- Share via

The girl couldn’t make it across the pool.

Midway through the 25-meter journeys at the Palisades Swim and Tennis Club in Cabin John, Md., she’d grab a lane line and catch her breath like so many other 6-year-olds figuring out how to swim. Then the windmilling to the other side resumed.

She had a smile that seemed bigger than her diminutive frame, swim cap pulled over her ears and enthusiastic post-race analyses captured on home movies.

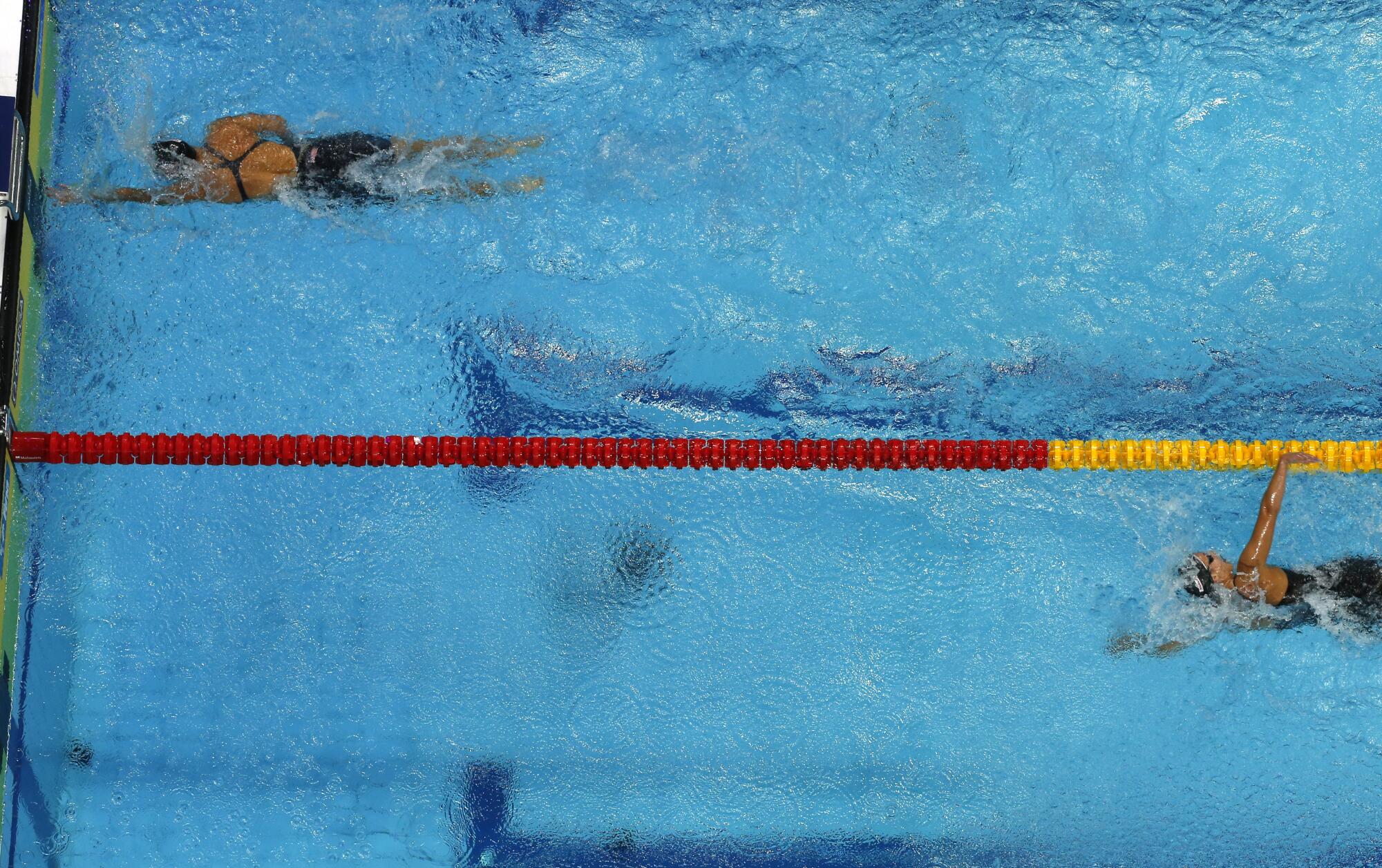

Eighteen years later, Katie Ledecky is the world’s most dominant freestyle swimmer. The biggest question when she knifes through the water usually isn’t whether she’s going to touch the wall first, but how many body lengths she’ll be in front of the second-place finisher.

“Katie Ledecky is doing what Katie Ledecky does!” the public address announcer shouted last month as she completed another convincing victory during the U.S. Olympic swimming trials in Omaha, Neb. “Do not let it pass over you.”

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

The victories, the records, the head-shaking performances in which her only competition is the clock, are so frequent that they seem as routine as her unassuming comments after each race with history. But she acknowledged having the same nerves as any other competitor at the trials and, in all sincerity, said she didn’t take making the Tokyo Games for granted.

The five-time Olympic gold medalist owns world records in the 400-, 800-, and 1,500-meter freestyles. The usual gap for a world record is as thin as an Olympic medal. But Ledecky doesn’t just beat records, she transforms them. The 800? She has the 24 fastest swims of all time. The 1,500? The top 11 times. The 400? Twelve of the top 14 times.

Michael Phelps, the 28-time Olympic medalist, called Ledecky “the greatest female swimmer of our time.”

Coaches, teammates and competitors point to her powerful stroke, legendary training sessions, unusual blend of speed and endurance, and tenacity that is otherworldly. The traits, at least individually, aren’t uncommon in elite swimmers. And they’re ultimately suggestions straining to answer a larger question.

Ledecky leaves some of the most experienced people in swimming grasping for the secret to her dominance. Genetics? An iron will? Nature versus nurture? God? What transformed that girl who couldn’t make it across the pool?

After a year of uncertainty brought on by postponement of the Tokyo Olympics, top U.S. swimmers are ready for some familiarity at the U.S. swim trials.

Matt Barbini, USA Swimming’s national team performance director, recalled the feeling after Ledecky’s surprise victory in the 800 at the London Olympics in 2012 introduced the little-known teenager to the world.

“Oh, man, this is not exactly what we thought,” he said. “This is something really, really special.”

::

‘You’re going to get your head kicked in’

Before the London Olympics, Ledecky trained at the U.S. team’s camp in Knoxville, Tenn., with a small group of middle- and long-distance swimmers under legendary coach Jon Urbanchek.

What happened took everyone by surprise. The quiet 15-year-old usually kept up with the men, who noticed fearlessness and poise that belied her youth. She didn’t hesitate to start faster than they expected and maintain the aggressive pace. Sometimes she faded. Most of the time she didn’t.

“Some of the boys said, ‘Jon, get her out of our lanes. She’s swimming faster than we are,’” said Urbanchek, coach to 44 Olympians and an assistant on six Olympic teams.

David Marsh, an assistant on the team who served as the women’s coach in 2016, recalled coaches gathering when Ledecky swam.

“She’s swimming in full dude territory,” he said. “I don’t think she had a clue how fast she was going. She was just doing what Jon was saying.”

If any single item is responsible for her transformation, the grueling sessions away from television cameras and autograph-seeking fans might be it. She keeps logbooks chronicling most of her practices dating to 2011. There’s a decade’s worth of underwater video too. No detail is too small.

Ledecky sometimes texts her mother, Mary Gen, or brother, Michael, after a particularly good set. He describes them as “holy cannoli” swims that would leave almost anyone else’s jaw on the floor.

“I think she loves the training more than she loves competing,” Michael said.

While every distance swimmer grinds through thousands of monotonous yards each week, these sessions are somehow different for Ledecky.

“It can’t be easy to go train against Katie when you know you’re going to get your head kicked in,” said Keenan Robinson, Phelps’ longtime strength and conditioning coach. “But she shows gratitude and appreciation and keeps people coming back to get their heads kicked in.”

Barbini noticed the mix of intensity and care that’s as much a part of Ledecky as the blazing times.

“Katie wants to win by the most massive margin possible, but I don’t think she wants to break anyone’s soul like Michael Jordan did,” Barbini said. “It’s a remarkable combination, particularly for someone to be that dominant for so long, which takes so much commitment, while at the same time being so nice and polite and kind.”

The same all-out approach Ledecky brought to the final 25 meters of the 200 freestyle at the Rio de Janeiro Olympics — she edged Sweden’s Sarah Sjostrom by .35 seconds for gold despite feeling queasy — happens regularly in practice with nothing at stake other than numbers on a clock.

Andrew Gemmell, the coach’s son who competed at the London Olympics in the 1,500 freestyle, trained with Ledecky in the two years leading up to Rio. He good-naturedly described her competition-like intensity in practice as “really annoying.” Even years after the sessions, the words carry a mixture of awe and disbelief.

“There were days where I wanted to tap my dad and say, ‘Hey, can I just watch?’” Gemmell said. “I’m know I’m supposed to be doing this too. But can I please just watch? This is really impressive. I promise this isn’t because I’m getting my butt kicked.”

Gemmell warned other men in the training camp to be ready for Ledecky to beat them. Some said it would never happen. Then it did.

That continued when Ledecky arrived at Stanford as a freshman in 2016. Twice each week, she trained against long-distance swimmers Liam Egan and True Sweetser. Since NCAA rules keep men’s and women’s swim teams that don’t use the same coach from practicing together, Ledecky used lane 12 and Sweetser lane 11. They swam identical workouts.

“Katie wants to win by the most massive margin possible, but I don’t think she wants to break anyone’s soul like Michael Jordan did. It’s a remarkable combination, particularly for someone to be that dominant for so long, which takes so much commitment, while at the same time being so nice and polite and kind.”

— Matt Barbini, USA Swimming’s national team performance director

Some days she left him “absolutely demolished” and approached record paces in the middle of exhausting workouts.

“A lot of people have the tendency to want to protect themselves in their training,” Sweetser said. “Katie just dives in headfirst and really forces you to get the most out of practice. … She’s always trying to maximize her performance so there’s nothing left in the tank. It’s a mindset that different to go out as fast as you can without being blatantly reckless.”

She’s not afraid to fail. Sometimes that happens.

“If I have a bad practice, I don’t let it get to me,” Ledecky said. “I really haven’t had too many of those over the past couple months, so that’s a good thing.”

The words were matter-of-fact, delivered without a trace of pretense.

In the middle of a difficult practice, Sweetser noticed Ledecky staring at him. Her face was red. He thought the she was sizing him up as another opponent to defeat. Turned out a bigger foe lurked behind him: the pace clock.

::

Chocolate milk

The stroke that’s propelled Ledecky to record after record is connected to another legend.

Yuri Suguiyama, her first coach, watched Phelps break Australian Ian Thorpe’s world record in the 200 freestyle during the world championships in Melbourne. That performance burned into the coach’s memory. So did Phelps’ asymmetrical stroke that’s known as “galloping” or “loping” and is common among high-level men.

About 18 months before the London Olympics, Suguiyama suggested that Ledecky adopt the gallop. It worked.

“She was swimming like most classic female distance swimmers,” Suguiyama later told the American Swimming Coaches Assn. “It was two big kicks and bilateral breathing. But she was always bouncing up and down, really bouncy in the water and I think you can swim better than that.”

Ledecky uses a short left stroke, followed by a long right one, while breathing on her right side every other stroke, and repeating the pattern.

“She’s able to really lean into each arm,” Sweetser said. “That’s key to her success. Even elite women’s swimmers at the Olympics aren’t able to pull off that kind of stroke.”

A swimmer needs ample strength for this approach to work. Ledecky has plenty, starting with the hip turn and core that provide much of her power.

“She’s really activating her core and that allows her upper body to connect to her lower body and when you put those two together, it gives her really great timing and great catch,” said Elizabeth Nagle, an associate professor at the University of Pittsburgh who studies aquatic physiology. “That’s what’s allowing her to get such a good grab of the water … and have such good force generation per stroke.”

Experts single out the way Ledecky’s palm wraps about the water and pulls it back. They can’t quantify this, but believe she hangs onto more water than other swimmers.

“She feels water better than anyone else has ever felt water,” Barbini said. “You just watch the force that she pulls with and it’s way, way different.”

Laguna Beach’s Nyjah Huston brings a fierce commitment to training to a rebellious sport, making the skateboarder a star to watch in the Tokyo Olympics

Hideki Takagi, a professor at the University of Tsukuba in Japan focused on the hydrodynamics and biomechanics of swimming, underlined the importance of this trait.

“Even if they are fit and strong like a football player, they cannot swim fast if they do not have the skill to catch the water,” Takagi wrote in an email. “General swimmers tend to think that if they can just get their arms around faster and kick their legs faster, they can swim faster. However, elite swimmers focus on how to generate propulsion more efficiently.”

The collision of hand and water is one piece of a complex, fast-paced puzzle in which the grab and breathing and body rotation and head position and kick and proper body alignment and arms cutting into the pool at the precise angle must work in concert. For lengthy races like the 1,500 meters, this must remain constant for more than 15 minutes. Somehow she makes this look easy.

In a video posted on social media last summer, Ledecky placed a glass of chocolate milk on her head, then swam the length of the pool. Not a drop of milk spilled.

::

55.66

At the Olympic trials last month, Greg Meehan, Ledecky’s coach who leads the Stanford women’s swimming program and the women’s Olympic team, asked for a prediction. How fast would Torri Huske, the 18-year-old phenom headed to Stanford this fall, swim in the 100 butterfly final?

Ledecky said 55.66 seconds.

Huske won the race and set an American record in the event. The time: 55.66 seconds.

“I’m very proud of this,” Ledecky said.

It might be easy to brush off the prediction as a fluke, but chance doesn’t play much of a role when Ledecky is involved. She has an unnatural sense of what will happen in the pool — call it swimming intelligence — that’s as impressive to witness as it is difficult to quantify.

“Because of her analytical approach to training, she knows almost exactly how the race is going to go,” Sweetser said.

One key is obsessive attention to detail.

“She takes a little advantage by doing all these little things a little bit better and I think that all adds up to her being so much better than everybody else,” Barbini said.

But her career is also a two-way conversation. Each month, she sends practice video to Russell Mark, a former rocket scientist who is USA Swimming’s national team performance manager. They review the video together, as much for what he notices as her feedback.

That’s not new. When reminiscing about her pre-teen years in the pool, she told an athletic trainer that she cared more about perfecting her stroke than about winning. The process trumped everything.

“Some of these things that might have come naturally and unconsciously when she was 16, now it’s conscious,” Mark said. “She has recognition of these things in the middle of a race and can make an adjustment. … That shows a mastery. That’s amazing.”

::

‘Kind of a freak athlete’

When Bruce Gemmell took over as Ledecky’s coach at the Nation’s Capital Swim Club in late 2012, his young charge had an Olympic gold medal, but couldn’t do a pullup.

“What stood out to me was nothing stood out physically,” he said. “Is she tall for the average person? Yes. Is she tall for an elite swimmer? No. She wasn’t a great kicker. She wasn’t a great puller. She wasn’t great at skills or drills we would try and teach her. What I found over time what she was great at, though, was her desire to get better.

“There were many times where she was walking up for practice … and I think, ‘That’s the best female athlete in the world?’ I’d just kind of chuckle to myself because there’s nothing that said that.”

Other than standing 6 feet tall, a couple of inches above the average height for female swimming finalists at the Rio Games, she could blend into a crowd outside of the pool. She doesn’t have an unusually long torso or long arms or large hands. She doesn’t have Phelps’ attention-grabbing build that included an 80-inch wingspan and size-14 feet that seemed to double as flippers.

Allyson Felix is determined to make the U.S. Olympic track and field team for the upcoming Tokyo Games as she looks to add to her legacy in the sport.

Instead, Ledecky has a gift that defies measurement.

“She’s kind of a freak athlete,” said Lee Sommers, an athletic trainer in Bethesda, Md., who helped prepare Ledecky for Rio. “She doesn’t have a central governor like most athletes do, that mind-to-muscle idea that ‘I need to shut down right now.’ … There’s nothing you can throw at her that she can’t convince herself that she can do.”

Before Ledecky, Sommers had never trained a swimmer, so he approached her like other athletes reliant on overhead motion, focusing on core strength, shoulder stability, injury prevention, plus explosiveness in short distances. He can count on one hand the number of times she was floored by a workout. She’s also remained remarkably healthy, aside from occasional illnesses, in a sport in which unrelenting training exacts a toll on the body.

During a stint at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, Colo., in early 2016, Conor Dwyer, a two-time Olympian, engaged in a friendly contest with Ledecky jumping onto flat surfaces at increasing heights. Dwyer topped out at 40 inches. Ledecky, who could reach only 21 inches a few years earlier, reached a personal-best 39 inches. During their next training session, he recalled, she said, “We’ve got to get our 40.” She did.

“She’s kind of a freak athlete. She doesn’t have a central governor like most athletes do, that mind-to-muscle idea that ‘I need to shut down right now.’ … There’s nothing you can throw at her that she can’t convince herself that she can do.”

— Lee Sommers, an athletic trainer in Bethesda, Md., who helped prepare Ledecky for Rio

Then there’s the sheer efficiency of how her body works.

“I’m willing to bet she has a V02 max that’s better than anybody else on the face of the earth,” Robinson said, referring to the maximum amount of oxygen a person uses while exercising. “Her strength-to-body mass ratio is probably in the top 98%.”

All of this feeds Ledecky’s ability to do things in the pool that aren’t normal. On the fourth day of the Olympic trials, for example, she won the 200 freestyle by a full body length after pulling away in the final 50 meters. About an hour later, she returned to the pool for the 1,500 freestyle final. This is a completely different kind of race, 30 laps of endurance that is part of the women’s Olympic program in Tokyo for the first time. To no surprise, Ledecky, who first broke the world record in the event in 2013, recorded the world’s top time in the event this year on the way to another victory.

Competing in both events is rare enough. But within an hour of each other? Winning both? And not even appearing winded?

There are technical explanations: her aerobic system using oxygen with extraordinary efficiency, while her anaerobic system generates explosive bursts of energy. Or perhaps the answer is more basic.

“Are you willing to push yourself beyond all comprehension or are you not?” Nagle said. “She certainly is.”

::

She’d race in a cardboard box

A 58-foot-wide picture of Ledecky adorned the outside of the CHI Health Center in Omaha during the Olympic trials in 2016. A similar picture covered the front of the building as the trials took place last month, another reminder that she is the face of the sport.

Ledecky’s world records in the 800 freestyle and 1,500 freestyle are 1.95% faster than the second-best women. The world record margin for the 12 other individual events in the Olympic program is 0.44%.

The history-making has become so common, so many would-be competitors left so far behind, that expectations, just like the pictures, are larger than life.

“The standards for her externally, I think, are just tough sometimes,” Meehan said. “We don’t talk about it. But everybody feels that.”

Take the 400 freestyle final at the trials. Ledecky won easily in 4 minutes 1.27 seconds, the 43rd-fastest swim ever by a woman. But the time was almost five seconds off Ledecky’s world record set in Rio. And Ariarne Titmus, the 20-year-old sensation nicknamed “The Terminator,” posted the second-best time in history a day earlier at the Australian trials.

Ledecky, who has broken the 4-minute barrier in the distance 20 times, thought she had been faster. The time that would be a career-making moment for almost any other swimmer surprised her. But she addressed it and moved forward.

“The most important expectations are the ones that I have for myself,” said Ledecky, who graduated from Stanford with a psychology degree last month. “I think I do a pretty good job of sticking to those and not seeing what kinds of medal counts or times that people are throwing out about what I could accomplish if everything goes perfectly.”

That’s why Bruce Gemmell quips that Ledecky would be content to race in a cardboard box.

“She’s not doing it for the adulation, she’s not doing it for the title of the world’s greatest swimmer,” the coach said. “It’s just her commitment and desire for getting better.”

She has an uncanny ability to remain herself, not flinch in the face of scrutiny and focus on the task at hand.

“There’s a lot of noise,” said Janet Evans, the four-time Olympic gold medalist who is considered one of the greatest distance swimmers in history and now works as the chief athlete officer for the Los Angeles 2028 Olympic Committee. “There’s a lot more pressure when you’re 24 and going to the Olympics for your third Games as a heavy favorite versus being 15 and going to the Olympics with barely anyone knowing your name. The most impressive thing for me is blocking out the noise and not feeling the pressure.”

Urbanchek put it bluntly: “Nothing distracts her.”

“There’s no special sauce. Trust me. She’s not doing some special strength program that nobody else knows about. She’s doing what everybody else does. She’s just doing it better than everybody else.”

— Bruce Gemmell, Katie Ledecky’s coach at the Nation’s Capital Swim Club

Some of this immunity to pressure comes from her knack to set goals, internalize them, then turn them into reality. This started as a child. Mary Gen Ledecky, who swam in college, encouraged her daughter to write down goals. They were called “watch times.”

Years later, Gemmell read two items on Ledecky’s goal card: break the world record in the 800 freestyle by the following summer and swim 8:10 in the event in Rio. She set the record in the event nine months later in 8:13.36.

They realized the goals, lofty as they might seem for a teenager, were too pedestrian. The goals were adjusted to pursue times that felt a little scary, a little unreasonable, more than a little exciting: 3:56 in the 400 freestyle and 8:05 in the 800 freestyle. In keeping with Ledecky’s low-key personality, the goals stayed between them. She met both.

::

The mystery

The stories pile up. Ledecky breaking an arm in fourth grade, but jumping back into the pool with a cast. Or Mark finding Ledecky eating alone in the dining hall at the London Olympics the day of her 800 freestyle final, appearing as calm as a seasoned veteran. Or Gemmell calling other coaches for ideas on how to challenge this once-in-a-lifetime teenager doing “crazy stuff” in practice.

The questions pile up too. Is it her training? Her physiology? We don’t clamor for such answers while admiring a soprano’s voice or an actor’s ability to make us weep. We’re content to enjoy the gift. Sports, however, bring a desire for answers, for numbers, for specifics, especially for someone whose accomplishments almost have become disorienting. We want to know what transformed that girl who couldn’t make it across the pool?

But the more coaches and trainers and competitors grasp for answers, the more the reality comes into focus. Maybe the explanation is unknowable. Maybe there isn’t a secret. Maybe the history Ledecky is making is as remarkable as how she’s doing it.

“There’s no special sauce. Trust me,” Gemmell said. “She’s not doing some special strength program that nobody else knows about. She’s doing what everybody else does. She’s just doing it better than everybody else.”

And perhaps that’s the greatest mystery of all.

Coming Sunday: Home subscribers will receive the Los Angeles Times’ 24-page Olympic preview section, your guide to the upcoming Games. The section also will be available for purchase at latimes.com/store. Visit latimes.com/olympics now and throughout the Games for the latest Olympic news and analysis.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.