Negro Leagues 100th anniversary sharpens focus on triumph amid racial inequality

- Share via

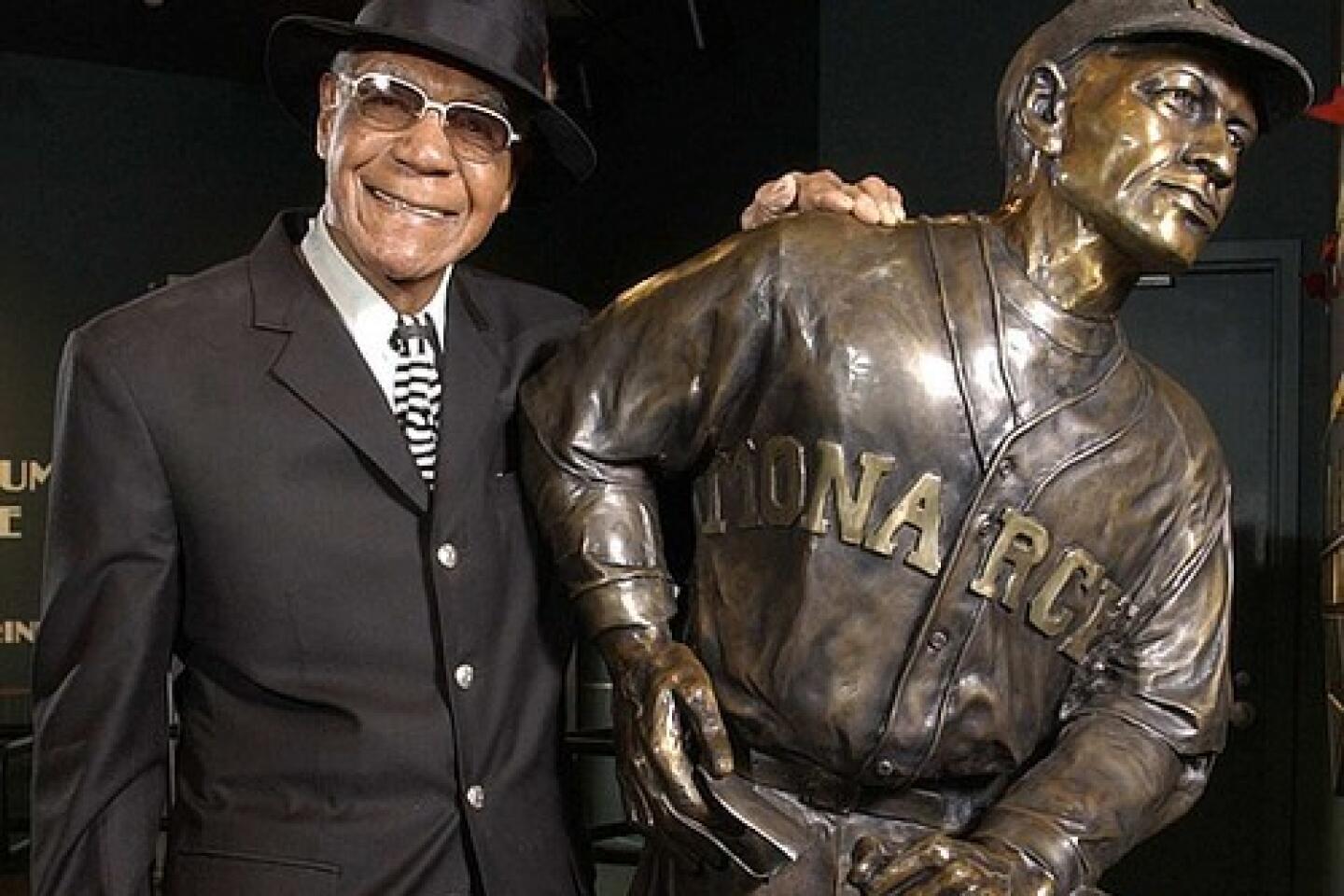

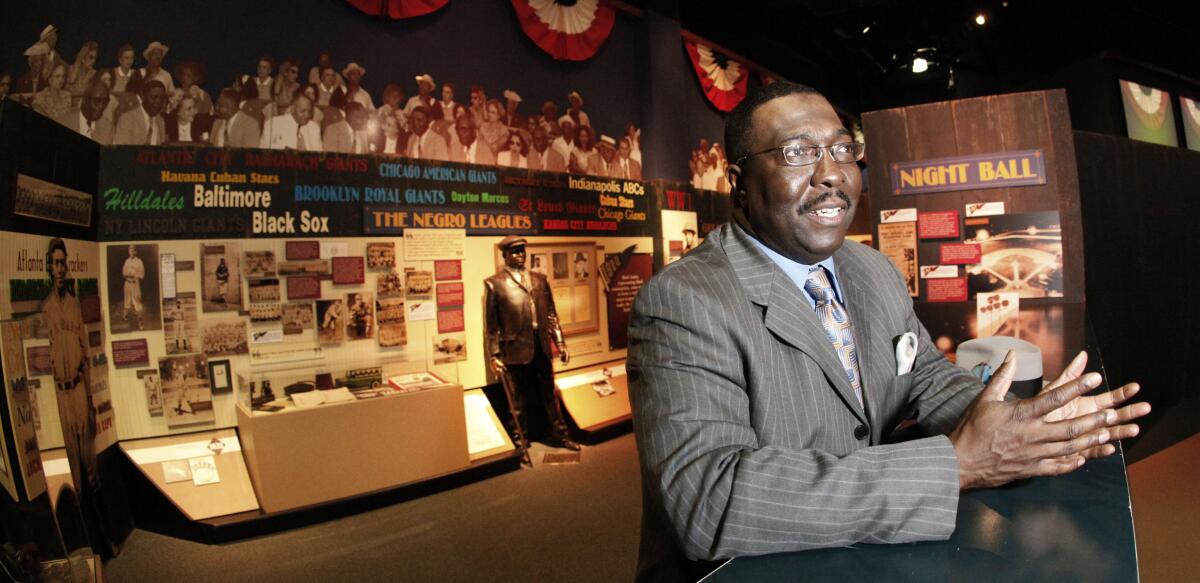

Every time Bob Kendrick steps out of his office, the President of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum gets to walk through the past.

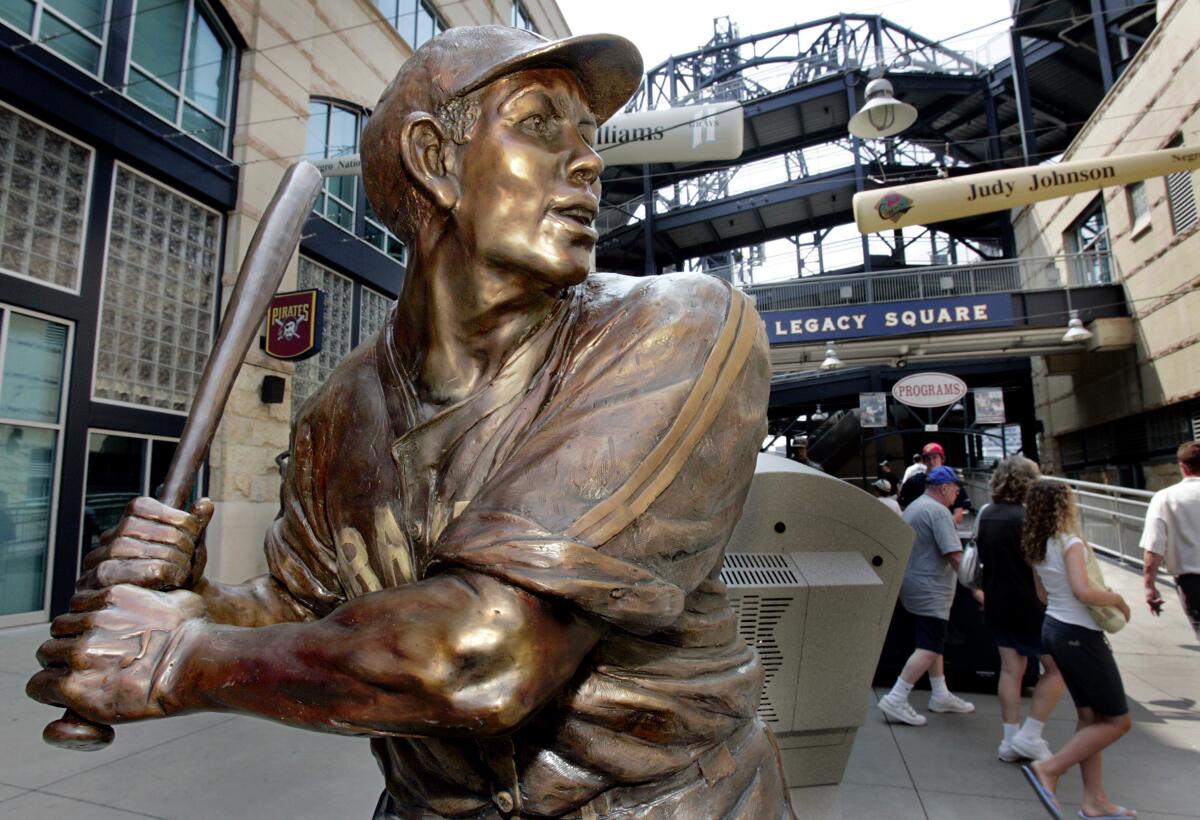

It’s one of his favorite parts of the job, perusing hallways adorned with old cotton jerseys of the Homestead Grays and Kansas City Monarchs and Pittsburgh Crawfords; strolling by statues of Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Buck O’Neil and other stars of a bygone era; delivering well-practiced dissertations to one visitor at a time.

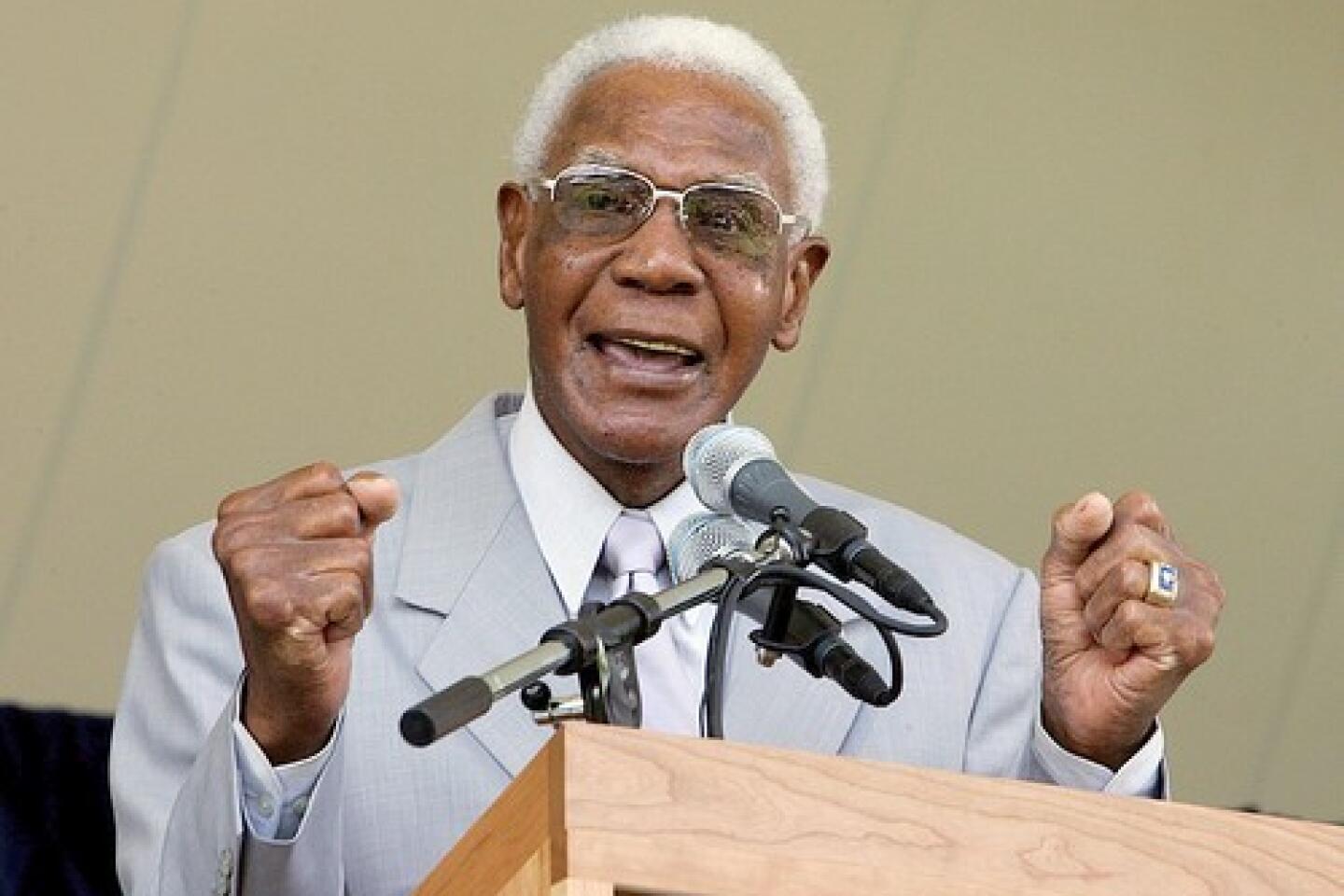

“This story is so much more than just a baseball story,” Kendrick said, his voice rising with emotion during a recent phone call from the museum in Kansas City, Mo. “This is a story of social injustice. It is a story of the civil rights movement. And it’s a story of overcoming all of that adversity stacked against them.”

He was hoping to amplify that message this summer, to celebrate the Negro Leagues’ 100th anniversary with several months of museum-organized events. The novel coronavirus pandemic derailed those plans. But the recent protests over social inequality have given him another type of megaphone instead.

His museum, he said, doesn’t just honor an often-overlooked history. It isn’t simply memorializing teams born out of segregation and the players who helped dismantle it. Now more than ever, he finds the Negro Leagues’ history reverberating today, connections to the present threaded within the story’s every stitch.

“The social justice upheaval we’re experiencing,” he said, “it magnifies and quantifies the value of our museum to a greater extent.”

Because every time Kendrick walks out of his office these days, he isn’t just walking through the past. He sees lessons applicable to the present, and ways to build a better future in baseball and beyond.

::

Negro Leagues historian Phil Dixon, 63, has published everything from books to photo albums to baseball cards over his decades of research, taking aim at misconceptions he feared distort the leagues’ legacy.

A common assumption, Dixon has found, is that the Negro Leagues were second-class, home to a few big stars that few fans ever got to see.

So, he and other historians have unearthed newspaper articles, photo archives, box scores — all manner of artifacts to paint an accurate picture of the leagues.

“I tried to break a lot of these long-held beliefs,” Dixon said. “Probably the greatest one was, ‘Too bad nobody ever saw these guys.’ That is a big lie.”

In reality, the Negro Leagues came to rival their MLB counterparts in attendance and in talent, Dixon said, overcoming the very discrimination from which they were created.

“It’s all built on one simple principle,” Kendrick explained. “You won’t let me play with you? Then I’ll create my own.”

As Black communities in Northern industrial cities grew during the Great Migration of the 1920s, which saw millions of African Americans flee terror and oppression in the South, Negro League clubs became a cultural touchstone, a place where inequality and injustice seemed to fade nine innings at a time.

“Baseball had been this catalyst that sparked economic growth in many urban communities across the country,” Kendrick said. “Essentially, wherever you had a successful Black baseball team, you can rest assured you had a thriving Black economy.”

There were ups and down. The Great Depression forced the original Negro National League, which had been guided by the “father of Black baseball,” Rube Foster, to fold. From 1927 to 1942, no official Negro World Series was held.

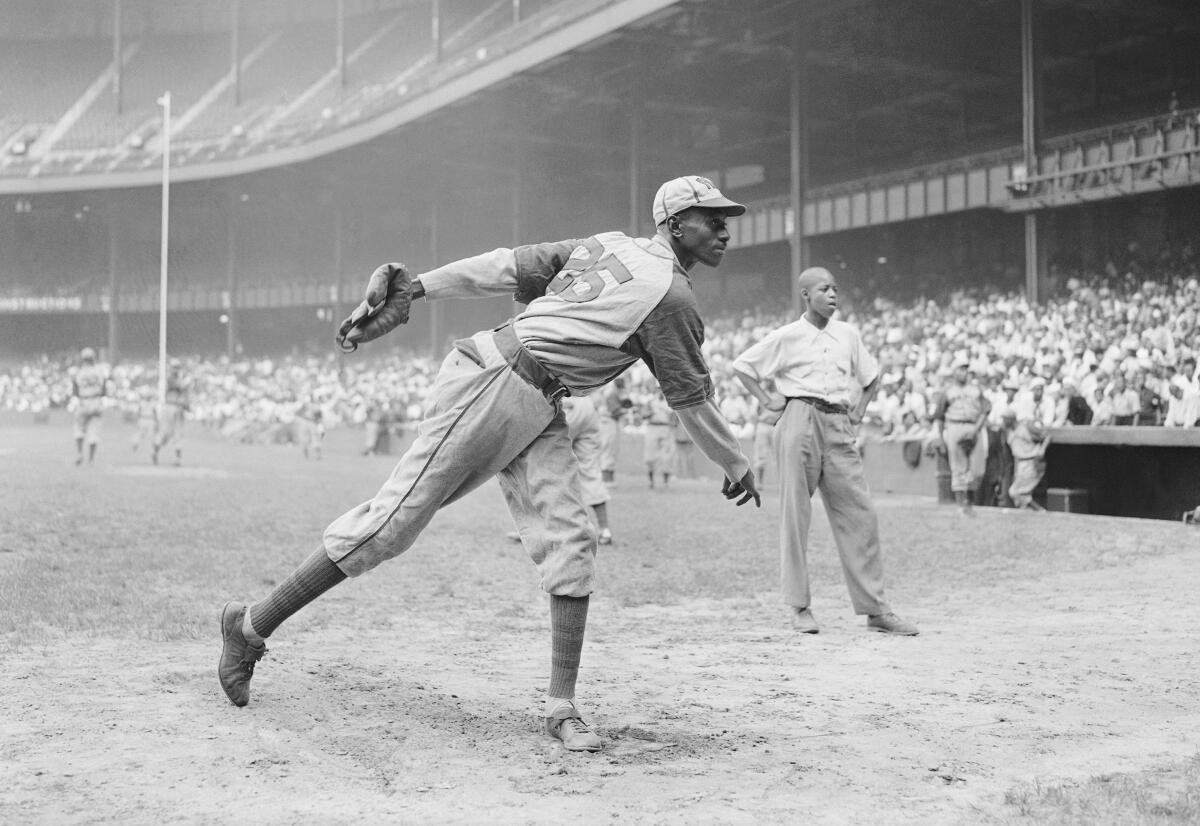

But Black teams pushed on, forming another Negro National League and a Negro American League in the 1930s while cultivating iconic players such as Paige (the whimsical right-handed pitcher with a blazing fastball and wicked repertoire of breaking balls), Gibson (historians can’t agree on the number of home runs he hit, though the Hall of Fame claims it to be “almost 800”), O’Neil (who became MLB’s first Black coach) and eventually Jackie Robinson (who played his lone Negro League season in 1945).

All that success ultimately became the leagues’ undoing. After Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier in 1947, most promising Black players began entering MLB’s minor league system, diluting the Negro Leagues’ talent pool. By the end of the 1950s, both major Negro Leagues were gone for good.

“It was good for the soul of our country,” Kendrick said of baseball’s integration. “It moved us in ways socially that we never fathomed. But it is bittersweet. There is always a cost to progress.”

In the Negro Leagues’ case, Dixon believes their reputation was diminished over time, thriving Black institutions mistakenly remembered as a low-tier afterthought.

“I think a lot of what we believe about the inferiority of Black teams is really social conditioning,” he said. “We are culturally conditioned with baseball history. A lot of the things we believe are how we’ve been conditioned to believe. It’s hard to break away from that.”

This is where Dixon draws parallels between the Negro Leagues and today, raising questions of racial biases and subconscious prejudices that have existed in baseball for the last 100 years — and in society for much longer than that.

“The more they portray the history, talk about the history of baseball, the way you portray that history gives a perception of racism,” he said. “I can’t explain it. The history has been very biased in its presentation.”

::

Jerry Hairston Jr. changed the topic unprompted.

The phone call with the 16-year MLB veteran who finished his career with the Dodgers in 2013 began with stories of his grandfather, Sam Hairston, a Negro League star who was the first African American to play for the Chicago White Sox.

Hairston Jr. laughed at the memories, recalling dinner table stories of Sam’s career (which began on an Alabama steel mill company team and culminated with his winning the Negro American League triple crown in 1950) and house visits from some of his famous former teammates.

“I’d be learning about the Negro Leagues in school,” Hairston Jr. said, “and go, ‘Wait a minute, [six-time Negro League All-Star] Double Duty Radcliffe, he was at my house a few months back.’”

Sam Hairston died in 1997. But his grandson cares deeply about his journey and what it said of baseball’s relationship with race.

“We appreciate the Negro Leagues more now,” Hairston Jr. said. “But the one thing I fear is that we don’t appreciate our Black players today. We talk about change, we talk about how we want to do certain things for the Black players. Well, how about having more Black people in front offices? How about having more Black coaches?”

His tone sharpened.

“We need to take more action. Don’t just tell us about it.”

Herein lies the paradox of professional baseball, a sport that simultaneously integrated and diversified its player pool without doing the same to its front office, ownership or league executive ranks.

While roughly 40% of MLB’s players are of color, according to a 2019 racial and gender report card published by the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sports, the league has just six minority managers, four minority general managers/heads of baseball operations, and one minority owner (the Angels’ Arte Moreno).

MLB’s inclusion of Black players and executives is even worse. Only 8.4% of players on 2019 opening day rosters were African American. And until the Houston Astros’ hiring of Dusty Baker this offseason, the Dodgers’ Dave Roberts was the league’s only Black manager.

“Baseball has been at the forefront of social change in this country,” said Kendrick, the Negro League Museum president. “Yet, in some ways, it has suffered from some of the same things it actually helped preach.”

Kendrick traces the start of the problem back to the dissolution of the Negro Leagues.

“All of these Black owners no longer owned teams,” Kendrick said. “You don’t really see many African American general managers. You had all of that in Black baseball when Black baseball had its own business. You had Black managers and Black coaches and team positions — they were fulfilling every aspect of the business of the game of baseball. And we lost that.”

The diversification of MLB’s non-playing roles has been slow and limited ever since.

“We saw the field integrate,” Kendrick said. “The hierarchy of our sport really did not get that same transformation.”

::

When Tony Reagins, MLB’s Executive Vice President of Baseball and Softball Development, convened his staff for one of their recent weekly Tuesday meetings, he planned to only briefly acknowledge the Black Lives Matter protests over social equality.

The cause resonated with Reagins, who became MLB’s fourth Black general manager when promoted by the Angels in 2007 (a position from which he resigned in 2011). He wasn’t sure, however, where the conversation would lead within his unit of the league’s office.

Two hours of tears, thoughts and talking later, Reagins realized what much of society is seemingly coming to understand. George Floyd’s killing at the hands of a police officer has wrought a newfound awareness of injustice, an increased appetite for change. This time, not even the baseball world is shying away.

“Individuals really opened up about their experiences,” Reagins said of the meeting. “Racism. Prejudices. Biases. All of that came into play. It really allowed us to look deep into who the individual was, and look deeper into ourselves. To verbalize your thinking out loud, it brings a different perspective.

“That’s a big part of what needs to take place, is having the conversations.”

Such conversations are the ones Negro League historians wish the sport had decades ago, when it could have diversified the culture — and not only the rosters — of America’s pastime. Instead, as former big leaguer and current baseball analyst Doug Glanville can attest, race became a topic most Black players felt they couldn’t address.

“It’s hard as a Black player, when your experience is taboo,” Glanville said. “Sharing what is absolutely eating away at you is something you have no forum for and no place to talk about.”

Kendrick noticed the same thing, especially after hosting a recent town hall discussion with six current big leaguers.

“Inevitably, they’re going to walk into a locker room without a lot of people who look like them,” he said. “Sometimes, they may be the only African American in that locker room. That’s why I think it’s really important that baseball be out in front of this cause. Because what it does is, it helps even more so demonstrate that this is not an African American cause. This is something that all Americans need to be on the same team, trying to tackle this issue. And when our national pastime is involved, it does serve as a bit of an awakening.”

Kendrick’s hope is shared by others in the sport who are optimistic that baseball, with its complicated and at-times porous history of racial inclusion, can be a leader in promoting profound change. Players and teams, including the Dodgers, have spoken out.

“For us to change as a society in a large sense, you need everybody on deck,” Glanville said. “All kinds of voices can add to this conversation and add to this change. . . . We’d like to see change happen across the board when it comes to who is participating and making those changes. And baseball is uniquely situated with a great opportunity.

::

Before Kendrick hung up the phone, eager to return to the museum halls and begin interacting with patrons (socially distanced, of course), he had one more point to make.

So often, he said, stories of social change and racial injustice are wrapped up in pain and sorrow, failures and shortcomings. The Negro Leagues’ history is different, a triumphant reminder that the push for equality — in baseball or otherwise — hasn’t been all bad.

“You look at the civil rights story in general, much of it is so painful,” he said. “It’s African Americans being sprayed by water hoses and dogs being unleashed on us. These episodes of being beat down by police.

“But when you come to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, it’s an entirely different look at something that is a civil rights story. It’s triumph over it, and it’s proud. You can’t only see my pain. You have to see my triumph as well as we try to plant the seed for equality in our country.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.