As more players test positive for coronavirus, can MLB be trusted to protect them?

- Share via

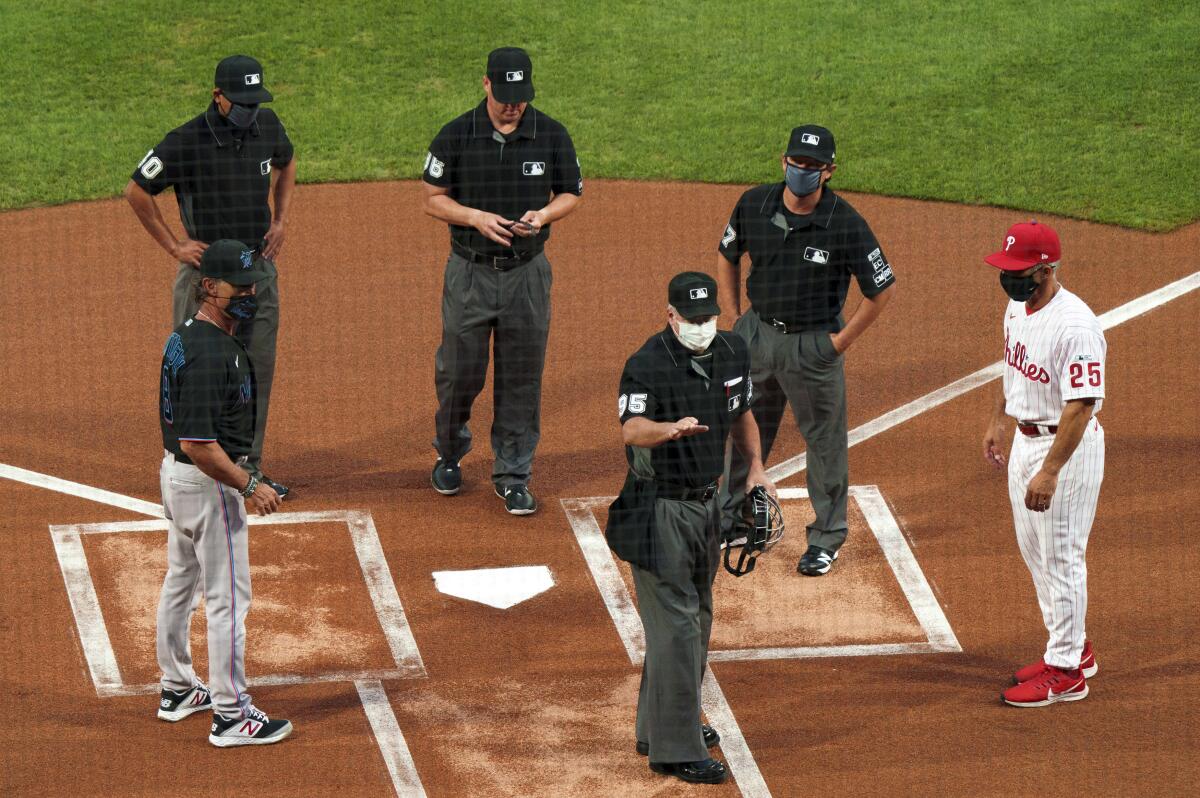

The Miami Marlins, with half the players on their roster infected by the coronavirus, aren’t playing for at least a week. The Philadelphia Phillies, the last team to take the field against the Marlins on Sunday, aren’t playing for at least four days.

In Milwaukee, Ryan Braun shared the vulnerability felt by his peers. He is a baseball player, and a six-time All-Star at that, but he also is a husband and father.

“I don’t feel comfortable with where we’re at,” Braun said. “There’s real fear and anxiety for all of us.”

By Sunday, the first-place Marlins will have played three of their first 10 scheduled games. They have no good idea when or where they may play again.

As Major League Baseball plows on through a pandemic, the players’ perennial distrust of the owners surfaced with regard not to money, but to life.

When Washington Nationals manager Dave Martinez gathered his players and asked who wanted to play this weekend in Miami, where the virus is raging in the community, one hand went up. That vote never should have needed to be taken.

The Miami Marlins will not resume play until at least Monday. The Phillies won’t play until at least Friday.

The Marlins and Phillies should have been shut down on Monday, not Tuesday, and the 24 hours in between left room for some players to wonder whether MLB made the right call only after epidemiologists from coast to coast called out the league on what appeared to be its dangerous ways.

By Monday, 11 Marlins players had tested positive. You didn’t need to be an epidemiologist to call that an outbreak, and yet there was commissioner Rob Manfred on MLB Network, saying he hoped the Marlins could play on Wednesday.

“A team losing a number of players that rendered it completely noncompetitive would be an issue that we would have to address,” Manfred said.

In that same interview, Manfred denied the contention of the Dodgers’ David Price that “players health wasn’t being put first.” Yet there was the commissioner, the same man who angered players this spring by referring to the World Series championship trophy as a “piece of metal,” talking about the possibility of shutting down the Marlins in terms of competitive integrity rather than player health.

In fairness, Manfred ultimately did the proper thing, keeping the Marlins and Phillies off the field until testing could provide a clearer picture. No one test, positive or negative, offers proof. And you and I could be infected at the same time, but you could test positive three days before I do.

Competitive integrity should be the least of the league’s worries, with the regular season at 37% its normal length and the postseason expanded to 16 teams. Who cares if the Marlins play 50 games or 60?

“If everyone doesn’t play 60 games, I think that’s all right,” Phillies manager Joe Girardi told MLB Network Radio.

The Marlins and Phillies did not play Monday or Tuesday. The New York Yankees and Baltimore Orioles were rerouted to Baltimore. The Phillies could return Friday, against the Toronto Blue Jays.

That would be a home game for the Blue Jays, in Philadelphia, because the government of Canada refused to let the Jays play in Toronto, and because the government of Pennsylvania refused to let the Jays play in Pittsburgh.

The Marlins are scheduled for home games next week, but the mayor of Miami suggested Tuesday he would like the team to quarantine for 14 days upon its return home.

The virus is bigger than baseball. The league does not believe it bungled its response, as it handled the immediate crisis on Monday and longer-term issues on Tuesday, after four more Marlins had tested positive. And perhaps MLB got lucky this time, with the outbreak limited to one team.

In Milwaukee, Braun said the Brewers had taken tests in one city, then got on a plane to fly to another city, where the test results would be available.

At least 13 members of the Miami Marlins tested positive for COVID-19, yet baseball soldiers on. What would be the breaking point in MLB and other sports?

“The plane felt really dangerous,” Braun said.

Braun used the words “disturbing” and “upsetting” to describe his emotional response to the Marlins’ outbreak, in addition to fear and anxiety.

“Those are true feelings and emotions,” the Dodgers’ Joc Pederson said, “and that’s why some people have elected not to play this year. They’re real. The health concerns, I know some people think are fake, but they’re extremely real. You see the people on the front line fighting, doing their best to save lives.

“It’s scary. We’re definitely taking a risk by participating. That’s why we’re trying to be good teammates — to us, and the umpires and the opposing teams — to hold each individual accountable to keep everyone safe.

“The last thing you’d want to do is not be able to see my family or my loved ones — I guess, if you died, it would be the worst-case scenario — but for months or weeks, because of a quarantine issue.”

In baseball, a worst-case scenario is an injury, or a slump. In pandemic ball, it is indeed death.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.