Coronavirus kills some people and hardly affects others: How is that possible?

- Share via

The new coronavirus is not an equal opportunity killer.

We know COVID-19 is more deadly the older you get. It’s also more dangerous for those who have chronic lung disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, weakened immune systems and other underlying health issues.

And yet our news feeds are full of stories about seemingly healthy young people who are quickly struck down, like 32-year-old Jéssica Beatriz Cortez or a 25-year-old pharmacy tech from La Quinta.

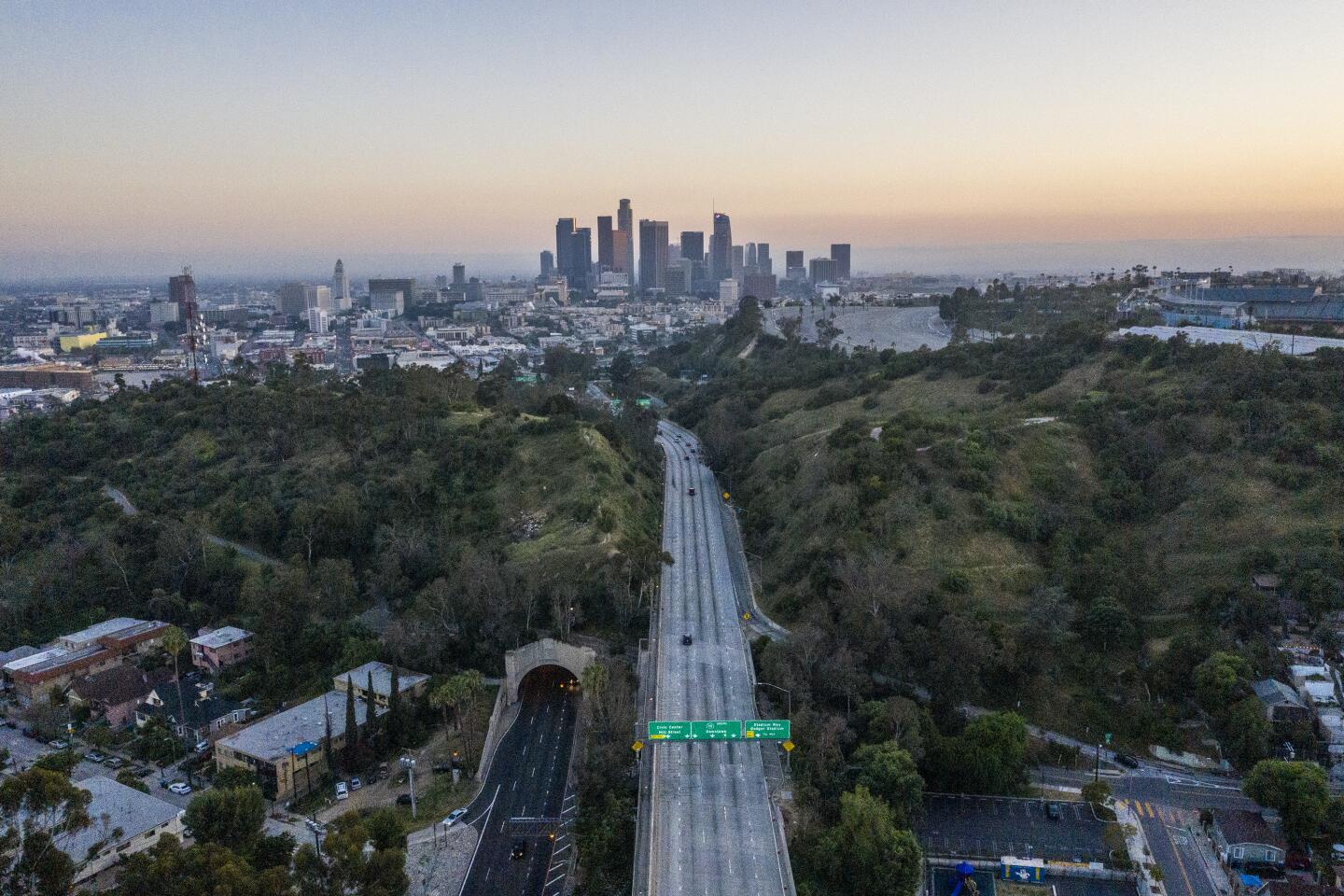

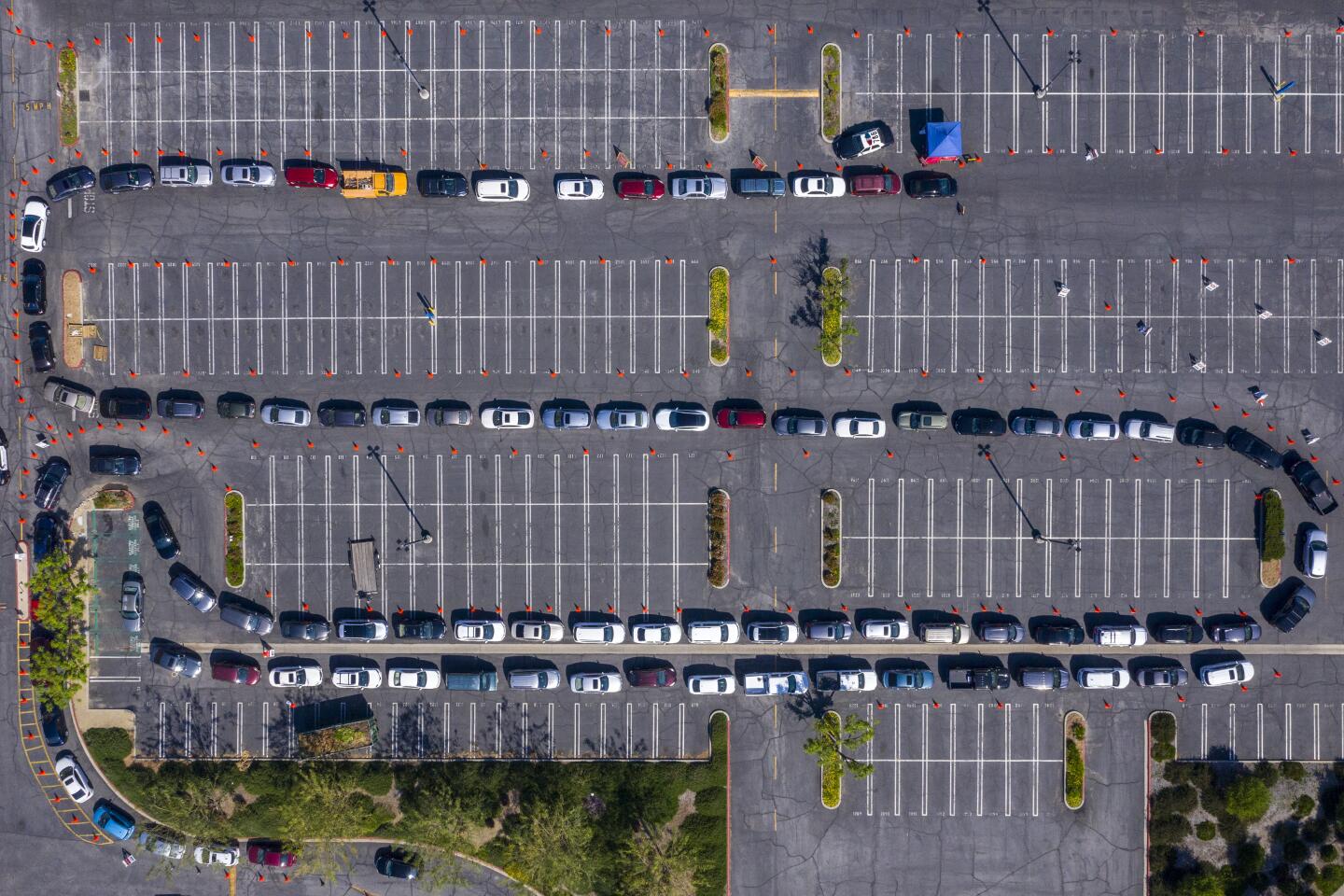

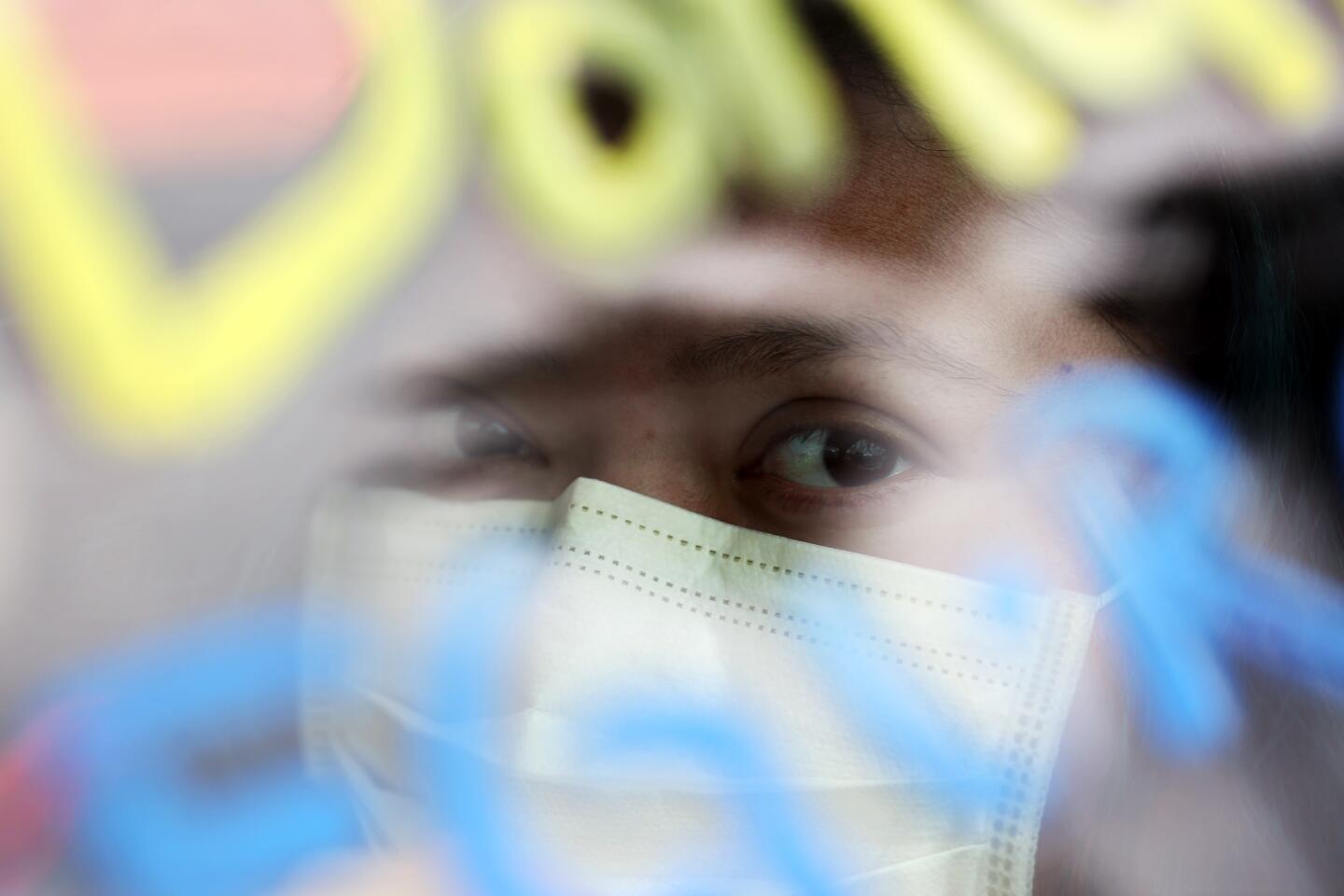

These are some of the unusual new scenes across the Southland during the coronavirus outbreak.

These tragic deaths seem all the more confounding when you consider a flurry of new scientific studies that suggest as many as 20% of people who are infected with the coronavirus — and possibly many more — never develop any symptoms.

This lucky group is spared the dry cough, fever and body aches we now associate with COVID-19, even while the virus proliferates in their bodies and potentially spreads to others.

This new understanding about the role of “silent spreaders” is why the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other health authorities are now suggesting that people wear masks when they leave the house. The recommendation is primarily designed to keep asymptomatic people from unwittingly spreading a disease they may not even know they have.

But how can the same virus affect people so differently — killing some while leaving others blissfully unaware that they have been infected at all?

The Los Angeles Times spoke with two infectious disease experts — Dr. Otto Yang of UCLA and Dr. Edward Jones-Lopez of USC — to answer that question.

‘We may be moving gently at this point toward the Asian culture,’ one health expert says of everyday mask-wearing.

One thing to keep in mind before we continue: It is possible that the information you read below will be contradicted in the coming weeks or that gaps in knowledge today will soon be filled as scientists continue to study the virus.

“There is an explosion of research about this, and what we know about it is changing almost by the hour,” Jones-Lopez said.

Here’s what they know so far:

What happens when a person is infected with the new coronavirus?

OY: The coronavirus, like all viruses, is basically just a piece of genetic information that enters into a cell and then hijacks its machinery so that the cell starts producing the virus’ genetic material rather than its own.

EJL: Keep in mind that not all exposures lead to infections. If an infection occurs, it means that the virus has identified the type of cell it needs to establish an infection.

Once an infection has been established, the virus replicates very quickly and is disseminated through the blood.

How does the coronavirus make people sick?

OY: It makes people sick in two ways. Initially, people get fever and cough, and some other symptoms. In this phase, the virus is causing direct damage and infection to cells in the lungs.

Some patients get better after this point, but others get severe inflammation in their lungs and other organs, and that can be life-threatening. This appears to be the immune system reacting severely to the virus.

But there are varying degrees of how sick people get with the disease.

EJL: The data tell us that about 50% of people who acquire the infection develop either no symptoms at all or very mild symptoms to the point that they don’t even know they have it.

Among the other 50%, the estimates are that about 30% develop overt symptoms from mild to moderate.

The last 20% are the ones that develop severe symptoms, and those are the ones that are ending up in the hospital.

Why would the virus affect people so differently?

OY: The simple answer is we don’t know for sure. The big risk factors are diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease and age.

But how each of those contribute to mortality rates is not entirely clear, and they may not contribute in the same way.

EJL: It may not be so much an issue of age as overall health because there are 20-, 30- and 50-year-olds who, despite their relatively young age, are getting very sick.

Older people tend to accumulate more health issues. That is probably one of the reasons that older patients are not doing so well.

If you’ve been infected with the coronavirus, the chances that you will become critically ill depend on many factors.

But we know that some people who seem healthy are getting very sick as well. What’s causing that?

EJL: We don’t really understand the predictors for who gets critically ill. It may be related to how a person’s particular immune system reacts with the virus that is responsible for how severely it will affect them.

OY: I think of the immune system like the police and the virus like criminals.

If the criminals are easily brought under control, then the police don’t do much collateral damage to the city. But if there is an all-out war with equally matched sides, there is a lot of collateral damage. That’s what we are seeing in the sickest patients.

Is it surprising that the virus would affect people so differently? Do other viruses do that too?

EJL: It actually is somewhat typical, I would say. What’s different is that the coronavirus doesn’t seem to be affecting children in the same way for reasons we don’t understand yet.

That might be a very important scientific clue to investigate in the future.

There are a lot of unknowns. When do you expect to have more answers?

EJL: The virus first surfaced in China just four months ago, and we already have 50 papers published on coronavirus. That’s unheard of. We already know a lot, and it is very likely that in the next six months the knowledge base will multiply by many times.

OY: I’m going to quote Yogi Berra — predictions are really hard to make, especially about the future. But there is a lot of new information trickling out, and I think many of our questions will be answered in the next few months, and definitely within the next year or two.

Struggling renters need relief if the U.S. is going to avoid the kind of suffering and economic devastation that played out after the Great Recession.