Coronavirus Today: Tokyo Olympics without the fanfare

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Friday, July 9. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

What happens when an unstoppable force meets an immovable object?

When the unstoppable force is the coronavirus, and the immovable object is the Tokyo Olympics, the answer is that history will be made.

For the first time ever, the Summer Games will be held without spectators in the stands.

Japanese officials made the announcement Thursday as they declared that a state of emergency for Tokyo will go into effect Monday and continue until Aug. 22. That window includes the Olympics, which begin July 23 and end Aug. 8.

“Taking into consideration the impact of the Delta strain,” said Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, “and in order to prevent the resurgence of infections from spreading across the country, we need to step up virus prevention measures.”

A century ago, the virus responsible for the 1918 flu pandemic infected roughly 1 out of every 3 people on the planet and killed at least 50 million. But that outbreak had pretty much subsided by the fall of 1919, and the Antwerp Olympics the following summer were attended by large crowds.

It could have been worse for the roughly 11,000 Olympic athletes slated to compete in Tokyo — the Games could have been canceled altogether. Indeed, Tokyo officials had previously implied that they’d pull the plug on the whole thing if there were no fans in the stands.

The Japanese government and the International Olympic Committee acknowledged that the situation is less than ideal. But the decision was made “in the interest of safe and secure Games for everybody,” they said in a statement, adding that they “deeply regret for the athletes and for the spectators that this measure had to be put in place.”

Athletes already knew they wouldn’t be competing in packed stadiums. Olympic organizers had previously barred foreign spectators and limited tickets for Japanese fans to 50% capacity, with a maximum audience size of 10,000. Now, even those smaller crowds will be gone.

Marko Vavic, a member of the U.S. men’s water polo team, said he and his teammates had been counting on fans to motivate them when they play their opening match against Japan on July 25.

“We were really excited, expecting it to be loud and rowdy,” Vavic said. “I definitely feed off the energy and the ruckus they cause.”

Understanding the reason for the decision didn’t necessarily make it easier to accept.

“I’m a little bit heartbroken,” said U.S. diver Krysta Palmer. “I also feel heartbroken for Tokyo and the country of Japan. It’s tough for them not being able to hold a normal Olympics.”

It’s still possible that fans will be allowed to watch competitions held outside of Tokyo, in places where the state of emergency doesn’t apply. And spectators may be allowed at the Paralympic Games, since they won’t start until Aug. 24.

But a lot will depend on the coronavirus — particularly the highly transmissible Delta variant. Delta is partly responsible for the recent increase in infections in Tokyo, where the number of new cases is within striking distance of the peak seen in mid-May, at the height of Japan’s third surge.

“The infections are in their expansion phase, and everyone in this country must firmly understand the seriousness of it,” said Dr. Shigeru Omi, a top government medical advisor. “The period from July to September is the most critical time for Japan’s COVID-19 measures.”

In other words, the Tokyo Olympics will end in August, whether fans are there or not. But the pandemic will continue.

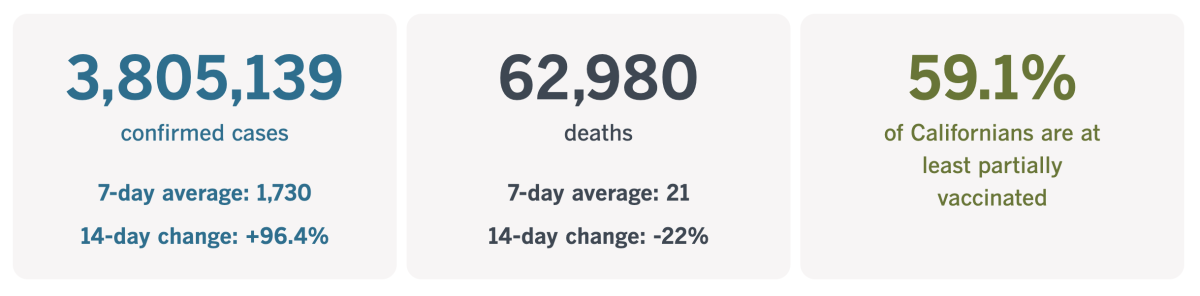

By the numbers

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 5:30 p.m. Friday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

What the pandemic taught a long COVID patient

The coronavirus outbreak has taught us a lot about ourselves: how we cope with uncertainty, who we can trust and what we’re willing to do to protect ourselves.

My colleague Sandhya Kambhampati learned lessons like these the hard way — not as a data journalist covering the pandemic, but as a patient who developed the baffling condition known as long COVID.

Kambhampati was among the first Los Angeles County residents to cross paths with the coronavirus. Her first symptoms of COVID-19 appeared on April 2, 2020. At the time, the number of confirmed coronavirus infections in the county had just crossed the 4,000 mark. (It’s now over 1.2 million.)

She knew something was wrong when she found herself wheezing, suffered severe body aches, developed a 103-degree fever that hung on for a month and lost her senses of taste of smell. She recovered enough to return to work (virtually) in May, but she was hardly her old self. She felt dizzy, had trouble going up and down stairs and slept at least 10 hours a night.

The healthcare providers who ideally would have helped her turned her away. By then, they had their hands full with other COVID-19 patients. Kambhampati’s symptoms could have been anything. She was told her “cold” might go away on its own. It didn’t. When her symptoms flared up, she was told she was suffering an anxiety attack. She wasn’t.

So she approached the problem like a data journalist, taking notes about her condition and keeping track of her heart rate and blood oxygen saturation. Those records helped her doctors when, 195 days after her initial COVID-19 diagnosis, she finally got the care she needed.

“Being a COVID long hauler has taught me to be more fearless, resilient, meticulous and inquisitive than I ever was before,” Kambhampati writes in this first-person account.

Through 135 appointments with 32 doctors who ordered 47 tests and countless blood draws, she learned to advocate for herself — and she learned that this included educating herself about all of these specialists and procedures.

She is grateful that she could turn to the many doctors in her family for assistance, and she recognizes how fortunate she is to have them in her camp. Even her ability to speak English is a privilege she doesn’t take lightly.

The pandemic taught Kambhampati to stand up for herself. It taught her that “surviving and recovering are not the same thing,” she writes. Perhaps most important, it has taught her “not to take no for an answer” and “made me see how fragile life can be.”

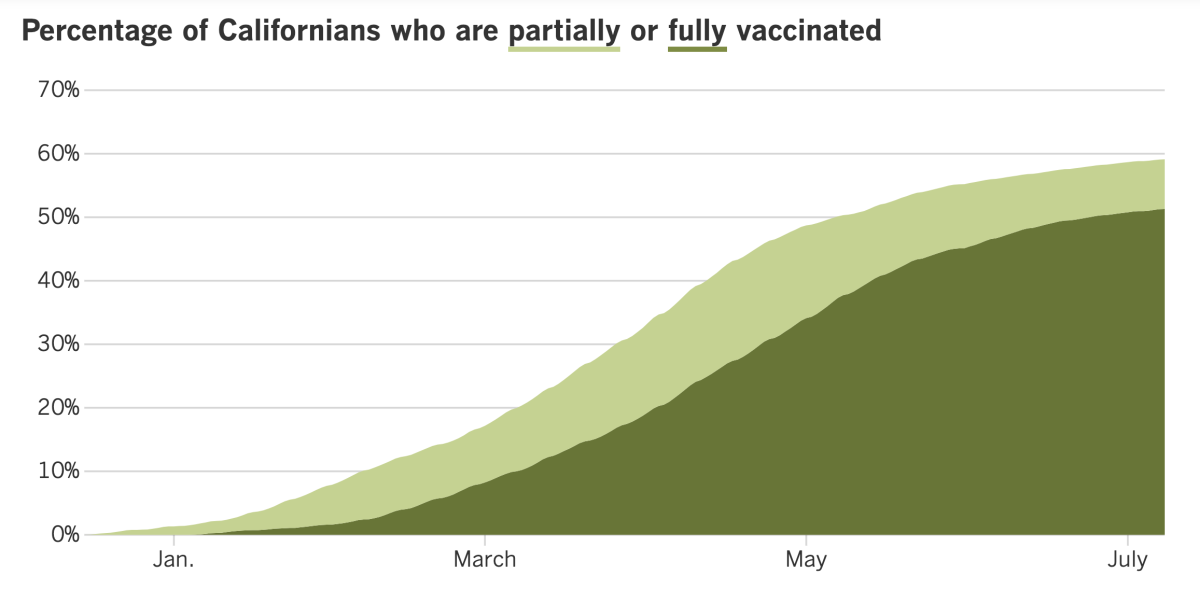

California’s vaccination progress

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

In other news ...

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention relaxed its COVID-19 guidelines for schools Friday, saying teachers and students who are fully vaccinated don’t need to wear masks inside school buildings.

The CDC is not advising schools to require the shots for teachers or for kids who are old enough to get them. Nor did it offer guidance for how teachers could tell which students had been vaccinated, or how parents could tell which teachers had been immunized. That could set up an awkward dynamic in districts that follow the new advice.

“It would be a very weird dynamic, socially, to have some kids wearing masks and some not,” said Elizabeth Stuart, a public health expert at John Hopkins University. “And tracking that? Teachers shouldn’t need to be keeping track of which kids should have masks on.”

They won’t have to in California. State health officials announced that masks will be required in schools here, despite the CDC’s new position.

“Masking is a simple and effective intervention that does not interfere with offering full, in-person instruction,” said Dr. Mark Ghaly, secretary of the California Health and Human Services Agency. “At the outset of the new year, students should be able to walk into school without worrying about whether they will feel different or singled out for being vaccinated or unvaccinated — treating all kids the same will support a calm and supportive school environment.”

The CDC also said schools should place students’ desks three feet apart if possible, but that doing so is not a mandate. Ghaly said some California schools would be able to make that happen, but when that degree of physical distancing isn’t possible, “we will align with the CDC by implementing multiple layers of mitigation strategies.”

That’s where the indoor mask rule comes in. (Schools generally don’t require masks during recess or in most other outdoor situations.) Robust testing programs will also help fill in the gaps, Ghaly said.

If current trends continue, a lot of those coronavirus tests will be turning up positive in Los Angeles County. The county has reported an average of 521 new cases per day over the last week. That is three times higher than two weeks ago, according to data compiled by The Times.

What’s more, the test positivity rate has shot up in L.A. County, from 1.2% last week to 2.5% as of Thursday.

These upticks in infections represent just the first link of a potentially devastating chain. Some of these newly infected people will become sick enough to go to the hospital, and some will die of COVID-19.

L.A. County is already seeing an increase in hospitalizations, with 320 COVID-19 patients as of Wednesday — a 51% increase over the past four weeks. Deaths remain low, at about five per day.

Around the world, the pandemic’s death toll has surpassed the 4 million mark, according to trackers at Johns Hopkins University. That’s equivalent to losing the entire population of the city of Los Angeles. Actually, it’s worse, because experts agree that the official records overlook many cases that are never diagnosed or are deliberately concealed.

The official death toll is bound to get worse, thanks to a trifecta of factors. The first is the rise of Delta and other coronavirus variants that are more difficult to manage than their predecessors. The second is uneven access to vaccines around the world. And the third is a trend toward relaxing COVID-19 restrictions in wealthier countries that are eager to put the pandemic behind them.

It all adds up to “a toxic combination that is very dangerous,” warned Ann Lindstrand, a top immunization official at the World Health Organization.

Finally, scientists have discovered 13 key locations in the human genome that may influence a person’s susceptibility to a coronavirus infection or their risk of developing a severe illness.

It’s not yet clear how — or even if — the genes in these 13 places may affect what happens to a person who crosses the coronavirus’ path. But some of these genes have previously been linked to lung function or the workings of the immune system.

Though still in its early stages, this type of research could help explain why the coronavirus triggers severe disease in some people and practically no symptoms in others. The findings could also help researchers design or repurpose treatments for COVID-19, experts said.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: How well do COVID-19 vaccines work against the Delta variant?

Quite well, according to my colleague Melissa Healy.

Multiple studies indicate that when the vaccines are at full strength — that is, two weeks after the last dose in a series — they work almost as well against the Delta variant as they do against earlier coronavirus strains.

For instance, real-world data from the U.K. indicate that the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was 88% effective at preventing cases of COVID-19 that result from an infection with the Delta variant. And antibodies produced in response to two doses of the vaccine were able to neutralize Delta, albeit with a small reduction in effectiveness.

Tests of blood serum from eight people who were fully vaccinated with the Moderna vaccine found that the efficiency with which they were able to thwart an infection with the Delta variant was reduced by about half. But since the vaccine produces far more antibodies than are needed, there should be “no effect on the vaccine’s protection,” Healy explained.

The situation with the single-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine is somewhat less clear. The company said it tested serum from eight people who got its vaccine and saw a strong immune response to the Delta variant. The company didn’t share details about those tests, however.

There’s some reason to be optimistic: A study of the AstraZeneca vaccine — which is widely used in the United Kingdom — found that at full strength, it was 60% effective at reducing the risk of COVID-19 caused by the Delta variant. The J&J vaccine bears a strong resemblance to the AstraZeneca one.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

California’s COVID-19 vaccination campaign may be stalling, but veterinarians at the Oakland Zoo are doing their part by inoculating some of the animals in their care, including a ferret named Archie.

The zoo began its immunization drive last week, starting with two tigers, Ginger and Molly. Black bears, grizzly bears and mountain lions were also in the first group of vaccine recipients. They’ll be followed by chimpanzees and other primates, fruit bats and pigs, the zoo said.

The experimental two-dose vaccine was donated by Zoetis, an animal health company that developed the shots in response to a request from the San Diego Zoo. A troop of eight gorillas at the zoo’s Safari Park came down with COVID-19 in January. All of them recovered.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Sign up for email updates, and make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Need more vaccine help? Talk to your healthcare provider. Call the state’s COVID-19 hotline at (833) 422-4255. And consult our county-by-county guides to getting vaccinated.

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.