Puig, Kershaw tutor Cuban children during clinic

- Share via

Reporting from Havana — Kids and baseball. They’re two things that generally transcend language.

So when Clayton Kershaw found himself standing on the mound at Havana’s famed Estadio Latinoamericano on Wednesday, his lack of Spanish did little to hinder his ability to communicate with the nearly 200 grade-school players who showed up for a midday baseball clinic.

Kershaw spent two hours under a punishing sun playing catch, tinkering with windups and generally encouraging kids who couldn’t understand a word he said, but understood the messages clearly just the same.

The clinic was part of Major League Baseball’s three-day goodwill trip, the first step toward what both MLB and the Cubans are hoping will be improved relations between the federations running the sport in the U.S. and on the island.

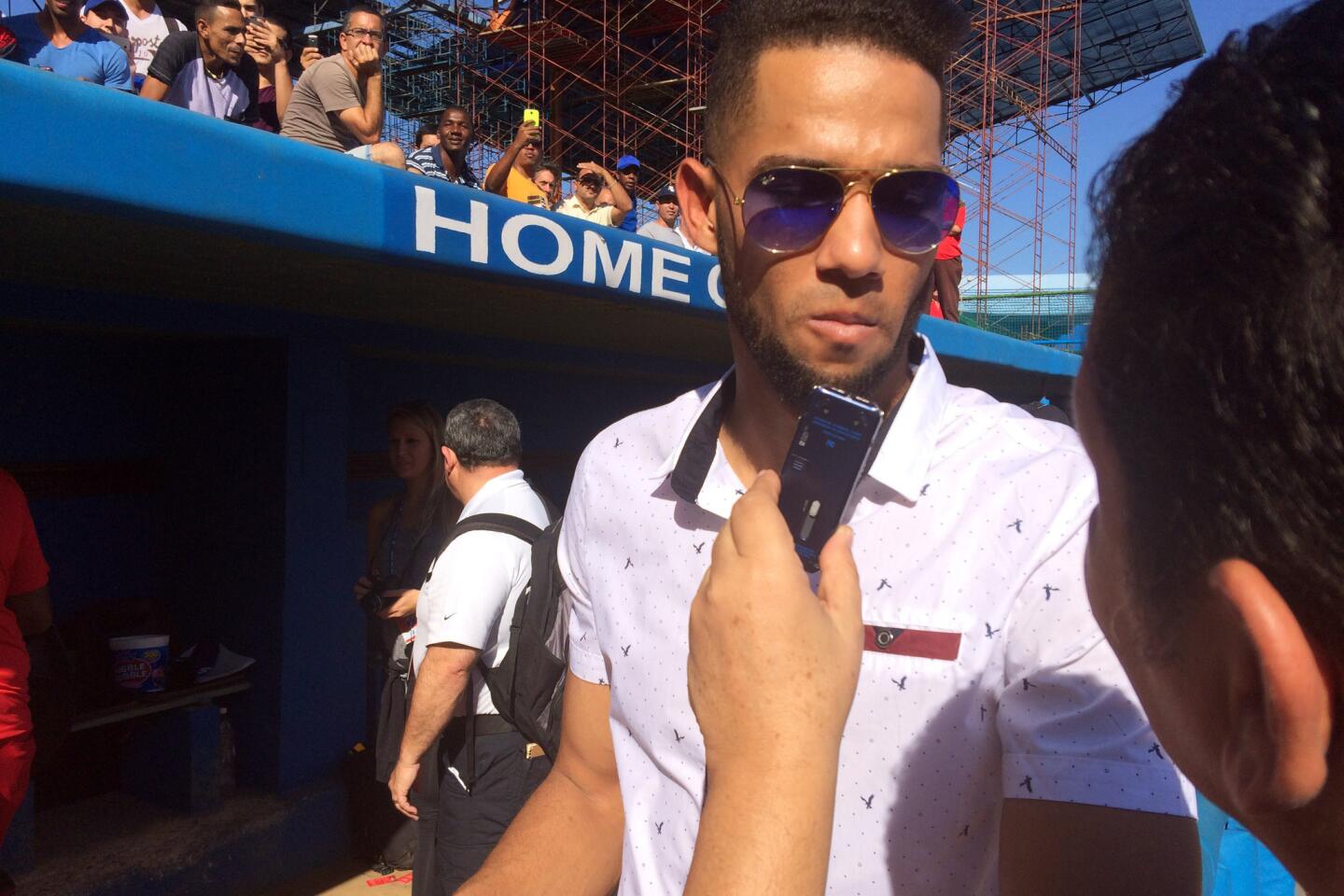

While Kershaw worked with the pitchers, Dodgers teammate Yasiel Puig, a Cuban defector, stood surrounded by a crowd of children in right field. Two other defectors – catcher Brayan Pena of the St. Louis Cardinals and free-agent shortstop Alexei Ramirez – also shared the secrets of their positions as groups of children rotated from one drill to the next.

“Education, education, education,” Pena, who left Cuba as a teenager, shouted in Spanish as he stood in front of the plate. “If you want to be a catcher you have to be smart. So stay in school. Learn.”

It was a strange tableaux: The defectors, once considered traitors on the island, wearing the jerseys of the big league clubs that made them millionaires while offering inspiration to the great-grandchildren of Cuba’s socialist revolution. Also milling about on the field were former national team stars Omar Ajete, Orestes Kindelan and Pedro Luis Lazo, who declined to leave the island for the majors and its riches.

In the third base dugout, Antonio Castro, son of former Cuban president Fidel Castro, talked with former Dodgers manager Joe Torre. And below the scoreboard, Cuban and American flags hung side-by-side from the top of the center-field wall.

But this was about baseball, not politics, and for anyone who bothered looking, there was a clarity in the seeming contradiction. And like Kershaw’s teaching, you didn’t need to share a language to understand the message.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.