NIH says it will retire all remaining research chimpanzees

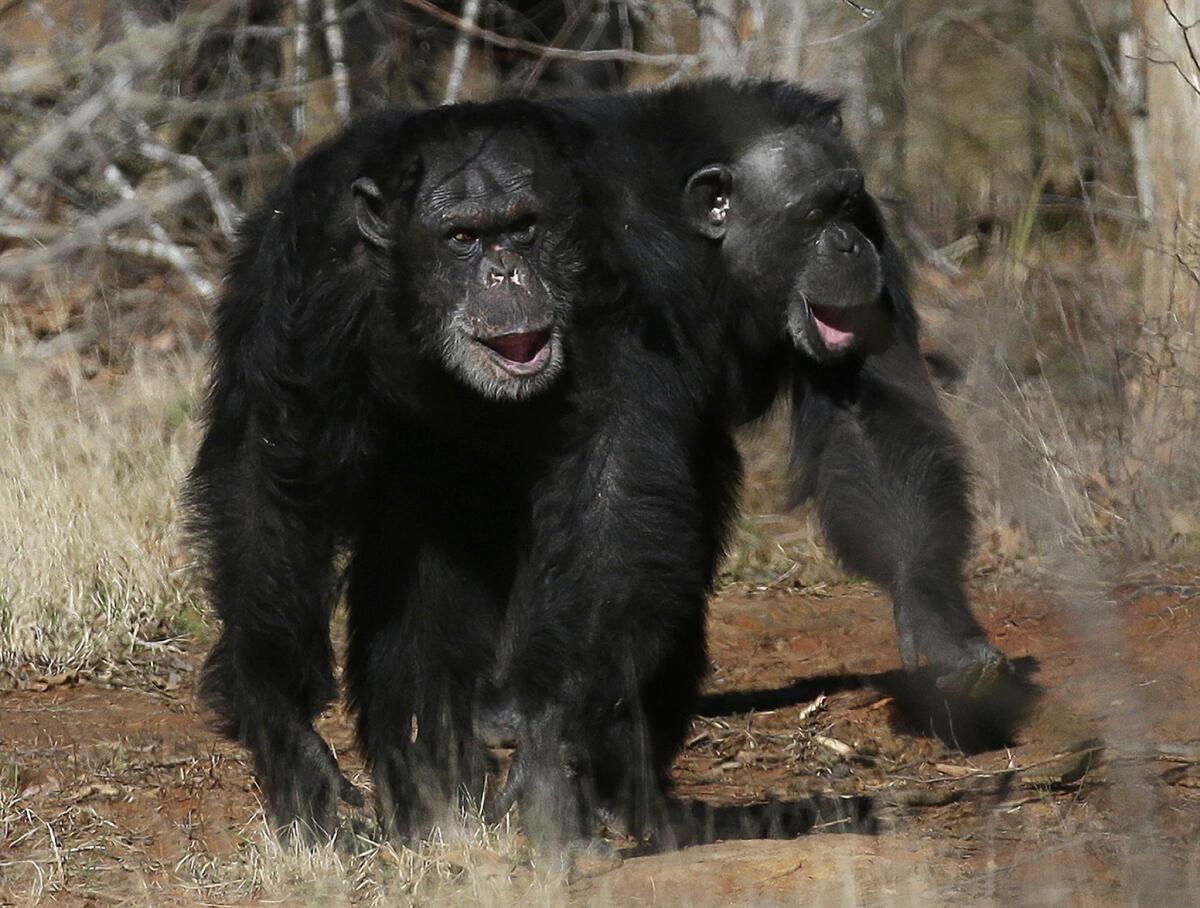

Two chimps at Chimp Haven in Louisiana. Fifty soon-to-be-retired research chimpanzees from the National Institutes of Health will be joining them, Dr. Francis Collins announced.

- Share via

The National Institutes of Health will reduce its staff by 50 — chimpanzees.

The director of the nation’s biomedical research facility announced late Wednesday that the primates, the closest living relatives to humans, would no longer be needed to test experimental vaccines, drugs or other treatments. As a result, the remaining animals in the NIH’s chimp colony will be sent to sanctuaries to retire.

“It is clear that we’ve reached a tipping point,” Dr. Francis Collins explained in an open letter. “Effective immediately, NIH will no longer maintain a colony of 50 chimpanzees for future research.”

The decision, hailed by animal rights activists, was a long time coming. In 2010, the NIH said it had asked the Institute of Medicine to evaluate the agency’s need for chimpanzees to conduct “biomedical or behavioral research that will be needed for the advancement of the public’s health.”

The resulting report, issued in 2011, concluded that most research involving chimps at that time was unnecessary. Studies with the animals could continue only in cases in which strict criteria were met, including:

* There were no alternative animals or other biological models that could be used to study a disease.

* It would be unethical to use humans in place of chimps.

* A decision to forgo tests involving chimps would significantly slow or halt the development of treatments to prevent, control or care for “life-threatening or debilitation conditions.”

* If any research projects met the criteria, they would have to be conducted in a way that “minimizes pain and distress.”

See the most-read stories in Science this hour >>

The NIH implemented these recommendations in June 2013, sending about 300 chimps into retirement.

The IOM report noted that chimpanzees could be valuable to scientists working on therapies for hepatitis C or using monoclonal antibodies to treat cancer and autoimmune diseases. However, no new projects have come along that have received approval under the new criteria, Collins noted. In part, that’s because researchers have been able to genetically modify animals like mice and rats so that they were better stand-ins for people.

Perhaps the final straw was the decision in June by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to classify captive chimpanzees as endangered. That means anyone who might bring harm to a captive chimp — a description that covers any medical researcher — would have to get a special permit to do so. “We are not aware of any permits that have been sought for this purpose,” Collins wrote.

With all this in mind, Collins made the decision to send the NIH’s remaining research chimpanzees to Chimp Haven, the 200-acre federal sanctuary in Louisiana. The facility is currently home to more than 200 chimps, and there will be a wait list for some of the new additions.

Relocations will take place “as space is available and on a timescale that will allow for optimal transition of each individual chimpanzee with careful consideration of their welfare, including their health and social grouping,” Collins wrote.

The Humane Society of the United States is among the animal rights groups that has long pressed for the chimps’ retirement. On Wednesday, the society’s leader called the decision “thrilling.”

“We really see the agency closing and locking the door behind the chimps and throwing away the key on their way out of the laboratories,” Wayne Pacelle, president and chief executive of the Humane Society, said in a blog post. “We applaud NIH director Francis Collins for his foresight in taking this action.”

The retirements won’t mean that researchers will be limited to rodents, fruit flies and worms. “Research with other non-human primates will continue to be valued, supported, and conducted by the NIH,” Collins wrote.

Follow me on Twitter @LATkarenkaplan and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

ALSO

Divorced couple’s frozen embryos must be discarded, judge rules

Charlie Sheen becomes the new face of HIV as awareness of the disease wanes

Scientists spy two -- or maybe three -- planets in the process of being born