Column: How St. John Bosco and Mater Dei became superpower football programs

- Share via

Once upon a time, multiple schools in the Southern Section realistically could dream of winning a Division 1 football championship.

It was the days when public and private schools had equal chances. In the late 1970s, Fountain Valley, Loyola, South Hills, Los Altos and Edison won titles. In the 1980s, Riverside Poly, Fontana, Crespi, Servite and St. Paul claimed crowns. In the 1990s, Long Beach Poly, Bishop Amat, Mater Dei and Eisenhower became champions. In the early 21st century, Orange Lutheran, Santa Margarita, Corona Centennial and Poly ruled the Southland.

On Friday night at the Coliseum, St. John Bosco will play Mater Dei for the sixth time in the last seven seasons to determine the Division 1 champion. The days of drama, unpredictability and competitiveness are long gone. These two schools have separated themselves.

Yes, having competent coaching staffs helped. But equally important are CIF rule changes approved by member schools that created the opportunity for the two schools to leave everyone else far behind.

Let’s examine the timeline and the decisions that led to the making of two All-Star programs.

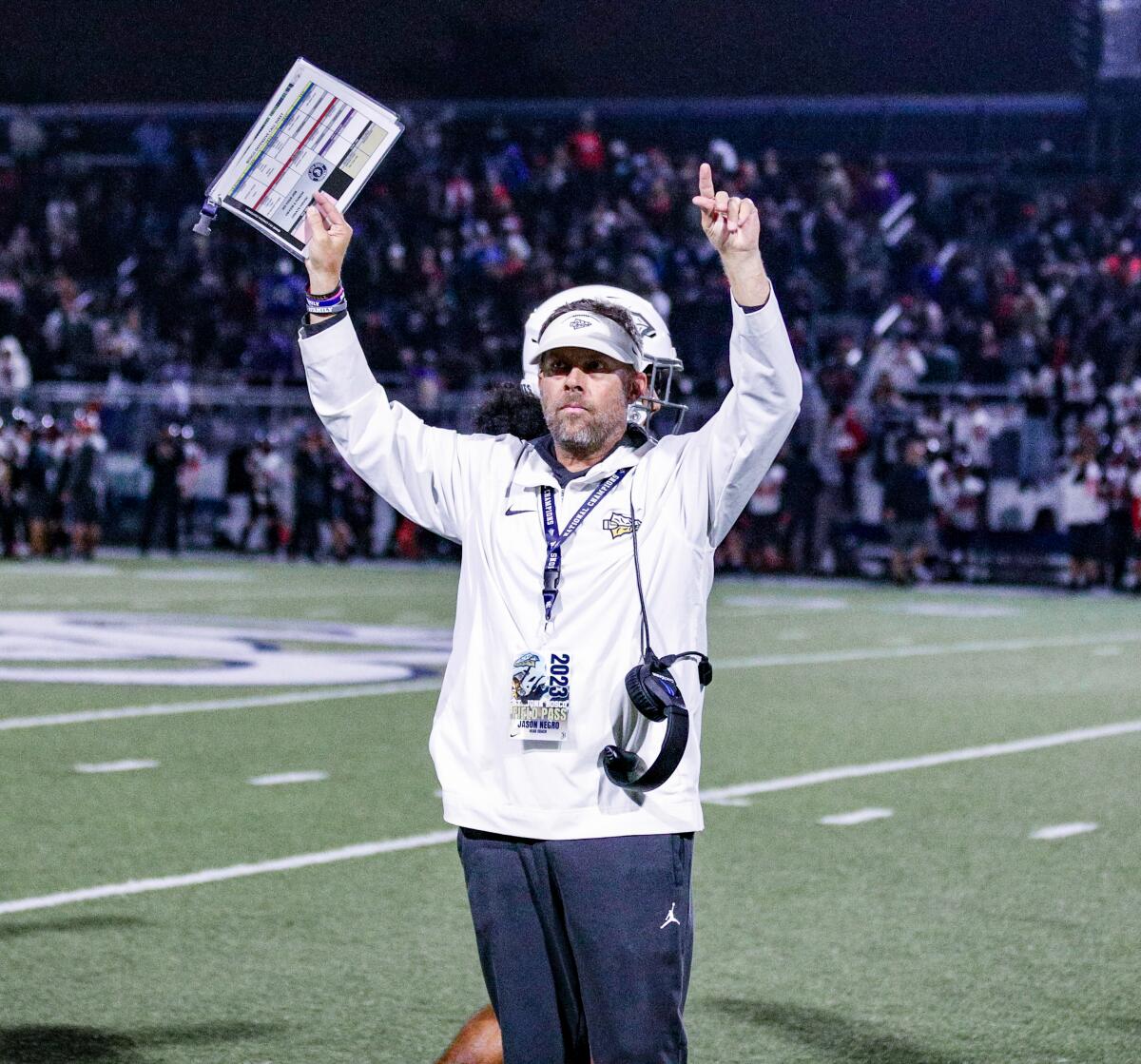

The hiring of Negro

In 2010, St. John Bosco fired Kiki Mendoza as football coach and brought in alumnus Jason Negro, who had been coaching at Trabuco Hills. A workaholic, Negro hired terrific assistant coaches (Chad Johnson among others), received financial support from his school and created buzz and college exposure for players. By 2013, the Braves were going 16-0 and would end up reaching the Division 1 final in nine out of the next 10 seasons. A new stadium was built, youth camps that had coaches working with middle school students gained in popularity, and top players were transferring in to fill key positions from graduating seniors.

Copying St. John Bosco

Former Mater Dei coach Bruce Rollinson won five titles in the 1990s. Then he went 17 consecutive years without winning another one. What changed is that Rollinson adopted Negro’s strategy of reaching youth players in middle school with camps and embraced transfers. Mater Dei expanded its attendance base to the Inland Empire with transportation vans for players. The Monarchs won titles in 2017, 2018 and 2021 and have reached the final every season since 2016, including this season under first-year coach Frank McManus.

Meanwhile, changes occurred across the sport that created the environment for little or no competition.

Year-round competition

In 2008, Southern Section schools voted to remove Rule 313 — known as the Association Rule. It eliminated out-of-season restrictions on the amount of time high school coaches could spend with their athletes during the school year. That cleared the way for year-round football practices and weight training beginning in January, passing tournaments in March and college-like weekly training sessions for those with available facilities and financial means.

Lawsuit changes everything

In 2010, a defensive end from Connecticut, Todd Hunt, transferred to Mater Dei. The Southern Section commissioner, Jim Staunton, ruled that Hunt had transferred for sports reasons and was therefore ineligible. Mater Dei went to court. By October, an appeals panel overturned Staunton’s decision. Mater Dei continued a legal battle, insisting the Southern Section was engaged in discrimination. The Southern Section spent more than $100,000 in legal fees before settling in 2012.

That same year, the 10 sections of the CIF approved a monumental change to transfer rules. Beginning in 2012-13, students who transferred without moving no longer had to sit out an entire season. A sit-out period was created lasting 30 to 35 days. Transfers began to rise statewide, reaching a high of 16,830 for 2017-18.

Sports transfers allowed

The final rule change in which members voted to raise the white flag of surrender on transfers came in April 2017. With the CIF’s legal bills on the rise, member schools approved a revision of wording that had banned athletically motivated transfers. The CIF insisted that honest parents admitting they moved for sports reasons were being punished while those who kept their mouths shut were being rewarded. Now sports transfers are allowed with no restrictions as long as they don’t follow a former coach.

After a major drop in transfers during the pandemic year of 2021-22 (14,818), the statewide transfer number for 2022-23 reached 15,931. It should easily pass 16,000 this school year and challenge the state record soon.

No rebuilding years

There are no more rebuilding years for St. John Bosco or Mater Dei because transfers step in at key positions and lower-level teams are stacked with talent from top youth programs. The only competition left for the Braves and Monarchs is for players from the IE Ducks and OC Buckeyes, premier youth teams.

Few challengers

Others haven’t given up hope. Sierra Canyon reached the semifinals in Division 1 for the first time aided by its own group of high-profile transfers. Sierra Canyon lost to Mater Dei 42-14. Centennial, which won titles in 2014 and 2015, continues to be the one public school consistently offering competition because of its enrollment (more than 3,000), prolific coach, Matt Logan, and track record of sending players to college and the pros (five current NFL players). Centennial lost to St. John Bosco in the semifinals 43-42.

If you’re upset about lack of competitive equity in Southern Section Division 1, member schools should look in the mirror. They helped create it with their rule changes.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.