- Share via

It wasn’t just the massive chunks of ice breaking loose, crashing down. New waterfalls appeared, tumbling from surrounding cliffs, as if the frozen terrain were melting away.

With the 2022 Winter Olympics drawing near, top U.S. skiers and snowboarders traveled to the Swiss Alps in early fall, gathering in the village of Saas-Fee for offseason training on the year-round ice and snow of an adjacent glacier.

This time looked different from previous camps.

“Definitely a weird thing at play,” said snowboarder Red Gerard, the defending gold medalist in men’s slopestyle.

Teammate Jamie Anderson, a two-time Olympic champion in women’s slopestyle, called it “pure physical testimony to how gnarly climate change is.”

Mammoth’s culture and environment has produced many of the top U.S. snowboarders, and some of them will be competing for gold at the Beijing Olympics.

American athletes headed for Beijing might not be formally educated in climatology or conversant in all the relevant political arguments. Their concerns might not compare to widespread heat waves, droughts and flooding. But they have a ground-level view of climate trends and can see firsthand the impact of global warming.

A recent Canadian study predicted that, by the end of the century, nine of the past 21 Winter Olympic cities might not be cold enough to reliably host downhill races, biathlons or halfpipe competitions. The list includes Palisades Tahoe (formerly Squaw Valley) and Vancouver.

Elite competitors say they are already dealing with shorter winter seasons and deteriorating conditions on the international circuit.

“We’ve definitely had some challenges over the last couple years,” aerial skier Winter Vinecki said. “We’ve gone to sites, and normally we would have snow, but it’s been raining. And then there were some days we were jumping on snow in the pouring rain.”

Like other hosts, Beijing will hold a divided Winter Games, with indoor events such as figure skating, speedskating, ice hockey and curling played in urban arenas and snow sports taking place in distant mountain locations.

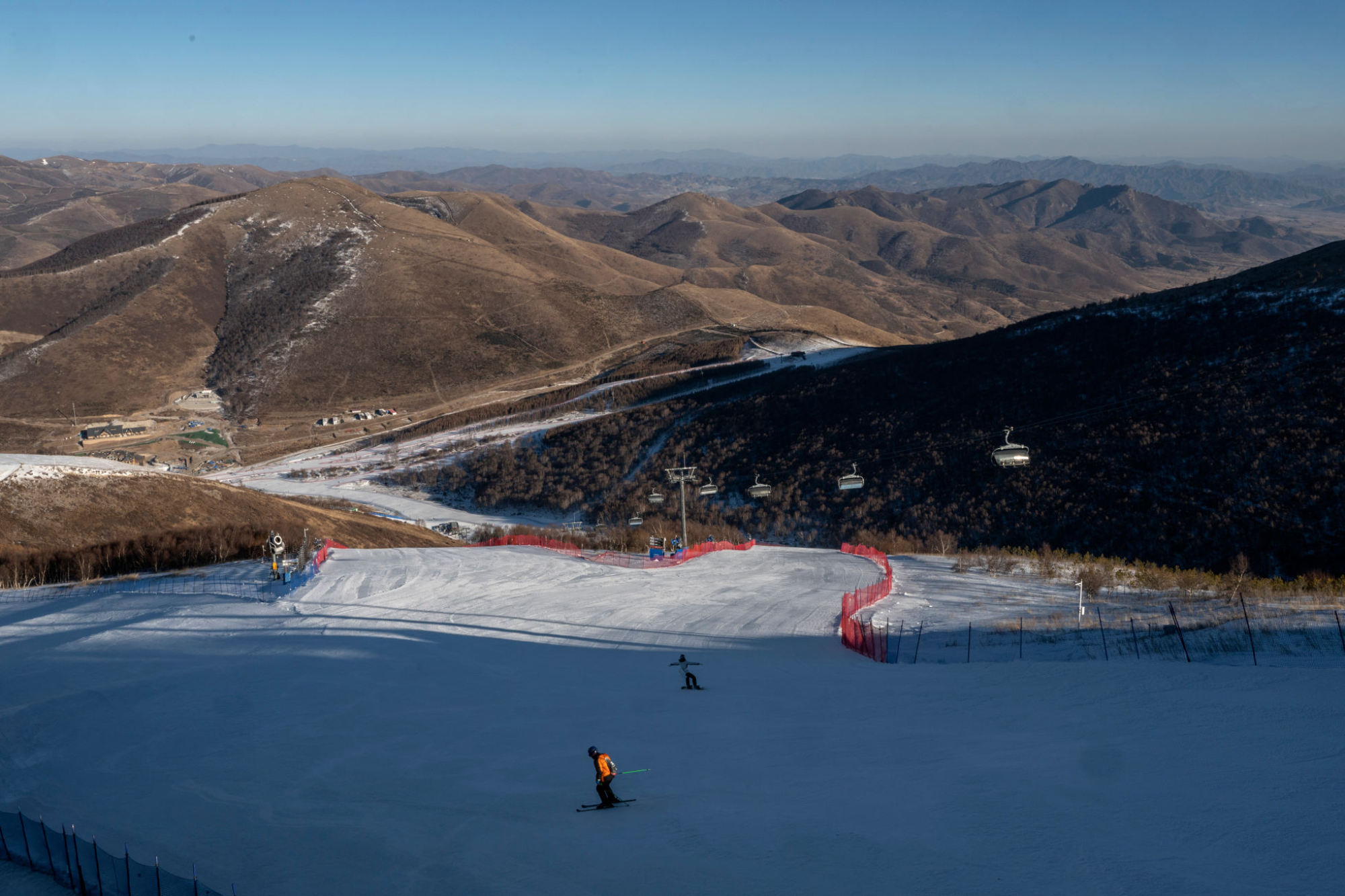

Though forecasts have predicted a cold winter for China, high-altitude venues in the Yanqing and Zhangjiakou areas are not expected to receive much precipitation. Chinese officials have launched a campaign to blanket ski runs and courses with artificial snow.

Man-made coverage played a role at previous Winter Olympics. Recent Paralympics in South Korea and Russia experienced unusually warm weather.

“Pyeongchang, it was mid-60s [degrees] to low 70s,” said Keith Gabel, a U.S. Paralympic snowboarder. “Same in Sochi, and those aren’t winter conditions necessarily.”

The International Olympic Committee deserves some blame for picking meteorologically questionable hosts. But that 2018 Canadian study, led by researchers at the University of Waterloo, isn’t the only warning that natural snow could become more difficult to find.

Earlier this month, calculations by NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration put 2021 among the six hottest years on record, elongating an eight-year stretch of record temperatures. Despite annual fluctuations, overall global temperatures have risen by 2 degrees Fahrenheit, or 1.1 degrees Celsius, since preindustrial times.

Scientists have repeatedly stated that fossil-fuel emissions are to blame and that effects will worsen globally if temperature increases exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“There are already changes in snowfall and precipitation types, snow versus rain,” says Twila Moon, a research scientist at the National Snow & Ice Data Center in Colorado. “Those changes have been seen very widely across the globe.”

Climate change has made Alpine and Nordic skiing increasingly dependent on technology.

Race organizers are efficient at blowing artificial snow and “farming” the real thing, storing it under cover and then moving it around to fill bare spots, but man-made surfaces don’t quite feel the same. Halfpipes are firmer and less forgiving when snowboarders wipe out. Downhill runs injected with water, a hardening procedure that makes them weather-resistant, can be icier, faster and risky at high speeds.

“I think we always just have to face whatever’s thrown at us and adapt,” U.S. skier Ryan Cochran-Siegle said.

Cross-country and biathlon events — winter’s version of the grueling marathon — have also been affected. They require less coverage but are held at lower elevations, leaving them vulnerable to snow lines receding up the mountain. There have been whispers of inching upward into more snow. And thinner air.

“Elevation is a very touchy subject with a lot of Nordic athletes,” U.S. Paralympic athlete Jake Adicoff said. “It would not feel good to go up another 2,000 feet from here and racing that would be, I don’t know, just not ideal.”

Biathlete Clare Egan says “the altitude limit exists for a safety reason, as far as I know, which is that it can be so stressful on the body after a certain limit that it’s not safe.”

Looking to the future, current Olympians wonder if the next generation will have enough snow to develop their skills. There is concern about the viability of recreational skiing because local resorts don’t always have the same degree of snowmaking afforded to top competitors.

Karla Schleske knows Mexico has had very few Winter Olympic athletes, but she’s determined to overcome history and age to achieve her goals.

“I think this is something that many people who spend time outdoors can relate to,” scientist Moon said. “We can feel those influences of drought, wildfires and changes in waterways. Here in Montana, it’s hunting and fishing.”

Some U.S. team members have been motivated to take personal action.

Freestyle skier Maggie Voisin encourages people to recycle and sign petitions that support environmental legislation. As a two-time Olympian in biathlon, Susan Dunklee spent prize money from a silver medal at the world championships to install solar panels on her house. She recently bought an electric vehicle.

“It’s easy to get discouraged when you’re thinking about the whole climate-change issue,” Dunklee said. “But when you look at sports, you see underdogs pulling off amazing things all the time … and we, as individuals in a global community, we might be underdogs in this struggle, but we’ve got to keep fighting and keep believing.”

Thoughts of global warming will probably fade with the start of competition in Beijing, the focus shifting to gold-medal performances. Large turbines resembling yellow jet engines — computer-controlled to switch on and off depending on weather conditions — have been spraying artificial snow at Olympic venues for weeks.

“I have faith that China is going to take it very serious and have plenty of snow there,” Paralympic skier Andrew Kurka said. “So there won’t be rocks or anything poking up in the course.”

Still, adapting to climate change has become part of the game. Winter-sports athletes know they face an uncertain future, a point driven home by their training camp in Switzerland.

“In Saas-Fee, up on the glacier, you can tell a huge difference with what it looks like now compared to even five years ago,” slopestyle skier Alex Hall said. “There’s a lot of melting going on.”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.