NBA legends like Dr. J agree: Elgin Baylor revolutionized game

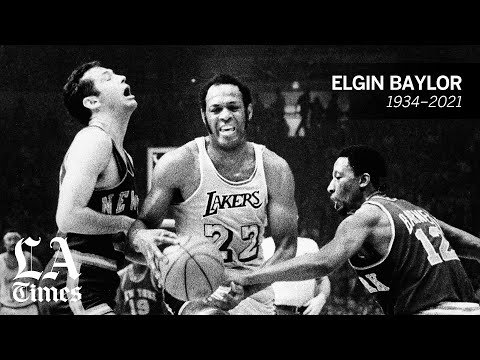

Elgin Baylor, the Los Angeles Lakers’ first superstar and one of the greatest players in NBA history, died Monday, the Lakers announced. He was 86.

- Share via

Elgin Baylor died Monday, but he’s not gone. Never will be. In every dunk, every spin, every funky side-step, pieces of the Lakers legend live on.

The modern NBA is indebted as much to Baylor as it is to any player, one man who introduced eye-opening creativity and athleticism to a game obsessed with fundamentals. There’s a good chance the players who are worshipped now either worshipped Baylor or worshipped someone who worshipped Baylor.

When it comes to greatness in the NBA, almost all roads point Baylor’s direction, the lack of a championship ring unable to cloud the undeniable impact he had on generations of the game’s legends. If you didn’t get a chance to see it you missed something easily defined.

“It was the greatest show on Earth,” Julius Erving said by phone on Monday after he learned of Baylor’s death at 86. “Literally, you could watch him play a basketball game and you’d want to go right outside and do what you saw.”

In the evolution of basketball, in its ascendance from activity to professional sport to entertainment, Baylor set the tone — a legion of NBA stars and Hall of Famers citing him as the beginning of an era where the action above the rim would be even more spectacular than the play below it.

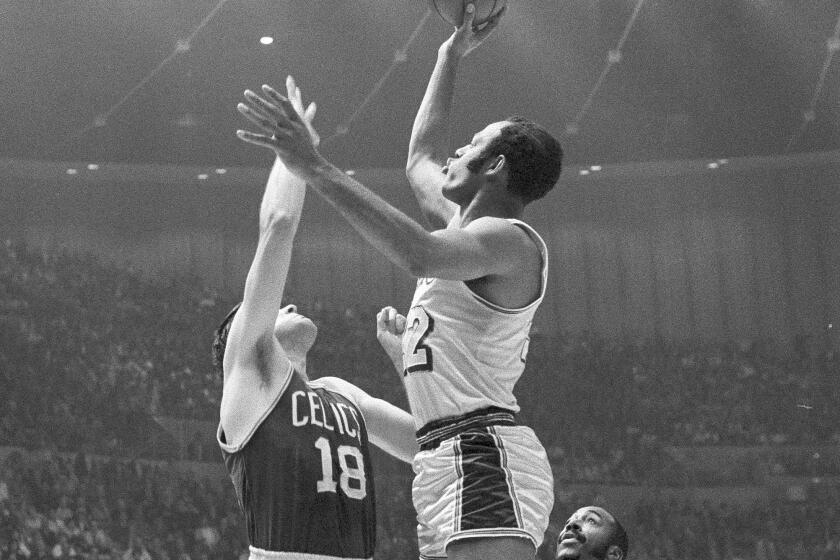

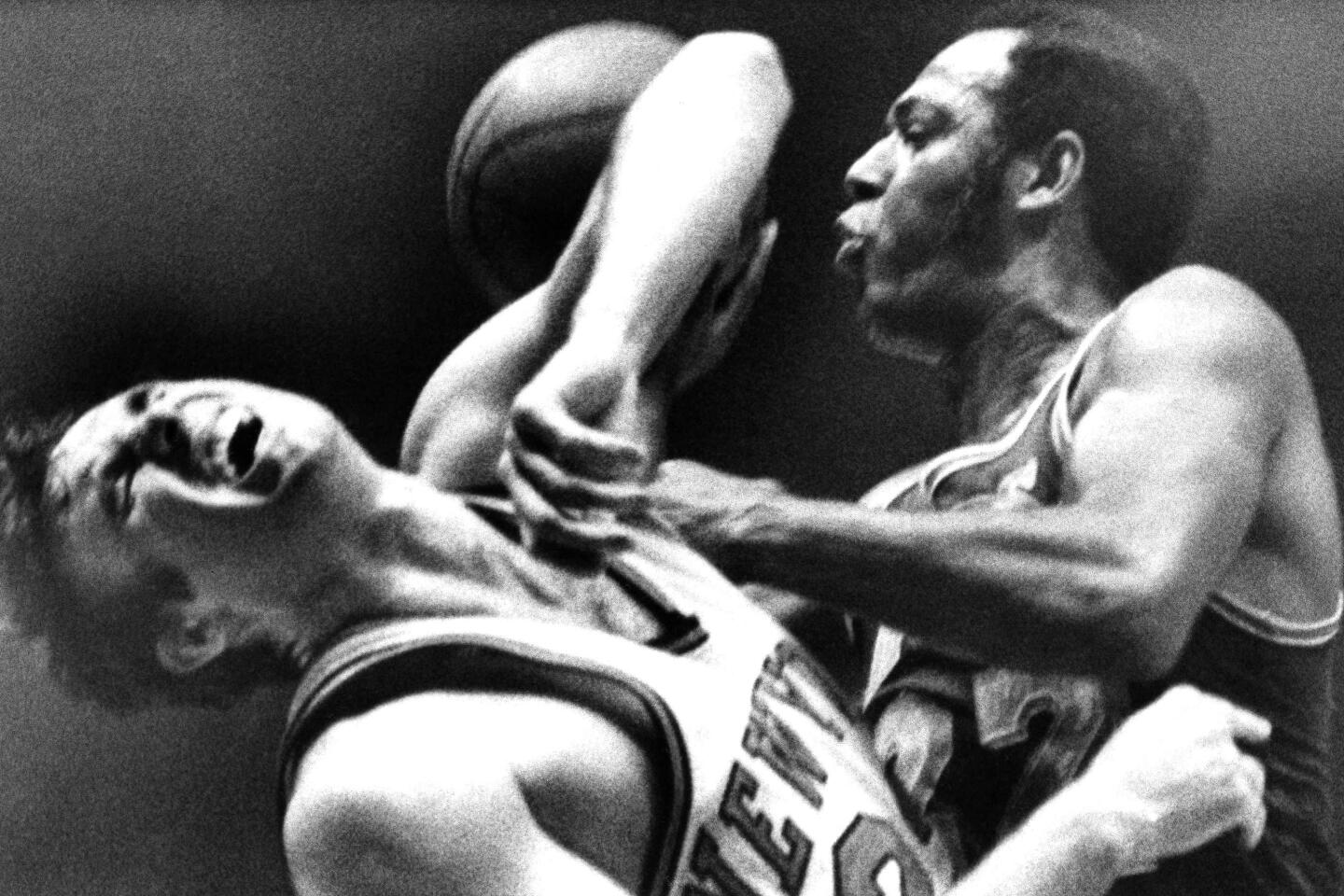

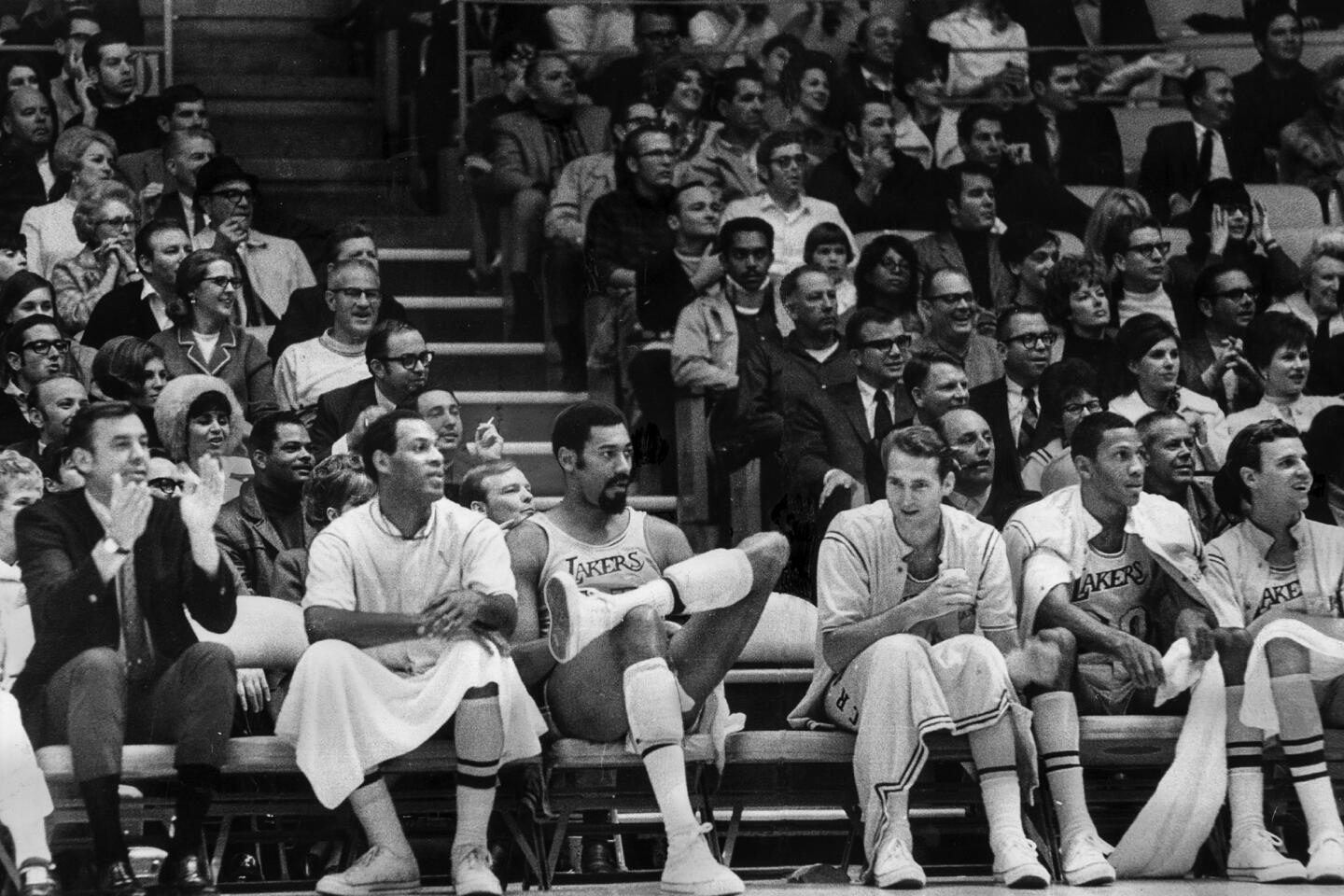

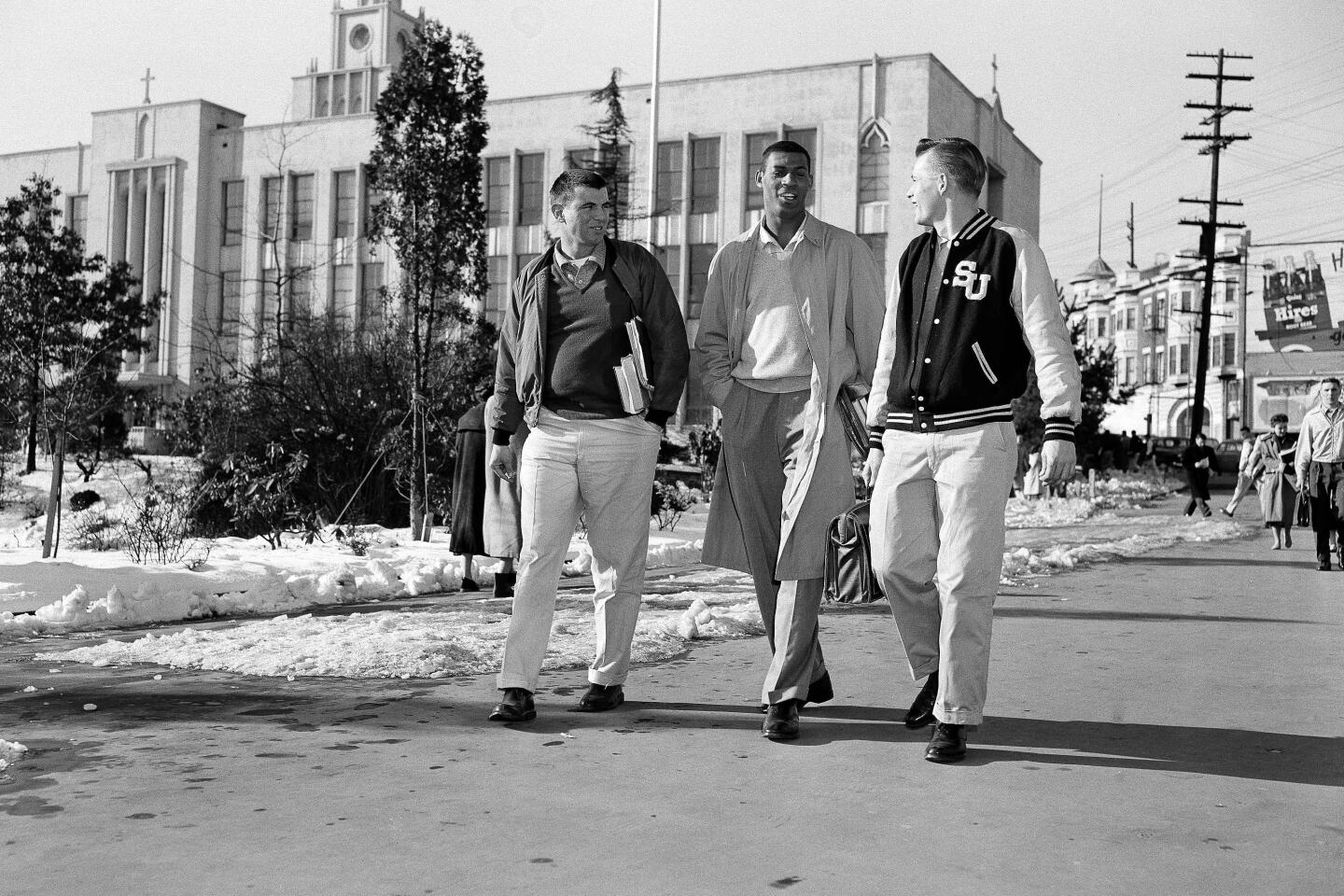

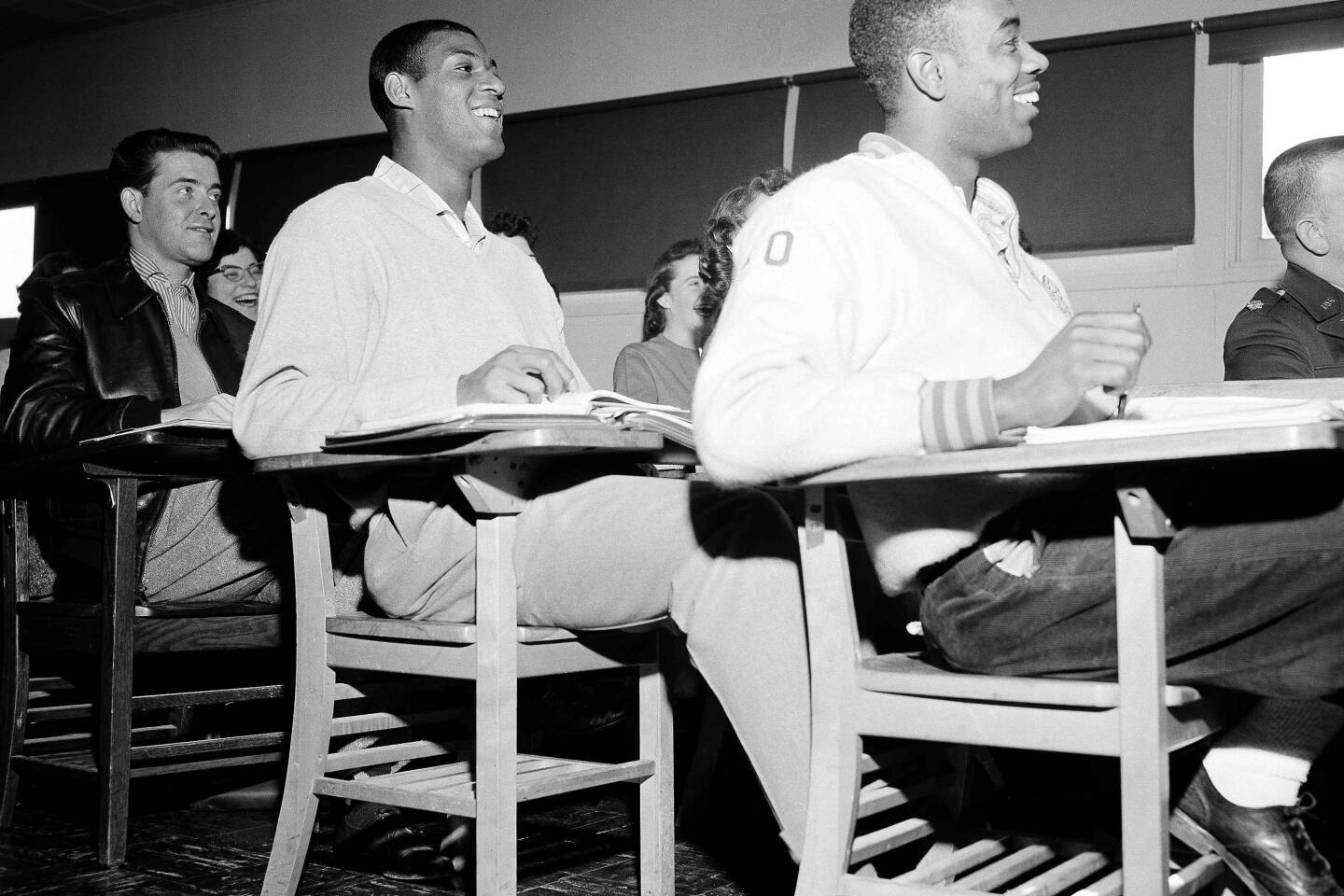

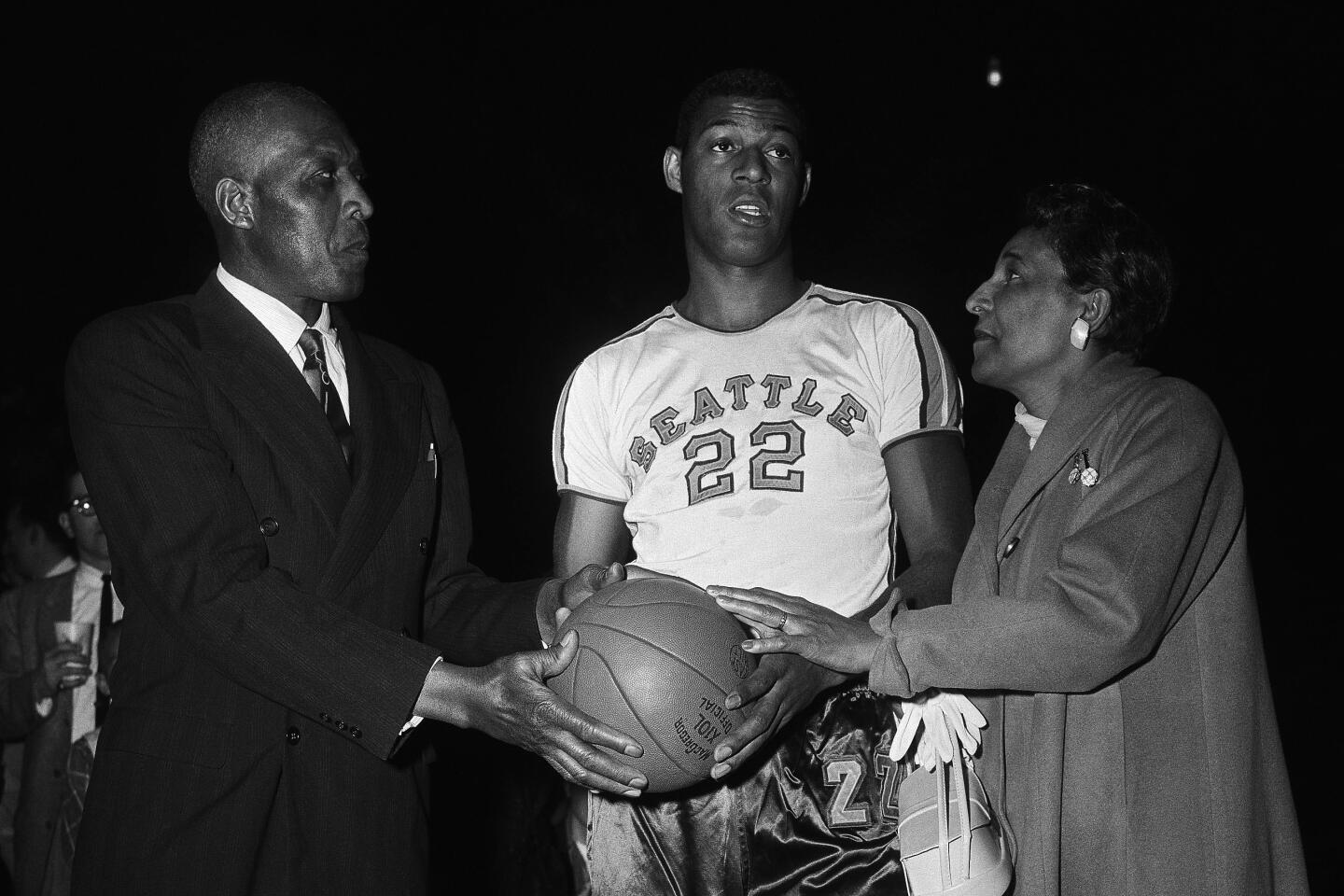

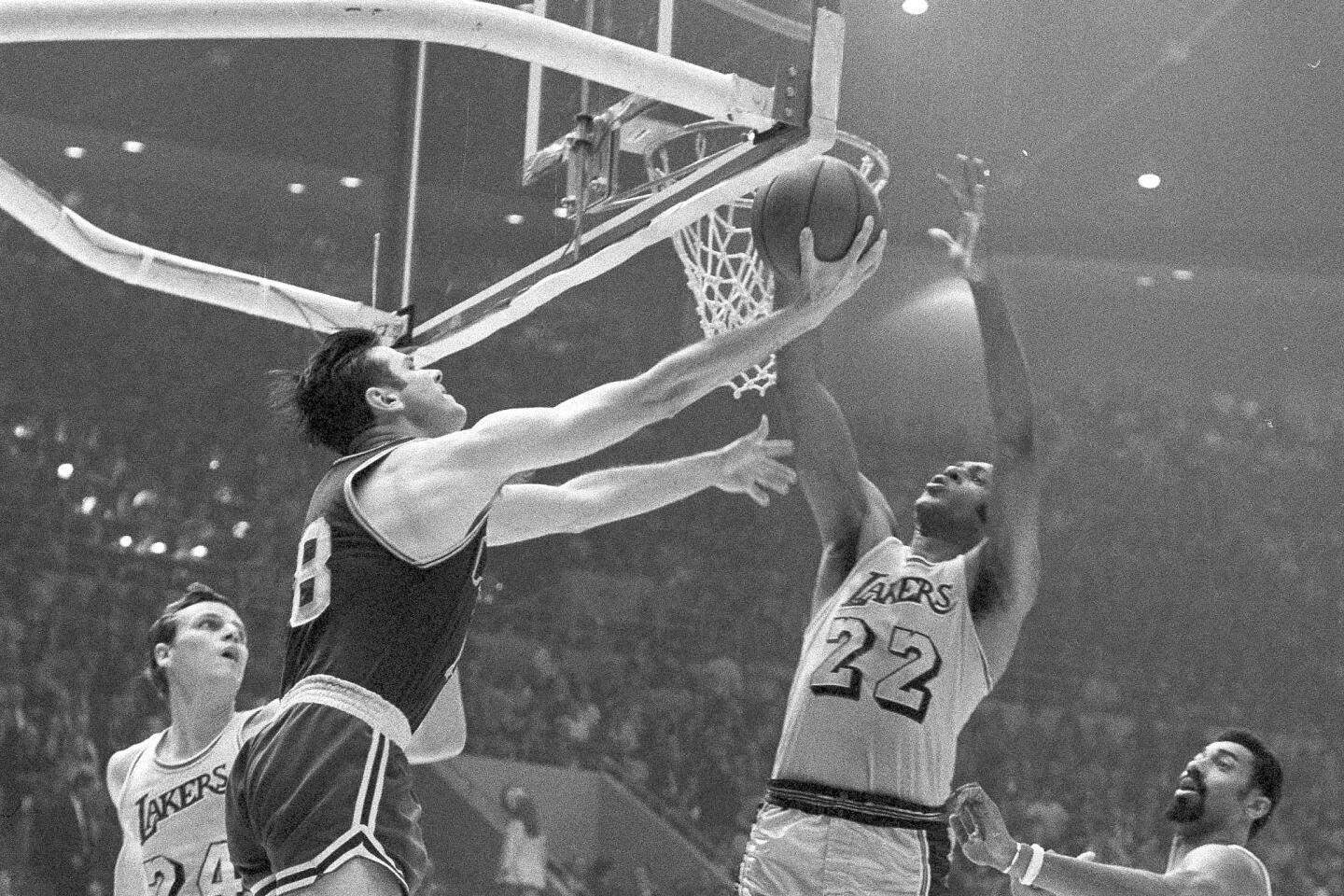

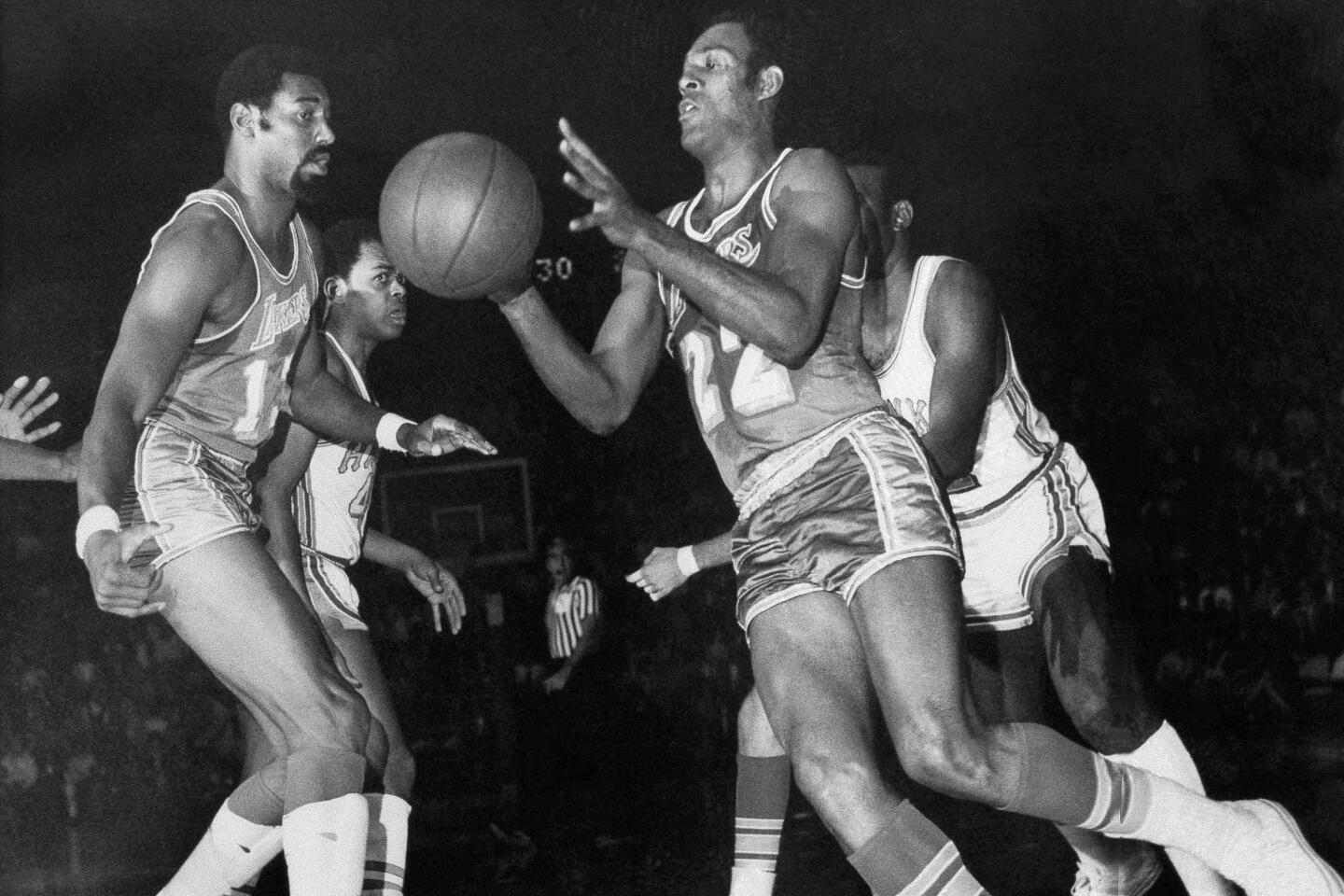

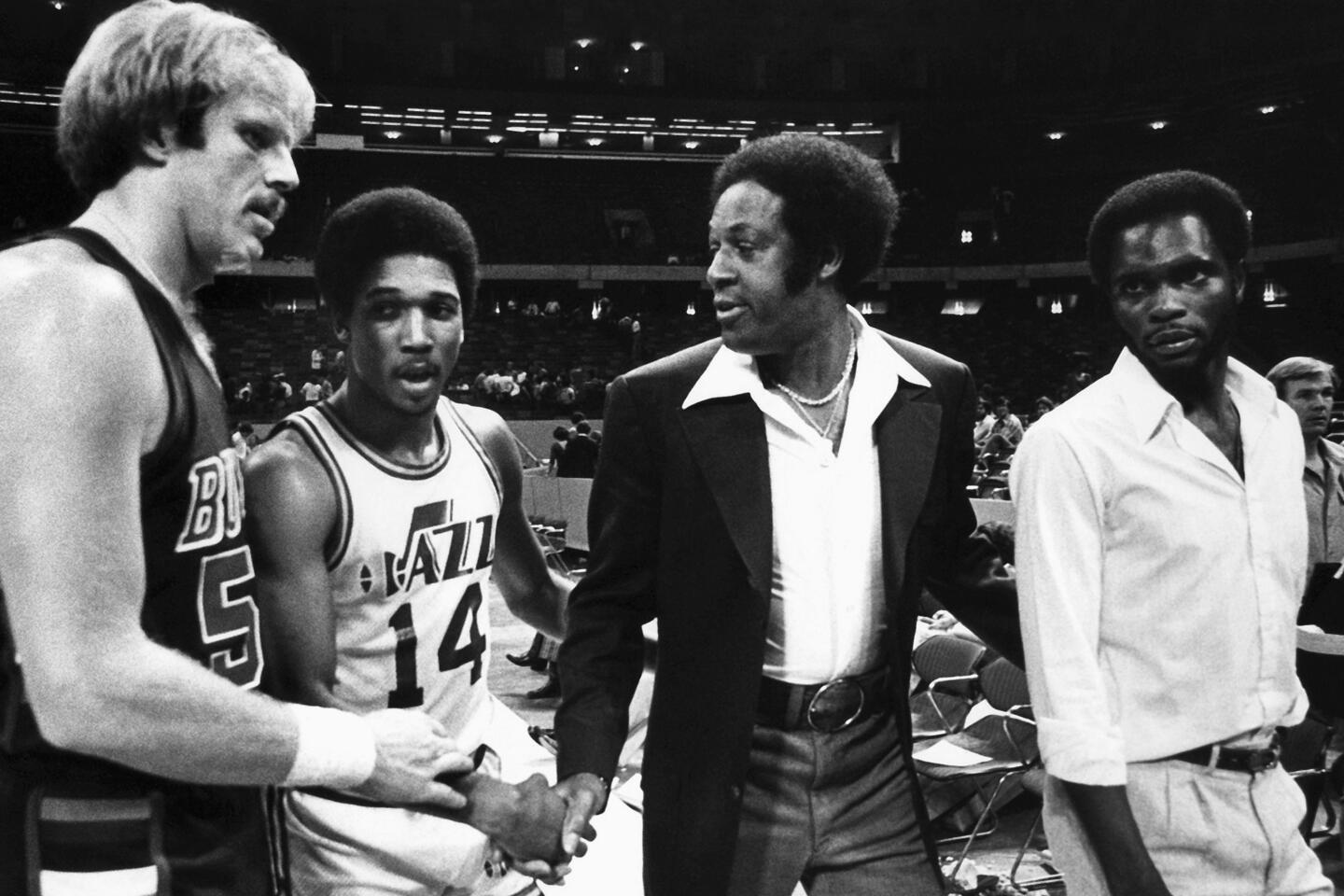

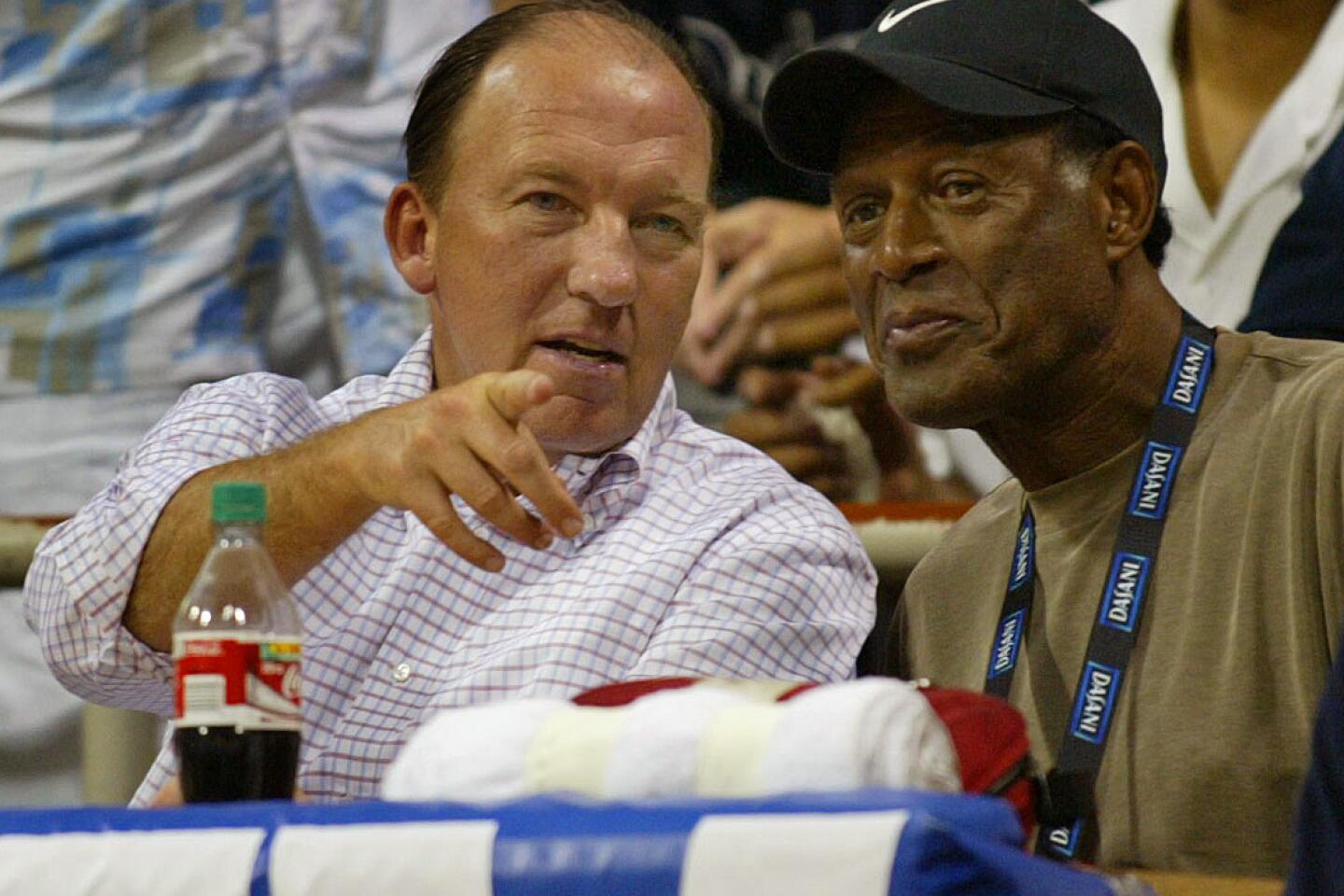

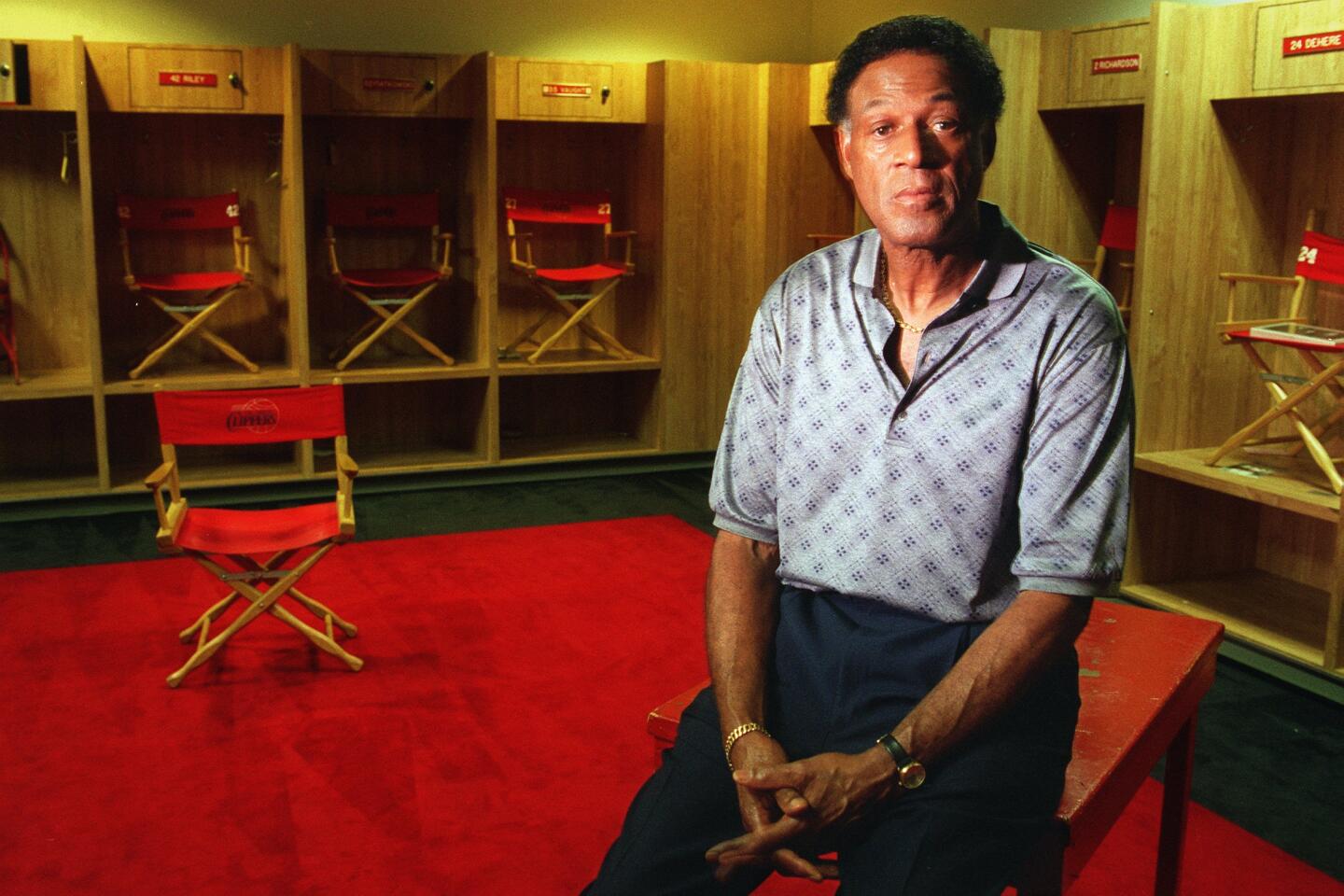

A look at the life and playing days of Lakers Hall of Famer Elgin Baylor, who would become an executive with the Clippers.

“If I had not seen him play, the ideas in my mind and even things I would dream about doing, I probably wouldn’t have dreamt about those things if I hadn’t seen him do it,” Erving said. “It would’ve made a huge difference in my approach to the game.”

Michael Jordan’s childhood idol, David Thompson, is another Baylor disciple, someone who had their eyes opened to what basketball could be by the Lakers’ legend.

“I used to pretend to be Elgin Baylor, in the backyard, shooting baskets, even down to the way he shot free throws, where he’d look over at his left bicep before he took the shot,” Thompson said. “He had fantastic one-on-one moves, great footwork and would just swoop to the basket. if you didn’t watch, he’d take it to the basket and flush on you. I really liked that part of the game, playing above the rim. Seeing him go and dunk on the big guys. It was very exciting.”

“When he went to the basket, I don’t care who was back there, you were going to have a difficult time stopping him,”

— Lenny Wilkens, NBA great

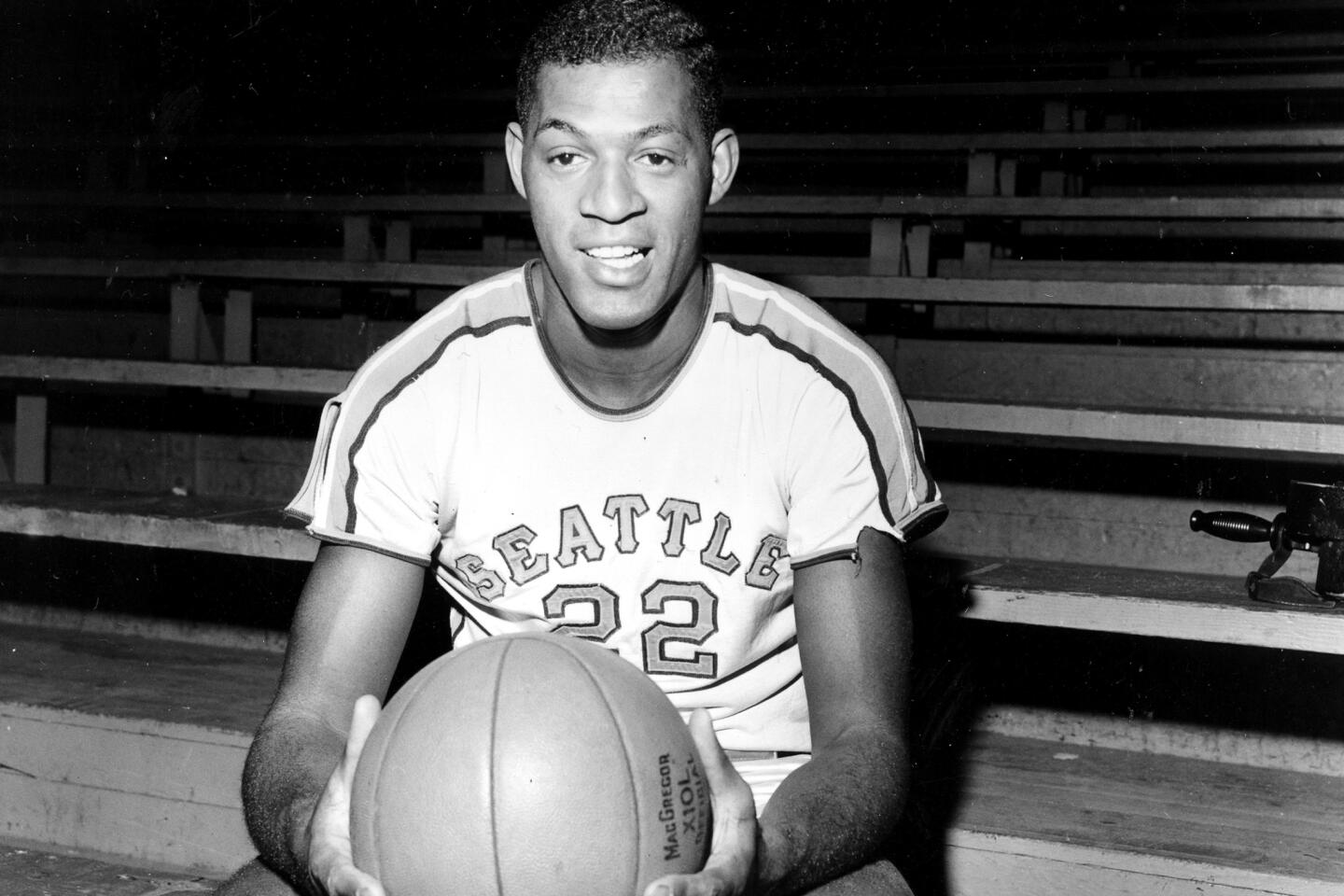

Former Detroit Pistons guard Dave Bing grew up in the same Washington neighborhoods as Baylor, scooping up the No. 22 jersey on his high school and college teams as a tribute. Before he became a pro, Bing and his friends would crowd the city’s courts to watch Baylor and Wilt Chamberlain play against one another in playground battles that are still legendary on the East Coast.

“He was everybody’s idol in D.C. That’s for sure. Everybody wanted to be like Elgin,” Bing said Monday. “It was outside on a hard-court playground that had lights. It was lot of us from the neighborhood — and it was advertised, so a lot of people from the whole city. Wilt and Elgin Baylor were two of the biggest names in basketball, playing on an outdoor court in D.C. at night. It was just a sight to behold. …

“We all gravitated. Wherever he was going to go play, if we had a chance to go see him and we obviously did that.”

Once Bing finally made it to the NBA, he sent word to Lakers rookie Jerry Chambers, who was also from the same D.C. neighborhood, that he wanted to get into the Lakers locker room to talk with Baylor.

“I got in contact with Chambers and said, ‘I want to come into the locker room and just say ‘Hey’ to Elgin. And he got me in and we had a nice conversation,” Bing remembered. “We’re from the same neighborhood, same high school. He was just such a great player. ...

“I knew I couldn’t play like Elgin and couldn’t do the things he did — but I tried.”

Many legends said they did the same — Thompson, Erving and Marques Johnson, then just a kid from South L.A. with bad seats for Lakers games at the Sports Arena.

“He was the guy where I would go right to the playground. I’d try the crazy reverse layups, the spin, and all that stuff,” Johnson said. “It’s commonplace today, but back then, nobody was doing it. He was doing stuff, no-look spins, penetrate, look one-way, and spin it without looking, high spins off the glass right through the net. It was a lot of the stuff that I tried to incorporate into my game was based on his body control.”

Even for the players trying to stop him, it was impressive.

“When he went to the basket, I don’t care who was back there, you were going to have a difficult time stopping him,” Lenny Wilkens said Monday with a laugh as he acknowledged, that yeah, he could get caught up watching Baylor when they were competing.

“One thing I loved about his game was that he could hang in the air, which was so beautiful. You’d see him go up and just wait for everyone to come down.”

— David Thompson, former NBA All-Star

Wayne Embry, a 6-foot-8 mountain of a center before becoming one of the NBA’s most respected executives, said Baylor was so strong that he could simply move you whenever he wanted.

“There were times I’d get switched out onto him and I hated it,” he said with a deep laugh. “Yeah. Hated it.”

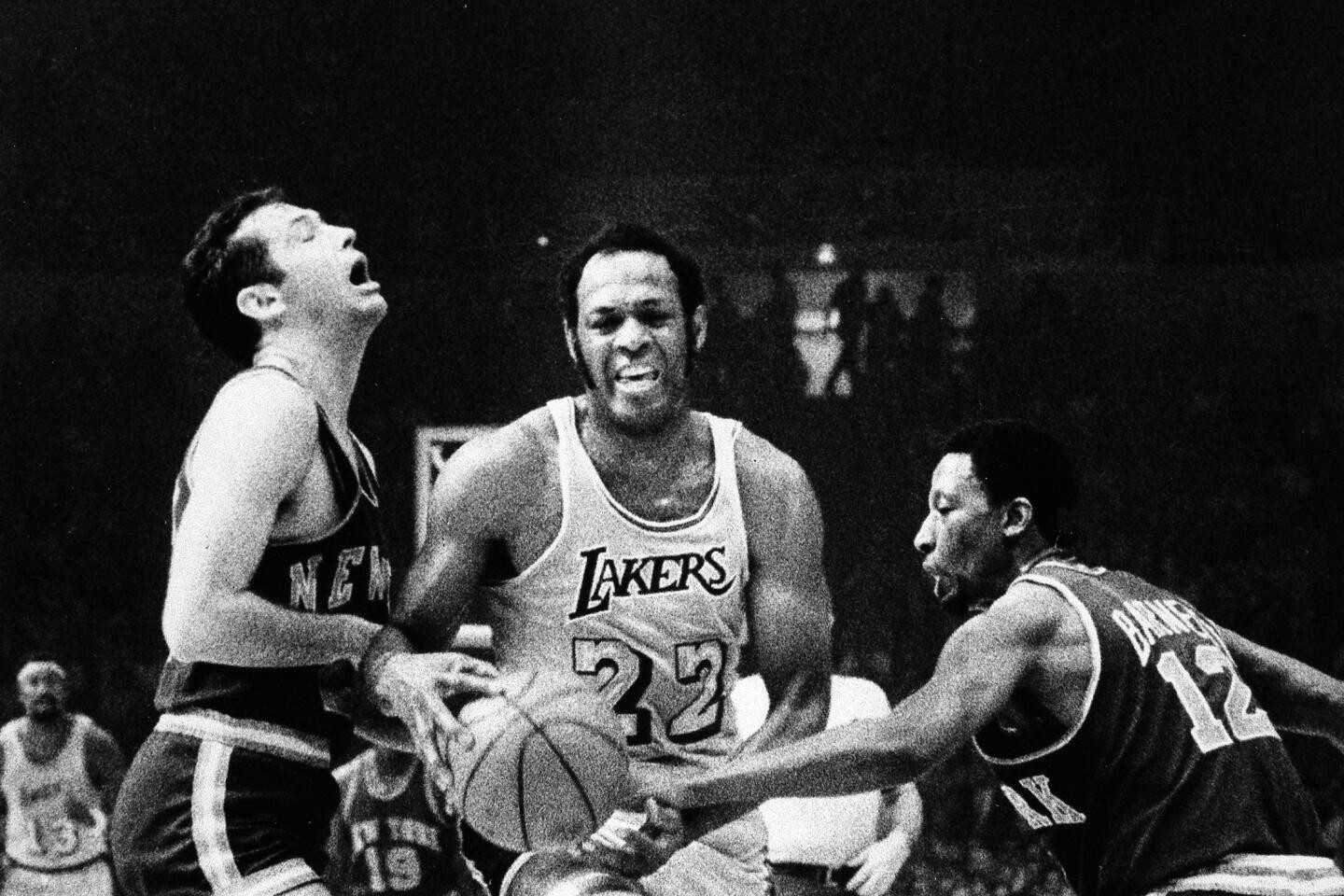

The numbers were absurd — 27.4 points, 13.5 rebounds and 4.3 assists per game all while being undersized as a 6-foot-5 forward. He had 71 points and 25 rebounds against the New York Knicks in 1960. He scored a still-record 61 points against the Boston Celtics in the 1962 NBA Finals.

“He’s right there with the best players ever,” said Embry, now a senior basketball advisor with the Toronto Raptors. “So many times when I talk to our players … they think the game was invented with Michael [Jordan]. And not to take away from Michael’s greatness, because he certainly was, but Elgin Baylor wasn’t a good player. He was a great player.”

The reverence the best to play the game have for Baylor speaks so loudly as to how good he actually was, the grainy footage on YouTube confirming the stories.

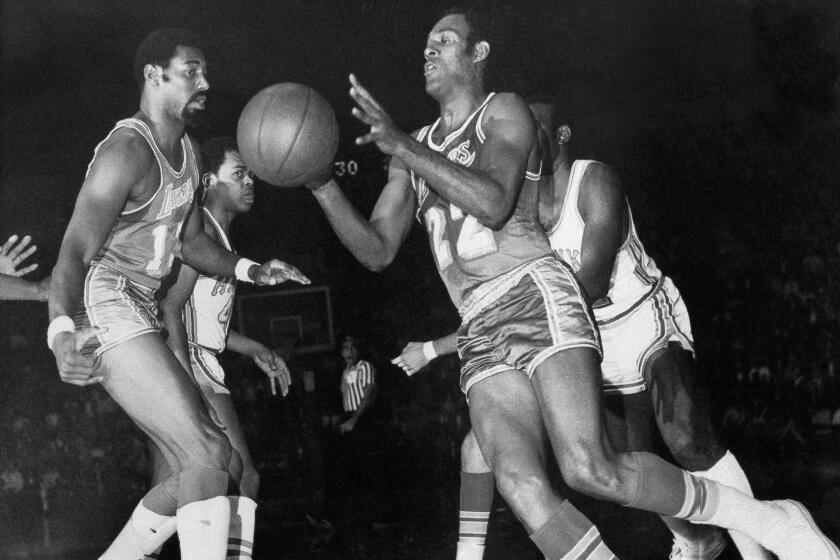

Press play and there’s Baylor side-stepping a defender — they call it a Euro step now. There he is floating from one side of the basket to the other, suspended in air while everyone else succumbs to gravity. Jumpers from deep. Baskets at the rim.

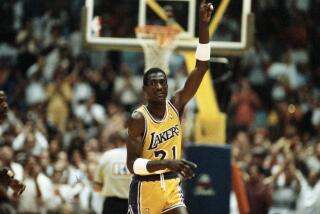

Highlights from Elgin Baylor’s NBA career.

“He was very fluid. That footwork …” Thompson said. “One thing I loved about his game was that he could hang in the air, which was so beautiful. You’d see him go up and just wait for everyone to come down. And then it seemed like he would jump again and put the ball in the basket. He was acrobatic out on the floor.”

They were all eager to share their respect for someone they credit with starting the game’s evolution.

“He was absolutely at the forefront,” Erving said. “He’s the guy, who if he was in his prime in today’s game, he’d be a dominant player. The way the guys play now, Elgin would score like 50 points a game. The defense would just wave at him.”

Elgin Baylor never received the level of adulation from Lakers fans that other team legends received. He was a pioneer in a town with a short memory, Bill Plaschke writes.

When Bing, who was the mayor of Detroit, returns to Washington to visit family and friends, they still talk about Baylor, about how he’d tell someone brave enough to challenge him what would be coming once the game would start.

“He was not a guy who did a lot of trash talking. But he would let guys know if they felt they were going to come up against him and show him up or something, he let them know that it wasn’t going to happen,” Bing said. “He’d light people up — and then afterwards go to the sidelines and have a good time with people on the sidelines.

“His game, it was so ahead of the game. People look at whether it’s Michael or LeBron … back then, Elgin was what they were. … He had no weaknesses, nothing that he couldn’t do.”

When news of Baylor’s death began to circulate on Monday, Johnson went to social media to share stories and connect with friends from his Crenshaw High days, with grown men sending crying emojis to one another over the loss of their idol.

“He was our guy,” Johnson said.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.