Should you panic about the coronavirus from China? Here’s what the experts say

- Share via

It’s a virus scientists have never seen before. Health officials don’t know exactly where it came from, but it has traveled more than 7,000 miles since it was discovered late last month in central China. New infections are confirmed every day despite an unprecedented quarantine. The death toll is rising, too.

If this were a Hollywood movie, now would be time to panic. In real life, however, all that most Americans need to do is wash their hands and proceed with their usual weekend plans.

“Don’t panic unless you’re paid to panic,” said Brandon Brown, an epidemiologist at UC Riverside who has studied many deadly outbreaks.

“Public health workers should be on the lookout. The government should be ready to provide resources. Transmitting timely facts to the public is key,” Brown said. “But for everyone else: Breathe.”

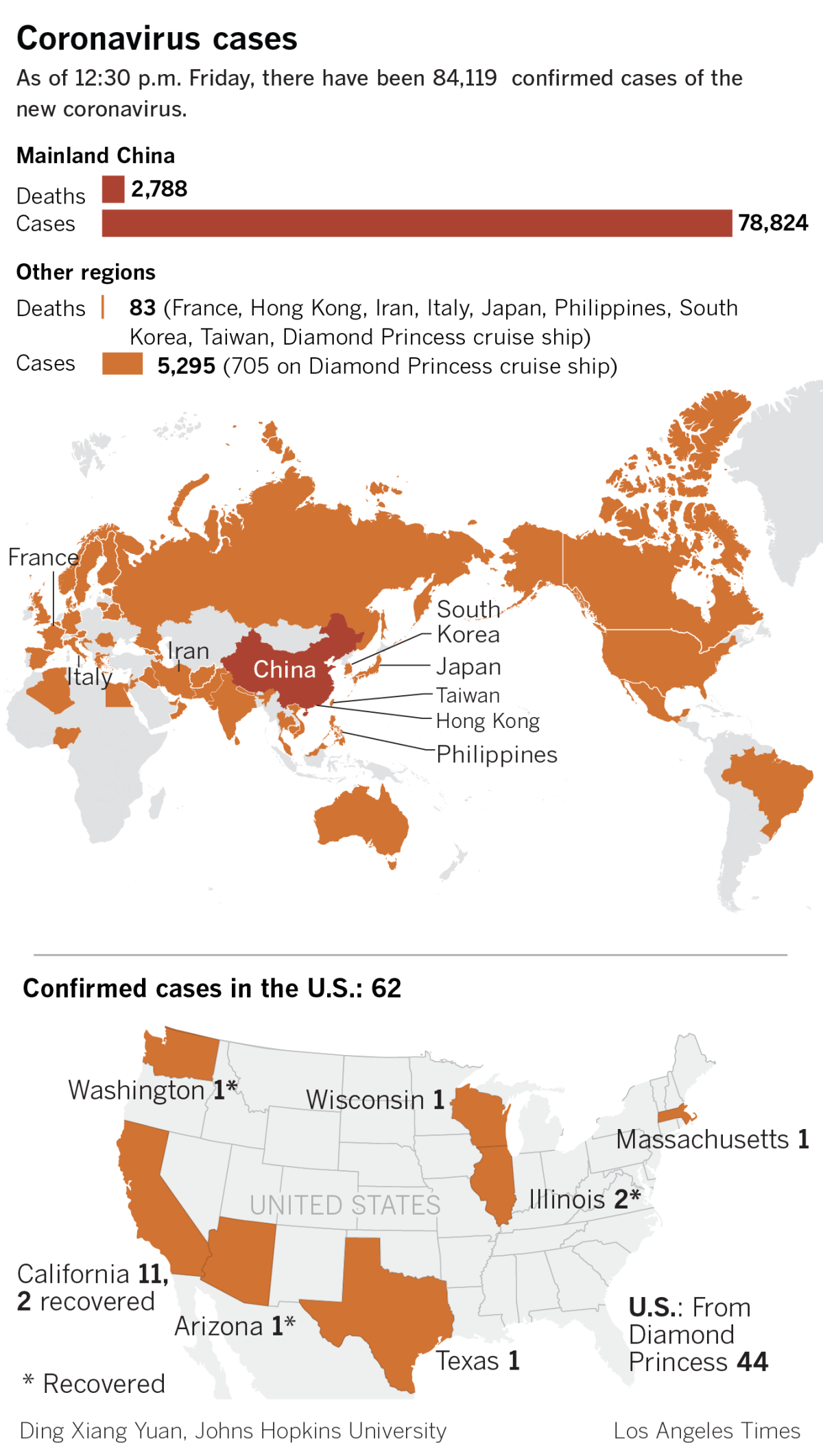

More than three weeks into the outbreak that has spread to at least 1,354 people in 11 countries and territories, scientists have learned some important things about the virus.

It is a coronavirus, which makes it a relative of the pathogens that cause severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, and Middle East respiratory syndrome, or MERS. Those diseases have sickened thousands of people around the world and caused hundreds of deaths.

Other coronaviruses result in nothing worse than a common cold.

In addition to humans, coronaviruses can sicken cows, pigs, cats, chickens, camels, bats and other animals. Most of the outbreak’s early victims said they had visited a large seafood and live animal market in the Chinese megacity of Wuhan, suggesting that the virus originated in another species before jumping to humans.

When experts examined the organism’s genetic code, they found a sequence that was entirely new to science. That means many people have not had a chance to develop sufficient natural immunity to the coronavirus that has been dubbed 2019-nCoV — an important consideration since vaccines take years to develop.

Fortunately, the virus seems to cause only minor symptoms — such as fever and difficulty with breathing — in people who are young and healthy. Most of the 41 deaths tied to the coronavirus to date have been in people who were at least 50 years old with underlying medical problems or weakened immune systems, Chinese officials said.

“We don’t have evidence yet to suggest this is any more virulent than the flu you see in the U.S. each year,” said said Dr. Michael Mina, an epidemiology researcher at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “Most people, with proper medical attention, will do just fine.”

In fact, it’s possible that hundreds or even thousands of people in China and elsewhere have been infected but have had such mild reactions that no one even noticed, said Dr. Tom Inglesby, director of the Center for Health Security at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Some might have fought off the bug without showing any outward symptoms at all.

“It’s too soon to know,” Inglesby said. “Often in new outbreaks, the most serious or severe cases are recognized first,” and that may result in a skewed picture of just how dangerous the virus truly is.

Epidemiologists are also trying to nail down when the new coronavirus gained the ability to jump directly from human to human. More than 85% of patients identified in the past week said they had not visited the Wuhan market that is believed to be ground zero for the outbreak. (The market is now closed.)

“It is clear the growing outbreak is no longer due to ongoing exposures at the Huanan seafood market,” according to the latest situation report from the World Health Organization.

Patients in Guangdong province have spread the virus to family members who had not traveled to Wuhan, which is about 600 miles away. The WHO also reports a few cases of hospital employees and other healthcare workers becoming sick after treating infected patients.

Public health officials said they expect to see human-to-human transmissions continue in the short term. That means new cases are sure to emerge throughout Asia, and even in the United States.

Information is spreading faster than the pathogen — and that’s just as novel.

The 2003 SARS outbreak that began in China’s Guangdong province in 2002 sickened 8,098 people and killed 774 in 29 countries by the time it ended in 2003. But in the outbreak’s early days, the Chinese government obfuscated the number of cases, hindering foreign leaders’ efforts to help citizens’ ability to protect themselves. The resulting public backlash prompted the dismissals of the country’s health minister and mayor of Beijing.

This time around, Chinese officials have moved swiftly to alert other countries to the outbreak’s developments. They’ve also shared the virus’ genetic sequence, which can help epidemiologists track its spread and make predictions about what it might do next.

“This is definitely not 2003,” said Rebecca Katz, the director of the Center for Global Health Science and Security at Georgetown University. “The speed with which this virus was identified is testament to that.”

Within 24 hours of receiving the coronavirus’s genome, the CDC programmed a real-time diagnostic test called an RT-PCR assay, said Dr. Nancy Messonnier, director of the agency’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. The tool quickly confirmed that a man in Washington state and a woman in Chicago were infected with 2019-nCoV and not some other pneumonia-causing virus. Other institutions around the world have used the genetic code to design similar tests.

That leads to another reason to avoid alarm: The rapidly rising case counts may be deceiving you. Before these new tools were developed, doctors had no surefire way to confirm a case of 2019-nCoV. That means that, as testing becomes available, infections appear to skyrocket.

“You’ll see a spike of 300 cases, but maybe those 300 were there all along,” Mina said. “This might not reflect a growing epidemic as much as it reflects better detection.”

Until they have a better count of the number of people infected, experts can’t calculate the coronavirus’s death rate. And since viruses are capable of mutating quickly, much of the information scientists have gathered may only be temporarily accurate.

“In any evolving outbreak, you need to make response decisions with imperfect information,” Katz said.

Mina said he has “absolute faith” in the CDC’s ability to stay on top of the situation. The health agency alerted doctors in early January to be on the lookout for patients who might have the virus, and last week it began screening passengers at U.S. airports that receive flights from Wuhan.

But the CDC isn’t running the show, and questions still abound about global preparedness. On Thursday, WHO officials said the outbreak did not rise to the level of “a global health emergency,” but that “it may yet become one.”

Dr. Guan Yi is almost certain that it will. Yi, an infectious disease expert at the University of Hong Kong, told reporters that even the drastic quarantine measures affecting 36 million people in and around Wuhan won’t be enough to keep the coronavirus from spreading because the Chinese government acted too late.

Yi also said he visited markets in Wuhan after the outbreak began and was dismayed by the lack of hygiene he observed there. Though he has put his expertise to use to fight SARS and several influenza outbreaks involving novel strains from birds and pigs, this is the first time he has felt hopeless, he said.

Indeed, Mina said some pathogens prove to outsmart even the world’s best public health agencies — and when they’ve never been seen before, they have a competitive advantage.

“Something as horrific as Ebola can seem better than this, because we’ve had years to understand it. At least we would really know the beast we’re up against,” he said. “As humans, we are always fearful of the unknown.”

Times staff writer Richard Read contributed to this report from Seattle.