Coronavirus Today: Who’s to blame when COVID-19 kills?

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, Nov. 16. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

Sometimes there’s no one to blame when a person dies of COVID-19. Sometimes there is. This being the United States, it’s often left to the court system to sort things out.

Consider the case of Gilbert Garcia. He died last year at the age of 89 at Sunrise Villa Bradford, an assisted living facility in Placentia. His three sons have sued the facility, alleging their father would still be alive if workers there had worn gloves and other personal protective equipment, and hadn’t flouted safety guidelines by letting barbers and other outsiders in.

The company that manages Sunrise says it did the best it could to prevent coronavirus infections. Employees were required to wear masks and submit to temperature screenings, but shortages of PPE required managers to make some tough decisions — decisions they can’t be sued for thanks to the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act.

The federal law, known as the PREP Act, comes into play during a public health emergency. It provides protection against legal claims that stem from “countermeasures” such as the administration of drugs, devices and other products to prevent, diagnose or treat coronavirus infections, my colleague Emily Alpert Reyes explains.

A federal judge sided with Sunrise Senior Living Management’s argument that the Garcias’ complaints were about the “administration” of PPE — and that can include the failure to administer PPE if there’s not enough to go around. The Garcia brothers have filed an appeal, arguing that if the decision is allowed to stand, it “would strip the rights of thousands of COVID victims.”

Victims like Ricardo Saldana. The 77-year-old man died of COVID-19 at a Glendale nursing home that, according to his relatives, prevented workers from wearing gloves and masks. His case and another like it were argued in front of a federal appeals court last month.

Like the facility in Placentia, the nursing home in Glendale argued that the PREP Act shields it from claims arising from shortages of PPE. And like Garcia’s sons, Saldana’s relatives scoff at the idea that the law should protect those who are “not taking any affirmative action to protect people,” as their attorney put it.

And what about 89-year-old Catherine Apothaker, who died of COVID-19 at Silverado Senior Living in Los Angeles?

The coronavirus was brought to Silverado in the pandemic’s early days by a new resident who left New York as that city struggled to contain its own outbreaks. Although the care facility had already asked family members not to visit relatives in an effort to keep the virus out, it did not test or quarantine the new resident when he arrived a week later, according to Catherine’s daughter Helena.

“This was a disaster of their own making,” she said.

Apothaker and other relatives sued, and Silverado cited the PREP Act. A federal judge ruled in December that the circumstances described by the plaintiffs didn’t qualify as “covered countermeasures” and allowed the case to proceed in state court. Silverado has appealed the decision. (Its attorneys declined to comment on the case.)

Helena Apothaker said she’s determined to hold someone accountable for her mother’s death.

“How long is this going to take,” she asked, “until somebody says what they did was not OK?”

By the numbers

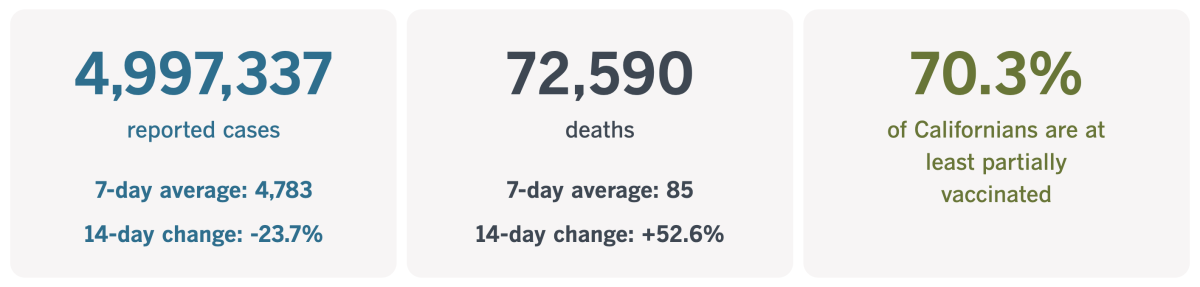

California cases and deaths as of 4:34 p.m. Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

On the lookout for the next pandemic

Someday, the COVID-19 pandemic will be over. But sooner or later, another one will put the world in peril again — and humans are hastening its arrival.

How? By erasing the barrier between human civilization and the natural world.

Mammals and birds are carriers of an estimated 1.6 million viruses. Those viruses may be harmless to their wild hosts, who’ve had time to adapt to their presence. But if one of those viruses were to jump to humans, the results could be devastating.

Any species is vulnerable to a brand-new virus because it has no immunity to protect it — not from past exposure, and certainly not from a vaccine. The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus is just the latest example of what can happen when humanity encounters a novel pathogen.

It’s not a given that a virus from another animal will be capable of doing harm to humans. For one thing, the virus would have to mutate in a specific way to be able to infect human cells. Even if that hurdle is cleared, it would likely require additional mutations to be able to spread from person to person.

But those things only matter if humans cross paths with these pathogens in the first place — and deforestation creates opportunities for that to happen, my colleagues Kate Linthicum, Emily Baumgaertner and Ana Ionova explain.

They visited Maruaga in northern Brazil, a settlement along the border of the Amazon rainforest that didn’t exist a few decades ago. Back then, humans and wildlife were separate. Today, people work in the jungle to clear it. They enter it to hunt wild game. Their dogs and chickens roam in and out, as do mosquitos.

This type of rapid land use change has caused outbreaks of malaria, Lyme disease, Zika and other maladies. In Brazil, land is cleared to make room for cattle ranches. In Asia, tropical forests are replaced with palm oil plantations. In Africa, the landscape is transformed for the sake of mining.

Scientists are trying to stay ahead of the curve by taking a census of the viruses that circulate in the primates, rodents, bats and other animals that live in the disappearing jungles. That way, if — or when — a novel virus appears in a human, it can quickly be matched to its animal source.

That information could be crucial in containing an outbreak before it grows out of hand, they say.

The most robust example of this type of biobank is the Global Virome Project. Researchers there are aiming to identify every virus that could pose a threat to humans. Had they succeeded by late 2019, the cause of Wuhan’s mysterious flu cases could have been identified much sooner, said Dennis Carroll, who runs the project.

Other scientists fret that creating biobanks is expensive and time-consuming. And it would be unnecessary if people would simply curtail their risky interactions with wild animals.

“It’s not about searching for the next virus,” said Dr. Alessandra Nava, a veterinarian and virus-hunter with the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation. “We have to stop deforestation right now.”

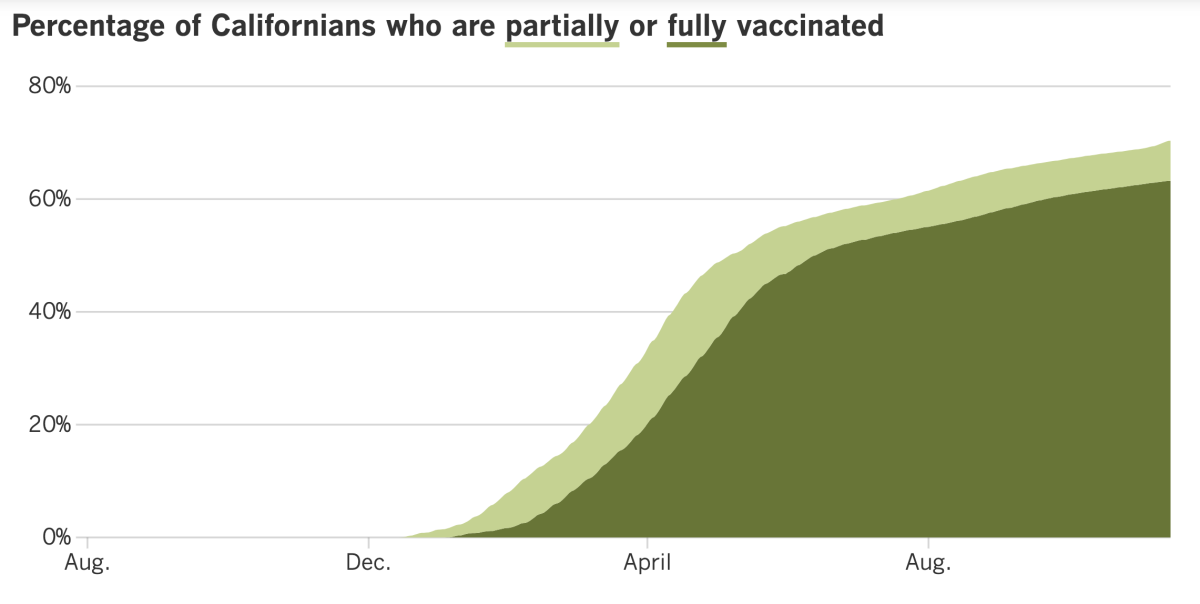

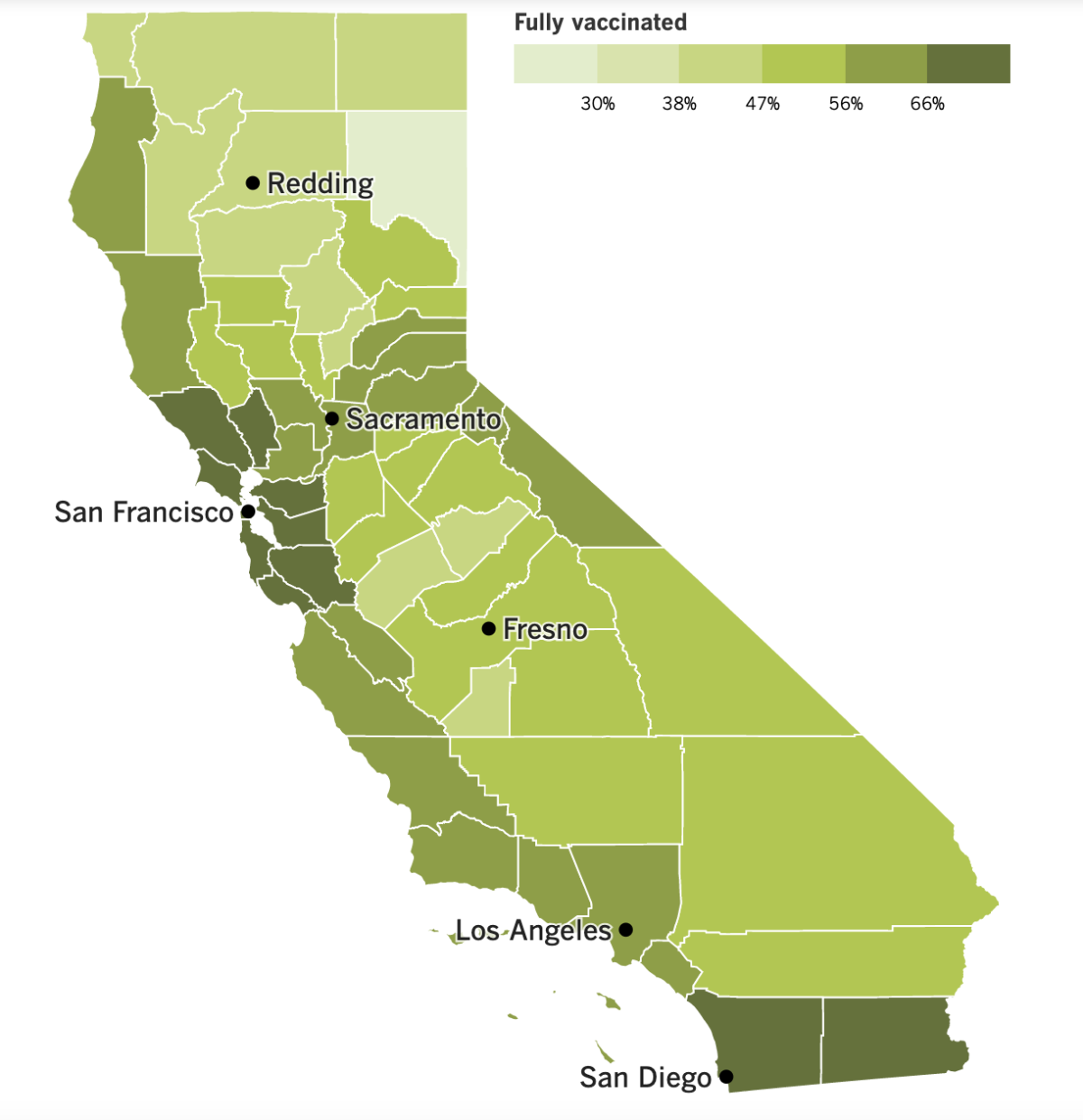

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news...

Los Angeles firefighters opposed to the city’s vaccine mandate have not only argued that it’s un-American to be forced to get a shot that protects them from a contagious and potentially disease, but also that if the mandate is allowed to stand, Angelenos will be the ones paying the price.

“It’s basic math,” a firefighter at last week’s anti-vaccine-mandate rally told my colleagues. “Response times are going to go up if they have to fire all of us.”

That argument — columnist Gustavo Arellano called it a threat — has also been made by the Los Angeles firefighters union, which has sued over the city’s vaccine mandate. But it ignores the fact that having an undervaccinated workforce is bad for the city too.

How bad? A review by The Times found that the L.A. Fire Department has spent more than $22.5 million on overtime pay related to COVID-19, and that many of those hours were needed to backfill the shifts of workers who got sick or had to quarantine themselves after being exposed to the coronavirus.

Between March 2020 and Oct. 9, 2021, more than 400,000 hours worth of work have been lost to COVID-19. Only about 70% of Fire Department employees were fully vaccinated as of last week.

Numbers like these have already convinced private-sector employers that vaccine mandates are good for business, said Dr. John Swartzberg of UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health. The same logic applies to public agencies too, he said.

New York University bioethicist Arthur Caplan told my colleague Kevin Rector that opposition to vaccine mandates is more costly when it comes from first responders. “Not only are they burdening us with the threat of spreading disease,” he said, “but selfishly they are burdening the taxpayer with the cost of having to fill in for them.”

Speaking of vaccines (when are we not?), California has something to celebrate: More than 7 out of 10 of us are now at least partially vaccinated.

That not-at-all-grim milestone was passed over the weekend, helped along by the 8% of 5- to 11-year-olds who have gotten their first doses of Pfizer and BioNTech vaccine for kids. In fact, if you only look at Californians who are eligible for a COVID-19 vaccine, nearly 75% have received at least one dose.

Those shots are more than welcome by state and local health officials, who are worried that the upcoming holiday season could look too much like last year’s fall-and-winter surge. To counter the effects of waning immunity, they’re urging adults to go ahead and get a booster shot as soon as possible.

The booster shots should reduce the risk of breakthrough infections. Although these cases tend to be mild, they can result in hospitalization or even death.

“If you think you will benefit from getting a booster shot, I encourage you to go out and get it,” said Dr. Mark Ghaly, California’s secretary of health and human services.

Need a second opinion? How about this one from L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer: “Please come in and get your booster.”

On the treatment front, Pfizer has asked the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to grant emergency use authorization for its experimental COVID-19 pill. If that authorization is granted, the therapy — which will be sold as Paxlovid — could be available in a matter of weeks.

Pfizer has said its pill cut hospitalizations and deaths by 89% in unvaccinated, high-risk adults who had early symptoms of COVID-19. The drug works best when started within three days of becoming ill, the company said. It’s not clear how much the drug would help people who are vaccinated or do not have medical conditions that make them more vulnerable to a serious case of COVID-19.

The FDA is scheduled to assess a similar drug from Merck at a public meeting at the end of November. Any pill that can be taken at home would be a welcome alternative to existing treatments, which require an IV or injection.

Pfizer also followed Merck’s footsteps by agreeing to let other manufacturers make its pill. Pfizer said Tuesday it signed a licensing deal with the Medicines Patent Pool, a group backed by the United Nations, to let generic drug companies produce Paxlovid for use in 95 countries that are home to more than half of the world’s population.

The licensing deal calls for Pfizer to waive royalties from sales in those 95 countries as long as COVID-19 remains a public health emergency. The company will also waive royalties from sales in low-income countries.

Finally, Austria has implemented a nationwide lockdown to get its coronavirus surge under control — but only for the country’s roughly 2 million residents ages 12 and up who are not vaccinated against COVID-19. They can leave their homes only to go work or school, buy groceries, take a walk — or get vaccinated.

Those who violate the lockdown order can be fined up to up to 1,450 euros, or $1,660. It is scheduled to last until at least Nov. 24.

“We really didn’t take this step lightly,” said Chancellor Alexander Schallenberg.

Around 65% of Austrians are fully vaccinated, a rate Schallenberg called “shamefully low.”

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: What should I do about a COVID-19 booster shot?

It depends on your particular situation.

For some people, a booster shot is definitely in order. For instance, if you got the Johnson & Johnson vaccine more than two months ago, you’re eligible for a booster shot. And if you’re an immunocompromised person who got the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna vaccine, you’re advised to get a booster if it’s been at least 28 days since your second dose.

Most other adults who got a two-dose vaccine are able to get a booster shot as well, so long as six months have elapsed since their second dose. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has identified several eligibility groups:

- People who are at least 65 years old.

- People who live in nursing homes or other long-term care facilities.

- People who work or live in high-risk settings, such as hospitals, schools, grocery stores and correctional facilities.

- People with a medical condition that makes them more vulnerable to a severe case of COVID-19.

The CDC recently expanded its list of qualifying medical conditions, and it’s now so broad it encompasses most vaccinated Americans. In addition to things like cancer, asthma and heart disease, the list now includes people with diabetes, people who are current or former smokers, and people who are overweight as well as those who are obese. Researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital estimate 89% of people who have met the time requirement now qualify for a booster.

The state of California has gone one further by giving permission for any adult to get a booster shot if the necessary amount of time has passed.

“Do not turn a patient away who is requesting a booster,” Dr. Tomás Aragón, the state’s director of public health, wrote in a letter to vaccine providers.

If you’re eligible for a booster and opt to get one, you have the option of choosing a different vaccine this time around. Our interactive quiz will walk you through the decision-making process.

For a refresher on how to get a booster dose, check out this previous edition of the Coronavirus Today newsletter.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Keep in mind that supplies are limited, and getting one can be a challenge. Sign up for email updates, check your eligibility and, if you’re eligible, make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.