The NFL. NASCAR. George Floyd has inspired a sports reckoning too. Will it last?

- Share via

When it comes to playing pickup ball, I’m a habitual sizer-upper. As soon as I step onto the court and a guy picks up the rock, I’m asking myself a hundred questions: Which hand is the dominant one? Where do they like to shoot? Are the feet, hips and wrist aligned? How’s the footwork? What shoe is he wearing?

But the most important question?

How’s the follow-through? That’s where you learn intent. An insecure shooter has an inconsistent follow-through. Even if a guy hits a jumper, his finish lets me know whether he thought the shot was going to fall and, more importantly, the chances of him doing it again.

In announcing an immediate ban on the Confederate flag, NASCAR took a shot — a really big shot — and that’s a great step forward. But now it’s time to parse the follow-through because let’s be real: There aren’t a whole lot of fans for NASCAR to turn away. What happens once the country is fully open and RVs start showing up with Dixie flapping in the wind? Will NASCAR be as diligent in enforcing its new rule as it was bold in announcing it?

It’s all in the follow-through.

The main concern of black people right now isn’t whether they’re standing three or six feet apart, but whether their sons, husbands, brothers and fathers will be murdered by cops.

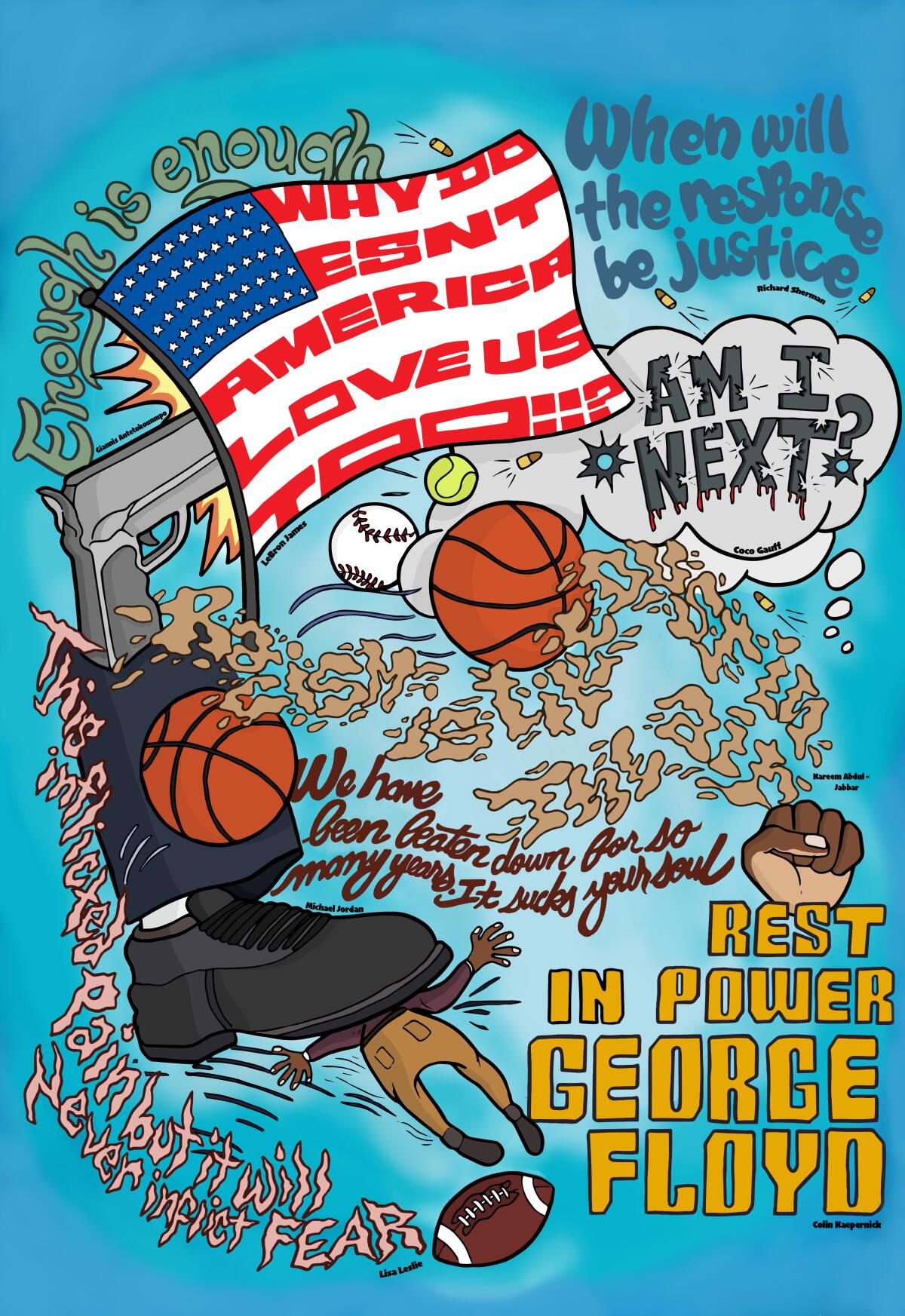

And just as the concept isn’t unique to basketball (think golf swing, pitching motion), the pressure to follow through on bold affirmations that Black lives do matter doesn’t fall solely on NASCAR. Much of the sports world spent last week beating its chest about fighting racial inequality — a $250 million pledge from the NFL here, a lot of pretty statements printed on league letterhead there.

But now what?

“We have to throw away the old handbook,” said Tim Harris, the Lakers’ chief operating officer. “The goal of the old handbook was to win the press conference. You know, make a statement, write a check, and move on ... be non-racist.

“In 1992 when the riots hit, winning the press conference was front and center on a lot of people’s minds. But we have to stop approaching a societal problem with a sports business solution: slogan, logo, market, sell. Those days are over when it comes to racism. We have to figure out what we can do to move from being non-racist to anti-racist.”

“We have to stop approaching a societal problem with a sports business solution: slogan, logo, market, sell. Those days are over.”

— — Tim Harris, Lakers chief operating officer

In the week after the George Floyd killing and global protests that followed, the Lakers sought the counsel of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who shared his well-documented history on the topic with players and employees in a lengthy Zoom conference on June 3. Team executives also spoke with UCLA sociology professors to gain a better understanding of the intricacies of systemic racism and how and where the franchise should direct resources.

“We support what the players are doing,” Harris said. “Obviously what LeBron [James] has been doing is fantastic. But then we need to look at what the franchise is doing in this space and what’s going on within our walls. Are we engaged in bad practices internally and if so, what are we going to do about it?”

In mentioning James, Harris was referring to the formation by James and other athletes this week of More Than A Vote, which will assist the Black community in combating voter suppression. The venture attracted the attention of Rep. Karen Bass (D-Los Angeles), who introduced a police reform bill this week in the House that would give the federal government greater power to investigate and prosecute misconduct by law enforcement.

“Athletes and teams can play an incredibly important role and their involvement is so needed right now,” Bass said. “The reality is, for years the Black community has been talking about this issue and really not been believed. Even with cellphones to capture the altercations, people didn’t want to believe it. But nothing can galvanize public opinion like the people they admire, [which is why] athletes are very important in all of this.”

What happened to George Floyd, Christian Cooper and Ahmaud Arbery shouldn’t be characterized as sad anomalies, columnist L.Z. Granderson writes.

As are owners, the vast majority of whom are rich and white, and have not been shy about using their political capital to get stadiums built or hosting $100,000-a-plate fundraisers for their favorite 45th presidential candidate. A social media platform is one form of power. Billions and access to lawmakers is another. Which is why the silence of so many of them is so deafening.

It is also why Steve Ballmer’s commitment to change is equally as loud. The Clippers owner convened a franchise-wide Zoom meeting on Thursday, some 200 Clippers employees in all, in which I was a speaker. He was vocal in the conversation, uninterested in winning the press conference, pressing for specifics about criminal justice reform and how to effect meaningful long-term change. He displayed what Maya Moore — who left the WNBA at her peak to help free a man wrongly convicted of burglary and assault from prison — would call “cultural humility.”

“Sports can help to lead in challenging us as a nation to grow in cultural competency which will lead to cultural humility,” Moore said. “Taking the time to grow in understanding someone else’s cultural perspective will allow for greater appreciation and communication between people of different backgrounds.”

Every team in the L.A. sports market has been in meetings these last two weeks trying to chart a path forward. The question for the Dodgers, Lakers and Clippers, for the Rams and Chargers, is the same question I would pose to NASCAR: What’s going to happen when games are being played again? Racism didn’t quarantine during the shutdown. Quite the opposite. What’s to prevent the sports world from dusting off that old playbook Harris said needs to be thrown out? You can be certain that athletes will carry the message of the protest forward. They will be loud. They will kneel. They will make White America feel awkward, and inconvenienced. Will their employers follow?

“Are we going to walk that walk?” Harris said. “God, I hope so. I really do. That’s why we’re attacking this thing very differently than before. The easiest and laziest thing to do is write a check but that’s treating the symptoms not the disease.”

Harris is talking about the follow-through.

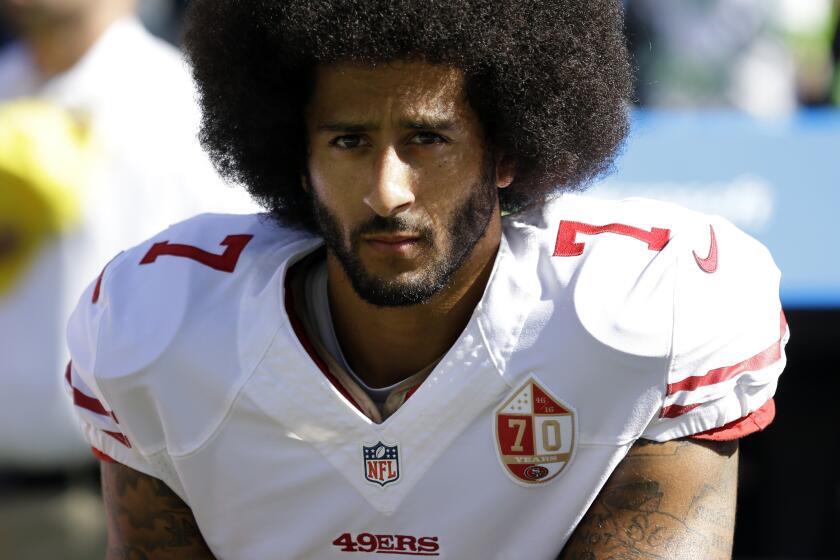

After George Floyd’s death, the NFL apologized for not doing enough to fight racial injustice, but it needs to restore what it stole from Colin Kaepernick.

So, too, is Anthony Lynn.

“I look at the National Football League and I see people from so many backgrounds and races come together like a family and we pull together in one direction,” the Chargers coach said. “How do we do that in society? I don’t know if it can be done. I just know in my life I’ve been on teams with people who were racists ... and they’ve come around to becoming really good teammates and really good friends.”

That may come across as some sort of Pollyanna nonsense. Like the NFL’s version of the film “Green Book.” But Lynn, one of three Black NFL head coaches, is not an out-of-touch apologist, he just knows what can happen when hate and fear is eclipsed by empathy and understanding. You can pass legislation to minimize the damage caused by racism, but the way to change hearts and minds is through interpersonal interaction.

The Chargers coach shares his thoughts on George Floyd’s death, his relationship and experience with law enforcement and Colin Kaepernick.

No current athlete has been more courageous in his test of that theory than NASCAR’s Bubba Wallace, who implored the sport to ban the Confederate flag. Not only did he risk his career, he risked his personal safety. Remember how many Confederate flags we saw during anti-quarantine rallies around the country. The Athletic’s Jeff Gluck wrote last week that Wallace “acknowledges he has to be worried about personal safety” and that “he won’t just be able to take an impromptu trip into the infield and knows he may have to watch his back at tracks now.”

Wallace is relying upon those around him in the sport to join him in taking — and maintaining — an anti-racist stance. Whether NASCAR follows through on its vow to change will depend on the support of Wallace’s fellow drivers too. And not the kind of support that comes from a retweet but the kind that stands with him while some fans boo, make threatening remarks, maybe even spew the N-word.

This is what makes Wallace and NASCAR’s actions so shocking to a lot of people, myself included. We know what that flag stands for and how dear a lot of people hold it. As sports continue to open up, we’ll see what it stands for and what it holds dearly.

Strong statements and gestures during a movement and protest at a fever pitch are a fine start. But I’m here for the follow-through.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.