Coronavirus Today: How to make a dream vaccine

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, Feb. 21. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

It’s hard to escape the feeling that after three difficult years, humanity has got COVID-19 handled. Sure, the coronavirus is still spreading, but for most of us, the prospect of catching it no longer fills us with dread. Now we can relax and shift our focus elsewhere.

Not so fast, scientists warn.

This pandemic has gifted us a chance to catch our collective breath, and we should use the time wisely by getting ready for the next one, they say.

Actually, their real goal is to prevent another coronavirus-fueled pandemic from happening. The 21st century has already seen three deadly outbreaks caused by coronaviruses, and that’s quite enough for them.

First there was the 2003 epidemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, which killed 774 people, mostly in China and Hong Kong. Then there was Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, or MERS, which emerged in Saudi Arabia in 2012 and was responsible for at least 858 deaths. The most recent, of course, is COVID-19, whose global death toll now exceeds 6.8 million.

In the first two cases, and almost certainly the third, the coronavirus culprit jumped from an animal to a human. Considering that there are thousands of coronaviruses circulating in animals — bat species alone are thought to harbor more than 3,200 distinct coronaviruses — it’s a pretty safe bet that at least one will try to cross the species barrier in the foreseeable future.

The single most useful tool to thwart that scenario is a vaccine.

The ideal vaccine would be capable of neutralizing any kind of coronavirus that comes our way. It wouldn’t just keep people alive and out of hospitals, it would make sure they didn’t become sick in the first place. In doing so, it would preclude any upstart coronavirus from spreading among humans. And to top it all off, the protection afforded by this dream vaccine would last for years, perhaps even a lifetime.

Unfortunately, no such vaccine currently exists. But if we gave enough researchers enough resources to tackle the problem, it could.

It’s a tall order for sure, but an international team of more than 50 scientists has developed a road map for making it happen. The plan breaks down the problem into dozens of discrete pieces, identifying the individual hurdles that must be overcome and setting target dates for clearing them.

The experts who worked on the road map for nearly a year organized their epic to-do list around five topic areas:

Virology: In order to create a pan-coronavirus vaccine, scientists will need to get a better handle on all of the coronaviruses that are out there, and what they’re doing. Then they’ll need to figure out which ones are most threatening and how many will need to be factored into a vaccine design to ensure it is broadly effective.

Immunology: This means learning more about how different parts of the human immune system respond to coronaviruses — and once their protections kick in, how long they last. One thing scientists are keen to understand is how pre-existing immunity to one or more coronaviruses affects the way the immune system reacts when it encounters a brand-new member of the viral family.

Vaccinology: This involves figuring out what types of vaccines are capable of delivering the kind of protection our immune systems will need, as well as developing effective strategies to test vaccine candidates. Another consideration is making sure any successful vaccine can be manufactured and distributed worldwide.

Animal and human infection models: There’s no way to create a new vaccine without testing it first. That job starts in animals, so it will be crucial to find ones that react to viruses and vaccines the way people do. Unfortunately, different coronaviruses will likely require different animal models. When it’s time to test vaccines in people, they’ll need to have a careful way of doing it that exposes volunteers to the minimum amount of risk.

Policy and financing: In the early days of the pandemic, governments and other funders were willing to throw billions of dollars into developing a COVID-19 vaccine. Creating a vaccine that’s capable of knocking out a broad array of coronaviruses will require at least as much money, along with the political will to spend it.

That last topic is the least science-y, but in many ways it’s the most important, said Michael Osterholm, director of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, which released the 92-page road map today.

“If we don’t have the policy and financing, then we’re never going to have the research dollars invested to look into the virology, immunology and vaccinology,” he told me.

“This is not likely to be the last coronavirus pandemic,” Osterholm said. “In fact, this might not even be the big one.” He described a nightmare scenario involving a coronavirus that spreads as easily as the one that causes COVID-19 but has the 10% fatality rate of SARS or the 35% fatality rate of MERS.

With so much work to do, he and others who worked on the road map stressed the importance of getting started right away.

Can they get it all done?

“I don’t know,” he said, “but because I am a grandfather with five grandchildren, I will never waste one moment not trying.”

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 12:16 p.m. on Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Tackling trauma through dance

Mokhtar Ferbrache was incarcerated at the California Rehabilitation Center in Norco when the coronavirus arrived. The feelings of uncertainty, foreboding and dread that characterized those early months of the pandemic were magnified for those confined in prison.

“The whole time you’re sitting in there and you’re watching it move in the space,” Ferbrache told my colleague Steven Vargas. “It’s really weird, like a wave. You could see it moving and you’d see, ‘Oh, this person got it.’ And then you watch the people that were around him.”

He had no idea what the virus would do to a human body. All he knew was that when a fellow inmate caught it, he’d be moved into isolation with others who were infected.

So when Ferbrache tested positive himself on Christmas Day 2020, the news was accompanied by a strange sense of relief. The questions in his head would be answered — and he saw that COVID-19 was no joke.

At least 260 people in California prisons have died of COVID-19, according to the state Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Ferbrache recovered. But it wasn’t until much later that he came to appreciate just how traumatic the whole experience had been.

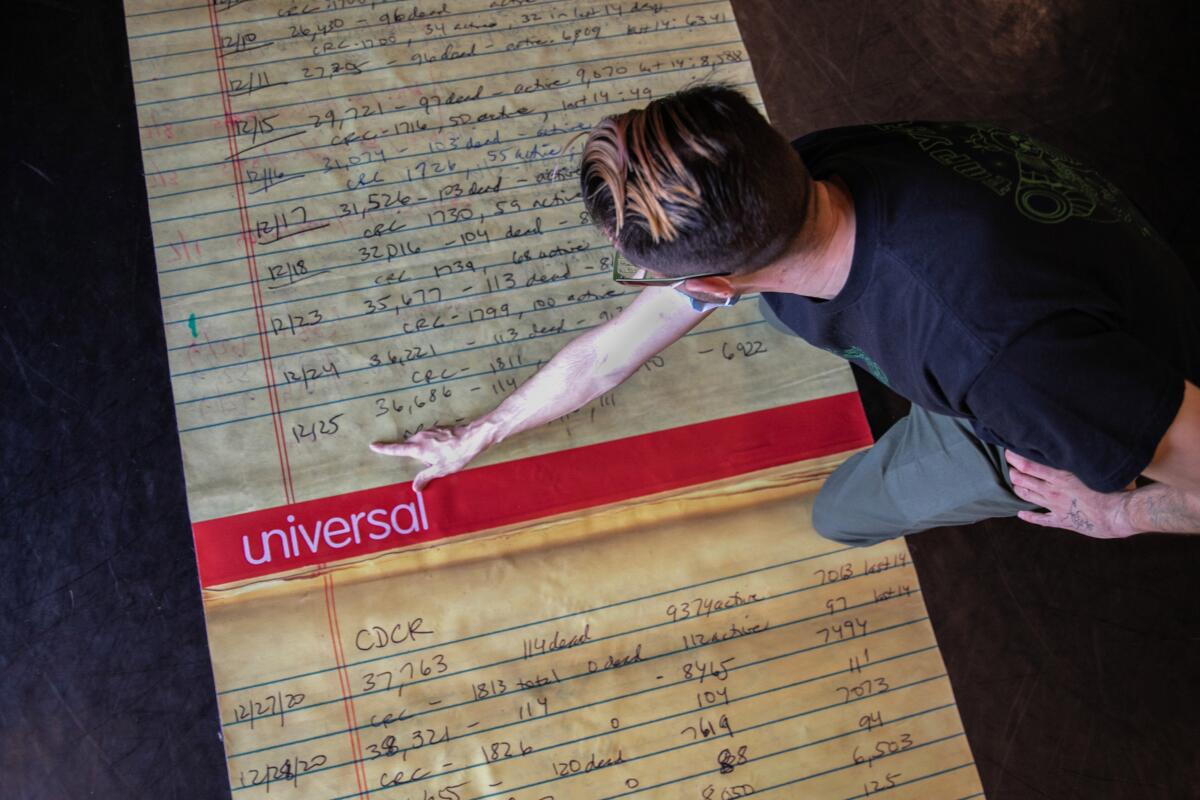

What brought his emotions to the surface was “Data or 7 Ways to Dance a Dance Through Prison Walls,” a show based on statistics about COVID-19’s effect on those inside California prisons. It was performed this month at the Odyssey Theatre in West Los Angeles.

In one of the numbers, long paper scrolls unfurled from the ceiling. Written across them were running tallies of the number of infections and deaths among the state’s incarcerated population.

Ferbrache was struck when he saw the date 12/25/2020. That’s when he became a COVID-19 statistic.

“It’s me,” he said when he saw it.

Audiences have had a similar reaction, he added: “It’s just writing on a piece of paper, but then to have it elicit such a response is so interesting to me.”

“Data” was brought to life by Suchi Branfman, who taught dance workshops at the California Rehabilitation Center for 10 years. The pandemic forced her to communicate with her students by writing prompts on pieces of paper. Dancers wrote back with words and drawings to convey their choreography ideas.

The show’s theme is that what happens in the prison industrial complex affects those of us on the outside as well as the people inside.

“How do we create work that invites people into understanding that we’re not separate from folks who are incarcerated, that we are implicated in their incarceration?” Branfman asks. “Our hope is that this is a place for us to situate a conversation through dance.”

A formerly incarcerated man who participated in the dance program said he hopes for something else as well — recognition from audiences that the dismal COVID-19 numbers represent real people.

“We’re human,” said the man, who requested anonymity to avoid risking his parole and safety. “Yeah, we did wrong, but we’re paying for it. We’re human.”

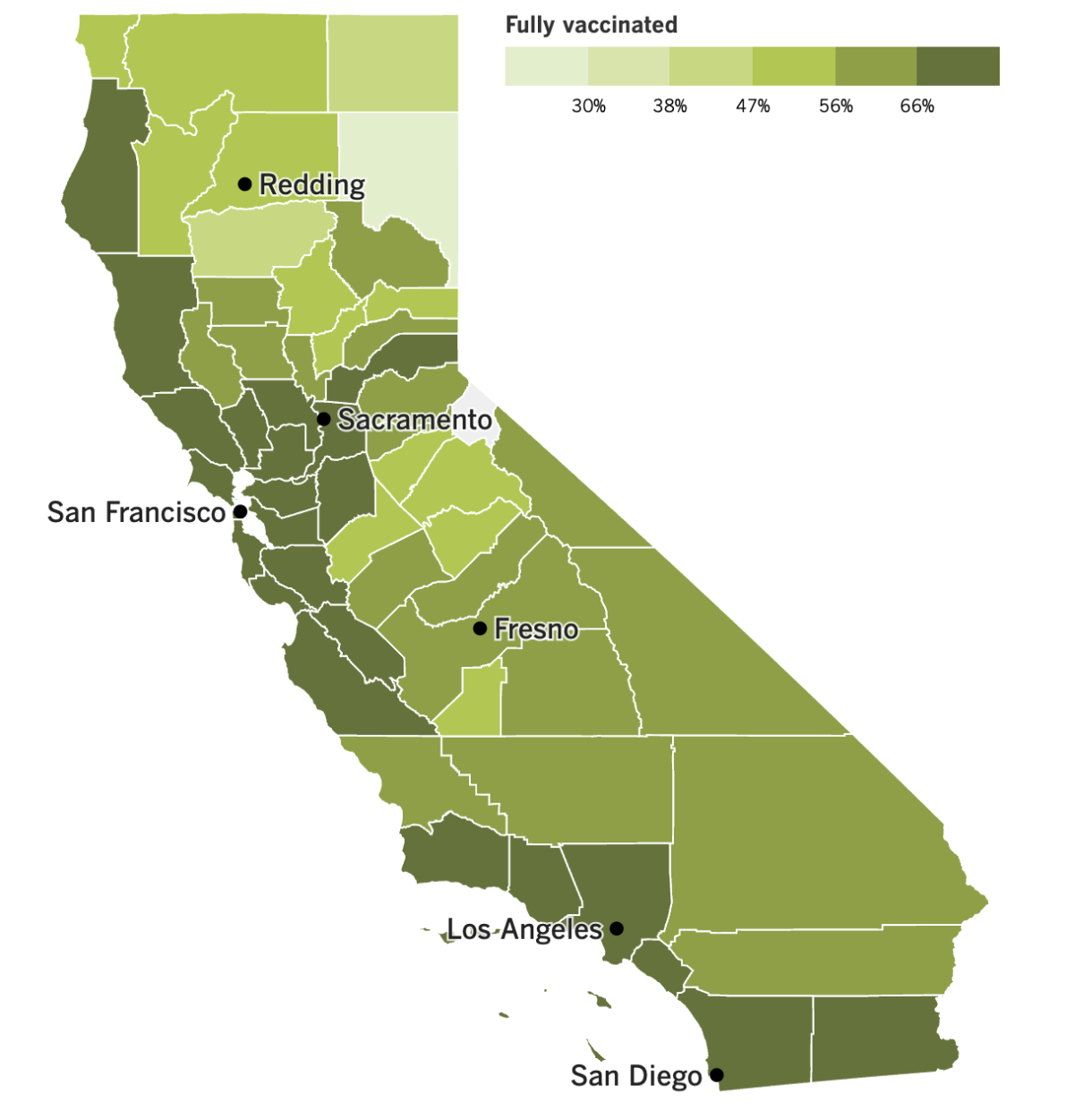

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

Congratulations Southern California! The COVID-19 community level for every single county managed to stay in the “low” zone over this last week, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC says new cases in Los Angeles County fell 6% week over week, and now stand at 72 cases per 100,000 residents per week. Deaths fell 28%, to just over 1 per 100,000 per week.

Ventura County has the lowest weekly case rate in the region, at 48 cases per 100,000 residents, and Santa Barbara, Ventura and San Bernardino counties all recorded fewer than 10 COVID-19 deaths in the last week.

But it’s not all good news for California. A report released last week found that as residents interacted with the healthcare system during the pandemic, they had profoundly different experiences based on their racial and ethnic identities.

The report from the nonprofit California Health Care Foundation said that at least once in the last few years, 69% of Black residents and 62% of Latino residents had at least one negative interaction with a healthcare provider. That compared with 48% for both white and Asian residents.

The types of negative experiences included instances in which patients felt their doctor didn’t listen to or believe what they were saying, spoke to them in a condescending manner, or didn’t treat them with respect. When the researchers accounted for demographic factors like income, gender and age, they saw that the likelihood of these types of encounters was twice as high for Black Californians as it was for their white counterparts.

The findings were based on a survey of 1,739 adults in the state. Kristof Stremikis, director of market analysis and insight at the California Health Care Foundation, called the results “deeply and profoundly disappointing,” especially since these kinds of racial disparities have persisted for “years and years.”

Here’s another racial disparity that affects some of the youngest Californians: In L.A. County, just 5% of Latino children between the ages of 6 months and 4 years and 6% of Black children in the same age group have had at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, compared with about 19% of their counterparts who are white and 22% who are of Asian descent.

The overall vaccination rate of infants, toddlers and preschool-age children is still disturbingly low — only 12% are at least partially vaccinated, and just 7% are fully vaccinated, according to data from the county’s public health department.

“We have a lot of work to do,” said Barbara Ferrer, the health department’s director.

Nationwide, 10% of kids in the youngest cohort were at least partially vaccinated by the end of 2022, and a measly 5% were fully vaccinated, according to a report published last week by the CDC.

To get a sense of how low those figures are, consider this: Two months after COVID-19 vaccines were approved for 5- to 11-year-olds, 24% of them had received their first dose. And two months after the shots were made available to adolescents ages 12 to 15, 33% of them had rolled up their sleeves at least once.

About 71% of the children younger than 5 who were included in the CDC report had information about race or ethnicity in their files. Among them, 7% were Black, 13% were Asian, 20% were Latino and 55% were white.

Speaking of vaccines, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I- Vermont) invited Moderna Chief Executive Stéphane Bancel to Washington, D.C., to explain why the price of his company’s COVID-19 vaccine would be rising by a factor of 5. Doses purchased by the federal government through the end of last year cost about $21 per dose, and Moderna had said it planned to bump that up to between $110 and $130 when it started selling the shots directly to healthcare providers and insurance companies.

Bancel accepted Sanders’ invitation. Then Moderna backed off its apparent plan to cash in.

The company explained in a statement that people with health insurance would continue to get Spikevax, its COVID-19 shot, “at no cost.” In addition, those without insurance would be able to get the vaccine for free through the company’s patient assistance program.

“Everyone in the United States will have access to Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine regardless of their ability to pay,” the statement said.

And finally, China is declaring victory over the coronavirus three months after its easing of “zero COVID” rules prompted a nationwide outbreak.

Notes from a meeting of the ruling Communist Party said that China has “decisively beaten” the pandemic. The notes said more than 200 million Chinese citizens had been treated for COVID-19, including 800,000 critically ill patients who recovered from the disease.

Those numbers are not being taken at face value. The World Health Organization, for instance, says there have been nearly 99 million infections and 119,155 deaths.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: How is wastewater being tested for the coronavirus in Los Angeles?

The L.A. County Department of Public Health tracks the virus in four places — the Joint Water Pollution Control Plant in Carson, the Lancaster Water Reclamation Plant, L.A.’s Hyperion Plant and the Tapia Water Reclamation Plant near Malibu. Samples are collected up to three times a week, and the results are weighted to reflect the size of the population served by each. (The plant in Carson serves more than 4.8 million people, for instance, whereas the one in Lancaster serves about 160,000.)

Results of this wastewater surveillance are available online on a site maintained by the state Department of Public Health. In fact, that site shows the coronavirus concentrations reported by all members of the California Surveillance of Wastewater Systems Network (which goes by the awesome shorthand Cal-SuWers).

You can also see how L.A. County is doing by checking this web page maintained by the county health department. The figure reported there compares the coronavirus concentration in wastewater now to the peak concentration from the summer of 2022.

As of Tuesday, that county had 36% as much SARS-CoV-2 in its wastewater as it did in the summer, a level that warrants “medium concern,” according to the health department.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

It’s Carnival time in Brazil, and revelers there are partying like it’s 2019.

The 2020 edition occurred before the pandemic really shut things down, but it was canceled in 2021 for the first time in more than a century. The 2022 edition was delayed by two months and wound up being a watered-down affair mostly aimed at locals.

The full-fledged return this year is a boon to the carpenters, welders, sculptors, electricians, dancers, choreographers and others whose livelihoods depend on the over-the-top parades. The festivities officially kicked off Friday and will continue through tomorrow, with an estimated 46 million expected to participate.

Brazil has recorded more COVID-19 deaths — nearly 700,000 — than any country except for the U.S. The country tallied 2,400 of those deaths in the last month, along about 300,000 new illnesses. Despite the continued threat, plenty of Brazilians are more than ready to put the pandemic behind them and celebrate.

“We’ve waited for so long,” said Thiago Varella, a 38-year-old engineer who braved rain to party in Sao Paulo. “We deserve this catharsis.”

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.