How a Manhattan Beach free-care clinic became a prep football hotspot

- Share via

They come from Inglewood High. They come from Gardena Serra. They come from Redondo Union. They come from north, west and south — the Friday night brigade limping through the archway the next morning.

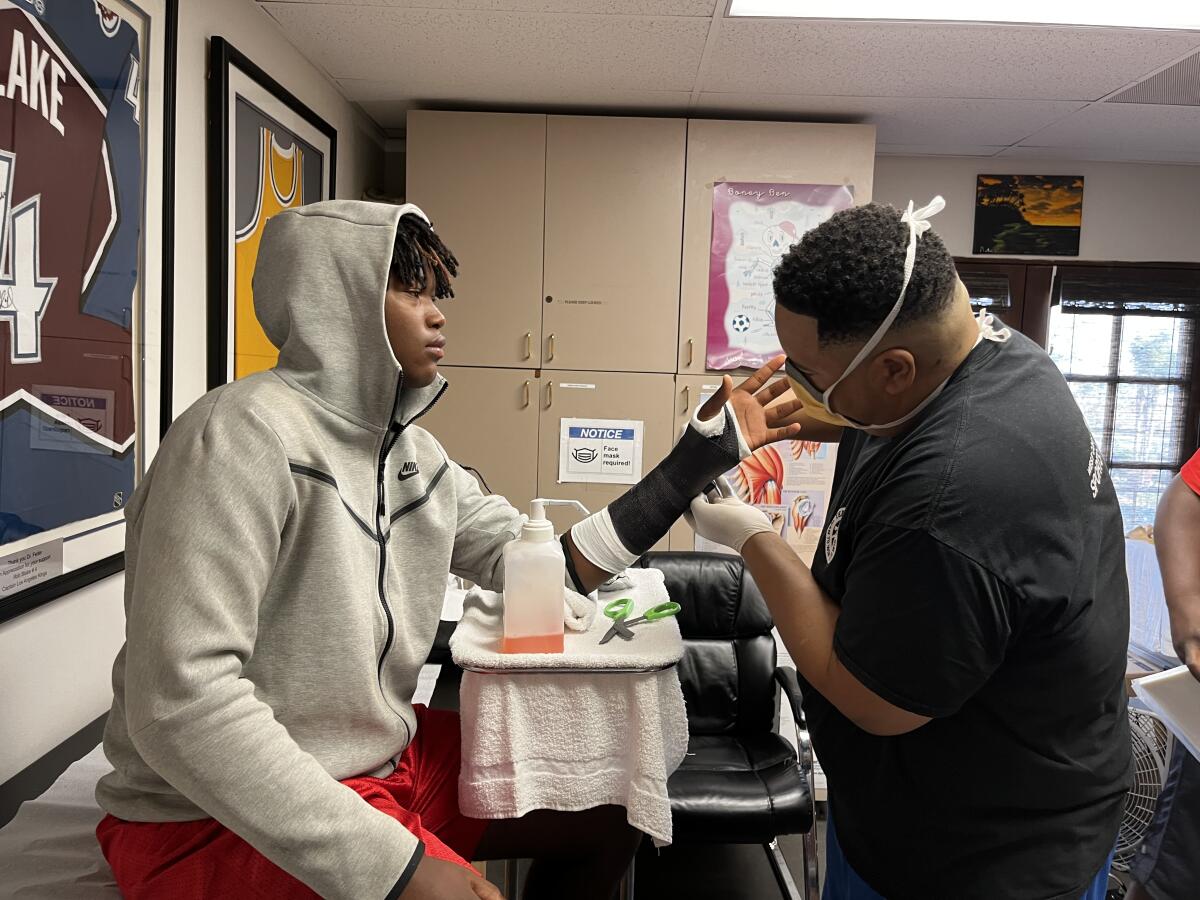

There’s a line of kids outside the West Coast Sports Medicine Foundation office in Manhattan Beach on Saturday mornings half an hour before the door’s open. The athletes squeeze like sardines into the waiting room as finely controlled chaos erupts in the hallway through the office door.

Names of patients and room numbers are scribbled onto a whiteboard as chatter swirls from office rooms. Physicians preach. He can’t bend his knee for two weeks. Trainees tither. Did anybody see this rib fracture on 4? Staffers shout. Make sure he goes to PT!

“Looks like, based on today’s volume,” foundation executive director Jill Sleight remarked Oct. 8, “there were quite a lot of injuries in high school football.”

The best-kept secret of Friday night football in Los Angeles: Saturday morning salvation, courtesy of the foundation. Every fall week for over more than 20 years, the group has hosted a free walk-in clinic on Saturdays run by Sleight and lead physician Keith Feder to provide medical treatment for high school athletes.

They treat all visitors. They aid all ailments. Rivalries disintegrate, grievances air, stars of the future divided no longer by lines of scrimmage but by training tables.

“Los Angeles, we produce some of the best athletes in the country out of our geography,” Sleight said. “The idea that the medical care is subpar for a lot of these kids … half the battle is just, ‘These kids need to have the same care.’ ”

So they embrace the craze. The Saturday morning whiteboard is almost always full.

In a game about a month ago, Compton Dominguez quarterback Aaron Cornett fractured his wrist while trying to brace his fall after a sack. Not the most devastating of injuries. But his father, Quentin, is a construction worker, on disability benefits.

“I hope they take the insurance we have,” Quentin worried.

Inside a patient room in the foundation office’s Saturday clinic Oct. 8, Cornett sat, left arm propped and primed as an aide gingerly wrapped his wrist in black gauze. Feder strolled in, said his pleasantries, evaluated for a moment and told Cornett he was good to play with a cast.

That was that. The cost of the cast? Nothing. The appointment? Zilch. The consultation? Nada.

“It’s awesome,” Cornett’s father said.

The clinic gives away about $800,000 to $1 million in free medical care each year, Feder estimated, and has seen upwards of 15,000 athletes.

“If there was other places they could go and get quality care in an efficient fashion, we wouldn’t have so many kids coming here,” Feder said. “But we’re happy to do it.”

After moving from New York to California and volunteering at a couple high schools, Feder discovered that unlike his former home — where the Public Schools Athletic League provided health insurance for prep athletes, he said — a large number of student-athletes he worked with didn’t have insurance. On top of that, Sleight added, many of the kids they still see don’t have certified athletic trainers on the sidelines at football games.

So the two drew up the foundation in 1994, later created a program called Team to Win, staffing athletic trainers on the sidelines of participating high schools. On Saturday mornings, those same trainers swing by the office to provide follow-up care on the injuries they treated the previous night.

“I think there’s a lot of relief from the parents and the kids to know that if something happens to them,” trainee Gabriel Nesbitt said, “they’re not going to fall by the wayside.”

The office has also become a pipeline for young athletes to pursue careers as physicians, thanks to a mentorship program run by Sleight at the foundation. The most recognizable graduate: Courtney Watson, head athletic trainer of the Los Angeles Sparks.

The clinic is locked in an ever-increasing struggle to fund its own outreach via the foundation. Yet Feder has refused to give up. In 2022, he won the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons’ Humanitarian Award.

“This thing doesn’t exist without Dr. Feder’s passion and commitment,” said Mitch Huberman, a foundation board member.

It’s an ever-widening cycle, the foundation’s network slowly spreading. They’re officially partnered with 17 high schools. When others find out. They flock in droves. Sometimes Sleight has to type a patient’s name into Google just to figure out what school they’re from.

The bustle in the back hallway doesn’t slow until the afternoon.

“We joke, ‘You cannot get married during football season,’ ” Sleight said of her trainers.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.