CDC shifts pandemic goals away from reaching herd immunity

- Share via

Since the earliest days of the pandemic, there has been one collective goal for bringing it to an end: achieving herd immunity. That’s when so many people are immune to a virus that it runs out of potential hosts to infect, causing an outbreak to sputter out.

Many Americans embraced the novel farmyard phrase, and with it, the projection that once 70% to 80% or 85% of the population was vaccinated against COVID-19, the virus would go away and the pandemic would be over.

Now the herd is restless. And experts at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have set aside herd immunity as a national goal.

The prospects for meeting a clear herd-immunity target are “very complicated,” said Dr. Jefferson Jones, a medical officer on the CDC’s COVID-19 Epidemiology Task Force.

“Thinking that we’ll be able to achieve some kind of threshold where there’ll be no more transmission of infections may not be possible,” Jones acknowledged last week to members of a panel that advises the CDC on vaccines.

Vaccines have been quite effective at preventing cases of COVID-19 that lead to severe illness and death, but none has proved reliable at blocking transmission of the virus, Jones noted. Recent evidence has also made clear that the immunity provided by vaccines can wane in a matter of months.

The result is that even if vaccination were universal, the coronavirus would probably continue to spread.

“We would discourage” thinking in terms of “a strict goal,” he said.

A study of 780,000 veterans shows a dramatic decline in effectiveness for all three COVID-19 vaccines in use in the U.S.

To Dr. Oliver Brooks, a member of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, it was a sobering new message, with potentially worrisome effects.

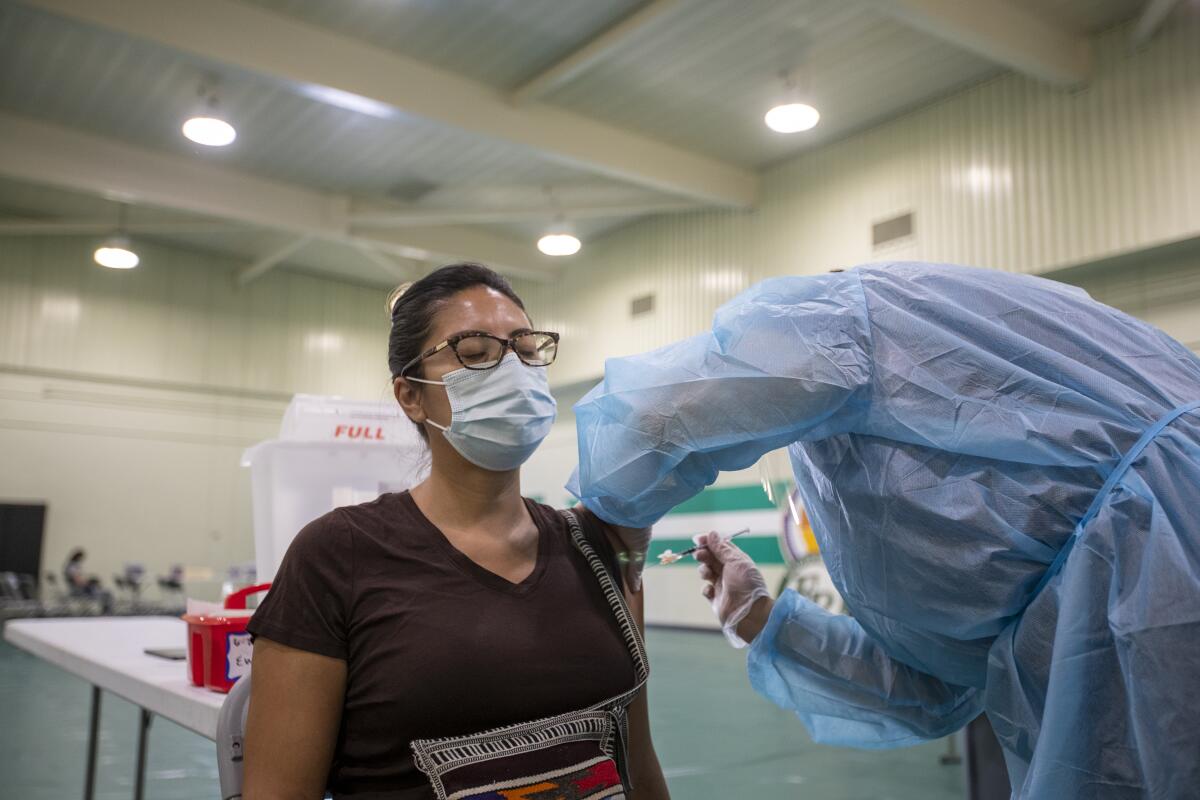

With just 58.5% of all Americans fully vaccinated, “we do need to increase” the uptake of COVID-19 shots, said Brooks, chief medical officer of Watts Healthcare in Los Angeles. Unfortunately, he said, Jones’ unexpected admission “almost makes you less motivated to get more people vaccinated.”

Brooks said he worries that as the CDC backs off a specific target for herd immunity, it will take the air out of efforts to run up vaccination levels.

And if public health officials stop talking about the “herd,” people may lose sight of the fact that vaccination is not just an act of personal protection but a way to protect the community.

A public tack away from the promise of herd immunity may also further undermine the CDC’s credibility when it comes to fighting the coronavirus.

On issues ranging from the use of masks to how the virus spreads, the agency has made some dramatic about-faces over the course of the pandemic. Those reversals were prompted by new scientific discoveries about how the novel virus behaves, but they’ve also provided ample fuel for COVID-19 skeptics, especially those in conservative media.

Social media influencers across the U.S. are being paid to try to change the minds of vaccination-averse people at a neighborhood level.

“It’s a science-communications problem,” said Dr. John Brooks, chief medical officer for the CDC’s COVID-19 response.

“We said, based on our experience with other diseases, that when you get up to 70% to 80%, you often get herd immunity,” he said.

But the SARS-CoV-2 virus didn’t get the memo.

“It has a lot of tricks up its sleeve, and it’s repeatedly challenged us,” he said. “It’s impossible to predict what herd immunity will be in a new pathogen until you reach herd immunity.”

The CDC’s new approach will reflect this uncertainty. Instead of specifying a vaccination target that promises an end to the pandemic, public health officials hope to redefine success in terms of new infections and deaths — and they’ll surmise that herd immunity has been achieved when both remain low for a sustained period.

“We want clean, easy answers, and sometimes they exist,” John Brooks said. “But on this one, we’re still learning.”

Scientists are trying to decide who should be eligible for COVID-19 booster shots, but they’re missing key data that would help them.

Herd immunity was never as simple as many Americans made it out to be, said Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania and an expert on the challenges of communicating science to increasingly skeptical — and often conspiracy-minded — citizens.

It’s an idea that emerged about a century ago from the field of livestock medicine. Epidemiologists now calculate it with a standard equation. But like many tools that model a complex process with math, it makes some simplifying assumptions.

For instance, it assumes an unrealistic uniformity in the behavior of individuals and groups, and in the virus’ ability to spread from person to person.

So it doesn’t reflect the diversity of population density, living arrangements, transportation patterns and social interactions that makes Los Angeles County, for instance, so different from Boise County, Idaho. Nor does it account for the fact that Boise County, where less than 35% of adults are fully vaccinated, gets no protection from L.A. County’s 73% vaccination rate among adults.

“Humans are not a herd,” Jamieson said.

Public health leaders would have been better served by framing their vaccination campaigns around the need for “community immunity,” she said. That would have gotten people to think in more local terms — the ones that really matter when it comes to a person’s risk of infection, she added.

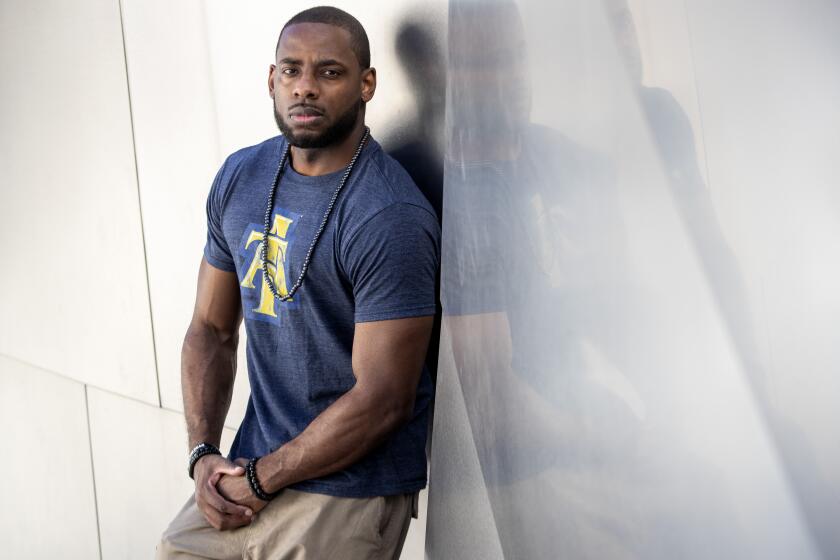

Vaccination rates are up, but there’s fear Black and Latino men will continue waiting until they almost die from COVID-19 or watch people they know die before getting vaccinated.

Changes in the coronavirus itself have also made herd immunity a moving target.

The calculation that produced a herd immunity estimate of 70% to 85% rests heavily on the innate transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2. But with the emergence of new viral strains like the Alpha and Delta variants, the virus’ ability to jump from person to person has escalated dramatically in the last year.

In addition, herd-immunity calculations presume that when people gain immunity, they remain immune for a known period of time. But it’s become clear that neither vaccination nor natural infection confers lasting protection. Booster shots or a “breakthrough” case might, but for how long is still unknown.

That’s just the way science works, said Raj Bhopal, a retired public health professor at the University of Edinburgh who has written about the maddening complexity of herd immunity.

For any agency engaged in public messaging, “it’s very hard to convey uncertainty and remain authoritative,” Bhopal said. “It’s a pity we can’t take the public along with us on that road of uncertainty.”