Study of mutations in cancers may point the way to personalized treatments

- Share via

Scientists have analyzed the full genetic blueprints of more than 18,000 cancer samples, finding new patterns of mutations that could help doctors provide better, more personalized treatment.

Their study, published Thursday in the journal Science, isn’t the first to do such comprehensive “whole genome” analyses of cancer samples. But no one has ever done so many.

“This is the largest cohort in the world. It is extraordinary,” said Serena Nik-Zainal of the University of Cambridge, who was part of the team.

More than 12,200 surgical specimens came from patients recruited from the U.K. National Health Service as part of a project to study whole genomes from people with common cancers and rare diseases. The rest came from existing cancer data sets.

Researchers were able to analyze such a large number because of the same improvements in genetic sequencing technology that recently allowed scientists to finally finish decoding the entire human genome — more capable, accurate machines.

“We can really begin to tease out the underpinnings of the erosive sort of forces that go to sort of generate cancer,” said Andrew Futreal, a genomic medicine expert at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston who was not involved in the study.

Roughly half of cancer deaths in the United States could be prevented or forestalled if all Americans quit smoking, cut back on drinking, maintained a healthful weight and got at least 150 minutes of exercise each week, according to a new report.

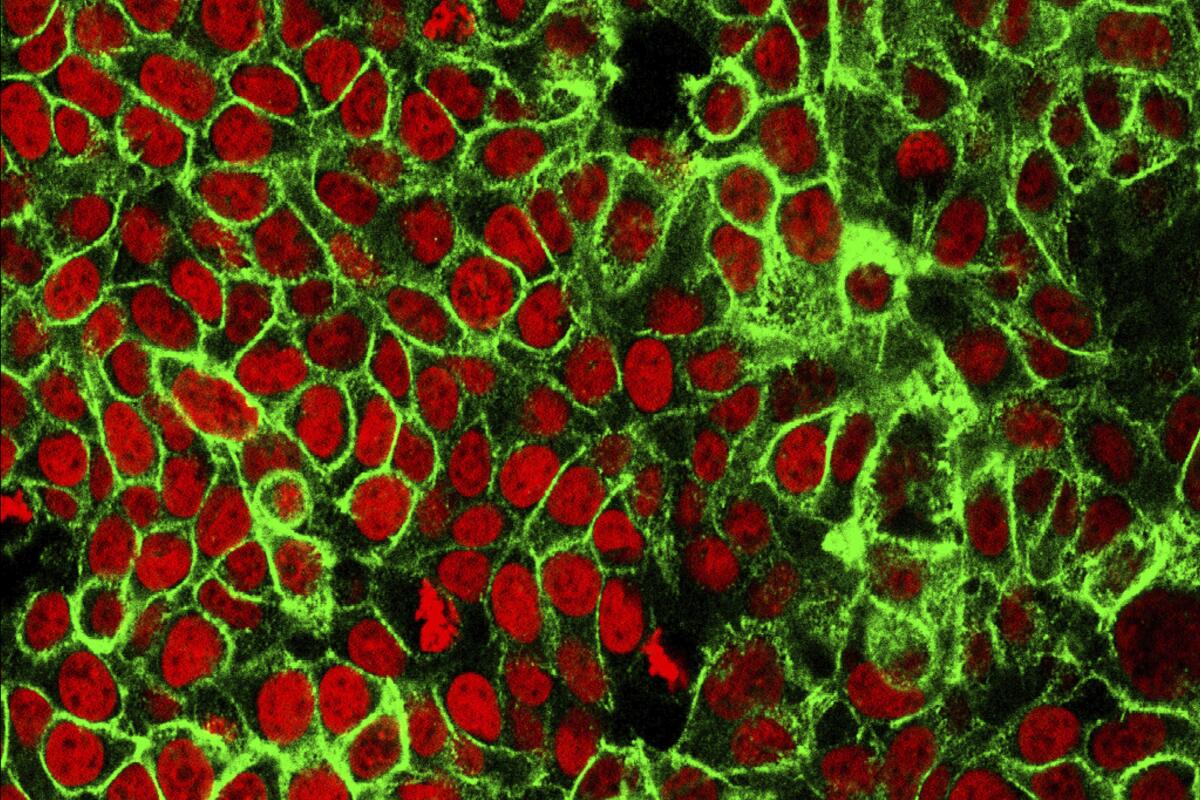

Cancer is a disease of the genome, or full set of instructions for running cells, that occurs when changes in a person’s DNA cause cells to grow and divide uncontrollably. In 2020, there were about 19 million new cancer cases worldwide.

For the study, researchers looked at 19 types — breast, colorectal, prostate, brain and others — and identified 58 new clues to the causes of cancer called “mutational signatures” that contribute to the development of the disease. They also confirmed 51 of more than 70 previously reported mutation patterns, Nik-Zainal said.

Some arise because of problems within a person’s cells; others are sparked by environmental exposures such as ultraviolet radiation, tobacco smoke or chemicals.

Knowing more of them “helps us to understand each person’s cancer more precisely,” which can help guide treatment, Nik-Zainal said.

Even in a world with a pristine environment, no cigarettes and the ability to fix faulty genes inherited from our parents, most of the cancers diagnosed today still would occur thanks to a combination of biology and bad luck.

Genetic sequencing is already being woven into cancer care as part of the growing trend of personalized medicine, or care based on a patient’s genes and specific disease. Now doctors will have much more information to draw from when they look at individual cancers.

To help doctors use this information, researchers developed a computer algorithm that will allow them to find common mutation patterns and seek out rare ones. Based on a particular pattern, Nik-Zainal said a doctor may suggest a certain course of action, such as getting immunotherapy.

Futreal said the data can also show doctors what tends to happen over time when a patient develops a cancer with a certain mutation pattern — helping them intervene earlier and ideally stop the developing disease in its tracks.