Massive opioid case may end with huge settlement. Where would the money go?

- Share via

The largest civil trial in U.S. history is scheduled to begin in a matter of days, putting those who made, marketed, distributed and dispensed prescription painkillers under the legal spotlight. But those on the front lines of the opioid epidemic are already looking beyond the courtroom to the massive settlement they expect will ultimately resolve the case.

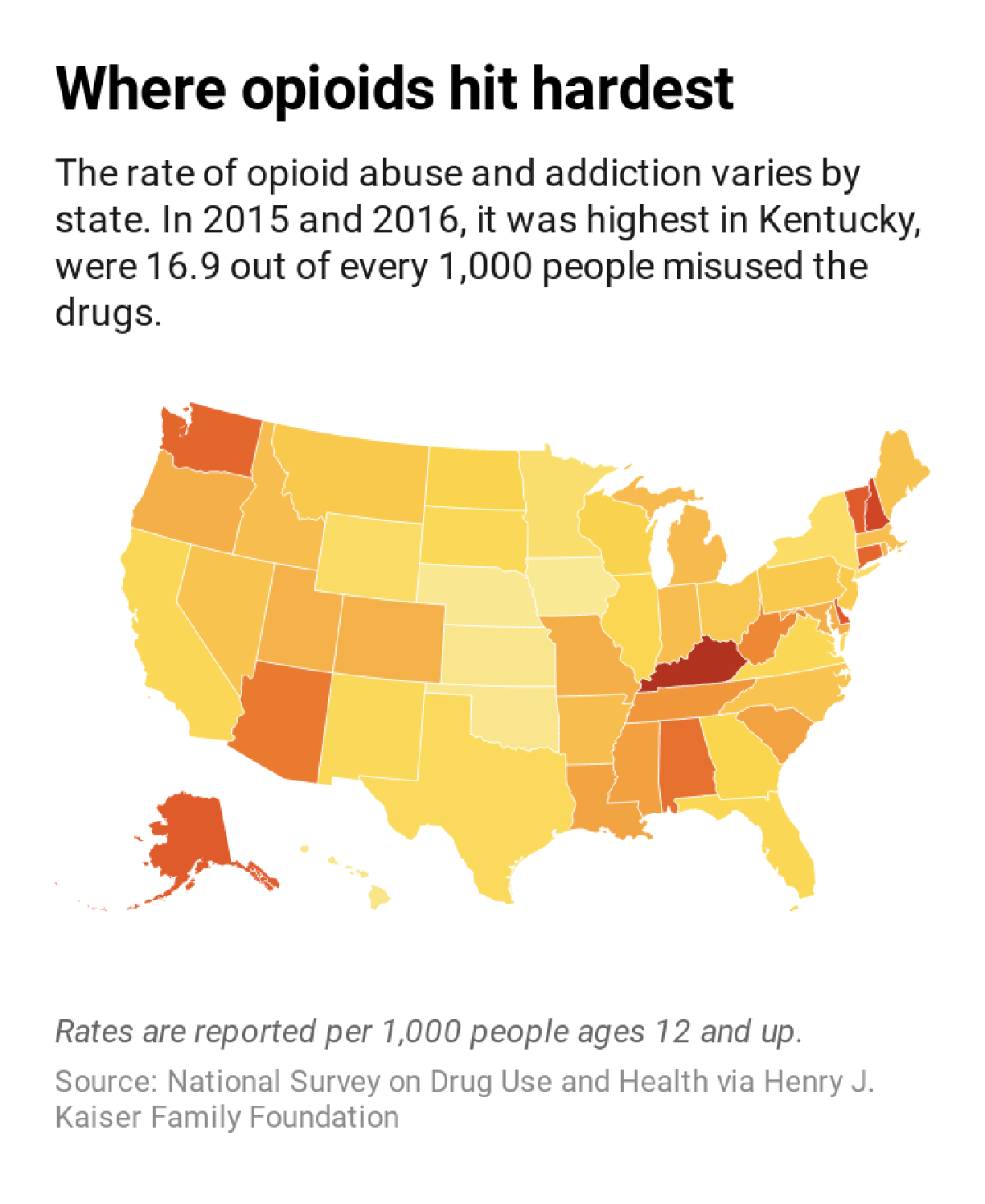

Experts have little doubt it would be the most complex payout the country has ever seen. It would exact so much, from so many companies. And it would need to do so much for so many people, starting with the 2 million Americans ensnared in addiction.

A settlement in the case known as Multidistrict Litigation 2804 would have many pricey pieces. The total cost could easily range upwards of $100 billion.

It would need to fund — potentially for years — counseling and addiction treatment for those ready to try it.

It would have to broaden access to the opioid-reversal drug naloxone and underwrite the development of newer, more effective rescue drugs, so that those who overdose have a chance to get clean.

It could pay for drug abuse prevention campaigns for the public, safe-prescribing seminars for doctors and abuse awareness programs for pharmacists.

It would probably include drug screening for pregnant women as well as treatment for infants exposed to opioids in the womb.

It might fund support groups for families of the addicted and grief services for those left behind.

It would reimburse state and local health departments for the money they’ve spent treating millions of victims.

That’s not even an exhaustive list. And, of course, there’s no amount of money that can bring back the 400,000 Americans who lost their lives to opioids.

A global settlement would require the consent of the roughly 35,000 plaintiffs in the case as well as the 348 pharmaceutical companies, mom-and-pop drugstores, professional medical associations and other assorted individuals they have accused of fueling an epidemic of death and dependence.

U.S. District Judge Dan Aaron Polster, who presides over the case from his Cleveland courtroom, has leaned hard on all sides to settle before jury selection begins Wednesday. That’s much easier said than done.

Who is to blame for the nation’s deadly opioid epidemic? That’s the question at the heart of MDL 2804, largest civil action in U.S. history.

To appreciate the magnitude of the challenge, consider the plan Oklahoma devised to address the opioid crisis within its borders. The state proposed an expansion of its opioid addiction treatment services, public awareness campaigns aimed at addiction prevention and proper medication disposal, and funding for programs aimed at treating pain with non-opioid therapies, among other elements.

The projected 20-year cost came to $17 billion — and that’s for a state with just 1% of the U.S. population and an opioid overdose death rate 30% lower than the national average.

“There are a million moving parts” to this case and its settlement, said University of Georgia litigation expert Elizabeth Burch. “And as soon as you figure it out, it changes on you.”

Complex as it is, the opioid case isn’t completely without precedent. Legal experts liken it to the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement in which seven tobacco companies agreed to pay U.S. states billions of dollars every year to compensate for decades’ worth of tobacco-related healthcare costs. Those payments total more than $126 billion so far — and they will continue in perpetuity, reaching a projected $246 billion by 2025. (The deal also included provisions that dramatically curtailed tobacco companies’ freedom to market and advertise their products.)

A settlement of MDL 2804 would probably be much smaller, experts agree. Even at the current pinnacle of the opioid crisis, tobacco use kills 10 times as many people in the U.S. every year. And the opioid epidemic has been brief compared with tobacco’s centuries-long hold.

Still, Big Tobacco’s humbling can serve not just as a model for an opioid settlement, but a cautionary tale as well. Free to spend the proceeds as they saw fit, several states used their windfalls to plug budget gaps and fund public works programs such as school and highway improvements.

In the fiscal year that ended Sept. 30, the states collected $27.3 billion from the settlement and tobacco taxes. But only $650 million will be spent on public health initiatives, such as programs to help people quit smoking or that prevent kids from starting in the first place, according to a tally by the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. That’s no match for the $9.5 billion the tobacco industry spends on U.S. marketing each year.

The biology of addiction makes this imbalance even worse. Most smokers need to quit at least eight times before they kick the habit for good, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Cancer Society. (One recent study said 30 quit attempts was a more realistic estimate.)

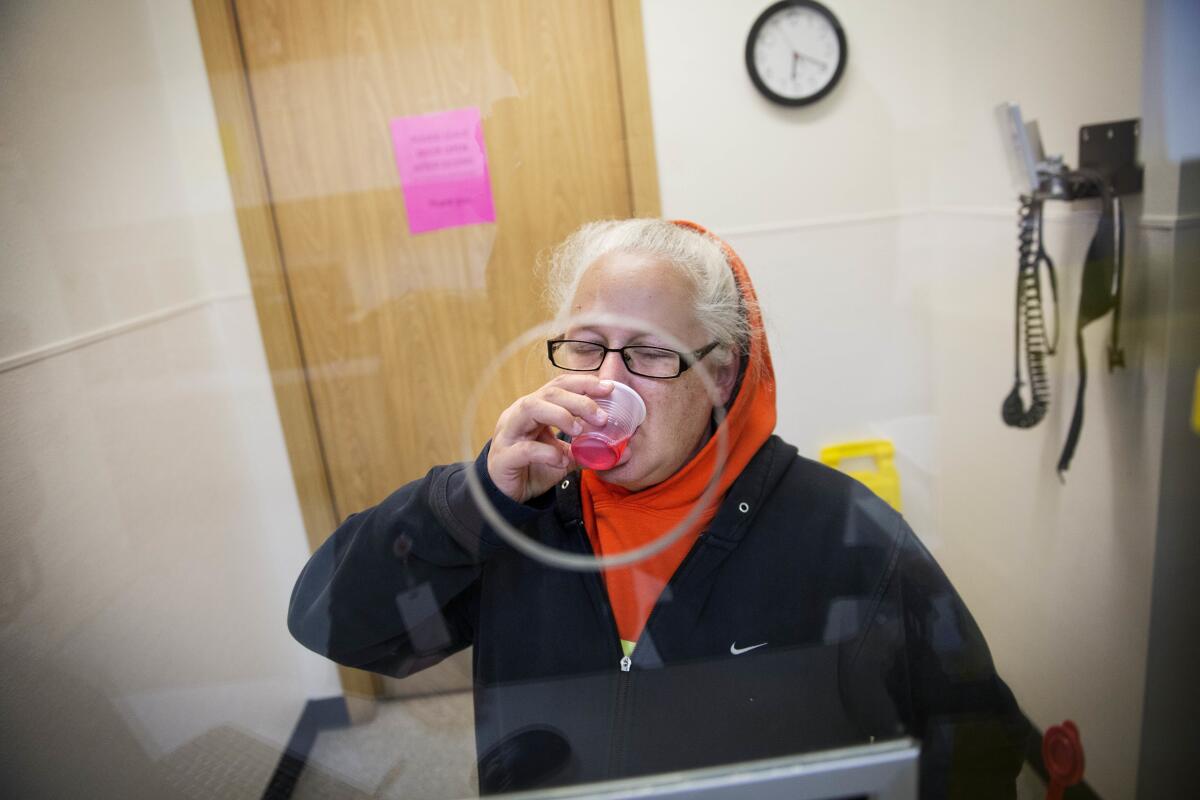

Getting people off opioids is unlikely to be any faster or easier, experts say. People with an addiction are typically slow to recognize their problem, and in any given year, only 2.1% of those who need treatment actually seek it out, according to a national survey by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Beyond that, addiction treatment often fails, even when using the most effective medications. The National Institute on Drug Abuse estimates that the relapse rate for drug users in recovery falls somewhere between 40% and 60%.

Getting everyone involved in the opioid case to agree on the price tag for a settlement will be challenging enough. Figuring out how to spend that money could take years.

Mike Moore, who helped broker the tobacco deal as Mississippi’s attorney general, said an opioid agreement must go beyond a single dollar figure and earmark funds for use in directly reversing the epidemic.

“If you just get virtually every city and county in the United States and give everyone a check, that’s great,” said Moore, who now represents several counties and cities in MDL 2804 and, separately, the states of Mississippi, Ohio, Louisiana, and Arkansas. “But then, what are they going to do about the opioid epidemic?”

Any settlement would probably be divvied up among the MDL 2804 plaintiffs based on three factors, according to Joe Rice, a lead attorney in the case: the volume of opioid painkillers sold within each city, county and state; the number of people in each jurisdiction who died of opioid-related overdoses; and the number in each place who reported an addiction to the pills.

As smaller settlements have been struck in Oklahoma and elsewhere, skirmishes have erupted over which governmental entities should get to decide how the money is used.

Many cities and counties are intent on using settlement funds to launch drug-prevention programs and build addiction treatment centers. Leaders of Cuyahoga County — one of two Ohio counties that settled early with some opioid drugmakers — unveiled a $23-million plan last week to expand residential drug treatment, hire field recovery support coaches and create an opioid treament program in its jail.

That leaves $14 million of settlement money up for grabs. Moore and others worry that after an initial flurry of spending on opioid treatment and prevention, the settlement’s beneficiaries will use what’s left to replenish coffers exhausted by the opioid crisis or divert the funds to other priorities.

“It’s my biggest fear,” he said.

Dr. Kathleen T. Brady, who chairs the executive committee of the International Society of Addiction Medicine, said it would be a “shame” if opioid settlement funds aren’t used to address the crisis. Her wish list includes rebuilding and expanding the workforce that delivers addiction services, funding research on pain and addiction, and training doctors in pain care and addiction treatment.

Few, if any, families who lost breadwinners, caregivers, doting grandparents or promising children would probably get a penny from an opioid settlement. People struggling with addiction won’t be compensated for lost jobs, shattered families or time spent in jail. And those paying for addiction treatment won’t be reimbursed for money they’ve turned over — often many times — in a bid to rescue a loved one from opioids.

That’s because any settlement funds would flow to the MDL 2804 plaintiffs or to the 49 states (all except Nebraska) that have joined forces to go after those they say are responsible for the opioid epidemic. Virtually all of those plaintiffs are governmental entities. In principle, they could decide to use settlement funds to repay families or individuals for their troubles. But that is something the tobacco settlement never did, and no one in the opioid case has entertained that possibility openly.

“Even if this is super successful, none of this litigation alleviates the burden on the end users,” Burch said. “This isn’t for them.”

How to spend the settlement money is likely to be a point of contention among politicians, state legislatures and counties for years to come, she said.

That would be a disaster, said Matthew Myers, president of the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids.

Unless prevention and treatment programs get an infusion of funds, people will keep using opioids and new patients will keep getting addicted, Myers said. And if settlement funds aren’t spent to address the epidemic, he added, “it lets the wrongdoers off the hook.”

Yale law professor Abbe Gluck sees the prospect of a global settlement in MDL 2804 differently.

The overwhelming likelihood that a trial will never happen — that dirty laundry will not be aired and righteous anger will not be vented in public — may seem like a loss, Gluck said. But a settlement may be the best means of serving a higher public purpose.

The opioid epidemic needs money and it needs fixes, she said. And with half a million Americans projected to die of opioids over the next decade, it needs both things fast.

Given the number of lawsuits and plaintiffs in play, Gluck said, “it’s the only way to get relief in anyone’s lifetime. It’s just more practical.”