- Share via

Damian Avalos has a dream. It goes like this: Start his first game as the Roosevelt Rough Riders’ quarterback. Lead them to a win over archrival Garfield in the “East L.A. Classic,” their first in a decade. Make a run in the playoffs, shocking the whole Southern California prep football scene.

He can almost touch it. And yet, halfway through his senior year, the vision feels more abstract with each passing day. Earlier this month, he and his teammates were told that they could no longer work out together in preparation for a spring season because of rising numbers of COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations — a major blow to the psyche. Now Avalos is having trouble getting himself to sleep at night.

“When I’m laying down in bed, I just start thinking those thoughts, and it makes me frustrated,” he said. “Because me, as one person, I can’t control the whole state. But if I was a leader, I would control everyone and just make everyone be safe.”

Across the country in Texas, Dewayne Coleman had a dream, too, entering his senior year. The vision went like this: Take his San Antonio Roosevelt Rough Riders to the playoffs. Beat powerful neighbor Converse Judson. Earn a college scholarship.

Even in Texas, where “Friday Night Lights” is not a pop culture reference but a way of life, Coleman worried that COVID would shut down football just like it did his track and field season last spring. But Texas decided to let its young men play, trusting that the boys’ passion for the sport would guide them in following a long list of health and safety protocols.

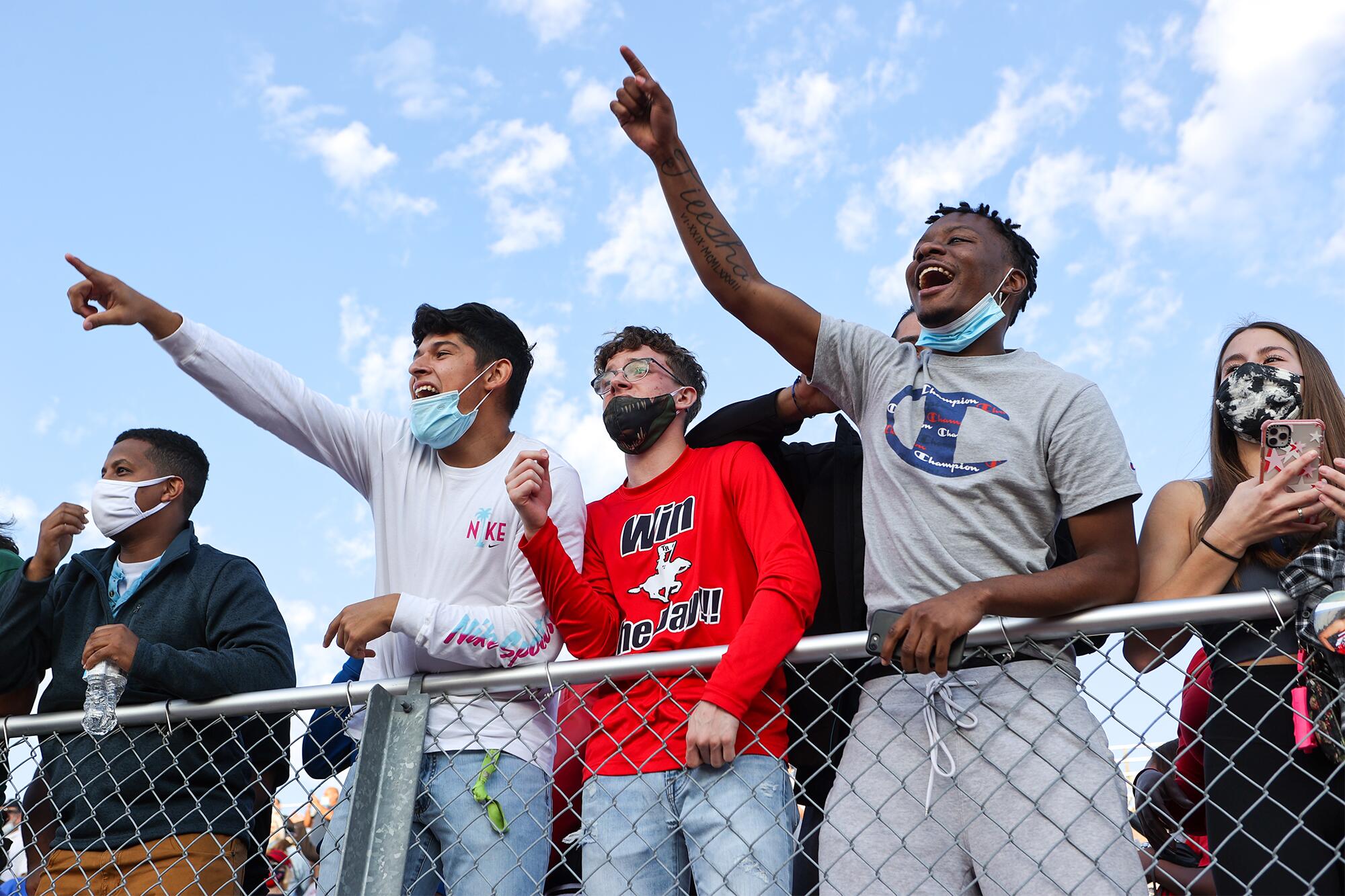

Months later on a December Saturday afternoon, there was Coleman barreling over a Judson linebacker for the game-winning touchdown in the final minutes of a first-round playoff game. The Rough Riders won, 28-21, a result the San Antonio Express-News called a “stunner,” and thousands of fans in the stands went wild.

“Coach gave me a QB power, and I was just determined to score for my team, my school and the whole Roosevelt community,” Coleman said.

And what of L.A. Roosevelt? Nothing about weighing what’s best for teenagers against what’s best for public health is simple.

The decisions of state high school athletic associations on fall football reflected the nation’s coronavirus response. They were highly varied and often driven by each region’s political leanings.

America’s 14 Roosevelt Rough Rider football teams tell the tale, with L.A., Fresno, Portland, Ore., Seattle, Honolulu, Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Long Island, N.Y., opting not to play while San Antonio, Sioux Falls, S.D., Johnstown, Colo., and Kent, Ohio, staged their seasons. St. Louis and Des Moines started seasons only to play one and two games, respectively.

Avalos understood why California postponed football, but at the time he assumed there would be games in the spring. He respects the seriousness of the coronavirus after contracting it during the summer as it spread through the two-bedroom home in Boyle Heights he shares with his mother, grandparents, sister and uncle. Avalos lost his sense of taste and smell and battled headaches, but nobody in his family died. He knows they are lucky.

Avalos is not advocating for high school football over health and safety. He has seen the real-life effects of the pandemic, how so many lives have been toppled by economic hardship, like his grandfather who lost his job.

“I would want the officials to make a way for all people to play the sport they love.”

— Dewayne Coleman, San Antonio Roosevelt High football player

But he has also seen prep football games played in parts of the country that have been hit hard by the virus. It doesn’t feel fair — an opinion shared by that other Rough Rider quarterback in the Lone Star State.

“I would want the officials to make a way for all people to play the sport they love,” Coleman said. “Because it’s more than just a game. It’s a brotherhood. It’s a family. It builds your character. Football has made me who I am today. There can still be things done to give that back to someone.”

::

In the summer, the L.A. Roosevelt kids remained hopeful. Case numbers had risen during the pandemic’s second wave, but relative to other parts of the country, Southern California was doing OK it seemed. The cool thing for Roosevelt coach Aldo Parral was that he didn’t have to keep his players updated.

“They were paying attention to the numbers,” Parral said. “Every kid knew who the L.A. county health director was. And it’s funny because we coaches became teachers of health.”

On July 20, the word came down from the California Interscholastic Federation that fall sports would be postponed to the spring semester, with its football championships scheduled for April.

In August, when Roosevelt players saw high school football games aired on national TV, they had questions. Lots of them.

“Why are they playing and we’re not?” one player asked in a Zoom meeting.

Parral was now functioning as a civics teacher, trading in his whistle for a government textbook. Fortunately he’d spent some years in Roosevelt’s social studies department.

“Look,” Parral recalls saying, “We live in a Democratic state. They live in a Republican state.”

Parral may have oversimplified it a bit, as some blue states did choose to play in the fall.

The players also asked him why schools in the CIF Southern Section, many of them in Orange County, were allowed to at least work out together while they weren’t. Parral told them that there are more Republicans in those areas than in the city and that suburban locales are less densely populated.

“And the other thing I had to explain to them, L.A. Unified does not have deep pockets, and liability is huge,” Parral said.

Sports in 2020 was an emotional rollercoaster of the strange, sad, inspiring and jubilant. Times Sports looks at the year’s biggest moments and storylines.

So Roosevelt stayed in Zoom mode, the boys staring into their screens all day, for school and football.

“As a teacher, I’m totally grateful that our union is fighting to make sure that we are protected and safe,” Parral said. “As a football coach, I hate it, because I want to be out there with the guys.”

The states who approved a fall season each had their method of trying to fit in a season with virus-related disruptions.

Football-obsessed Ohio, for instance, shortened the regular season and had the playoffs start in October instead of November to make sure it could complete its championships. That backfired on Kent’s Rough Riders when their first game was canceled because of an opponent COVID issue and their next two games were wiped out by a Roosevelt player testing positive.

“For our kids who have been treated unfairly because of the color of their skin or where they live, it just seemed like, man, there’s another unfortunate situation for us.”

— Mitch Moore, football coach at Roosevelt in Des Moines, Iowa

On the morning of what was supposed to be their second game, senior center John Schwaben texted a teammate about giving him a ride to the stadium.

“Dude, the game is canceled. Someone has COVID,” his friend responded.

That meant 14 days of quarantine for the whole team due to contact tracing. Kent Roosevelt had played just two games, both losses, when the playoffs began.

“2020’s been a weird year,” said Kent Roosevelt coach Alan Vanderink.

In Iowa, the state ruled that if a school did not offer in-person learning then it could not compete in sports. The Roosevelt Roughriders knew there was a possibility the Des Moines Public Schools would choose to go all virtual, but they scheduled two games in August before the fall semester began and tried to stay optimistic.

The Roughriders lost to suburban West Des Moines power Valley in their first game but showed promise, then roughed up fellow city school East 60-10. The next week, they were informed that DMPS was offering no in-person classes and their football season was over until further notice.

Roosevelt coach Mitch Moore was incensed that the five inner-city Des Moines schools were the only teams in the state that could not play. Moore says that many schools in Iowa offered in-person classes but had their football players attend online to keep them COVID-free. Somehow, that was allowed.

“We’re actually the safest school in the state, and they didn’t let us play?” Moore said. “For our kids who have been treated unfairly because of the color of their skin or where they live, it just seemed like, man, there’s another unfortunate situation for us.”

The Roughriders responded by organizing a protest with the other city schools. In September, they marched together to the governor’s office, carrying signs. The Roosevelt players wore their Black Lives Matter sweatshirts that Moore had gotten for them over the summer. The cheerleaders came along, too, for extra spirit.

She’s one girl with family in two places. Playing five sports helped her cope — until the quarantine

Dalia Hurtado is a tough girl with a tender heart who participates in five sports. She stays active to keep her mind off the daily struggles of life.

“Everybody in the city felt the pain of our kids not getting an opportunity to compete and play,” Moore said.

After case numbers improved through the fall, DMPS opened for in-person learning in mid-November. Moore seized the moment and scheduled a game for Nov. 17 against North, hoping to give the seniors one last shot to play.

Senior cornerback Jakari Bradley had taken advantage of the team’s two prior games to earn a scholarship offer from Division II Upper Iowa. Moore told him that Iowa State of the Big 12 Conference had shown interest but wanted to watch him play again.

The week before the North game, DMPS said it was going back to virtual learning. The game was canceled.

“Could have changed my whole life,” Bradley said.

===

In Johnstown, Colo., Roosevelt quarterback Brig Hartson’s senior dream went like this: Beat the rival Mead Mavericks. Win the school’s first state championship. Celebrate with his football-crazy town nestled in the cornfields an hour’s drive north of Denver.

At first, Colorado’s state association planned to push the season back to the spring. But Roosevelt coach Lane Wasinger didn’t just accept that edict. He was one of many coaches who applied pressure on social media. While he hoped the state would reverse course, he asked his players to treat the fall as they would spring football normally and use the time to get bigger, faster, stronger.

So that’s what Hartson did — until one September morning. Once the team had arrived for weight training, Wasinger told them that they were going to have a fall season after all. He had a schedule printed up and everything.

“We all went into the parking lot and were jumping around,” Hartson said. “To see a schedule on paper, it was kind of hard to believe for a second.”

In South Dakota, despite the state’s status as a COVID hotbed, there wasn’t much doubt about whether there would be a fall season. That was great for the Sioux Falls Roosevelt Rough Riders, who were ranked No. 1 in the preseason.

They still had strict protocols to follow, which led to some uncomfortable conversations.

“Some of that just comes from what their belief system is at home, how they felt their rights were being controlled a little bit,” said Roosevelt coach Kim Nelson, the state’s all-time wins leader. “We had some guys that maybe didn’t always follow the guidelines, but I would say close to 90% were pretty good.

“It was hard because we really had to talk a lot about our civil rights and individual rights, and the people that lost family members were very adamant about wearing masks and trying to get everyone else to do the same.”

“These last few months have been some of the most memorable of my life. I feel a lot of remorse for those teams that don’t get to experience this.”

— Brig Hartson, quarterback at Roosevelt High in Johnstown, Colo.

Sioux Falls Roosevelt has 2,600 kids, a thousand of whom chose virtual learning. The school requested that students who attended in person wear a mask, but there was so much blowback from parents that Roosevelt made a list of kids who did not have to wear a mask. The mask-free students in each classroom were isolated into a different area from the kids who wore masks.

The Rough Riders took a 7-0 record into the state semifinals. It was then that Nelson received the news that the mothers of two of his offensive linemen tested positive and another lineman tested positive after interacting with a student who did not wear a mask in class.

Without three big guys up front, Roosevelt lost in the semis. Nelson did not blame his team’s COVID situation, but it certainly did not help.

A look at the high school sport standouts whose seasons were cut short by the coronavirus outbreak.

Overall, Nelson views the season as a success.

“I didn’t hear of anyone who traced any close contact or positive test to a football game, or being in the bleachers next to somebody,” Nelson said. “I think being outside was a big factor for us to stay healthy.”

In Kent, Ohio, the Rough Riders fell in the second round of the playoffs. Thanks to those early cancellations, their record was just 1-3. But they were able to schedule three more games to finish out the year, allowing the boys to play for pride. They rallied to finish 4-3 with a victory over rival Ravenna in the finale, clinching their first winning season since 2013.

“There was a lot of emotions because it was our last game for our seniors,” Schwaben said. “We were sad that high school football was ending for us, but we were able to get that last one win as a team and beat the school that we hate the most. There’s definitely more highs than lows.”

That’s how Brig Hartson would come to see it, too, as his dream unfolded in front of him and became reality. Johnstown Roosevelt upset Mead, the team Hartson had been wanting to beat since he was a little boy first putting on pads and a helmet, and it didn’t matter that only 150 fans could attend the game because of restrictions.

“Holy cow, they were just as loud as we needed them to be,” Hartson said.

Before long, the Johnstown faithful figured out a way to get around the rules. They stacked hay bales on semi trucks outside the stadium so people could see the game from a distance.

In October, Wasinger took some heat from teachers when he pulled the football players out of in-person classes and had them all learn virtually. That helped keep the Rough Riders on track for their on-field goals, and, as it turned out, the school had a COVID outbreak a few weeks later.

Roosevelt advanced to the school’s third state title game appearance. Team parents signed a petition to be allowed to attend the game in Pueblo, and once again, the state eased restrictions under pressure.

The Rough Riders lost to Durango, 14-7.

“These last few months have been some of the most memorable of my life,” Hartson said. “I feel a lot of remorse for those teams that don’t get to experience this.”

===

When L.A.’s Rough Riders finally got the go-ahead from the school district to work out together in November, Aldo Parral felt immense relief.

“For the first time in eight months, they got to be teenagers,” Parral said.

Just to work out with social distance, the players had to be tested weekly for COVID among many other strict protocols.

“I hadn’t been that happy in a long time,” said offensive tackle Benjamin Reyes. “Not being able to practice, it takes a toll. Being home all day, it’s really not for me.”

As the case numbers began to creep up around Thanksgiving, though, Parral knew they were operating on borrowed time. In early December, he had to tell his players that it was back to Zoom workouts every Monday to Thursday.

Now, once again, the Rough Riders can only watch the numbers and wait.

“I know the number is going to go up during Christmas,” Avalos said.

This Christmas in San Antonio, Dewayne Coleman was able to look back on a remarkable senior season that ended with a second-round playoff loss — and an invitation to play next year at nearby Division III Trinity University that he believes would not have come to him without this fall.

Coleman always saw himself as a leader, but playing this pandemic season forced him to prove it.

“A lot of people in my age group like to take things as a joke, and COVID is a big one,” Coleman said. “Some people just don’t believe that it’s real. There’s definitely been a lot of work for the leaders on our team, because if we don’t wear our masks or do everything perfectly then other people will feel like they have the right to not do it because Dewayne didn’t do it.”

For now, L.A. Roosevelt’s seniors aren’t being given that kind of growth opportunity. And for now, they don’t know if they’ll be able to play in “The Classic” against Garfield and avenge a decade’s worth of losing.

Parral boldly predicts that this would be their year.

“Even if we don’t have playoffs,” Reyes said, “as long as we have a ‘Classic.’ ”

“Most of my family went to Roosevelt,” Avalos said, “so playing in ‘The Classic’ is one of the best things that ever happened to me. Being told every year that we’re losers, that we won’t ever beat them again, I want to beat Garfield for my senior year and leave with a ring.”

The dream lives on, into 2021. All the Rough Riders need is a chance to make it come true.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.