Should the FDA move faster on COVID-19 vaccines for young children?

- Share via

Whether you’re the parent of a young child, a school employee or just someone who pulls your mask up a little tighter at the sight of an approaching gaggle of kids, you’re probably asking yourself this question with a growing sense of urgency:

How soon can the youngest Americans safely get their jab?

Get ready to hear calls for patience and the oft-repeated mantra of pediatric medical professionals: Kids are not small adults.

In other words, don’t assume that because COVID-19 vaccines have been shown to protect adults and adolescents quite safely that the same vaccines in the same doses will work just as well for younger children.

Children’s bodies — their organs, their muscles and bones, and their metabolic and immune systems — function differently than those of adults. That means they can respond very differently to adult medicines in adult doses.

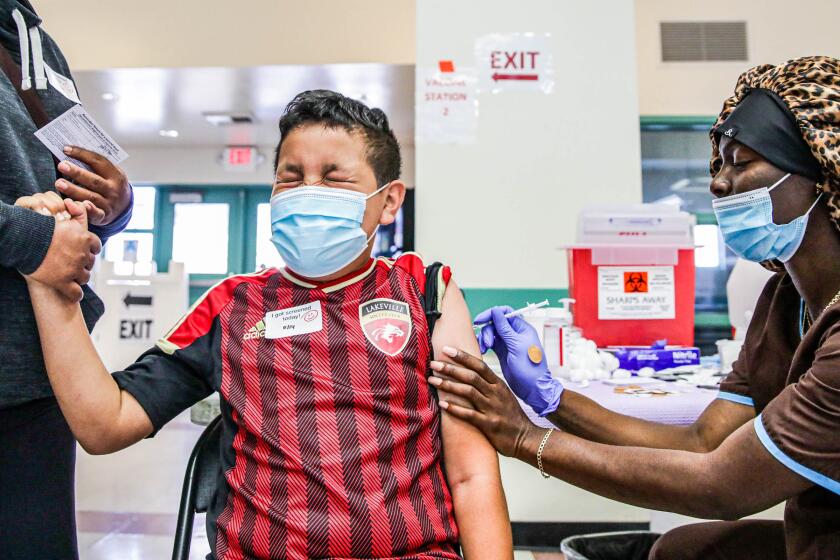

So before COVID-19 vaccines can be cleared for the 28 million American children between the ages of 5 and 11 and the 20 million who are even younger, regulators need solid evidence that the shots are safe and that they reduce the risk of disease.

That evidence will have to come from clinical trials that will be scrutinized by the experts at Food and Drug Administration. That’s typically an exacting and deliberate process, often taking years.

But in the midst of a pandemic sent into overdrive by the Delta variant, “exacting and deliberate” is beginning to sound more like “slow and bureaucratic.”

Now that Comirnaty has full FDA approval, doctors can recommend the COVID-19 shot to anyone for ‘off-label’ use, including children under 12.

Between late June and mid-August, as the Delta variant solidified its grip on the nation, the rate at which children were hospitalized for COVID-19 surged almost fivefold. The nation’s pediatricians were growing impatient.

“The Delta variant has created a new and pressing risk to children and adolescents across this country,” the American Academy of Pediatrics wrote in an Aug. 5 letter to the FDA. The doctors exhorted the agency “to carefully consider the impact of its regulatory decisions on further delays in the availability of vaccines for this age group.”

The FDA is keenly aware of the pressure. It responded Friday with the release of an unusual public statement that acknowledged the urgency of its mission and promised to review clinical trial data “as quickly as possible, likely in a matter of weeks rather than months.”

Here’s a closer look at where we go from here.

Aren’t some COVID-19 vaccines already available to American kids?

Yes. The one made by Pfizer and BioNTech has received full approval for people 16 and older and has been authorized for emergency use in 12- to 15-year-olds.

That’s it?

So far. Pfizer said it expects to get the first results from its trial in younger children to the FDA later this month or in early October. Once those data are submitted, the FDA can begin to evaluate it.

A second vaccine made by Moderna has won provisional approval for adolescents 12 to18 in Canada, Europe and Japan. The company has filed to gain the FDA’s blessing for emergency use in kids in the U.S. as young as 12, saying that its clinical trial results were “consistent with a vaccine efficacy of 100%.” An advanced-stage trial in 4,000 children ages 5 to 11 has just completed enrollment.

The Johnson & Johnson vaccine is still being tested on adolescents 12 to 17.

What’s holding things up?

Anxious over the emergence of a couple of rare side effects, the FDA in midsummer went back to vaccine makers and told them to add more kids to their trials. Regulators also proposed that the trials track them for longer than they had initially planned. That would give safety experts a better chance of detecting rare side effects, as well as very delayed reactions to vaccine.

A growing contingent of medical experts is questioning the conventional wisdom that healthy children should get COVID-19 shots as soon as possible.

Pfizer and Moderna responded by roughly doubling the size of their trials for younger children.

The sudden shift alarmed Stanford pediatrician Dr. Yvonne Maldonado, who chairs the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Committee on Infectious Diseases and is working on one of Pfizer’s pediatric clinical trials.

“It would have extended the timeline by several months,” she said. And as a statistical matter, a trial with twice as many kids would probably still miss a rare side effect. Plus, since post-vaccine reactions are most likely to take place in the two months after a shot, lengthening the follow-up was unlikely to add any insight, she said.

Why would regulators risk a delay?

The challenge with clinical trials is that “you are essentially trying to predict the safety of a vaccine in billions of children by looking at its safety in thousands of children,” said Dr. Paul Offit, a vaccine expert at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

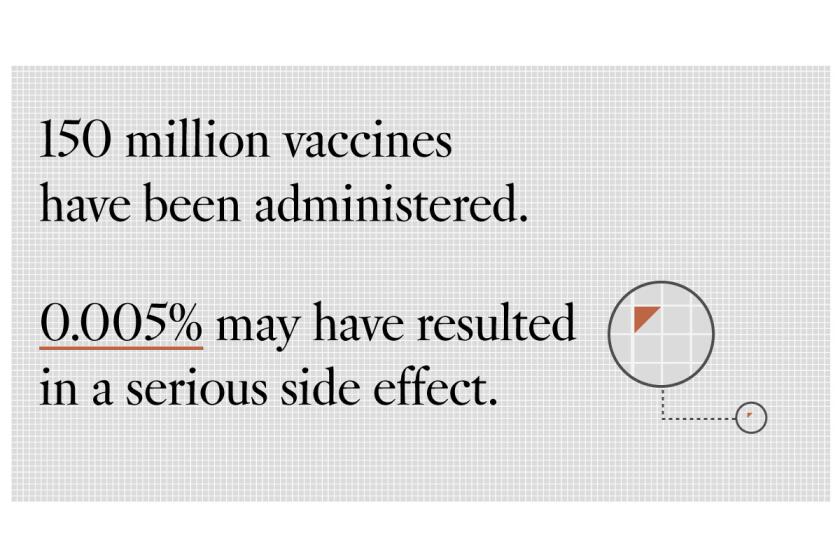

Questions about COVID-19 vaccines’ safety have led to hesitancy for some Americans. Experts say there is almost zero cause for concern.

It’s important to try to detect rare adverse effects, said Offit, who has advised both the FDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Even if a dreadful side effect occurred in only 1 in 1 million kids, it could mean vaccine-related hospitalizations or death for as many as 120 children in the U.S. alone.

But during a raging pandemic in which children are being hospitalized at growing rates, it’s costly to extend trials in hopes of catching faint safety signals. “It’s frustrating that children are back in school and that they’re not vaccinated,” Offit said.

Is the FDA looking for something specific?

Yes. Regulators are particularly keen to know more about a condition called myocarditis, which is swelling or inflammation of the heart muscle.

In early June, just a month after the Pfizer vaccine became available to 16- and 17-year-olds, the CDC documented a slight rise in cases of myocarditis in recently vaccinated people.

Seen mostly in boys and men younger than 30, the symptoms were generally mild and went away in a few days either on their own or with over-the-counter medication. The long-term effects of a mild case of myocarditis are not clear.

At the same time, myocarditis is often seen in children and young adults who are hospitalized with COVID-19 — so preventing the disease with a vaccine may be a net gain. Research is ongoing, and pediatricians are unsure whether younger boys would be as prone to the side effects as their older brothers.

After a detailed briefing in June, a CDC advisory panel recommended the vaccine for all eligible adolescents. But the panel cautioned that people who developed myocarditis after their first dose should consider delaying their second dose until they had recovered or the condition was better understood.

Is that it?

There’s always the possibility of an entirely unforeseen side effect, such as the blood clots that emerged in a vanishingly small number of younger women who received the J&J vaccine. Although administration of that vaccine was briefly paused while the risk was investigated, shots were quickly resumed.

A CDC advisory panel is grappling with the best way to “do no harm” regarding Johnson & Johnson’s COVID-19 vaccine and its risk of blood clots.

In the middle of a pandemic, detecting rare or unforeseen side effects is a task best left until after a vaccine is authorized and large numbers of diverse people begin to get it, Maldonado said.

“This wait-and-see approach assumes that you know what you’re waiting for,” Maldonado said. “We don’t have the luxury of waiting three to five years for whatever that magical endpoint might be.”

As long as children remain unvaccinated, they will continue to transmit the virus and keep the pandemic alive, she added.

Won’t the FDA’s extra scrutiny ensure that vaccines are safe for kids?

With vaccines — especially ones for children — medical ethicists demand a particularly high standard of safety. After all, vaccines are given to healthy people who, if they’re lucky, might never be exposed to the disease-causing pathogen in the first place.

That’s why, in the best of times, tolerance for risky vaccines is very low. But now, regulators face a quandary.

Public mistrust continues to suppress vaccine uptake and to drive COVID-19 hospitalizations. If the FDA redoubles its efforts to detect vaccine-related side effects, will it shore up public confidence in their oversight? Or will it erode faith in vaccines by chasing problems that may prove harmless?