3.2 million years after her death, autopsy reveals Lucy probably died after falling from a tree

- Share via

It’s the coldest case in science, and it may have just been cracked.

Forty years after researchers discovered Lucy, an early human ancestor who lived 3.2 million years ago, scientists think they now know how she died.

After examining high-resolution CT scans of broken bones in Lucy’s right shoulder, as well as the damage to other parts of her skeleton, researchers at the University of Texas at Austin propose that the small hominid’s life ended shortly after a catastrophic fall from a great height — probably from a tree.

“What we see is a pattern of fractures that are well documented in cases of people who have suffered a severe fall,” said John Kappelman, a UT professor of anthropology and geological sciences. “This wouldn’t happen if you just fell over.”

In a paper published Monday in Nature, Kappelman and his colleagues suggest that Lucy tumbled out of a tree, landed hard on her feet and then pitched forward, extending her arms straight out in front of her in a desperate attempt to break her fall.

The force of the impact of her hands hitting the ground is likely responsible for the debilitating compression fracture in her shoulder, the authors write. But the fall also caused several bones in her body to break and probably lead to severe organ damage. Death would have followed swiftly.

If their hypothesis is correct, Lucy was likely conscious in the last few moments before she died.

“She did exactly what we would do,” Kappelman said. “She was trying to save her life.”

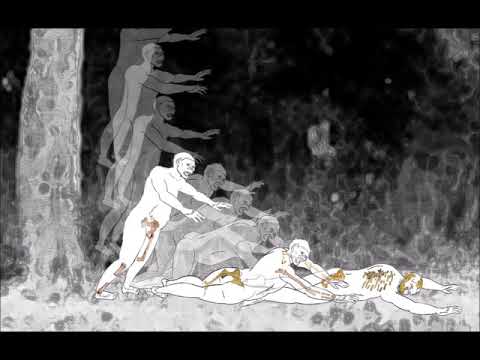

Animation simulates how Lucy may have died after a fall from a tall tree.

Lucy was discovered in 1974 by paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson in the Hadar area of central Ethiopia. Johanson and his colleagues named the fossil after the Beatles song “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” because it was playing over and over again at their camp the night she was found.

Part of what made the Lucy find so important was her unusual mix of features. She had relatively short legs and long arms like a chimpanzee, but her wide pelvis indicated that she walked upright. This combination of traits suggests her species, Australopithecus afarensis, may have been a link between modern humans and our tree-living ancestors.

Lucy was much smaller than modern humans. Although she was probably a full-grown adult at the time of her death, she stood just 3 feet 6 inches tall, and weighed about 60 pounds — about the size of a first-grader.

Her fossilized remains have been studied by dozens of scientists, but this is the first study to hypothesize how she met her end. Kappelman said that’s because for the most part, ancient bones do not reveal how an animal died.

“Despite what you see on shows like ‘CSI,’ skeletons only rarely preserve evidence of death,” he said. “If we didn’t see those arms sticking out, the argument we make might not be so powerful.”

Kappelman’s research into Lucy’s demise began in 2008, when the Ethiopian government granted him 10 days to scan the preserved parts of her skeleton at the high-resolution CT lab at the University of Texas.

Previous attempts to peer into the interior of Lucy’s bones in the late 1970s had failed because CT scanners at that time were not powerful enough.

“Lucy is a fully mineralized fossil, so she’s like a rock, and the problem with lower energy CT is that they can’t see through rock” Kappelman said. “Up until 2008, we had had no data at all on the internal structure of her bones. She was radiographically opaque.”

It was while he was scanning her right humerus, the upper arm bone, that Kappelman realized the fractures on the end of the bone closest to the shoulder were unlike anything he’d seen in other fossils.

Ancient fossils often break apart due to geological forces. For example, breaks could be caused by the tremendous pressure of rock that can build up on fossils over time. They can also fracture when shifts in the Earth’s crust tear them apart. But Kappelman thought the fissures in Lucy’s bones might have a different origin. Perhaps they they were due to an injury instead.

To check his hunch, he called Dr. Stephen Pearce, a friend of a friend and an orthopedic surgeon at the Austin Bone and Joint Clinic. Pearce agreed to take a look at a cast of Lucy’s right humerus bone in his medical office.

“It looked very distinctly like a proximal fracture we see pretty routinely as orthopedists, usually because of a fall off a ladder or scaffolding, or a car crash,” Pearce said. “I’m not an anthropologist, but it certainly looked like the fracture pattern you would see if she fell out of a tree.”

Over time, Kappelman showed his cast of the humerus to eight different orthopedic surgeons. All of them said it looked like a four-part proximal humerus fracture that occurs when a person puts out their hands to break a fall.

“It wasn’t like they were saying, ‘It might be this or it could be something else,’” Kappelman said. “It was not even a question from their perspective.”

But how could the researchers know that the event that caused the bone fractures also caused her death?

Kappelman and his co-authors argue that the fall could not have occurred much before Lucy died because the bone breaks were clean and showed no sign of healing.

They also say the injury could not have happened long after death because tiny slivers of bone that broke off in the impact remained in their post-injury position rather than scattering all over the ground. This could only happen if the fibrous tissue that forms a type of skin around the bone had not yet decayed, the authors said.

“Kappelman’s point is that these slivers of bone can only be accounted for if the fibrous tissue was still there, holding everything in place,” said Jack Stern, an anatomist and professor emeritus at Stony Brook University in New York who was not involved in the work. “That argument impressed me.”

In addition, the authors describe a series of other devastating fractures in Lucy’s left shoulder, right ankle, left knee, pelvis and first rib that are consistent with their great fall hypothesis.

But not everyone is buying the argument.

Donald Johanson, director of the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University and the man who discovered Lucy more than 40 years ago, said the paper does not provide convincing evidence for how Lucy died.

“Tens of thousands of fossils have been recovered by numerous paleontologists and they all show the same kind of bone breakage interpreted by me and my team to be due to geological forces,” he said. “Once these bones get interred in the water, sandstone starts building up on top of them and it’s a lot of pressure. These forces cause these kind of fractures.”

According to Johanson, we will probably never know how Lucy died.

William Jungers, an anthropologist at Stony Brook who reviewed the paper for Nature, said he also had “severe doubts” about the possibility of diagnosing the cause of death in a fossil as old as Lucy. However, Kappelman’s argument won him over.

“Virtually every major reservation I had was anticipated or addressed head-on in the review process,” he said. “The detailed, comprehensive analysis of her fracture pattern compared to the extensive human clinical literature on skeletal trauma resulting from a rapid ‘vertical deceleration event’ is especially compelling to me.”

Although “paleo-forensics” doesn’t allow for replication experiments, John Fleagle, an evolutionary biologist at Stony Brook who was not involved in the work, said there may be ways to test Kappelman’s hypothesis.

“If the bones of antelopes, warthogs and lions show similar bone breakage, it probably wouldn’t be due to a fall from a great height,” he said. “I look forward to seeing such a study.”

Kappelman said he’s working on it.

“My co-author Dr. Todd and I are currently working up the fossils from Trinil in Java, the site where Homo erectus was first discovered in the 1890s. There are many thousands upon thousands of fossil mammals [including Homo erectus] at this site,” he said. “Spoiler alert: Not a single one of these thousands of fossils show any fractures similar to the compressive fractures preserved in Lucy’s skeleton.”

In the meantime, people with access to a 3-D printer can evaluate the findings presented in the paper for themselves.

The Ethiopian National Museum has made a set of 3-D files of Lucy’s shoulder and knee available online at eLucy.org that will let users replicate Lucy’s bones in the comfort of their homes and classrooms.

Kappelman said he is looking forward to getting feedback on his findings.

“What we presented is a scientific hypothesis, but it doesn’t mean we’re right,” he said. “This is the most famous fossil in the world. I’m curious to hear what other people say about it.”

Do you love science? I do! Follow me @DeborahNetburn and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE

Meet Octobot, a soft-bodied robot that moves like an octopus

Your coffee habit may be written in your DNA

The aging paradox: The older we get, the happier we are