- Share via

Sunday night marks the launch of the HBO series “Winning Time,” which is based on Jeff Pearlman’s book “Showtime” about the eponymous Lakers’ dynasty of the 1980s. The foundation for one of the modern NBA’s most storied championship runs was laid in 1979, when Jack Kent Cooke sold the franchise to Dr. Jerry Buss. Before the Magic of the Showtime years, however, the Lakers needed a little luck.

Earvin Johnson wanted a hamburger.

He was a 19-year-old kid, fond of burgers and pizza and French Fries and any other cuisine guaranteed to block the arteries. Sure, he happened to be sitting in the presence of Lakers owner Jack Kent Cooke, perhaps the world’s least likely man to ever order a burger of any sort. But, hey, Johnson was hungry.

Scratch that. Starving.

It was a warm May afternoon in Los Angeles, and the most dynamic player to grace college basketball since Louisiana State’s Pete Maravich a decade earlier was in town to figure out whether he should return to Michigan State University for his junior season or jump to a professional sports league that had been crippled by poor TV ratings, player indifference and a dwindling fan base. On the one hand, in East Lansing, Michigan, Johnson — a local kid out of Everett High School — was a king. He had been nicknamed Magic as a fifteen-year-old high school freshman and now, having just led the Spartans to their first NCAA men’s basketball title, he could not walk the streets without being mobbed. “He really was beyond reproach,” said George Fox, his high school coach. “Earvin could do no wrong.”

Jeff Pearlman’s book on the Showtime era Lakers is the basis of a TV series on HBO, but the show “Winning Time” follows a different path from the book.

There was, however, the siren call of the NBA and specifically the siren call of Jack Kent Cooke’s thick wallet. On April 19, 1979, the Lakers and Chicago Bulls had engaged in a coin flip to determine which team would be gifted with the number one pick in the upcoming draft. Coming off of a 47–35 season, Los Angeles was in such a position because, three years earlier, the New Orleans Jazz committed one of the worst free-agent acquisitions in league history. The team signed thirty-three-year-old Gail Goodrich, a long-ago star on his last legs.

At the time, league rules mandated that the Jazz had to compensate Los Angeles with players, draft picks or money. After much haggling between the Lakers and Jazz general manager Barry Mendelson, New Orleans agreed to part with its first-round picks in 1977 and 1979, as well as a second-rounder in 1980. “Gail was great,” said Bill Bertka, the Jazz vice president of basketball operations. “But he was older, and he came to us and immediately tore his Achilles. That didn’t make us look so smart. Especially when we lost almost every stinkin’ game in 1978–79.” (The Jazz went a league-worst 26-56.)

When Larry O’Brien, the NBA’s commissioner, prepared to flip the coin inside the league’s New York City headquarters, the Bulls and Lakers felt their futures momentarily hovering in midair. Executives from both teams listened to the toss via speaker phone from their respective offices.

“Chicago, do you want to make the call?” O’Brien asked.

“We’d love to,” replied Rod Thorn, the Bulls’ general manager, who was sitting inside the team’s offices on the thirteenth floor of a Michigan Avenue building.

“Is that OK with you, Los Angeles?” O’Brien said.

“Fine,” said Chick Hearn, the announcer, who also worked as an assistant general manager with the team.

“We call heads,” said Thorn. A pause.

“OK, gentlemen, here we go,” boomed the deep voice of O’Brien. “The coin’s in the air.”

Behind HBO’s ‘Winning Time’: The real story of Magic Johnson, Jerry Buss and the 1980s Lakers, and how they changed the NBA and America.

Another pause. Another pause. Another pause.

“Tails it is!” O’Brien said.

Hearn let out a triumphant whoop.

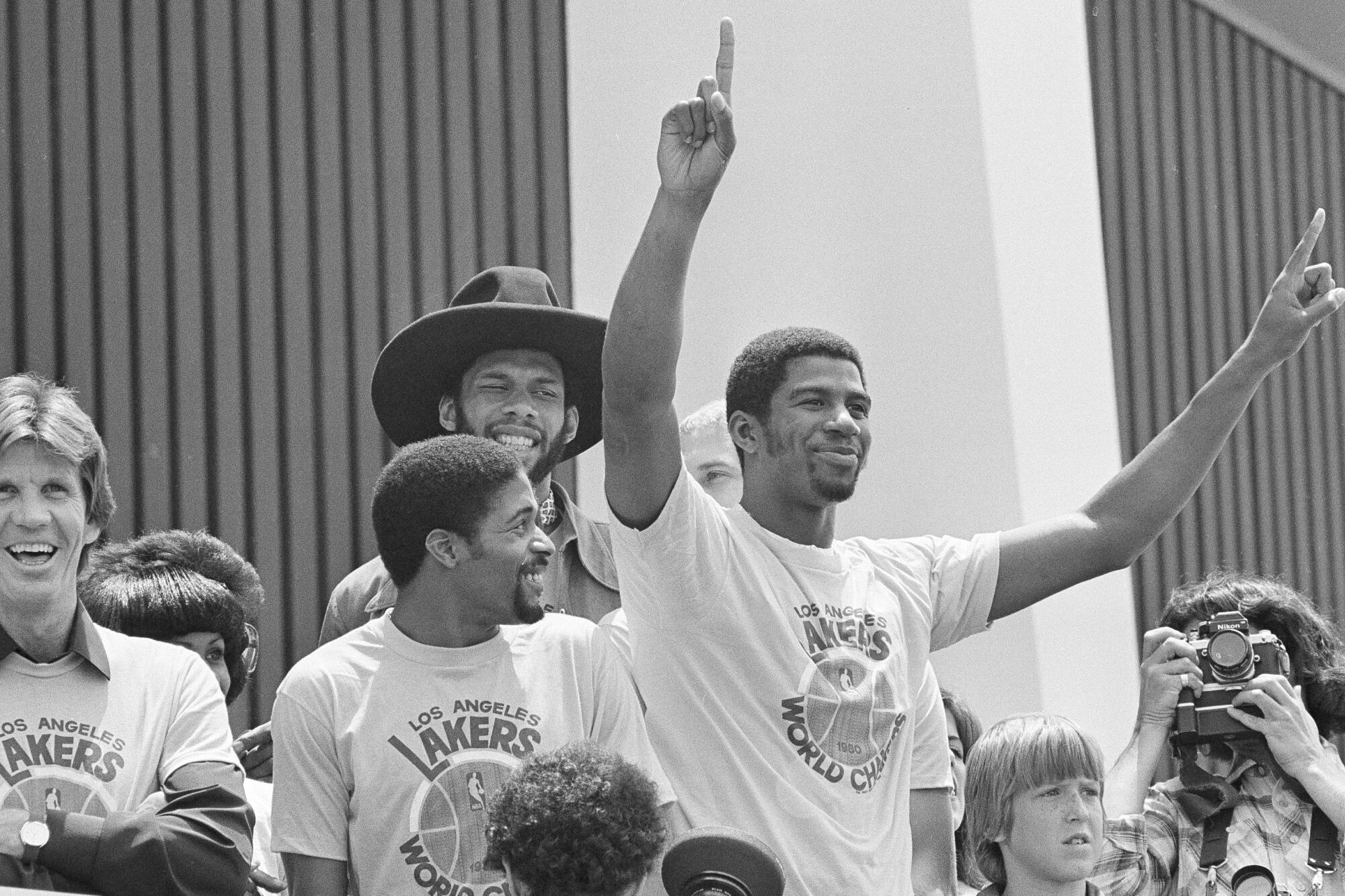

“I was playing basketball at Venice Beach,” said Pat O’Brien, at the time a reporter for KNXT-TV in Los Angeles. “The news came over a transistor radio, and people started screaming. ‘Yes! Yes! We’re getting Magic! We’re getting Magic!’ ”

Johnson was equally euphoric. The last place he wanted to go was Chicago, what with its awful winters (he was never one for the snow) and perennially dreadful basketball teams. The Bulls played in dumpy Chicago Stadium, and put forth an uninspired roster highlighted by the likes of Andre Wakefield and Wilbur Holland. Los Angeles, meanwhile, was but a dream to Johnson, who rightly envisioned a paradise of palm trees and 80-degree days and gorgeous women in wallet-size bikinis. Had the coin landed heads, Johnson would have returned to Michigan State for another season.

“There was a strong belief, for a brief time at least, that Moncrief, not Magic, would wind up a Laker.”

— Rich Levin, who covered the Lakers for the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner

So here now, a mere few weeks later, the kid was itching for a hamburger, befuddled by what was placed before him. Sitting at a table inside the Forum’s Trophy Room, Johnson was in town for lunch, sure, but really to feel out Cooke and the Lakers. The draft was still two months away, and both sides wanted to know whether a partnership could be reached.

Accompanying Cooke and Johnson were Hearn and Earvin Johnson Sr. Two of the player’s representatives, George Andrews and Dr. Charles Tucker, also attended. “Gentlemen,” Cooke bellowed, “I’m going to order lunch for you! We’re going to have some marvelous fish!”

Moments later, the plates arrived. The first thing Johnson noticed was the awful smell. He looked down and saw something bland and crusty.

Cooke observed Johnson’s bewildered expression. “They’re sand dabs!” he said. “Sand dabs!”

Johnson glanced at his father, leaned close and whispered, “I don’t know what a sand dab is.”

Cooke was nonplussed. “Young man, do you know how much a sand dab costs?”

Johnson shook his head.

“Well, they’re very expensive,” Cooke said. “It’s a very fine fish. Now eat.”

Johnson stabbed the listless sand dab with his fork. Nudged it around a bit. Pushed it left. Pushed it right. “I can’t eat this,” he said.

Cooke was outraged. “What are you talking about?” he said. “Do you know how much that fish costs?”

“If it’s OK with you, Mr. Cooke, I think I’d rather have a hamburger and some French fries,” Johnson said softly. “Would that be OK?”

This was not the way to make a good impression. Cooke was a formal man with formal tastes. If he wanted sand dabs, dammit, everyone was eating sand dabs. In this particular case, however, Hearn — one of the few men who had the owner’s ear — intervened. “The guy’s only nineteen,” he said. “The only thing he knows is hamburger and pizza.” A resigned Cooke sighed, then yelled toward the kitchen, “Can we have a hamburger?”

Nothing.

“A hamburger!” he screamed. “Get the man one!”

Within minutes, Earvin Johnson was gripping a burger. The accompanying smile was that of an eight-year-old securing a Happy Meal.

“You know,” Jerry West later said to Johnson, “nobody has ever done what you just did to Jack Kent Cooke.”

The podcast series will explore the history, culture, politics and people lighting up the small screen starting with the Showtime Lakers as a companion to the HBO drama premiering March 6

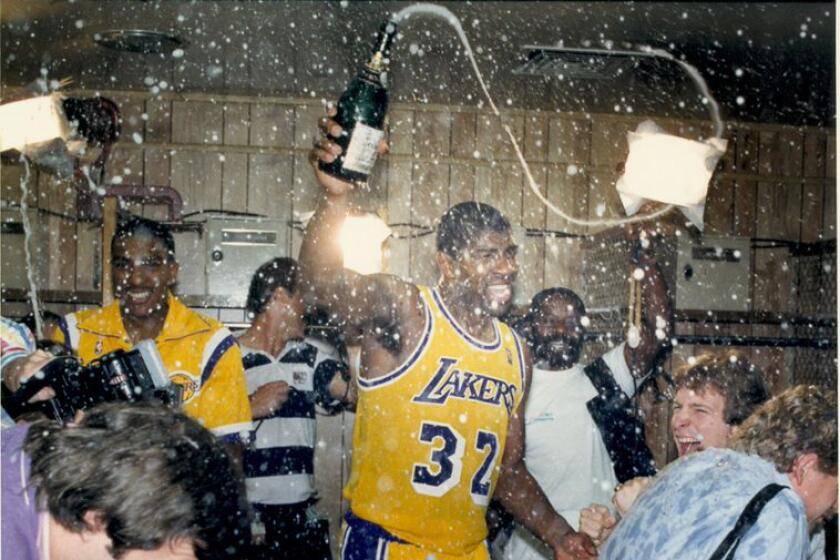

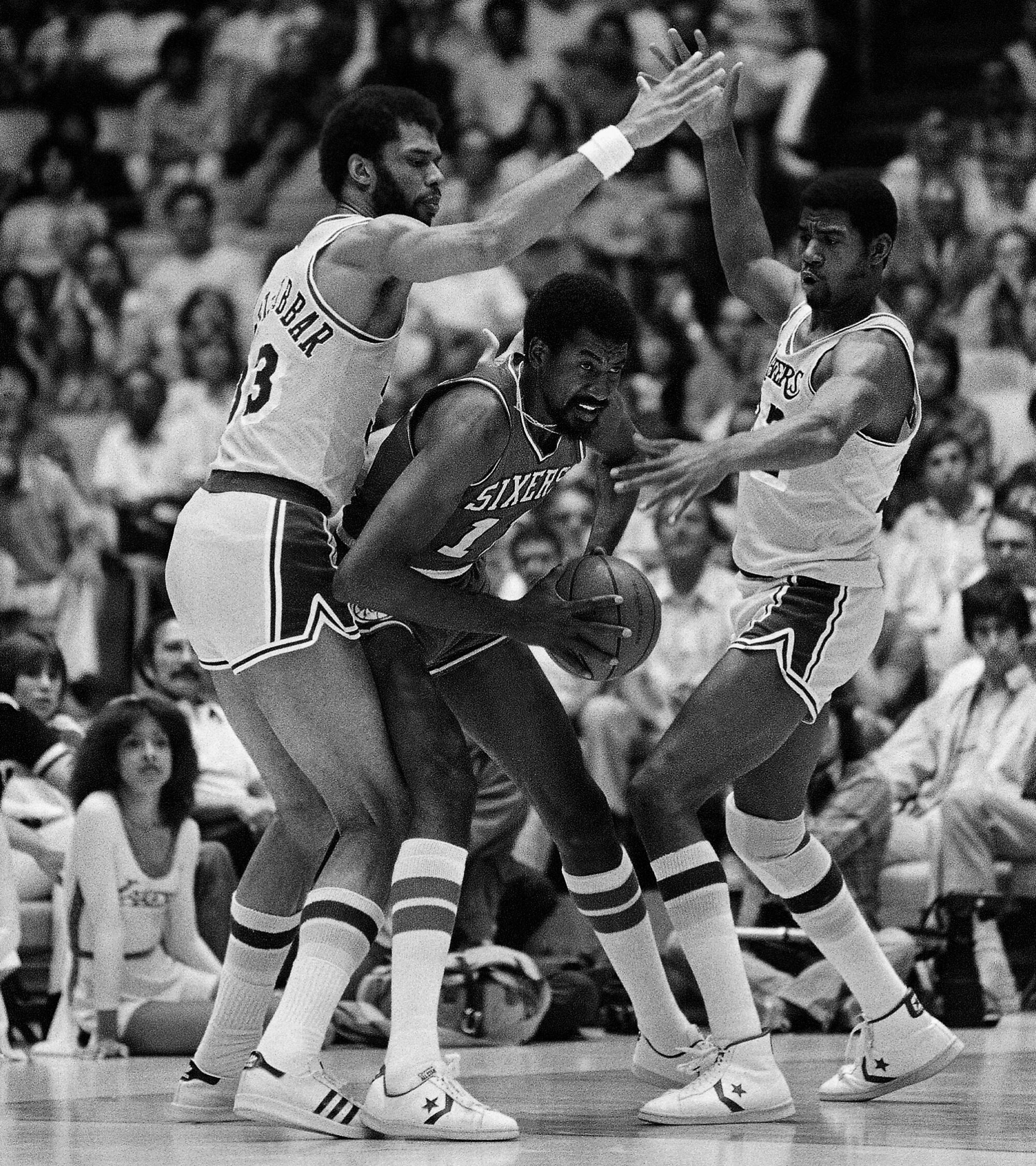

Beginning with that very moment, staring at a peppy teenager biting some meat, Hearn knew something about Johnson sparkled. As impressive as he was on tape, soaring past defenders, connecting on impossible no-look passes, spinning left, driving right, he was significantly more dazzling in person. At 6-foot-9 and 215 pounds, Johnson was a mountain of a man, the biggest, most powerful point guard anyone had ever seen. Yet it was his charisma, especially at his precocious age, that floored people. At the time, the face of the Lakers was Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, a moody soul who brooded a hundred times for every forced smile.

Johnson, on the other hand, was a ray of sunshine. He looked people in the eye, shook hands, talked about basketball as if he were describing a beautiful woman. Oh, and that smile — that blinding, all-glowing smile. “He was just a magnet,” said Claire Rothman, former manager of The Forum. “You wanted to be around him. You wanted to see him smile. You wanted to have lunch with him. Earvin Johnson was perfectly nicknamed. He had … it.”

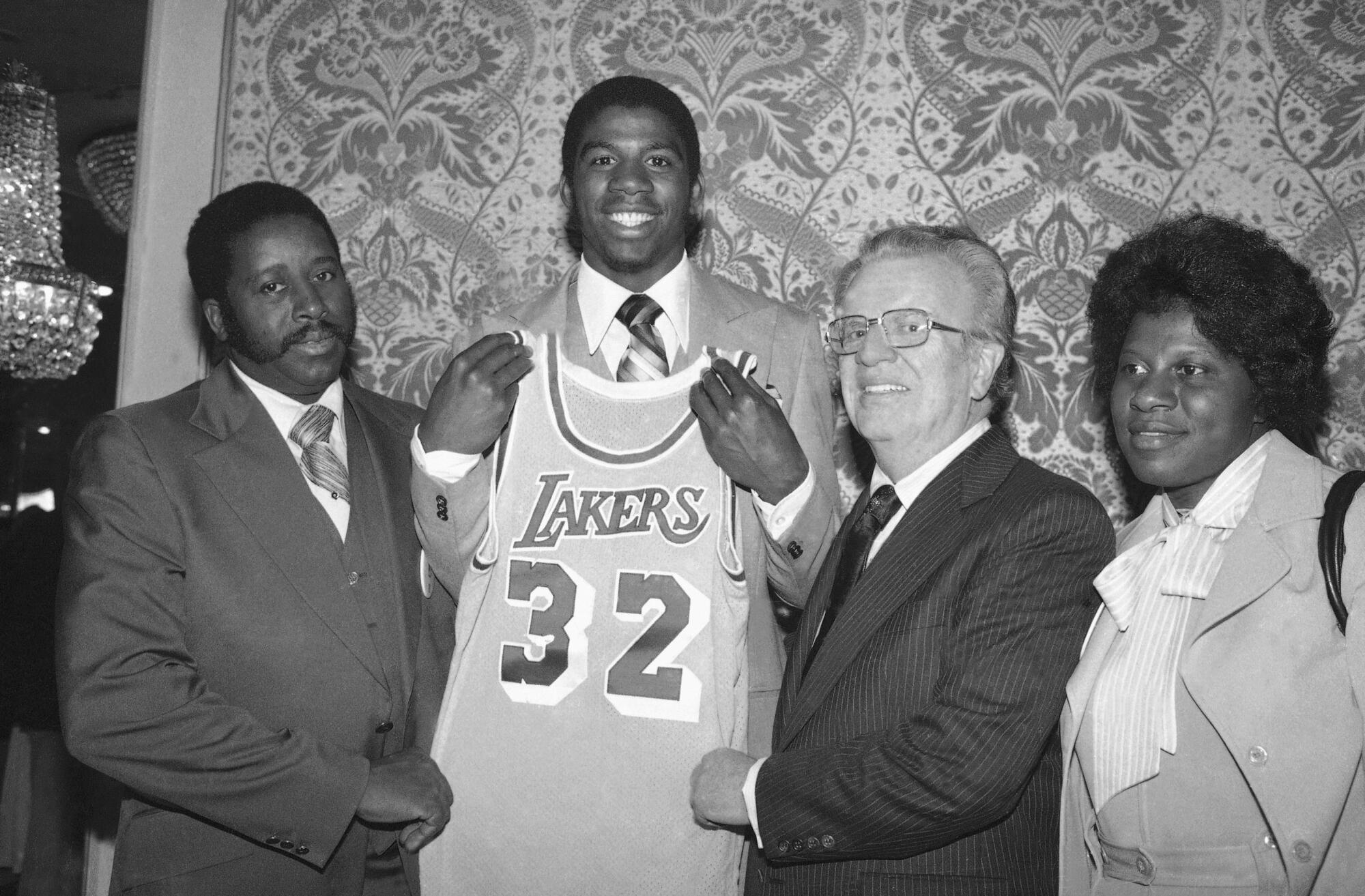

Cooke, however, wasn’t one to be swayed easily. Though he and Buss had already agreed in principle to the sale, Cooke insisted — without much argument from the soon-to-be owner — that the first pick in the 1979 draft be his call.

As he watched Johnson munch on his burger, Cooke asked what the kid was seeking as compensation. Aware that Abdul-Jabbar, arguably the NBA’s best player, was making $650,000 annually, Johnson confidently uttered, “Somewhere around $600,000 would be ideal — plus, I need an education allowance so I can finish at Michigan State.”

Cooke was not amused. “Let’s get one thing straight right off,” he said. “I’m not paying for your education. I put myself through school, and if I could do it, you certainly can. Now, we can offer you $400,000. It’s not what you’re asking for, but it’s a hell of a lot of money. And let me remind you that the Lakers have made the playoffs seventeen times in the last nineteen years. We’d love to have you, Earvin, and I hope you’ll play here. But the team has done just fine without you.”

The one thing Johnson didn’t know at the time (and wouldn’t know until more than two decades later) was that, in Cooke’s mind, he was merely another good college player in an ocean of good college players. Why, immediately after the draft, Cooke told those within his small circle of confidants that the team could have gone with Sidney Moncrief, the high-scoring guard from the University of Arkansas. That was the advice presented to him by Jerry West, the outgoing coach, who wasn’t fully convinced a 6-foot-9 point guard would function in the fast-paced NBA. Of all the ex-basketball players working for the Lakers, West was the one Cooke trusted most.

“Jack believed in star power. He deserves credit for that.”

— Former Former manager Claire Rothman on Jack Kent Cooke

“West wanted Moncrief, and he made it very clear to Jack Kent Cooke,” said Rich Levin, who covered the team for the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner. “There was a strong belief, for a brief time at least, that Moncrief, not Magic, would wind up a Laker.”

Even if he weren’t the smartest basketball man around, Cooke understood that sports were as much about salesmanship as on-court success. Despite winning 47 games and reaching the playoffs in 1978–79, the Lakers sold out only once, and averaged 11,771 fans in an arena that seated 17,505. The kid sitting before him was a 100,000-foot-high neon sign screaming see the Lakers! His roster, on the other hand, was composed of standout players who seemed either indifferent (point guard Norm Nixon), shy (forward Jamaal Wilkes) or downright offensive (Abdul-Jabbar). Cooke had waited a long time for Abdul-Jabbar to turn on the charm. He now seemed to realize it would never happen. “Jack believed in star power,” said Rothman. “He deserves credit for that.”

So, when Johnson met Cooke’s rebuff with an even stronger one — “I guess I’ll be going back to school” — the owner cracked. He invited Johnson and his entourage to stay the night in Los Angeles and return to the Trophy Room the following morning. On the drive to the hotel that evening, Earvin Sr. lit into his son. He was a man who’d spent years working multiple blue-collar jobs, struggling alongside his wife, Christine, a school cafeteria worker, to feed their ten children. Now his nineteen-year-old son was insulting sand dabs?

“I’ve worked in a factory my whole life for what he’s offering you for one year!” Earvin Sr. said. “And for something you love doing! Don’t be greedy, son.”

The next day, Cooke and Johnson negotiated back and forth until, finally, a deal was reached. The $500,000 contract made Johnson the highest-paid rookie in league history. With smiles all around, Cooke let his new superstar choose lunch.

“Pizza!” Johnson said. “Let’s order pizza.”

Cooke agreed, and before long, one of America’s richest men was munching on his first-ever slice of pepperoni. “This stuff,” he said, “is pretty good.”

From “SHOWTIME: Magic, Kareem, Riley, and the Los Angeles Lakers Dynasty of the 1980s,” published by Avery, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2014 by Jeff Pearlman. You can purchase the book here

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.