With Obamacare, fewer Americans were uninsured when they were told they had cancer

- Share via

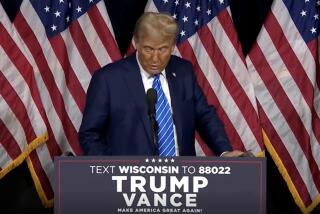

As President Trump and his allies in Congress keep pushing to get rid of Obamacare, new research shows that the contentious law has succeeded in expanding health insurance coverage for Americans with cancer.

But not everywhere. This upside of Obamacare — known formally as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, or ACA — was seen primarily in states that participated in the Medicaid expansion that the law made possible.

For the record:

11:00 p.m. Oct. 19, 2017A previous version of this story made a few incorrect references to Medicare. It should have said Medicaid.

By comparing states that expanded Medicaid to states that didn’t, the researchers determined that the law reduced by about half the percentage of patients who did not have health insurance when they were diagnosed with cancer.

The findings, published Thursday in the journal JAMA Oncology, are based on five years of data from 13 states collected by the National Cancer Institute. The states in the NCI registry have a demographic profile that mirrors that of the country as a whole, and the cancer patients who are tracked are between the ages of 19 and 64.

Overall, the situation in the years 2010 to 2013 looked markedly different from the situation in 2014, the first year that Obamacare and the Medicaid expansion went into effect.

In the pre-Obamacare years, 5.73% of the patients who were newly diagnosed with cancer did not have health insurance to help them pay for their treatment, the researchers found. In 2014, that figure dropped by one-third, to 3.81%.

The percentage of uninsured patients fell for each type of cancer reported. Among patients who were told they had breast cancer, the proportion that lacked health insurance fell 26% in the first year of the Obamacare era. For patients with prostate cancer, the figure was 29%. It was just under 33% for those diagnosed with lung, bronchial or thyroid cancer.

When looking at cancers by stage at diagnosis, the law’s benefits were spread pretty evenly among patients diagnosed with local, regional or metastatic disease that had spread to distant organs. In all three cases, the percentage of patients without health insurance fell by 33% to nearly 35%.

After the law went into effect, new cancer patients of all races and ethnicities were less likely to be uninsured. Among whites, the percentage without health insurance fell by 37%, compared with an 18% reduction for blacks. Among Latinos, the percentage of uninsured patients dropped by 40%. Declines were similar in counties with more poverty (33%) and those with less poverty (36%).

The biggest differences were between the states that chose to expand their Medicaid programs (California [where it’s called Medi-Cal], Connecticut, Hawaii, Iowa, Kentucky, Michigan, New Mexico, New Jersey and Washington) and those that didn’t (Alaska, Georgia, Louisiana and Utah).

Even before 2014, cancer patients in the nine states that expanded Medicaid were less likely to be uninsured at the time of their diagnosis. In 2013, for instance, 5% of these patients lacked health insurance when they were told they had cancer, a figure that dropped to 2.5% the following year. Meanwhile, in the four states that didn’t expand Medicaid, the percentage who were uninsured when they were diagnosed rose from 8.4% in 2013 to 8.8% in 2014 (an increase that wasn’t large enough to be statistically significant).

The researchers used the non-expansion states as a proxy for what would have happened nationwide if Obamacare had never become law. After accounting for demographic and other differences in the two groups of states, they calculated that the law’s passage reduced the percentage of uninsured first-time cancer patients by 2.38 points — or just about half.

The study makes no predictions about what would happen to these cancer patients if the Republicans promising to “repeal and replace” Obamacare succeed in that goal. But the gains seen in the study might not necessarily be erased, said study leader Aparna Soni.

Perhaps the patients who got insurance through Medicaid now see its value and would be more likely to pay for it themselves even if their subsidies went away, said Soni, a doctoral candidate in economics and public policy at Indiana University in Bloomington.

However, it’s also possible that insurance rates may fall below 2013 levels if new kinds of low-skilled jobs are less likely to come with health insurance benefits, she said.

Follow me on Twitter @LATkarenkaplan and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE

Scientists engineer proteins that caused obese animals to lose weight and lower cholesterol

Doctors urged to make a public commitment to talk to their patients about guns and gun safety

How guilt, anxiety and distress may help fight cancer