Cholesterol and Alzheimerâs disease link strengthens in study

Well before signs of dementia trigger a diagnosis of Alzheimerâs disease, a personâs cholesterol levels may be a bellwether of amyloid plaque build-up in the brain, a new study finds. Long considered a reliable predictor of heart attacks and strokes, worrisome cholesterol levels may now raise concerns about dementia risk as well, prompting more aggressive use of drugs, including statins, that alter cholesterol levels.

The current study does ânot convincingly exclude the possibilityâ that taking statins might lower amyloid deposition, the researchers said. But neither did it show that those taking cholesterol medication were less likely to have the sticky plaques that gum up brain function. Only a larger study that gathers more of subjectsâ past health history can determine what role cholesterol-lowering medication might play in protecting against Alzheimerâs disease, the authors wrote.

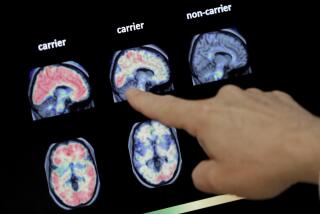

Published Monday in the journal JAMA Neurology, the latest research used PET Imaging to conduct a one-time âsnapshotâ of the brains of 74 older patients without dementia. They looked specifically to gauge the presence and concentration of amyloid plaques in brain regions most prone to early signs of the abnormal protein build-up: the frontal cortex, lateral parietal cortex, lateral temporal cortex, posterior cingulate and precuneus.

Past research has found higher levels of amyloid deposits in the post-mortem brains of people who had worrisome cholesterol readings before their death. But this is the first to find that beta-amyloid proteins may accumulate steadily in those living with higher cholesterol, possibly resulting -- should one live long enough--in dementia symptoms.

Among the subjects, with an average age of 78, having high levels of LDL-C âbadâ cholesterol was closely linked to having more amyloid plaque deposits in those regions. On average, those with low levels of HDL cholesterol--the âgoodâ cholesterol that at high levels is protective against cardiovascular disease--also had more amyloid plaque in their brains.

The researchers, from UC Berkeley, UC Davis and USC, found that other measures that physicians use to gauge a patientâs risk of heart attack or stroke--triglycerides and total cholesterol--had no clear relationship to amyloid plaques in the brain.

While none of the subjects in the study had been diagnosed with dementia, more than half suffered mild cognitive impairment--a decline in mental performance that sometimes progresses to Alzheimerâs disease. Three had been diagnosed with mild dementia.

As a group, the studyâs subjects had been aggressively treated for high cholesterol, however. Their average cholesterol levels were within the optimum range set by the American Heart Assn. (until recently published guidelines minimized the importance of such guideposts). Because researchers had only a one-time snapshot of subjectsâ cholesterol levels as well, they were unable to discern whether lowering cholesterol with medication resulted in fewer amyloid deposits.

How cholesterol levels could affect the formation of amyloid plaques in the brain is something of a mystery. Roughly a quarter of the cholesterol in our bodies resides in our brains. Cholesterol levels there seem to affect the synthesis of beta-amyloid proteins, their clearance from the brain, and their toxicity once plaques are established.

But the central nervous systemâs cholesterol is virtually walled off from that circulating throughout the rest of the body by the blood-brain barrier. So the link between circulating cholesterol levels and amyloid plaques in the brain is unknown. One possibility, recently suggested by research: oxysterols, oxidized derivatives of cholesterol that pass through the blood-brain barrier and may affect cholesterol levels throughout the body.

ALSO:

Beta blockers may reduce Alzheimerâs risk, study finds