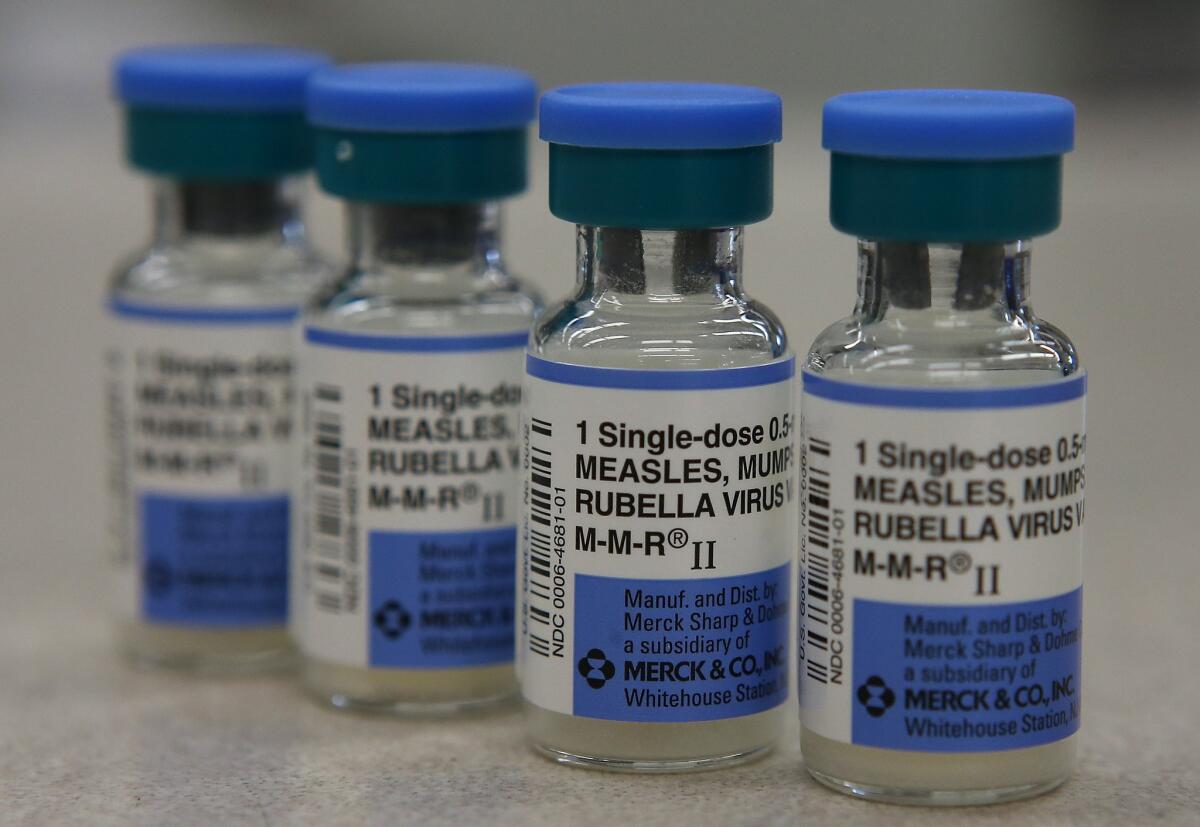

Study rules out link between autism and MMR vaccine even in at-risk kids

The younger siblings of those diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder are at higher than usual risk of developing the disorder. So researchers looked at whether getting the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine increased autism incidence in such children. It didn’t.

- Share via

At least a dozen major studies have found that early childhood vaccines do not cause autism. But one possibility remained: that immunizations could cause autism in a small group of children who were already primed to develop the disorder.

Now, new research has ruled out that possibility too.

A study of nearly 100,000 children found that toddlers known to have an elevated risk of autism were no more likely to be diagnosed with the disorder if they were vaccinated against measles, mumps and rubella than if they weren’t. What’s more, the diagnosis rate for high-risk children who were vaccinated was the same as for immunized children with no family history of the disorder, according to the report published Tuesday in the Journal of the American Medical Assn.

By hunting for — and failing to find — a link between the MMR vaccine and autism spectrum disorders, or ASD, in children with an older sibling who had the disease, the study leaves no doubt that the two are not connected, experts said.

While “abundant” evidence demonstrates that the MMR vaccine does not lead to ASD in the general population, it was still worth investigating whether there might be a connection among the more vulnerable population of kids with an older sibling on the autism spectrum, said Dr. Bryan H. King, an autism specialist at Seattle Children’s Hospital who was not involved in the new research.

“Could it be that if all the requisite genetic and other risks are present, MMR can lead to the development of autism?” King asked in an editorial published alongside the JAMA study. “If so, the population in which there might be such a signal would be families already affected by autism.”

By showing such fears to be unfounded, the study — and others before it — makes plain that “the age of onset of ASD does not differ between vaccinated and unvaccinated children, the severity or course of ASD does not differ between vaccinated and unvaccinated children, and now the risk of ASD recurrence in families does not differ between vaccinated and unvaccinated children,” he said.

But the vocal minority of parents who contend that there is a cause-and-effect relationship between the MMR vaccine and autism aren’t likely to be swayed, said Dr. James Cherry, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at UCLA who wasn’t involved in the new research.

“Eight million studies are not going to convince people,” he said.

Autism is a neurological disorder that has become more common in recent years, though scientists don’t know why. In 2002, ASD affected about 1 in 150 children in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; by 2010, the prevalence had risen to about 1 in 68.

Symptoms can be relatively mild, as in the social difficulties of people with Asperger’s syndrome, or they can be so debilitating that individuals, as adults, can’t live on their own.

The idea that vaccines cause autism goes back to a 1998 study in the medical journal Lancet that described 12 young children with autism-like symptoms. Eight of those children started having behavioral problems after they got the MMR vaccine, according to their parents.

That study was retracted in 2010 after its lead author, Dr. Andrew Wakefield, was found to have falsified his research. Yet his claims continue to stoke the anti-vaccination movement.

Epidemiologists say low immunization rates fueled the measles outbreak that began at Disneyland in December and sickened at least 157 people in the United States, Canada and Mexico. The outbreak prompted lawmakers in California and elsewhere to try to close loopholes that give parents wide latitude to refuse vaccinations for their children.

Last week, protests by hundreds of parents derailed — at least temporarily — a measure making its way through the California Senate’s Health Committee that would have required vaccination of virtually all children as a condition for attending public and private schools. Public health officials in the state say low vaccination rates, especially in five geographical clusters, are almost certain to spur new outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.

For the JAMA study, Dr. Anjali Jain, a pediatrician and health policy expert at the Lewin Group in Falls Church, Va., and her colleagues mined the records of 95,727 children born into families covered by a large commercial health plan to see whether they could find any link between vaccination and an autism diagnosis. All of the children had at least one older sibling, including 1,929 who had been diagnosed with ASD.

When an elder sibling has autism, the risk for younger siblings is known to be increased. So if there is a weak association between the MMR vaccine and autism, it would show up clearly in this “risk-enhanced population,” the study authors reasoned.

It did not. Indeed, a first pass at the statistics seemed to suggest that getting the MMR vaccine conferred some protection against development of ASD.

But the researchers discounted that likelihood. Instead, they wrote, the lower rates of autism among those who were vaccinated probably reflected the fact that parents often defer vaccination when a child shows early social or communications delays.

The findings should reassure parents that even if they have a child with ASD, it is safe to vaccinate his or her siblings, King wrote.

At the same time, the results help “move the field forward toward a more focused and productive search for more temporal and environmental factors that contribute to autism risk,” he wrote.

Over the last decade, the search for autism’s causes have shifted definitively away from the infant and toddler years and focused increasingly on factors at play “mostly in utero and even before,” said Margaret Daniele Fallin, director of the Wendy Klag Center for Autism and Developmental Disabilities at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Fallin was part of a team that studied the sperm of men whose children had early signs of autism. They found a distinct pattern in the “epigenetic tags” that help regulate the activity of genes, especially those that play a role in brain development, according to results published last week in the International Journal of Epidemiology.

Another study published last week in JAMA found that babies born to mothers who had Type 2 diabetes before becoming pregnant were about 20% more likely to develop autism than those who did not. Babies of mothers who developed gestational diabetes before 26 weeks of pregnancy — but not later — were at even higher risk of developing ASD. These findings suggest that exposure to metabolic abnormalities during a crucial period of fetal brain development may play a role in the disorder.

Twitter: @LATMelissaHealy