out in front of Joe Paterno’s house, his son said, so “my sister and my mom had him lie down in the back seat of the car and covered him with blankets and my mom got him to the hospital without anybody noticing he was there.”

“You can’t dismiss 61 years of integrity and honesty and just assume that someone is guilty of something that runs counter to the values they have held for their entire career.”

— Jay Paterno, son of legendary Penn State coach Joe Paterno

Two days later, the family learned Paterno had lung cancer, despite having never smoked and receiving a clean bill of health only four months earlier.

“By late November, most of the reporters had left and my dad and I were able to take walks together and talk in private,” said the younger Paterno, who is now a Penn State trustee. “We talked about what had happened, of course. My dad was not a person who harbored anger; it was more hurt, first, at what had happened to the young people.

“If there was any anger, it was that the overwhelming majority of the incidents hadn’t happened at Penn State and Penn State was really a tangent to the case.”

Paterno defends his father’s handling of the report about a sexual assault Sandusky had committed in 2001. His father reported it to top administrators at Penn State, and according to university policy was not authorized to do more.

“You can’t dismiss 61 years of integrity and honesty and just assume that someone is guilty of something that runs counter to the values they have held for their entire career,” he said.

Paterno rejects allegations that his father had heard whispers that Sandusky was molesting boys and ignored them to protect the high-profile football program.

“I’ve known Jerry Sandusky for pretty much my whole life,” he said. “I knew him as a churchgoing, non-drinking guy who was married and ran a charity that helped a lot of kids.

“My kids were around him. I was around him all the time when I was a kid. Do you honestly think we would have allowed that to happen if we had any idea of what kind of person he really was?”

On Jan. 22, 2012, 74 days after he was fired, Joe Paterno died.

“One of the last notes he wrote before he went to the hospital for the last time, and he never came home, was that hopefully the silver lining is that something good would come out of this,” Jay Paterno said.

::

In June 2012, a jury found Sandusky guilty of 45 counts of child sexual abuse. Still proclaiming his innocence, the 68-year-old former coach was sentenced that October to 30 to 60 years in state prison.

In July, a team led by former FBI Director Louis Freeh released a report commissioned by Penn State’s board of trustees. It concluded that Paterno, fired university President Graham Spanier and two other high-ranking administrators had actively concealed the allegations against Sandusky to protect the football program.

Spanier and the other administrators — former athletic director Tim Curley and vice president Gary Schultz — served time in jail. When they were sentenced in 2017, judge John Boccabella castigated them for not reporting Sandusky to the police. He did not spare Paterno.

Paterno “could have made that phone call without so much as getting his hands dirty,” Boccabella said. “Why he didn’t is beyond me.”

Eleven days after the Freeh report was released, the NCAA announced sanctions. It levied a fine of $60 million against Penn State, banned the team from postseason play for four years and reduced its football scholarships for that span. It also vacated all of Penn State’s football victories from 1998 to 2011, costing Paterno 111 wins, and put the program on probation for five years.

However, the NCAA retreated from the sanctions in 2015 after a judge questioned whether it had the authority to impose them. Paterno’s wins were restored, making him again the all-time leader in major college football. The entire $60 million would be spent in Pennsylvania on programs to treat and prevent child sexual abuse, and the scholarship limits and ban on bowl games were rescinded.

Penn State and the NCAA instituted reforms to fight child abuse, sexual misconduct and unethical actions. Today, university officials stress the progress Penn State has made in improving safety, reporting expectations, background checks, and ethics and compliance. The board of trustees instituted a code of conduct that anyone remotely connected with athletics must follow.

“It’s not talked about as frequently now, but it’s not as though everything is healed now, either.”

— Penn State senior Andrew Destin

“The code of conduct applies to all coaches, managers and student-athletes of NCAA-sanctioned Division I intercollegiate athletics teams; university employees directly involved with intercollegiate athletics teams; the university board of trustees; the president of the university; and all members of the athletic director’s executive committee,” Penn State spokesman Lawrence Lokman said.

Sandusky isn’t a big topic of conversation today for Penn State students, many of whom were in grade school when the scandal developed, said Andrew Destin, a senior who is sports director of the student-run radio station.

“It’s not talked about as frequently now, but it’s not as though everything is healed now, either,” Destin said. “You don’t hear that much about it on campus but more so in the State College community.”

::

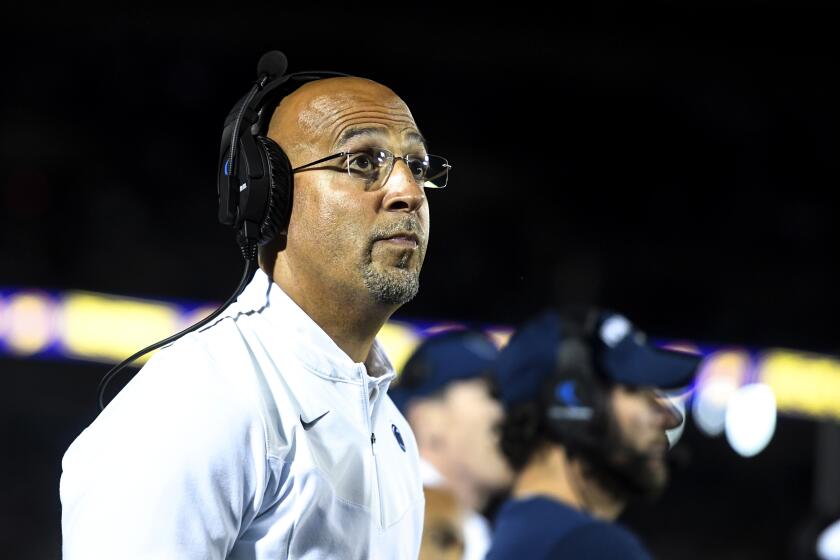

The Penn State football program has rebounded from the Sandusky scandal, although it has yet to be chosen for the College Football Playoff. Coach James Franklin, in his eighth season at Penn State, led the Nittany Lions to the 2016 Big Ten Conference title and had the team ranked as high as No. 4 in this season’s Associated Press poll. The board of trustees voted this year to spend $48 million on renovations to the football building.

Penn State coach James Franklin rockets to the top of any coaching candidate list, but his link to a Vanderbilt rape case may raise questions at USC.

But Penn State’s continued success, leading to packed houses at Beaver Stadium and appearances on national television, might add to the pain of the boys — now men — Sandusky abused, particularly if they still live in central Pennsylvania, where coverage of the Nittany Lions is ubiquitous.

“Healing is a long-term process, and when life is back to normal for everyone else but your life is still in upheaval, it can be really hard,” said Anne Ard, executive director of Centre Safe in State College, which provides counseling and advocacy to victims of sexual and domestic violence.

Those Sandusky preyed on already faced a struggle because of the coach’s celebrity in the region, Ard said.

“This guy was a prominent member of the community, a beloved coach in this famous football program,” she said. “A victim might say, ‘Who’s going to believe me?’ You bet Jerry Sandusky used that to his advantage.”

::

The architect of Penn State’s vaunted defense for more than 20 years, a man who helped the team win two national championships and acquire the nickname “Linebacker U,” today resides in a cell at State Correctional Institution — Laurel Highlands outside Somerset, Pa., about 85 miles southwest of the university campus. He is Inmate KT2386, 77 years old and not eligible for parole for about 21 more years.

The damage Sandusky caused from his crimes is incalculable, starting with an unknown number of boys whose innocence he stole. Penn State, his alma mater and employer for three decades, suffered a terrible blow to its reputation and has paid out over $100 million to more than 30 victims. In addition, the decision to fire Paterno caused deep divisions in the Penn State community.

“It’s still a very polarizing issue, and I know it has driven rifts in relationships,” said Belculfine, the former Daily Collegian editor.

However, something positive might have come from the shameful episode.

“It changed how we see the world and how we view authority and how we take care of each other,” Belculfine said of herself and her classmates. “When I think about that time, what stands out is the importance of putting people who need help first.”

Sandusky’s crimes, along with the scandals at other universities since then, have made more people attuned to the issue of sexual abuse of young people. That is certainly the case in Centre County, Ard said.

“Could we say categorically that something like [the Sandusky scandal] isn’t happening right now at another university? I don’t think we can say that.”

— University of San Francisco vice president of operations Donald Heller

“I believe that we’re a much wiser community now,” she said. “We’ve probably trained 10,000 people on looking for the signs of and preventing child sex abuse, and that training continues. But we have to realize that there are still sexual predators out there and we have to be vigilant.”

::

Donald Heller, vice president of operations and a professor of education at the University of San Francisco, taught at Penn State in 2011 and has consulted on higher education policy issues with university systems around the country.

Like virtually everyone else at Penn State, Heller was stunned by the allegations against Sandusky — and the university’s lack of an immediate response.

“It was a systematic failure in the university,” he said. “As someone who had worked with the leadership of the university on a number of issues, it was disappointing. We wanted to see the leadership step up and comment in support of the victims and they did not.”

At the end of the fall 2011 semester, Heller left Penn State, making an already-planned move to Michigan State to become the dean of the College of Education there. Four years later, he departed Michigan State for a post at USF.

In 2016, an investigation by the Indianapolis Star led to a physician from Michigan State who had long worked for USA gymnastics, Larry Nassar, being implicated in sexual assaults of girls and young women going back decades. Some of Nassar’s victims said that they had reported his abuse to Michigan State officials and trainers over the years and the university had not investigated.

“My reaction [to the Nassar scandal] was one of horror, because of the allegations and the sheer number of women who were victimized,” Heller said.

Since then, sexual abuse scandals have emerged at other major universities, including in the athletic departments at Ohio State and San Jose State. Earlier this year, USC agreed to pay more than $1 billion to former patients who accused campus gynecologist George Tyndall of sexual abuse. At UCLA, sexual abuse allegations against gynecologist James Heaps led to a $73 million settlement that will be divided among thousands of women.

“Could we say categorically that something like [the Sandusky scandal] isn’t happening right now at another university?” Heller said. “I don’t think we can say that.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.