Coronavirus infections among school-age kids rose in September after classes resumed

- Share via

Keen to send the nation’s kids back to reopened schools, President Trump has called children “virtually immune,” “essentially immune” and “almost immune” to the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

But a new report by researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention underscores how wrong those assertions are.

Children can catch, suffer and die from the coronavirus, according to the report. Between March 1 and Sept. 19, at least 277,285 schoolchildren in 38 states tested positive for the virus.

And 51 of them — including 20 youngsters 5 to 11 years old — died of COVID-19. In all, 3,189 children ages 5 to 17 were hospitalized.

With more than 56 million U.S. kids attending primary and secondary schools this fall, understanding how the coronavirus affects school-age children “might inform decisions about in-person learning and the timing and scaling of community mitigation measures,” the CDC researchers wrote.

For instance, throughout the spring and summer, the incidence of coronavirus infections was about twice as high among middle and high schoolers as it was for elementary school students.

The median age of people with COVID-19 in the U.S. has declined, with adults in their 20s now accounting for more cases than people in any other age group.

School-age children with asthma and other chronic lung diseases accounted for roughly 55% of those who tested positive, and almost 10% had some kind of disability.

As with adults, Latino children far outpaced their share of the population in testing positive, accounting for 46% of those who tested positive during the 6½-month period studied by the CDC.

And although Trump has said he does not believe school-age children get sick from the virus, at least 58% of those who tested positive had COVID-19 symptoms at the time they were tested, the CDC researchers reported.

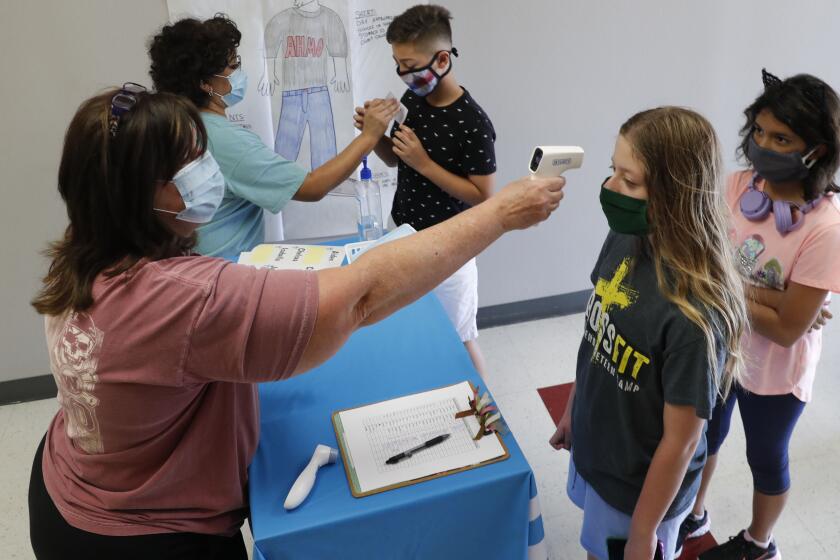

The new research, published Monday in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, is one of the public health agency’s first efforts to count and characterize coronavirus infections in the nation’s school-age population. As a new school year gets underway and some schools reopen to students, it will be “critical to have a baseline for monitoring trends in COVID-19 infection among school-aged children,” the authors wrote.

William Hanage, an infectious diseases researcher at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, said it’s no surprise that adolescents, who are more independent and less likely to maintain social distance, would have higher rates of infection. At the same time, he added, the report “almost certainly underestimates cases in the younger age group.”

When and where schools reopen and students return to classrooms, opportunities for transmission will escalate. And this report “underlines that kids do transmit,” said Hanage. The result — a rise in cases among young learners — is predictable, he suggested.

Here’s what scientists know about kids’ potential to spread the coronavirus and the risks of sending them back to school amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Already, a few of those trends were clear. Others will require further data and closer dissection.

The CDC researchers tallied a weekly average of 37.4 cases for every 100,000 adolescents ages 12 to 17, compared with a weekly average of 19 cases per 100,000 children ages 5 to 11. The younger kids were slightly less likely than their older peers to have recorded the presence of symptoms at the time they were tested, by a margin of 56.1% vs. 59.6%. But in 37% of all cases cited, symptom status was “missing or unknown.”

The summer months brought spikes in infections among school-age children as a whole, and especially among adolescents, the CDC team found. But as classes have resumed across the nation — some remotely, some in person — a summer-long run-up in positive coronavirus tests may have begun to reverse itself.

Between Memorial Day and Labor Day, the incidence of weekly infections went on a wild roller-coaster ride, reaching a peak of nearly 38 cases per 100,000 school-age children in mid-July before leveling off at about 34 cases per 100,000 kids in late August. By the first full week of September, cases fell to 22.6 per 100,000.

However, as the school year got going in earnest, the first hints of spread became apparent. By the week that ended Sept. 19, the incidence of weekly cases was back up to 26.3 per 100,000 children. The incubation period for the coronavirus is typically four to five days, though it could be as long as two weeks, according to the CDC.

Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease and preventive medicine expert at Vanderbilt University, said that despite the unresolved details, the thrust of the report is clear: Children are not invulnerable.

“This stands in stark contrast to what we’ve heard time and time again from politicians: that this disease does not affect children. Really? Here, we see there are at least 51 families who will be grieving for a very long time,” Schaffner said.

More than 3,000 other children have been hospitalized, he added, “putting their families in agony.”