Even after mild cases of COVID, long COVID symptoms can linger for a year or more

- Share via

For some COVID-19 patients, the initial illness isn’t nearly as bad as the persistent and sometimes disabling symptoms that linger for months or years afterward. These are the people with long COVID, a complex chronic illness that can afflict without regard for age, sex, vaccination status or medical history.

A study of nearly 2 million patients in Israel offers new insights into the trajectory of long COVID, particularly for younger, healthier people whose COVID-19 cases were mild. Researchers found that although most protracted symptoms subsided within a year, some of the syndrome’s most debilitating consequences — namely dizziness, loss of taste and smell, and problems with concentration and memory — still plague a minority of sufferers a full year after the initial infection.

For the study, published Wednesday in the medical journal BMJ, researchers examined the health records of more than 1.9 million members of Maccabi Healthcare Services, one of Israel’s largest health maintenance organizations. Among them were just under 300,000 people who tested positive for the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus between March 1, 2020, and Oct. 1, 2021, and who were not hospitalized in the first month after infection, a sign that their cases were mild.

The researchers matched each coronavirus-positive subject with an uninfected person in the sample who had the same age, sex and vaccination status and a similar history of risk factors such as diabetes, cancer and obesity, among other preexisting conditions. Then the investigators tracked the medical records of both members of each pair to see the health issues they experienced over the next 12 months.

“When we started this study, there was a lot of uncertainty regarding the long-term effects of the pandemic,” said computational scientist Maytal Bivas-Benita, who conducted the study with colleagues at Israel’s KI Research Institute.

Most COVID-related symptoms declined sharply in the first months after infection, including breathing difficulties, chest pain, cough, joint pain and hair loss, a side effect that often accompanies acute physical stress.

The older a patient was at the time of infection, the more likely they were to report long COVID issues. And many long COVID sufferers still grappled with their symptoms a year after becoming sick.

A new study offers insight into the prevalence of long COVID and suggests who might be more likely to develop the condition.

For instance, six months after a mild bout of COVID-19, unvaccinated people were 5½ times more likely to report problems with smell and taste than their uninfected peers. Even at the 12-month mark, the former COVID-19 patients were more than twice as likely to have trouble with these senses.

Likewise, former COVID-19 patients continued to have elevated risks of shortness of breath, weakness, and problems with memory and concentration a year after they first became infected.

Other long COVID symptoms tended to resolve themselves more quickly, the study authors found. Within four months, those who were once infected were no more likely to struggle with coughing than those who remained infection-free. Complaints of heart palpitations and chest pain were equally likely in both groups after eight months, and the same was true for hair loss after seven months.

The authors concluded that mild COVID-19 cases do not lead to serious or chronic long-term illness for the vast majority of patients and that they add “a small continuous burden” to the healthcare system overall.

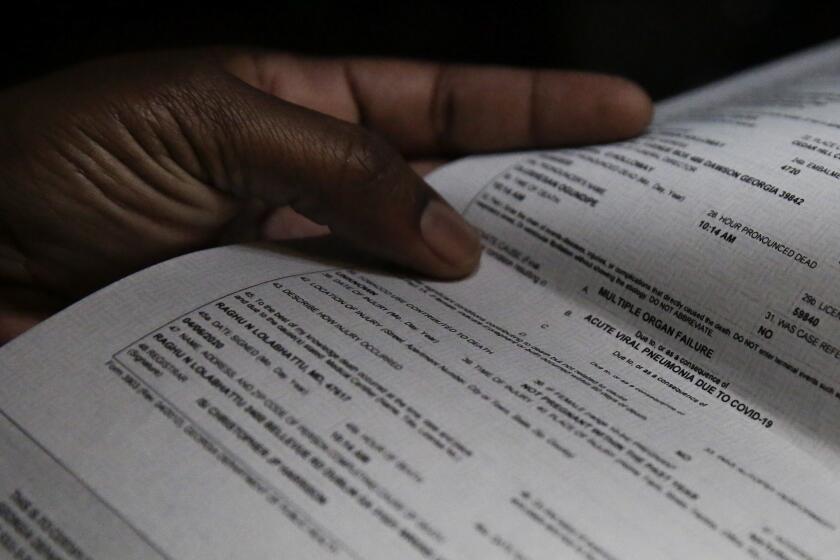

Long COVID illnesses contributed to about 3,500 deaths in the U.S. through the end of June 2022, according to a new report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Advocates for long COVID patients say that big-picture view glosses over the struggles of patients who are disabled by their lingering symptoms.

“Things like cardiac arrhythmias, problems with memory, concentration — all these types of symptoms not only are problematic medically, but also impede a person’s ability to work and live their daily life,” said Melissa Pinto, an associate professor of nursing at UC Irvine who studies long COVID. “Not all symptoms are equally problematic.”

The Israeli researchers noted that many long COVID symptoms worsened during the first six months of the illness before beginning any kind of decline, an observation that tracks with the experience of many long-haul patients.

“There are some concerning findings, including that some major neurological and cognitive symptoms do not decrease over time,” such as memory and concentration loss, said Hannah Davis, a co-founder of the Patient-Led Research Collaborative, a research group that focuses on the condition.

She added that the new study is in line with previous work showing that neurological symptoms worsen over the first four months of illness.

“This kind of finding is vital to communicate to the public for two reasons: first, to let new long COVID patients understand what to expect, and second, to give future researchers a clue into the possible mechanism,” Davis said.

A study of more than 1,200 COVID survivors who were once hospitalized finds that about half have at least one symptom a year later.

The researchers relied on diagnostic codes to see which symptoms affected patients. That approach excluded more recently defined ailments like postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, or POTS, which received a code in the U.S. only in October.

POTS is a disorder of the autonomic nervous system that affects blood circulation. It can be triggered by infections, and somewhere between 2% to 14% of COVID-19 survivors have been diagnosed with POTS. The condition’s symptoms include many of the persistent ones reported in the Israeli study: heart palpitations, dizziness, weakness and problems with concentration.

“It’s great that they are trying to collect this kind of data. But there are inherent flaws in electronic health records-based research that would cause me to question [whether] the results actually capture the lived experiences of these patients,” said Lauren Stiles, an executive committee member of the Long COVID Alliance and president of Dysautonomia International, an advocacy group for patients with autonomic nervous system disorders.

“What we’re seeing in the long COVID patient community is that a good subset of people are seeing some improvement over the first year,” Stiles said. “But there is a substantial number of patients who have a very long-lasting chronic illness, who are now going on three years of unrelenting illness.”