With old-school technology, can Novavax win over COVID vaccine skeptics?

- Share via

Since their debut just 18 months ago, three COVID-19 vaccines have saved an estimated 2.2 million American lives, changed the trajectory of a pandemic and inspired all manner of conspiracy theories.

Two of those shots prompt a recipient’s own cells to manufacture a key piece of the coronavirus by following instructions encoded in messenger RNA, or mRNA for short. The vaccines developed by Pfizer and Moderna have revolutionized our approach to immunizations, and they’ve done so with blinding speed.

That’s left many people yearning for something a bit more old-school.

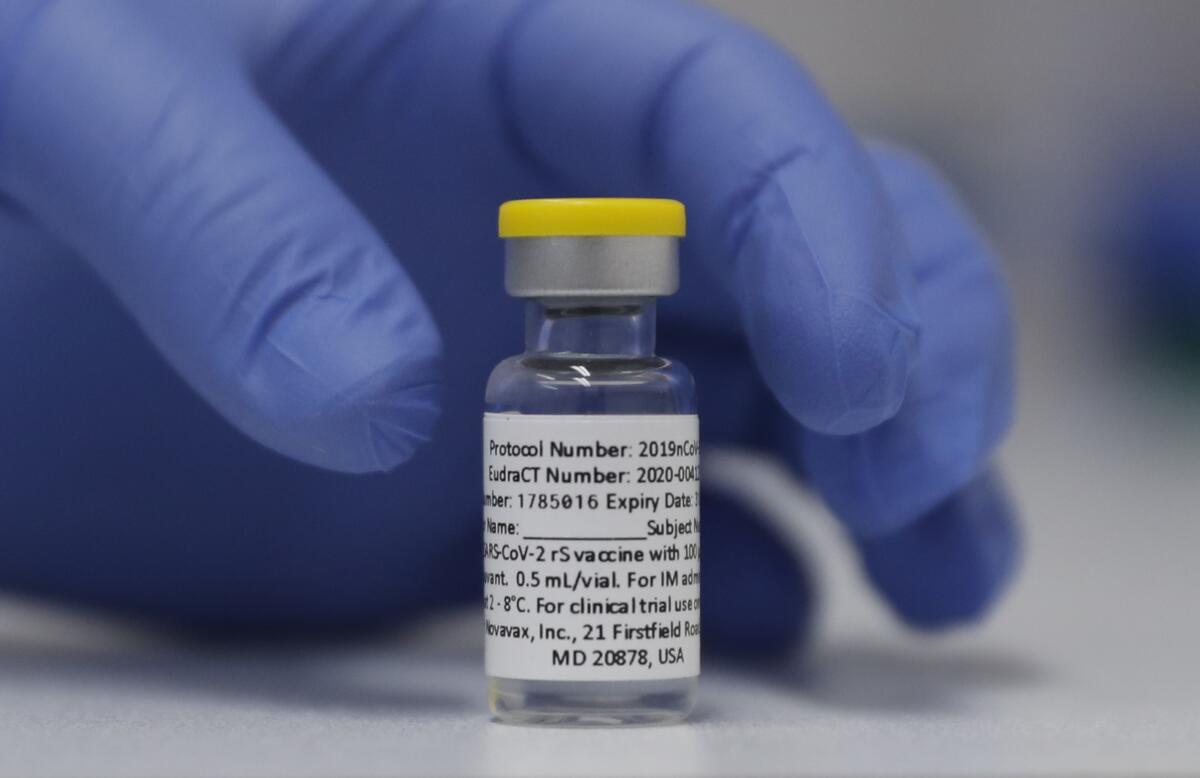

A COVID-19 vaccine from Novavax could fit that bill. In a world of newfangled ideas about training the immune system to spot and defend against an invading virus, the Novavax vaccine does it the old-fashioned way: by introducing an exact replica of the coronavirus spike protein into the bloodstream to show the immune system what the invader looks like.

Add in an “adjuvant” — an immune-boosting substance made from the purified bark of a South American tree — and, voilà! You’ve got the type of vaccine Americans have been taking for years to protect against familiar scourges like influenza and shingles.

Yes, there are nanoparticles and synthetic “recombinant proteins” involved. Legions of precisely uniform spike particles are manufactured not inside chicken eggs but in the cells of the Army caterpillar. These are hallmarks of a 21st century vaccine, one that was developed and tested under the aegis of Operation Warp Speed.

But Novavax touts its technology as a “well-known and established platform” for building vaccines. It expects its product known as NVX-CoV2373 to be embraced by Americans who are still suspicious of the mRNA mainstays, or are disinclined to turn to them as boosters.

With so much false information circulating about the coronavirus outbreak, health officials are trying to set the record straight. Here’s why that can backfire.

Those skeptics run the gamut, from people who think the mRNA vaccines were developed and tested too quickly to detect potential long-term side effects (a plausible concern) to those who believe they implant movement-tracking microchips into recipients’ bodies (a fear without any supporting evidence). In between are folks worried about the vaccines’ impact on fertility (current evidence shows no reason to be concerned) and those afraid that they alter a recipient’s DNA permanently (not possible, since the vaccine doesn’t enter a cell’s nucleus, where DNA resides).

Some people “may prefer tried and true technologies” for COVID-19 vaccines, said Dr. Filip Dubovsky, the chief medical officer of Novavax. While declaring himself a fan of mRNA vaccine technology, he added that others “may not like the concept of ... turning their body into a little vaccine factory.”

If made available, the Novavax vaccine might induce some of the millions of still-unvaccinated Americans to roll up their sleeves at last. “And when everybody gets vaccinated thoroughly, that’s when we get to tamp down” the coronavirus’ spread, he said.

Dr. Gregory Poland, a Mayo Clinic vaccinologist who has consulted with Novavax and other COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers, described NVX-CoV2373’s marketing niche a bit more directly.

“This would not be a ‘genetic vaccine,’” Poland said. “And people wary of ‘genetic vaccines’ might find it more appealing.”

That’s not its only upside. The Novavax vaccine does not seem to induce the rare but potentially serious type of heart inflammation associated with the mRNA vaccines. Nor does it cause the strong reactions that prompted some people who got the mRNA vaccines to put off their booster shots. Plus, some anti-abortion activists who refuse to take the mRNA vaccines because they were developed with cells lines derived from an aborted fetus would see it as an acceptable alternative.

The company behind a COVID-19 vaccine will miss a target for giving doses to the U.N.-backed effort to deliver shots to poorer countries.

But first, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration needs to authorize the vaccine for emergency use, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention must recommend it.

Why that has taken so long is a mystery. The Novavax vaccine — known commercially as Nuvaxovid or Covavax — is already authorized for emergency use in 28 countries and endorsed by the World Health Organization.

“This is a very good vaccine, but the FDA has slow-walked it every step of the way,” said Georgetown University’s Lawrence Gostin, an expert in public health law. Manufacturing hiccups raised early concerns among U.S. regulators. But those have long since been resolved, and Novavax has said it is on track to produce 2 billion doses this year.

Unlike the shots made by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, NVX-CoV2373 doesn’t require refrigeration at ultra-cold temperatures. It is formulated so that it does not need to be reconstituted, making it easier to administer by less-skilled handlers. And it can be produced cheaply and reliably by pharmaceutical manufacturers across the world.

All of those attributes make it likely that the Novavax vaccine will play an important role in running up vaccine coverage in the world’s low- and middle-income countries.

“Having the FDA authorize it in the United States would boost confidence in this vaccine globally,” Gostin said. That, in turn, could help avert surges and impede the emergence of new coronavirus variants, he said.

COVID-19 patients who take months to overcome their coronavirus infections despite treatment can become incubators of dangerous new strains.

One forward-looking move by Novavax could make its candidate a bit more appealing to U.S. regulators.

The packaging of its immunological payload is so efficient that it leaves room to protect against more than one disease. The company, which has a long history of making flu vaccines, announced in late April that it has begun human trials of a combination shot designed to induce immunity not only against COVID-19 but four different strains of influenza as well. It’s even possible a single Novavax shot could target multiple coronavirus variants in one shot, although Dubovsky said it makes sense to use the shots to protect “against two diseases with one jab.”

Novavax has produced and distributed 44 million doses of its purely COVID-19 vaccine since December 2021, and they’ve been going into arms in a wide range of countries. Indonesia, South Korea, Australia and the European Union were among its first big customers, and Japan joined the list last month. Manufacturers in Japan and India are are contracted to produce hundreds of millions of doses.

In clinical trials, side effects tied to NVX-CoV2373 have been mild and infrequent. The most common complaints were injection site pain, headaches and fatigue. And though mRNA vaccines have been linked to myocarditis in male adolescents and young adults, no cases of the potentially dangerous heart inflammation have been detected in the Novavax trials.

Though its widespread use abroad is building confidence in the vaccine’s safety, its effectiveness in protecting against COVID-19 — and especially against illness caused by the Omicron variants that now dominate the world — will be an object of intense scrutiny by U.S. regulators when they meet on June 7.

Deciding how many Americans we are willing to let die of COVID-19 each year is necessary to put the pandemic behind us.

One of the two clinical trials the Food and Drug Administration and its vaccine advisory committee will examine involved 30,000 adults in the United States and Mexico, and it found the shots 100% effective in protecting against mild and moderate cases of COVID-19.

But that trial was conducted at a time when the original coronavirus strain was waning, and the Alpha variant and others were becoming established. Against those variants, the vaccine efficacy declined somewhat, to 92.6%.

In a second clinical trial conducted in U.S. and Mexican adolescents ages 12 to 17, the Novavax vaccine had an overall efficacy of 80% in preventing COVID-19, largely against the trickier Delta variant. When compared with adults who got the vaccine, the teens’ immune responses were about two to three times higher against all variants studied, suggesting it may be well-suited to younger Americans.

Novavax has not submitted a clinical trial that reflects its vaccine’s success against the Omicron variant. Dubovsky argued that the vaccine’s steady rate of efficacy across a wide range of variants augurs well for its ability to protect not only against Omicron, but against others that may crop up.

Gostin said U.S. officials “have just bet the farm on the two mRNA vaccines,” but it’s not too late to add others to the mix. Use of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine has stalled since the CDC declared the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines “preferred ... in most circumstances.” AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine has never been evaluated by the FDA for the U.S. market, even though 2.6 billion doses have been delivered across the globe.

“I think that’s unwise,” Gostin said.