Coronavirus Today: Why booster shots are so complicated

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Friday, Sept. 24. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

Looking back, the decision about who should be eligible for COVID-19 vaccines was easy: As long as they‘re safe and effective, they ought to be available to everyone.

After all, no one had reliable built-in immunity to the novel coronavirus, and vaccines were the surefire way to get it. (People who have recovered from an infection have varying amounts of antibodies, so the shots ensure they have a safe baseline level of protection.)

Shortages in the early months of the vaccine rollout forced health officials to think hard about who should have access to them first, but once production had ramped up, the goal was to get a shot (or two) in the arms of anyone old enough to be eligible.

At first glance, the situation with booster shots might seem similarly straightforward — indeed, President Biden didn’t think he was going out on a limb when he said boosters would be available the week of Sept. 20. As it happens, his pledge was fulfilled with a day to spare. But the process turned out to be more convoluted than expected.

When Dr. Rochelle Walensky signed off on Pfizer and BioNTech’s booster shots in the wee hours of Friday morning, she kicked off a major new phase in the U.S. vaccination drive. For the most part, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention accepted the recommendation of an expert advisory panel, which had endorsed a third dose for people 65 or older, residents of nursing homes and those age 50 to 64 with health problems that make them more vulnerable to a severe case of COVID-19.

But she overruled the panel and recommended that boosters also be made available to adults under 65 whose jobs put them at heightened risk of coronavirus exposure. That category includes healthcare workers.

Although that decision put her at odds with her own advisors, it did align with the authorization issued Wednesday by the Food and Drug Administration.

Initially, Pfizer sought FDA approval to offer a third booster dose to anyone who had received a second dose at least six months earlier. But an FDA advisory panel pushed back, overwhelmingly rejecting that blanket approach. Instead, the panel voted to endorse emergency-use authorization of boosters only for specific, higher-risk groups.

How did something that seemed like a no-brainer get so complicated? You can blame the data on vaccine effectiveness, which show that, for many people, the vaccine is working too well to warrant booster shots.

One slide the CDC advisors examined this week showed how effective the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines have been at preventing people from being hospitalized with COVID-19. The results were broken down into two periods: from January to May and from June to August.

For Pfizer vaccine recipients age 65 and older, there was a clear drop-off over time. The vaccine was 86% effective at preventing COVID-19 hospitalizations in the first five months and 73% effective in the following three months. That decline was considered statistically significant — in other words, too large to be due to chance.

Likewise, in those ages 50 to 64, the Pfizer vaccine’s effectiveness at preventing COVID-19 hospitalizations dropped from 93% in the first five months to 84% in the next three months. That difference, however, wasn’t large enough to rule out a statistical fluke.

The data looked quite different for younger adults. Those ages 30 to 49 had the same level of vaccine effectiveness in both periods: 82%. And for those 18 to 39, the vaccine’s effectiveness seemed to increase, from 82% to 85% (though that could have been a statistical fluke as well).

On the one hand, the fact that the Pfizer vaccine’s effectiveness at preventing COVID-19 hospitalizations was in the 82%-to-85% range for adults under 50 might seem disappointing, considering that it hit 86% and 93% for older recipients. On the other hand, it’s hard to look at the data and argue that the protection offered by the shots is wearing off.

That’s why Dr. Pablo Sanchez of Ohio State University, a member of the CDC advisory group, argued against offering the boosters so broadly. “We have a very effective vaccine, and it’s like saying, ‘It’s not working,’” he said. “It is working.”

Dr. Matthew Daley, a CDC advisor from Kaiser Permanente Colorado, concurred. For most people, if you’re not in a group recommended for a booster, “it’s really because we think you’re well-protected,” he said. “This isn’t about who deserves a booster but who needs a booster.”

(In case you’re curious, Moderna’s vaccine experienced much less of a drop-off in effectiveness at preventing COVID-19 hospitalizations. For those 65 and older, it went from 91% in the first five months to 86% in the next three months; for those 50 to 64, it dipped from 93% to 91%; for those 30 to 49, it rose from 85% to 99%; and for those 18 to 29, it dropped from 91% to 82%. None of those changes were statistically significant.)

The CDC advisors spent some of their time lamenting that they lacked a surefire way to measure whether vaccine protection really was waning, and by how much. Levels of coronavirus antibodies decline over time, but those antibodies aren’t the immune system’s only weapon against infection. Research aimed at finding better correlates of immunity is ongoing.

Walensky agreed that the booster data currently available “are not perfect.” But she said they’re good enough “to make a decision about the next stage in this pandemic.” When the CDC and FDA get better information on how the vaccines are holding up, they can adjust their recommendations about booster shots accordingly.

There was one thing everyone agreed on: The most important goal remains getting first doses into the arms of those who haven’t received any vaccine at all.

“We can give boosters to people, but that’s not really the answer to this pandemic,” said Dr. Helen Keipp Talbot of Vanderbilt University. “Hospitals are full because people are not vaccinated. We are declining care to people who deserve care because we are full of unvaccinated, COVID-positive patients.”

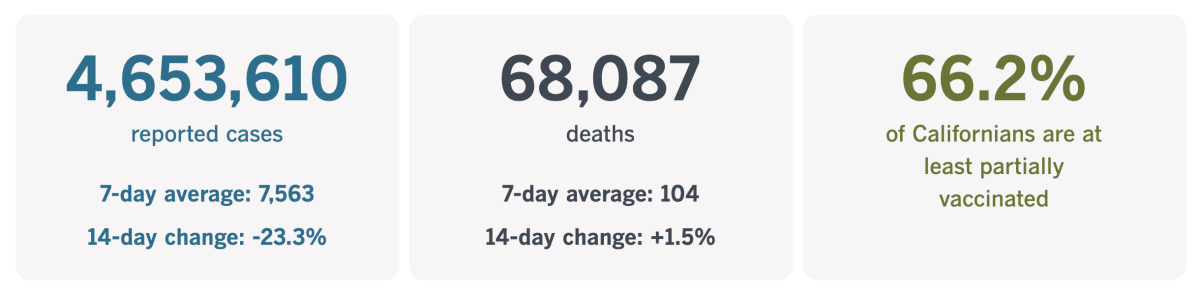

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 5:50 p.m. Friday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

When it comes to vaccines, what counts as a ‘sincerely held belief’?

With vaccine mandates — and opposition to them — on the rise across the country, my colleague Jon Healy wryly observes that “more workers are finding religion. Or rather, ‘sincerely held religious beliefs’ that, they say, prevent them from getting the shots.”

It’s hardly a surprising development. The vaccines have become so polarizing that some people would say or do almost anything to steer clear of them. That got me to thinking about what it takes for for a belief to qualify as “sincerely held.”

A few weeks ago, we talked about why vaccination mandates include a religious exemption in the first place. After all, the coronavirus doesn’t care about your faith; its only concern is to latch onto your cells, burrow inside and replicate as much as possible.

Some legal experts argue that employers, government agencies or other promulgators of vaccination mandates aren’t required to include religious exemptions. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission encourages employers to take “reasonable” actions to eliminate a “conflict between religion and work,” but they aren’t obligated to do anything that would create an “undue hardship.”

All of this presumes that a person’s objection to vaccines is rooted in a sincerely held belief. What exactly does this mean?

For starters, it doesn’t have to be based on the official policy of a church or other religious institution. The Pope may not object to COVID-19 vaccines — indeed, he’s actively encouraging people to get them — but that doesn’t preclude Catholics from coming to a different conclusion.

The EEOC says the federal law that protects religious objectors also extends to those with sincere “ethical or moral beliefs.” Apparently, religion need not be a factor.

In addition to the federal statute, California has its own law that bans discrimination based on “beliefs, observances, or practices, which an individual sincerely holds and which occupy in his or her life a place of importance parallel to that of traditionally recognized religions.”

Despite all this leeway, legal experts say exemptions to vaccination mandates aren’t available to people who object on political or ideological grounds. (An exemption for a bona fide medical reason is acceptable.) Employers who suspect that a stated religious objection may be motivated by politics or ideology are allowed to ask questions to get to the bottom of the matter.

New York University bioethicist Arthur Caplan has been thinking about this. In an essay published this week in Stat, he likened today’s COVID-19 vaccination objectors to the young men (like him) from half a century ago who opposed the war in Vietnam but faced the prospect of being drafted and forced to fight anyway.

“The overlap in the moral wrangling over exemptions is uncanny, particularly the dubious nature of sudden religiosity to resist a mandate,” he wrote.

Back then, the Supreme Court ruled that sincerely held antiwar beliefs — religious or secular — could exempt someone from military service. As a result, thousands of draft boards across the country were charged with vetting would-be conscientious objectors.

“Some of my contemporaries managed to persuade their draft boards of their sincere objections to service and wound up being given alternative jobs in nursing homes and homes for those in mental institutions of the time,” Caplan wrote.

The boards were far from perfect, but Caplan argues that they (or something like them) ought to be re-created now to adjudicate requests for religious exemptions to vaccines.

“Simply allowing individuals to claim whatever they wish to avoid resolving a plague or for that matter government required service in a war is not good public policy,” he concluded.

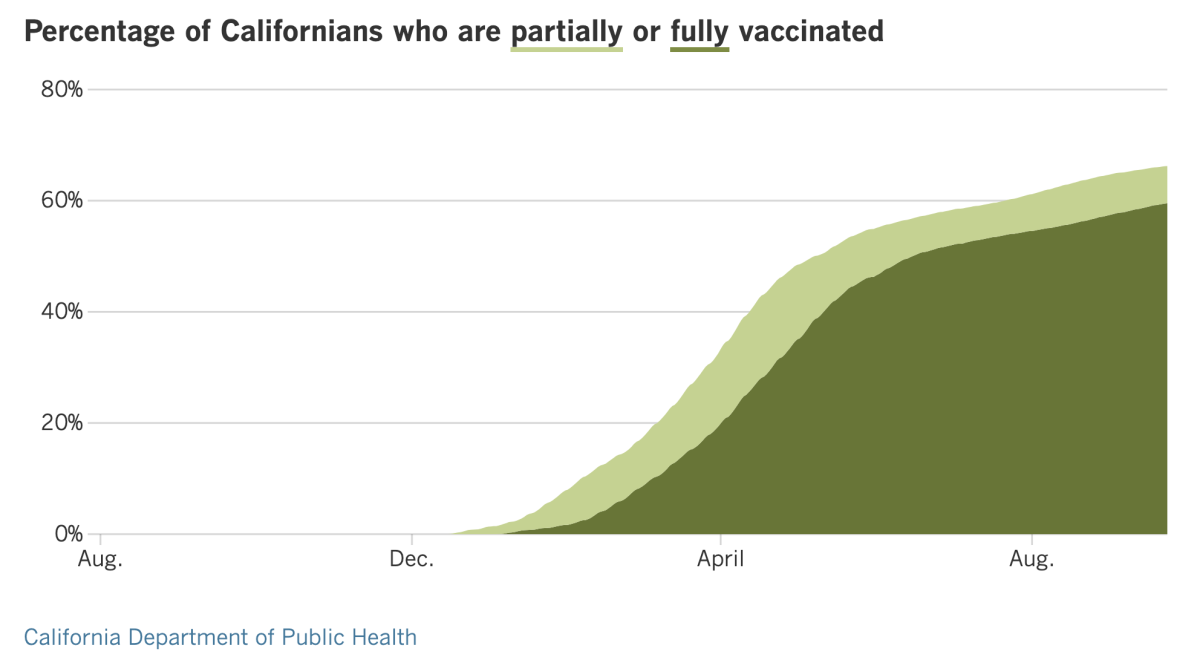

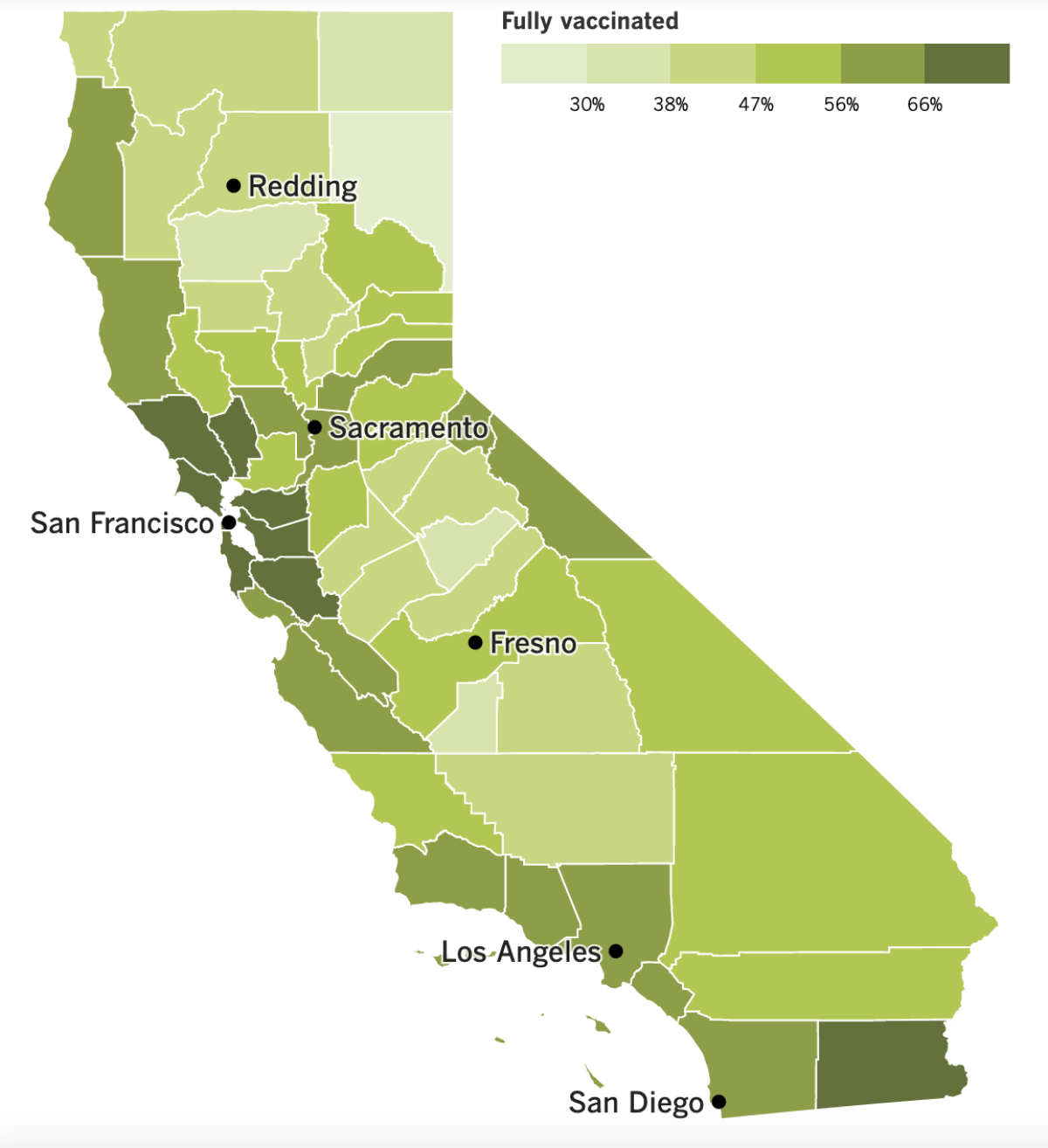

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

In other news ....

Labor Day was nearly three weeks ago, but Angelenos have something to celebrate now: Thanks to a relatively high vaccination rate and other COVID-19 precautions, Los Angeles County avoided sparking a coronavirus surge over the holiday weekend.

Holidays have often led to a spike in cases, said L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer. With people attending more gatherings and perhaps feeling lax about social distancing and masking, the virus has more opportunities to spread. But this time, cases continued to fall and are at their lowest level since mid-July.

That doesn’t mean it’s time to ease up, Ferrer said. On the contrary, it’s all the more reason to redouble efforts to lift the percentage of fully vaccinated county residents above 60.1%, where it is now. Infectious disease experts estimate that at least 84% of residents will need to have some immunity for the community to achieve herd immunity against the highly transmissible Delta variant.

Relaxing the county’s universal indoor mask mandate or other public safety measures now could lead to a new cycle of cases, hospitalizations and deaths in the autumn and winter, when conditions will be more conducive to viral spread. Boosting vaccinations would put us in a better position to meet that threat, Ferrer said.

“Waiting until spread ... is once more very high before acting doesn’t reflect the reality of this pandemic and the destructive potential of the virus,” she said.

Here’s another consequence of dragging our feet on vaccinations: The average age of Californians who die of COVID-19 is falling.

If you look at all COVID-19 deaths in the state since the pandemic began, the average age of victims is 73. If you go back only to April — when vaccines were still limited to higher-risk groups — the average age falls to 67. And if you focus only on August and September — a period when the vast majority of COVID-19 deaths were among the unvaccinated — the average age is 66.

These figures come from data collected by the California Department of Public Health. Officials there say the pattern fits with the disparate vaccination rates for residents of various age groups. According to The Times’ vaccine tracker, 78% of Californians between the ages of 50 and 64 are fully vaccinated, as are 74% of those 65 and older. By contrast, 67% of people ages 18 to 40 are fully vaccinated, as are 54% of adolescents between 12 and 17.

Here’s another indication of the link between vaccines and mortality: A year ago, men accounted for 54.6% of COVID-19 deaths. But they’ve been less likely than women to get vaccinated — they account for 49.7% of Californians ages 12 and up but have received only 47.6% of vaccine doses administered in the state.

Now that women have the vaccination advantage, they have a bigger mortality advantage. As of last month, 58.9% of the state’s COVID-19 deaths were in men.

Vaccines and masks get the most attention, but rapid COVID-19 tests are another important piece of the pandemic response. President Biden is counting on millions of the tests to help beat back the Delta-fueled surges that are overwhelming hospitals around the country. But the more the tests are needed, the harder they are to find.

In many parts of the country, rapid tests have disappeared from store shelves. Manufacturers scaled back production as demand plummeted over the summer, and they warn that it will take weeks to ramp up again and get their products back in stores.

The shortage is another reminder that the U.S. still lacks a comprehensive testing strategy. Without one, some local governments have had to stop offering free rapid tests to the public. In Mesa County, Colorado, for instance, officials decided to save their limited supplies for school districts.

This month, Biden said the government would spend $2 billion to purchase 280 million rapid tests. He said the federal government would invoke the Defense Production Act to make sure test makers have the materials they need.

The moves should help stabilize supplies, but critics said actions like these should have been taken months ago.

“We can’t let the market determine our testing supplies, which is what happened here,” said Scott Becker, executive director of the Assn. of Public Health Laboratories. “These tests are essential for public health purposes, so we have to have supply at all times.”

In other news, Florida, which has the second-highest COVID-19 death rate in the nation, has a new surgeon general. Dr. Joseph Ladapo was named to the position this week by Gov. Ron DeSantis, and as columnist Michael Hiltzik writes, the two are in a tight race for the title of “promoter of the most ghoulishly irresponsible pandemic policies in the nation.”

When it comes to the coronavirus, DeSantis is perhaps best known for his relentless efforts to prevent Florida school districts from implementing mask mandates that would protect the health of their students and teachers. The governor’s ban on mask mandates was briefly overturned by a state court judge, but an appeals court reversed that decision two weeks ago.

Ladapo will give him a run for his money. He has raised doubts about whether COVID-19 vaccines are safe and effective. (They are.) He has been a cheerleader for debunked treatments like the antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine and the anti-parasitic drug ivermectin. An editorial in the Orlando Sentinel labeled him a “COVID crank.”

In his first official act after taking office, Ladapo signed an order that prevents school districts from requiring children to quarantine if they’ve been exposed to someone with a confirmed coronavirus infection. Instead, families will have the “sole discretion” to decide whether their exposed children present a safety hazard to classmates and teachers.

On a more positive note, the Lasker Awards were announced Friday. These are sometimes referred to as “America’s Nobels” (though unlike the Nobels, they’re focused exclusively on advances in medical science).

Among this year’s winners are Katalin Karikó of BioNTech and Dr. Drew Weissman of the University of Pennsylvania, who were honored for their work that made mRNA vaccines possible.

Over decades, Karikó overcame countless hurdles in pursuit of her goal: using messenger RNA to turn human cells into factories capable of making a desired protein. Weissman had been trying to create an HIV vaccine, and Karikó thought mRNA might be able to make it happen. After the pair teamed up, they created an experimental Zika vaccine that worked in mice and monkeys.

But their technology really paid off after the SARS-CoV-2 genome was sequenced. Teams of scientists from Pfizer and BioNTech and from Moderna and the National Institutes of Health quickly created vaccines that gave cells instructions for making copies of the coronavirus spike protein. Those copies last long enough to prompt the immune system to ready its defenses in case it ever meets the coronavirus for real.

“To date, hundreds of millions of people throughout the world have been injected with one of these two vaccines,” the prize announcement explains. “In addition to providing a tool for quelling a devastating pandemic, the innovation is fueling progress toward treatments and preventives for a range of different illnesses.”

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: When can young children get vaccinated for COVID-19?

California health officials unveiled a COVID-19 Vaccine Action Plan on Thursday that says kids under 12 will be able to get the shots at school-based clinics, medical offices and pharmacies. It projects that by the first week of November, up to 626,000 doses could be administered per week to children between the ages of 5 and 11.

That assumes the FDA and CDC sign off on a vaccine for this age group on Oct. 15. The state Health and Human Services Agency also anticipates having a version of the vaccine for children 4 and under on Dec. 1.

For now, those dates are just educated guesses. The exact timing depends on how soon vaccine makers submit their clinical trial data to the FDA, how long it takes the agency to evaluate those results and whether regulators are persuaded that the shots are safe and effective.

The first of those steps is expected to occur by the end of September, according to Dr. Bill Gruber, a Pfizer executive and pediatrician. On Monday, he said a lower dose of the formulation used for adolescents and adults prompted younger children to produce the same level of coronavirus antibodies.

Dr. Peter Marks, the FDA’s vaccine chief, has said that once the agency gets its hands on the Pfizer data, he hopes to have a decision “within a matter of weeks rather than a matter of months.”

There’s reason to be optimistic. As my colleague Jessica Roy points out, Pfizer submitted its initial application for emergency-use authorization of the vaccine on Nov. 20, 2020; that authorization was granted three weeks later, on Dec. 11.

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is currently the only one authorized for use in minors, and it’s likely to be the first available for young children. The FDA is now vetting Moderna’s application to authorize its vaccine for adolescents between 12 and 17, and a clinical trial involving younger children is underway.

Johnson & Johnson is conducting a Phase 3 clinical trial of its vaccine in adolescents ages 12 to 17. If the preliminary results are good, the company will follow up with tests in children as young as 2.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

Scenes of empty, barricaded streets were common in the early days of the pandemic, but they had started to feel like ancient history — until a coastal city in southern Vietnam met the Delta variant.

Vung Tau, just outside Ho Chi Minh City, had managed to evade the coronavirus for well over a year. Life was pretty much normal. That changed in late July, after the city registered its first infection with the Delta variant, and a lockdown was ordered soon after.

Indeed, half of Vietnam’s population is under lockdown orders after the country racked up more than 700,000 infections and 17,000 deaths in the past four months or so.

Now residents are being asked to leave their homes for necessities only once a week. Barbed wire, door panels and steel sheets form makeshift roadblocks to limit people’s movements.

The atmosphere reminds some people of the war 50 years ago. Vietnamese officials want people to take the coronavirus just as seriously. “Fighting this pandemic is like fighting the enemy,” authorities say.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Keep in mind that supplies are limited, and getting one can be a challenge. Sign up for email updates, check your eligibility and, if you’re eligible, make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.