Coronavirus Today: Our progress on vaccine equity

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Melody Petersen, and it’s Thursday, April 15. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

In early March, California began devoting 40% of its vaccine supply to underserved communities, where people have died in much higher numbers.

Did that effort end up helping such communities in Los Angeles? Times reporters Luke Money and Matt Stiles analyzed the data to find out.

They learned the county has made big strides in administering the vaccines in the communities of color that have suffered most from the pandemic. Yet those neighborhoods continue to lag far behind both wealthier areas and the county as a whole.

Some neighborhoods in South L.A. — where the spread of the coronavirus was particularly devastating — have seen the biggest rise in the number of residents receiving at least one dose since March 1, the data show. Other areas that saw significant jumps include Thai Town in Hollywood, Lennox and Cudahy.

Yet these areas still have vaccine rates below the county average.

“We still have a long way to go,” said L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer.

The earmarking of vaccines for underserved communities became more crucial Thursday, as California began allowing all residents age 16 and older to book appointments. That will add millions more people to the vaccination line.

For months, health officials have said the vaccine rollout has been hindered by the same inequities that have plagued healthcare access for generations.

For example, those who were able to take time off work to travel to a far-flung vaccine clinic, or who could constantly refresh a web page to snag an appointment, had a clear leg up over people with less flexible jobs or more limited access to transportation or the internet.

“People who can travel, who have cars, who don’t have jobs that make it hard for them to spend a lot of time on the computer looking for appointments, those were all people who were advantaged — particularly in the early days of the vaccine rollout,” Ferrer said.

Take Cheviot Hills, for example. Roughly 37% of the 16-and-older population of the Westside community had already received at least one vaccine dose by March 1. That proportion has since grown to nearly 64%.

At the other end of the spectrum is University Park in South L.A., where only about 6.5% of residents had at least one shot as of March 1. That number has since grown markedly, to a bit more than 25%, but still lags well behind the county average of 37%.

And the data continue to show a stubborn gap in the rate of vaccination among Black and Latino residents, compared with other groups.

As of April 4, 22.7% of Black and Latino county residents age 16 and older had received at least one vaccine dose, compared with 40.4% of Asian residents, 38.1% of American Indian/Alaska native residents and 37.1% of white residents.

This lag is especially worrying when it comes to the county’s Latino residents, who have been infected with the coronavirus and died from COVID-19 at higher rates than people in other groups.

Officials and experts have long noted that lower-income Latino neighborhoods are highly susceptible to the spread of the virus because of dense housing and crowded living conditions. A higher proportion of Latinos are also essential workers who are unable to work from home or are employed in higher-risk settings — creating more opportunities to become infected at work and then bring the virus home to family members who don’t have enough space to keep their distance.

Dr. David Hayes-Bautista, a professor of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, said that unless the structural inequities are addressed, “when the next pandemic hits ... we’ll see, unfortunately, the same tragic results.”

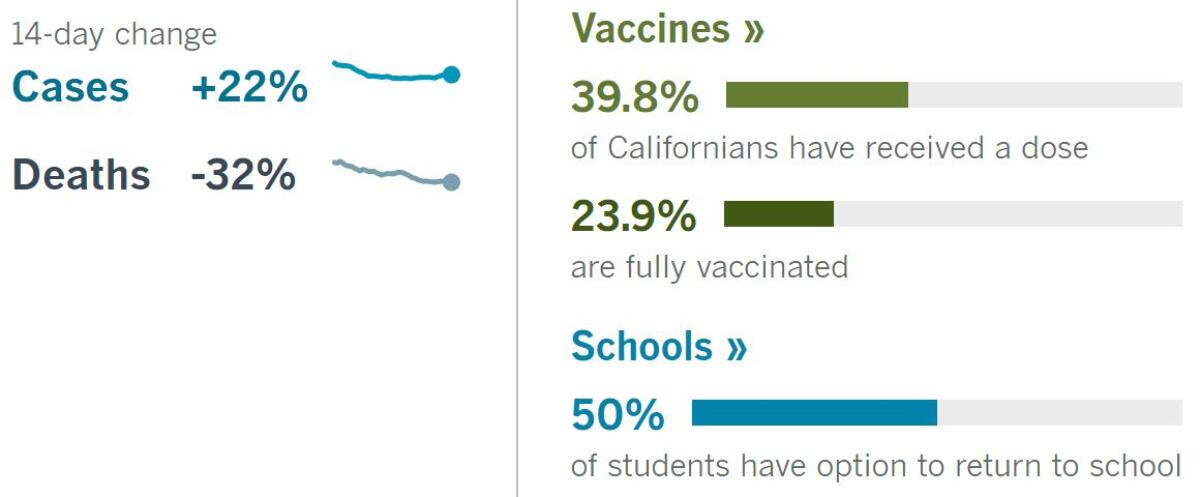

By the numbers

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 6:21 p.m. Thursday:

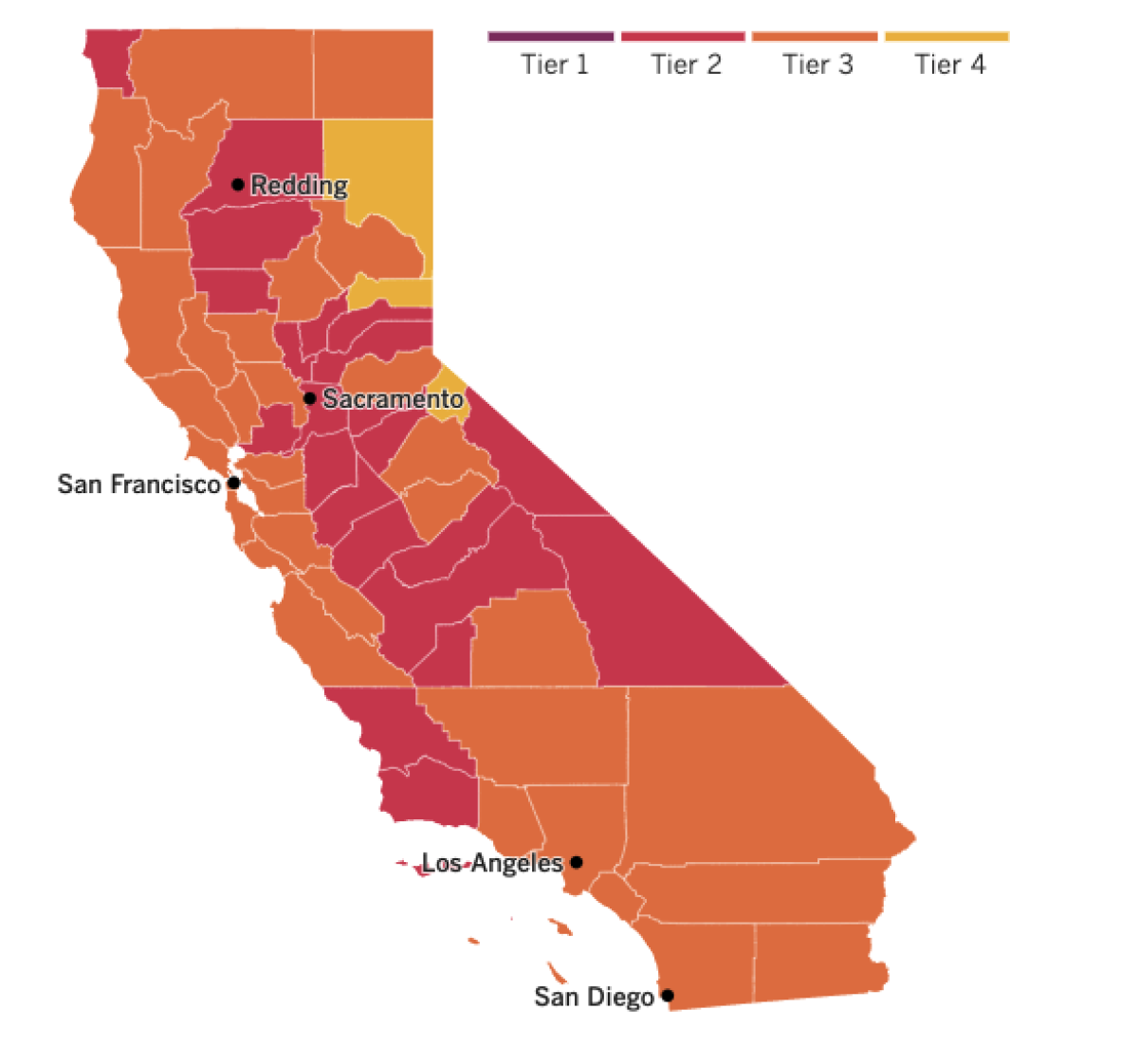

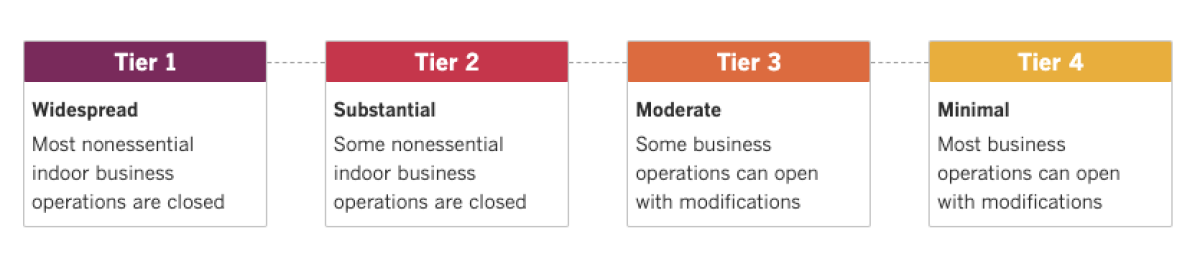

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Across California

A majority of workers would like to be back in the office soon, surveys show, but so far only one in four have returned.

California employers and landlords are betting that will change as vaccinations increase and virus fears recede, writes my colleague Roger Vincent. Yet demand to rent space in L.A. office buildings continues to shrink.

“By the stats, it’s not that encouraging,” said broker Todd Doney of real estate services company CBRE. “We certainly have work ahead of us to get through this. ... But when the governor announced no more COVID restrictions on June 15, that’s light at the end of the tunnel for me.”

Signings of office leases have been falling for about a year as companies sent employees home to telecommute or laid them off in the face of a sharp economic downturn spurred by the coronavirus.

Overall, the office vacancy rate in the county reached 17.2% in the first quarter of 2021 — the highest level since early 2012. Landlords believe more people will come back to the office over the summer, especially after Labor Day.

Bert Dezzutti, head of Southern California operations for Brookfield Properties, the dominant office landlord in downtown L.A., said tenants in the company’s high-rises have been inhabiting only about 12% to 16% of their space. He expects that number to climb now that local health officials have eased restrictions so that nonessential businesses can operate at 50% of the capacity for their space.

In Sacramento, in response to recent court rulings, state public health officials have lifted limits on indoor religious services at places of worship. They said the capacity limits on the number of people who can attend indoor services are still strongly recommended, just not mandatory.

Last week, the Supreme Court, citing religious freedom, narrowly ruled that the state may not prevent people from gathering in homes for Bible study and prayer meetings. In the 5-4 order, the court’s conservative justices noted that the state allowed businesses to reopen while more strictly restricting religious gatherings.

In a similar decision in February, the Supreme Court struck down the state’s overall ban on indoor church services during the pandemic.

Meanwhile, in Palo Alto, Stanford researchers have begun testing the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine in children ages 2 to 5.

“We want to protect children just as we want to protect adults from this disease,” said Dr. Yvonne Maldonado, the pediatric infectious diseases expert leading the trial. “The goal is to have a pediatric vaccine available for all age groups from 6 months of age to adulthood.”

About 76 million Americans have been fully vaccinated against the coronavirus, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but children remain unprotected. Currently, the Pfizer vaccine is available for people age 16 and older, while the Moderna vaccine is available to those 18 and older.

The first phase of the Pfizer study is geared toward finding a safe dosage for preschool-age children. The second and third phases will then assess whether that dose works.

Stanford is one of five nationwide sites participating in the trial, and the only one on the West Coast. People interested in signing their children up for the trial can enroll here.

See the latest on California’s coronavirus closures and reopenings, and the metrics that inform them, with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Around the nation and the world

When plotted on a graph, the curve of Bhutan’s COVID-19 vaccination drive shoots upward from the very first day, surpassing Israel, the United States, Bahrain and other countries known for their comparatively fast vaccine rollouts.

While those countries took months to reach where they are, Bhutan’s vaccination campaign is nearly finished — just 16 days after it began.

The tiny Himalayan kingdom wedged between India and China has vaccinated nearly 93% of its adult population. Overall, 62% of its 800,000 people have had their shots.

The rapid vaccine rollout puts the tiny nation just behind Seychelles, which has given shots to 66% of its population of nearly 100,000 people.

Bhutan’s small population helped it move fast. Yet its success has also been attributed to dedicated citizen volunteers and an established cold storage system used during earlier vaccination drives.

So far, the country has recorded 910 coronavirus infections and one COVID-19 death.

Government officials in other countries dream of such success.

In Thailand, a recent outbreak of the virus at nightspots in Bangkok has sent new infections surging, suggesting the country may have been lulled into a false sense of security before mass vaccinations begin.

Less than 1% of Thailand’s 69 million people have been vaccinated.

For much of last year, Thailand had fought the disease to a standstill, with low infection and death rates envied by more developed countries.

Now the daily infection numbers are rising fast. On Wednesday, 1,335 new cases were confirmed, taking the total to 35,910, with 97 deaths. While that is much better than most other countries, Thailand’s cases in the first three months of this year are triple what the country had in all of 2020.

The new outbreak has spread among mostly young, affluent and mobile Thais, and some of the newly infected had the more contagious variant first identified in the U.K.

In the U.S., new travel-related research suggests that airlines could sharply reduce the risk of being infected by the coronavirus on a flight by keeping the middle seat empty.

Models suggest that the risk of coming in contact with the virus dropped by as much as 57% if airlines limited passenger loads on both single-aisle and wide-body jets, compared with full occupancy, according to a study published by the CDC. The models the study was based on were created before the pandemic, so requirements to wear face masks on flights were not accounted for.

Although airlines have touted research — sometimes funded by the industry — showing low risks during travel, there have been studies showing coronavirus transmission can occur on flights even when passengers were wearing masks.

The study’s results may be too late for U.S. travelers. Delta Air Lines Inc. will resume selling middle seats on May 1. Delta is the last U.S. carrier to lift a social-distancing policy that began more than a year ago.

The CDC’s general guidance on travel continues to recommend that people delay travel until they are fully vaccinated because doing so “increases your chance of getting and spreading COVID-19.”

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Why is Johnson & Johnson’s COVID-19 vaccine the only one associated with a rare type of blood clots?

Actually, it’s not. AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine has been linked to the blood clots in the United Kingdom and Europe, where the two-shot regimen is authorized for use.

These cases are highly unusual because they occur in people with low levels of platelets, the raw material for clots.

The AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson offerings have something in common: Both use an adenovirus to transport their cargo into cells.

Adenoviruses can cause cold-like symptoms, and since they know how to get inside cells, scientists recognized they could be harnessed to use in vaccines. The one used in the J&J vaccine has been genetically modified so that it’s unable to copy itself and make people sick.

Scientists suspect the adenoviruses may have something to do with the rare type of blood clots seen overseas and in seven cases reported in U.S. patients who received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. Those reports prompted officials to recommend putting the J&J vaccine on hold until they could learn more about the risk.

It’s not at all clear why adenoviruses might trigger a biological process that ends in a life-threatening blood clot. In all likelihood, officials will make a decision about resuming use of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine before they figure it out. Regulators in Europe said they think the benefits of the J&J product outweigh the risks.

The other two vaccines authorized for use in the U.S. — one from Pfizer and BioNTech, the other from Moderna — use mRNA technology instead of adenoviruses. To date, no cases of this type of rare blood clot have been linked to people who got mRNA vaccines.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Keep in mind that supplies are limited, and getting one can be a challenge. Sign up for email updates, check your eligibility and, if you’re eligible, make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Need more vaccine help? Talk to your healthcare provider. Call the state’s COVID-19 hotline at (833) 422-4255. And consult our county-by-county guides to getting vaccinated.

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.