How Houston coach Dana Holgorsen used redshirts to tank in college football

- Share via

HOUSTON — Under certain circumstances, professional sports franchises can openly accept defeat and get away with it. Even an Olympic badminton team has tried to lose in the name of winning a bigger prize later. But the assumption in college football is that every school, from Division I’s “Power Five” to Division III, is doing all it can to win each time it plays.

That custom — and the University of Houston’s 86-44 record in the previous decade, better than state powers Texas and Texas A&M in that same period — was what brought offensive guard Justin Murphy here for his final season of college football after previous stops at Texas Tech and UCLA. Houston’s first-year coach, Dana Holgorsen, had sold him on the opportunity to win immediately on a team led by dynamic senior quarterback D’Eriq King.

Four months after joining the program, Murphy, a friendly native Texan, sat in the Houston student union, his football career over prematurely, posing the question he’d been asking since the Cougars lost a heartbreaker to Tulane on Sept. 19 to start the season 1-3.

“If we had started 3-1, would they have done this?” Murphy said.

He knows the answer. No, if the Cougars had been 3-1, Holgorsen would not have encouraged his best players, including King, to use the NCAA’s year-old rule allowing players the option to redshirt a season as long as they haven’t played in more than four games.

But Murphy felt it important to hold accountable Holgorsen and Houston, which is perpetually waiting for that elusive invite into a “Power Five” league.

Murphy’s frustration boiled over Oct. 10, after he and the program had parted ways because of his nagging knee injury and several incidents of him openly challenging the redshirt decisions in the locker room. Murphy went to Twitter to air his grievances.

“My name is Justin Murphy,” he began from his account, @JMurphy_73. “And according to sources I am no longer a part of the 2019 Houston Cougar Football Senior Class. A senior class that is the first group to experience a head coach and administration to actively tank a football season.”

Holgorsen declined to comment for this article through a Houston athletic department official. A representative for school president Renu Khator could not be reached.

According to Murphy, on the Monday after a 38-31 loss to Tulane, he heard from starting center Braylon Jones, a senior, that Jones had been asked by Holgorsen to redshirt the season. Taken alone, that made sense to Murphy because Jones was battling a shoulder injury.

But later, during a team meeting, Holgorsen “opened up with, ‘We’re going to make redshirting a good term and not a bad term,’ ” Murphy recalled.

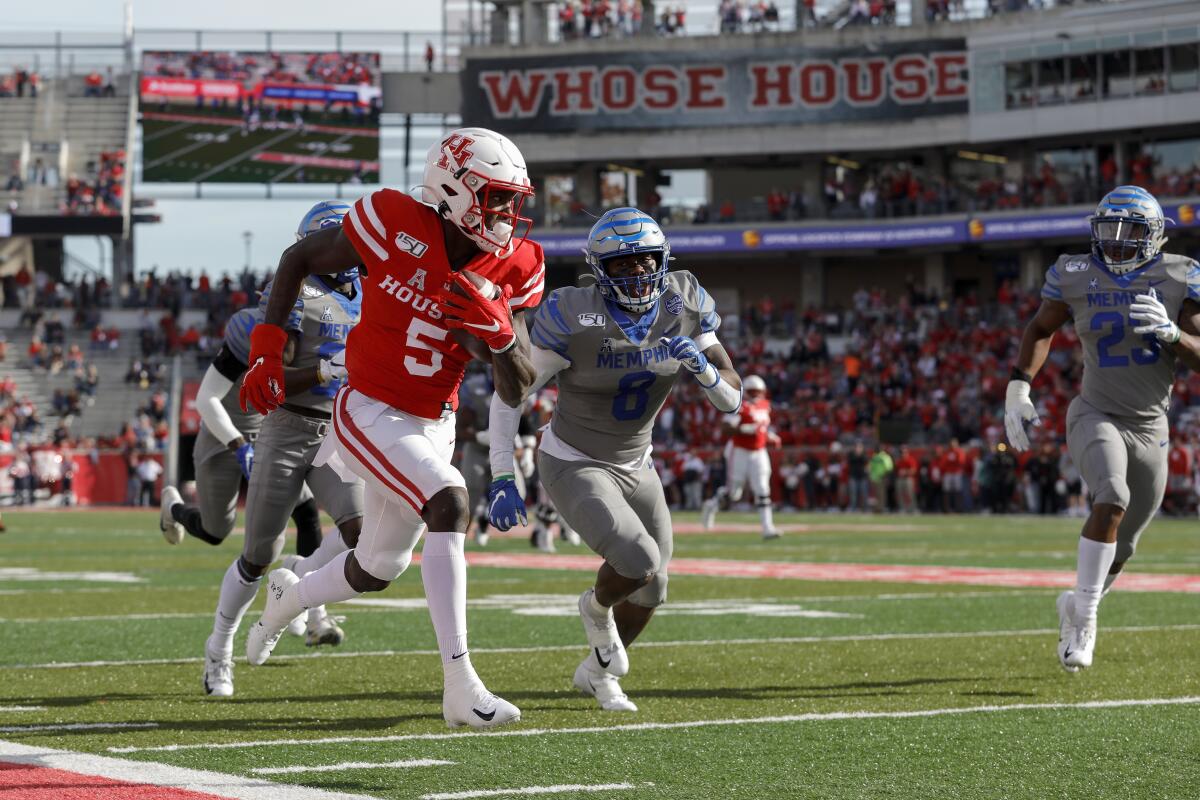

Word had already begun to leak that King, the electric dual-threat quarterback who combined for 50 passing and rushing touchdowns in 2018, had decided to redshirt the season after playing in four games.

A report surfaced that King’s intention was to transfer to another school in the offseason, but Houston would soon officially announce that King and senior wide receiver Keith Corbin were going to redshirt 2019 and come back to Houston for 2020, effectively taking a mulligan on their final season as Cougars.

Five games to watch during Week 14 of the college football season, including the Iron Bowl between Alabama and Auburn and Michigan vs. Ohio State.

At the team meeting, Murphy said, Holgorsen made it clear that any other players who were interested in redshirting should feel free to come forward. Murphy, playing his fifth season of college football, was shocked. Until then, he had seen each team’s goals proceed the same way:

It starts with the hope of competing for a national championship — in Houston’s case, that meant beating Oklahoma in its opening game and then Washington State in game three. Then, once that dream dies, the goal becomes winning the conference — Houston still could have won the American Athletic Conference after the Tulane loss. When eliminated from a conference title, teams then shoot for a bowl berth, which requires at least six wins.

“Then, after you get knocked out of bowl eligibility,” Murphy said, “the goal shifts to developing as a player. But, you know, obviously you still want to win the games.

“Well, here at the University of Houston, they skipped a step.”

President Khator has been bold in saying Houston belongs in the “Power Five,” and the school has shown it will do just about anything to get there. Striving to win every game this season and ending up 6-6 does nothing for that pursuit, while saving up for 2020 with King and other talented players offers the potential for the Cougars to earn a New Year’s Six bowl berth.

“She knows that if UH wants to be at the status she wants it to be, athletics is the way,” said Jhair Romero, a sophomore at Houston and the sports editor of the Daily Cougar, the school’s student newspaper. “That’s how your school grows. They’re going to continue to push for the ‘Power Five.’ This year isn’t the best year to look at, but they’re kind of building a resume for that.”

Houston has played in a bowl game in 13 of the last 16 seasons, but that is no longer good enough. Khator reportedly once told faculty and staff at a holiday party that “winning is defined at University of Houston as 10 and 2. We’ll fire coaches at 8 and 4.” Houston followed through on that promise by replacing coach Major Applewhite with Holgorsen after going 8-4 last season.

Houston is paying Holgorsen $20 million over five years, the largest “Group of Five” contract in history, and the Cougars play in a five-year-old, $128-million on-campus stadium. So, given the deep desire to permanently join college football’s elite, the reason the 2019 season was so easy to sacrifice isn’t clear.

The NCAA’s new redshirt rule was intended to give players more control over their career by making it less likely they would waste a year of eligibility by appearing in only a couple of games. The byproduct for coaches was more flexibility in roster management.

An NCAA official responded to an inquiry about Houston’s unique use of the redshirt rule by saying that the Division I Football Oversight Committee does not assess major policy changes until two seasons are complete. This is the second season for the rule.

“That’s the kind of stranglehold these coaches and these universities have with their players. And that’s why you don’t see people come out and say these things openly.”

— Justin Murphy, former Houston offensive guard

Eric King, D’Eriq’s father, said that his son entered the season with the rule in the back of his mind.

“I’d be lying to you if I said we didn’t know the rule was there,” Eric King said. “We didn’t know how it would shake out, we didn’t intend to use it at all, it just happened that way.”

Eric King said that Holgorsen initiated a meeting with the King family after the loss to Tulane because “he sensed something was wrong. He definitely approached us with it.”

Eric King agreed with Murphy’s notion that Holgorsen elected to “tank” this season. He said that other players were sitting out this season who could have helped the team even before it fell to 1-3. He also said that he has made his critiques clear to Holgorsen.

Tanking has never happened in college sports because there has never been an obvious benefit to sitting your top talent like there is in professional leagues, which award the worst teams with the best draft picks. Plus, it goes against the NCAA’s purported cultural aspiration, to use collegiate athletic competition to help mold young adults into productive professionals and citizens.

Houston didn’t break any rules. However, did it damage a long-held competitive covenant among its players?

Justin Murphy was the only one who was willing to take a stand. He said he was painted by Houston coaches as a “locker room lawyer,” a purveyor of unwanted negativity.

“That’s the kind of stranglehold these coaches and these universities have with their players,” Murphy said. “And that’s why you don’t see people come out and say these things openly.”

Recently, Murphy went back to the Houston team facility to talk with the training staff about his knee, and some of his former teammates approached him.

He felt validated by the message they had for him:

“You’re gonna be a legend.”

Since UCLA linebacker Krys Barnes started football, he knew his plans for each fall. Football was always his focus, although his future is hazy after Saturday.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.