Bones, sweat and years: What it takes to dig up a dinosaur

- Share via

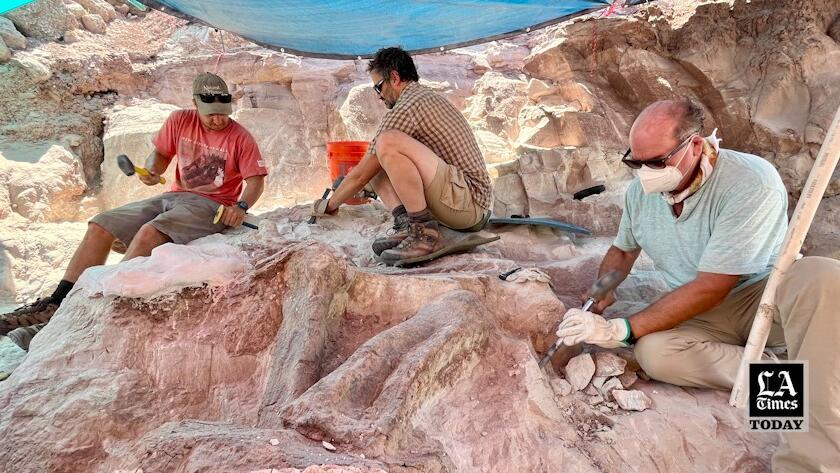

BITTER CREEK, Utah — A dental scaler, that hook-ended metal tool a dentist uses to chip away plaque, makes the exact same sound against a stegosaurus femur that it does on a human tooth.

You can’t always hear it. A fossil quarry is deafeningly loud when the jackhammers and rotary hammers are going. The relentless clank-clank of hand chisels knocking away ancient sandstone can ring in your ears long after you’ve set down the hammer and hiked back to camp.

But the closer the bones get to the surface, the quieter a quarry gets. The dinosaur’s remains are more vulnerable during excavation than at any point since the animal died 150 million years ago. Get sloppy with the chisel and a few priceless eons of natural history could crumble under your work gloves.

Nature takes at least 10,000 years to make a fossil. There’s no need to rush it now.

“I take my time,” said paleontologist Luis Chiappe, gently brushing ancient dust from a tibia with a hardware store paintbrush. “Like the way I like to sip a good wine.”

Chiappe is director of the Dinosaur Institute at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, where these bones are bound.

The museum already has a skeleton of a plate-backed, spiky-tailed stegosaurus. It’s mounted in the Dinosaur Hall alongside the bones of an allosaurus, a contemporary predator. The fossil emerging from the sandstone of southern Utah may never go on display. But it’s just as valuable to the institution.

The Natural History Museum is both a showcase for scientific discovery and a laboratory for it. Like the majority of the museum’s fossils, the remains of this stegosaurus will be brought into the collection as research specimens, to be studied by paleontologists in California and around the world.

Every fossil, from a fearsome skull to the nubbliest little metatarsal, is an irreplaceable data point in science’s constantly evolving understanding of the roughly 165 million years dinosaurs spent on this planet. The museum has drawers and shelves full of these relics, each carefully labeled and cataloged, awaiting researchers seeking to understand Earth as it was.

And that’s why, in the middle of July, a team of paleontologists, preparators and students piled into trucks in Los Angeles and set out for scorching southern Utah. To build a worthwhile museum collection, someone has to go out and collect it.

The quarry is lodged on the side of a hill overlooking a broad wash on the Colorado Plateau. Sandstone cliffs rise in the distance. To the south, the green banks of the Colorado River stand out against the scrubby badlands.

In the late Jurassic era roughly 156 to 144 million years ago, this area was a flat plain etched with rivers. Grass hadn’t arrived on the planet yet. Neither had flowers. Even the first Tyrannosaurus rex wouldn’t appear for an additional 80 million years.

That’s the world this stegosaurus knew. As soon as it died — it’s impossible to know how — its body was covered in mud and silt before opportunistic scavengers could scatter it.

Time passed. A lot of time. Skin and the keratin covering the plates decomposed. Water from the surrounding mud seeped into the bones, where mineral deposits slowly replaced organic material.

About 85 million years after this stegosaurus fossilized, the last dinosaurs went extinct. An additional 65 million years passed and humans arrived on the planet.

Fossilization demands such specific conditions that, at best estimate, less than 0.1% of all living things end up preserved this way. An even smaller number are found.

In the early 1990s, amateur fossil hunters noticed an odd protrusion in the Utah rock. Their report made its way to the Bureau of Land Management, which manages the land and any fossils found on it on behalf of the federal government.

The bureau was tasked with finding a suitable scientific outfit to collect the fossils before nature disposed of them. Once a rock wears away enough to expose a fossil, the specimen starts to erode with it. Countless fossilized dinosaurs disappeared this way before humans decided to collect and study them.

The remote and somewhat awkward hillside location made for a challenging excavation, and a few museums passed, said ReBecca Hunt-Foster, a National Park Service paleontologist who was then the district paleontologist for the BLM. She called Chiappe, who was interested.

After a years-long review to determine that their proposed excavation wouldn’t harm plants, cultural sites, animals, air quality or the surrounding landscape, the museum secured the permit.

Continents have shifted since the dinosaur age. In the stegosaurus’ lifetime, what are now the central Western states were only about 600 miles from modern-day Portugal.

That’s where Fernando Escaso, a paleontologist with Spain’s National University of Distance Education, found his first stegosaurus.

Escaso started college as a biology major but switched to paleontology, because he wouldn’t have to kill any animals for the sake of research.

In 2000 he was part of the team that discovered the first stegosaur fossils outside North America. It was a memorable find, and a picturesque one: the fossils, black bones against pale gray stone, were on a cliff overlooking the sea off Portugal.

There would be no ocean views on this dig. The site is a bone-jarring 40 minutes on a rocky dirt road south of Interstate 70. It has no running water or electricity. There’s a lot of work before the digging starts: pitching tents, smoothing a trail from camp to quarry, setting up the tables, coolers and propane grill that serve as a field kitchen. The bathroom is a plastic bucket in an outdoor shower tent.

The temperature hit triple digits most days. Drinking water turned bathtub-hot in the jugs. Forget a tool outside the sunshade and in a few minutes it was too hot to touch with bare hands.

A small canopy of tarps and PVC pipe erected over the quarry protected the team and their fragile specimens from the baking sun. Outside the tarp, an upright shovel thrust into the dirt flew a California flag with the grizzly swapped for duck-billed Augustynolophus morrisi, the state dinosaur. (California spent most of the dinosaur era underwater. The pickings are slim.)

Beneath the relative shade of the tarps, Escaso knelt in the dirt and ran his finger along the fossils exposed so far, identifying each bone. Femur. Tibia and fibula. A vertebra, the tip of what might be a pelvis, and the key tell: the broad, ridged remnant of one of the bony plates that ran down the dinosaur’s back.

There could be more bones beneath. There’s no way to know without painstakingly scraping away the rock.

“This is like a game,” Escaso said. “The process of fossilization is very, very rare and very complicated.” It’s not unusual, he said, “to have a lot of hope to find a complete skeleton and just find two bones.”

“Complete” has a different meaning in paleontology. The most complete stegosaurus skeleton has only 85% of its bones accounted for.

Stegosaurs lived on this planet for at least 2 million years. Remains of only several dozen individuals have been found. Only about 30 museums around the world, including the Natural History Museum, have enough stegosaurus bones in their collection to display in skeleton form.

Even that is actually a lot of evidence for a dinosaur species. Many species have been identified from just one partial skeleton, or even a single bone.

That’s why all these discoveries matter, Escaso said. Every bone is a piece of a puzzle nature jumbled up eons ago.

“The research starts here,” he said, pointing to the fossils. “The first part of the laboratory is this. The most important part, I think. Because if you don’t have this, you don’t do the other studies. You need to have bones in order to do the other things.”

Labs like those at the L.A. museum are where many of paleontology’s most exciting discoveries happen. Thanks to new technology, scientists have identified about 45 new dinosaur species every year, on average, since 2003.

Previous generations of scholars had to break a fossil apart to peek inside. Today a CT scanner can peer inside a dinosaur’s skull to reveal the cavities that once held its brain and sensory organs. Paleontologists can endlessly rearrange digitized bones, applying pressure to virtual legs and jaws in ways that would be impossible with delicate specimens.

With today’s tools, “we can really bring these animals back to life,” said Paul Byrne, a USC doctoral candidate and the Dino Institute’s graduate student in residence, as he readied a set of chisels. “It’s a contrast, because the digging part is very much the same as it has been for 150 years.”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

A 19th century dino hunter would recognize most of the team’s tools. So would a Home Depot shopper. Most are manual and analog: paintbrushes to sweep away dust, dental scrapers and air scribes to pry debris from delicate crevices, chisels and hammers to remove surrounding rock.

Early in the 24-day expedition, the team lugged a 400-pound generator up a half-mile trail to charge the power tools. Jackhammers and rotary hammers blast away layers of rock that formed over the dinosaur’s gravesite.

Once in the bone layer, fossils could be anywhere, in any order. Real dinosaur fossils look less like that T. rex skeleton in Disneyland’s Big Thunder Mountain and more like a dinosaur skeleton building set a child has torn to pieces and scattered.

Distinguishing fossil from rock can be tricky. Texture matters. Sandstone leaves ghostly dust on a fingertip swiped across its surface no matter how much it’s brushed.

Bone is different. Clean away eons of dust and what emerges is something smoother, more luminous. The light hits differently.

“A bone is a bone, but every spot is different,” said Beau Campbell, a senior preparator at the Dinosaur Institute. (Back in the lab, preparators clean and repair fossils for study.) Every quarry has its own code, tiny details of color, grain and texture that distinguish fossil from rock. “It’s an acquired skill,” Campbell said, but “once it clicks and you get it, everything opens up.”

The team agrees that Escaso has a knack for this. Bone is more porous than rock, he said, kneeling and placing a dusty hand along the remains of a tibia. The texture is different.

After a while, he gave up trying to explain.

“You can see the difference. It’s easy to see the difference,” he said, gesturing toward a knob of ancient bone that looked, to an untrained pair of eyes, exactly like the surrounding rock.

Chiappe perched on a small ledge alongside the dinosaur’s lower leg, expertly dispatching fist-sized chunks of rock with a chisel. He noticed Escaso peering closer at the bones.

“Qué tienes?” Chiappe asked. What do you have?

“Una otra vértebra,” Escaso replied. Another vertebra.

Chiappe scooted down next to him. Both men leaned in to examine the fossil, noses inches from the bones.

“This is the tip of the femur,” Escaso said, pointing to a knob in the rock. “And this is the vertebra,” he continued, lightly tapping a slight bulge above it — the first sign of a new bone.

It’s a small thing. But, its practitioners say, it’s what makes this work so enticing. By the end of the dig, the team would discover another plate, a tail spike and multiple tail bones. There may be more fossils buried in the rock. Those will have to wait for next summer.

“It can be very addictive, seeing what you’re going to find,” said Erika Durazo, a senior preparator. “That’s always exciting — being the first eyes to uncover things.”

Durazo was sitting in a camping chair at the end of a long day, waiting with the rest of the team for their tents to cool enough to be tolerable for sleeping. Overhead the sky was brilliant with stars.

Some were 150 million light-years away, Chiappe reminded the group. Their light began the journey to Earth when the stegosaurus was still alive, stomping around in a different world.