Coronavirus Today: Our century-old mask wars

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Amina Khan, and it’s Tuesday, Dec. 29. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

The pitched political battle over masks may feel like a quintessentially 2020 kind of conflict. But as it turns out, the anti-mask movement is more than a century old. Columnist Gustavo Arellano takes us back to 1919, when the world was facing another devastating global outbreak: the so-called Spanish flu, which is estimated to have infected a third of the world’s population and killed at least 50 million.

Back then, more than 700 concerned citizens and doctors signed a petition asking the Los Angeles City Council to enact a mask mandate to combat the pandemic, or “the disease will come back again, and will exact a heavier toll than ever.”

But councilmembers wouldn’t budge. One said the masks left the wearer “breathing in the foul air which they exhale.” Another snarked that he might have been more sympathetic “if the doctors would come through and agree on some one thing, or if any of them could agree at all.” A third said he would “not propose to take the advice of a lot of outsiders.”

L.A. weathered the flu pandemic better than most major American cities, largely thanks to City Health Commissioner Dr. Luther Powers, who shut down businesses and schools early on, even when others did not. But Powers had a chance to save even more lives by implementing a mask ordinance — and he didn’t.

If Powers had required everyone to wear masks in public, that “would’ve had an impact,” said J. Alexander Navarro, a medical historian at the University of Michigan.

Widespread mask use in L.A. seemed imminent when the Spanish flu hit California in the fall of 1918, Arellano writes. San Francisco issued an order for people to wear them outside their homes, and San Diego required them for anyone serving the public. Gov. William D. Stephens urged Californians to wear masks, saying they offered “but little discomfort and means a service rendered to our fellow-men and to our country.”

These messages appear to have had an effect: The Times reported on Oct. 23 that masks in L.A. “were quite common in large offices ... where the general public is coming and going all day in numbers.”

Mayor Frederick Woodman even brought a resolution to the City Council to enforce mask wearing, but Powers balked and the enforcement measure failed. Instead, the council passed a measure advising the public to wear masks, but not requiring it.

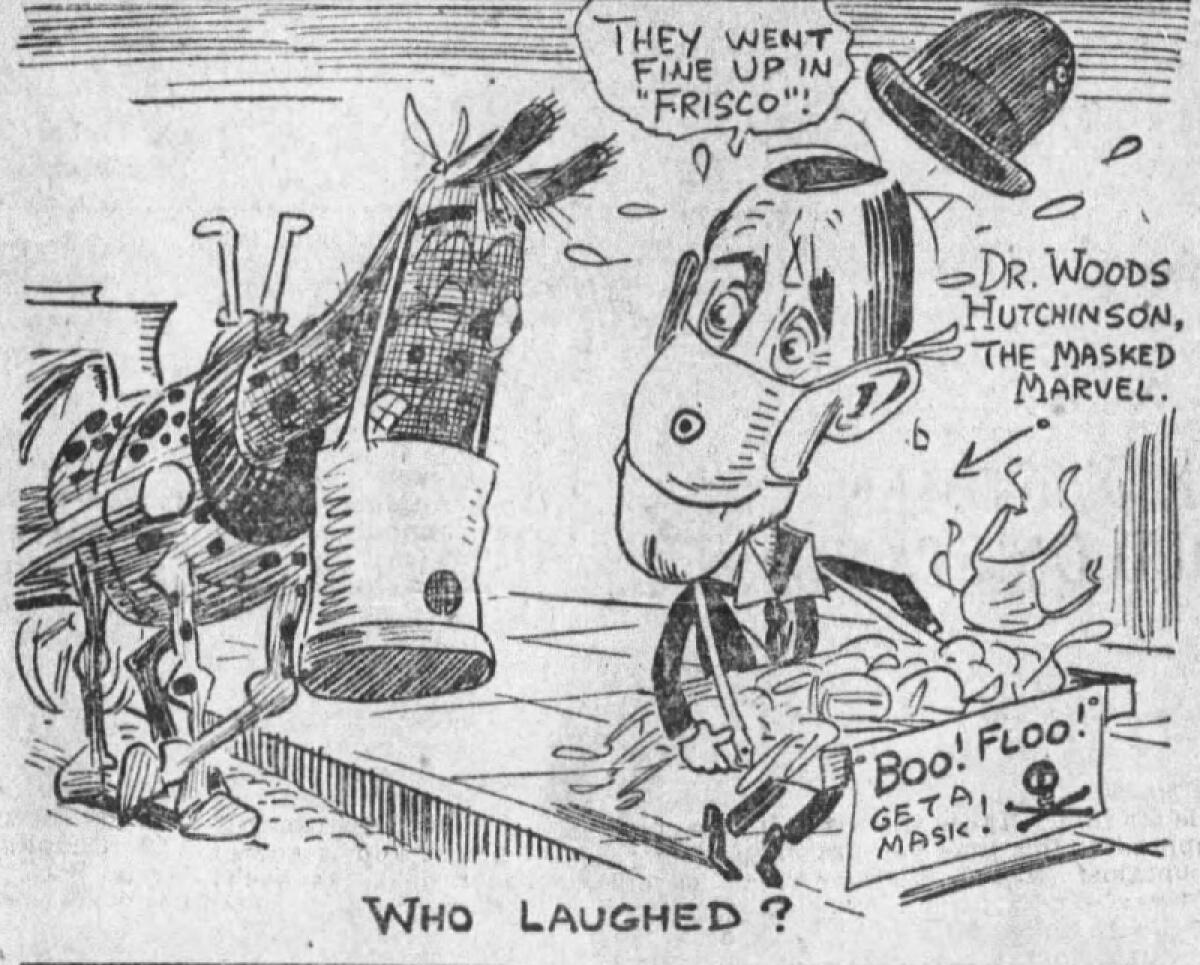

The window of opportunity, it seemed, had closed. The council soon became hostile to a mask mandate. This paper openly called masks “muzzles” and published editorial cartoons mocking their advocates. In a Dec. 1, 1918, editorial titled “Adios ‘Flu’ Scare!” the paper’s editorial board wrote that “the real sufferers are the men and women whose incomes have been stopped, whose businesses have been all but ruined.” Sound familiar?

Little did they know that the city was about to be overwhelmed by a second wave of influenza. In January, Powers finally wrote up a mask mandate but ultimately did not back its passage.

Barbara Ferrer, L.A. County’s current public health director, has explained that disagreements among officials have undermined their authority. “As soon as there’s a sense that there’s not unity — that we’re not all speaking with one voice — [it] creates a different kind of confusion and, in some cases, has given rise to a lot of defiance.”

“That’s a disaster for us,” she said.

Some of those lessons from more than 100 years ago are being relearned — the hard way.

By the numbers

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 5:24 p.m. PST Tuesday:

Track the latest numbers and how they break down in California with our graphics.

Across California

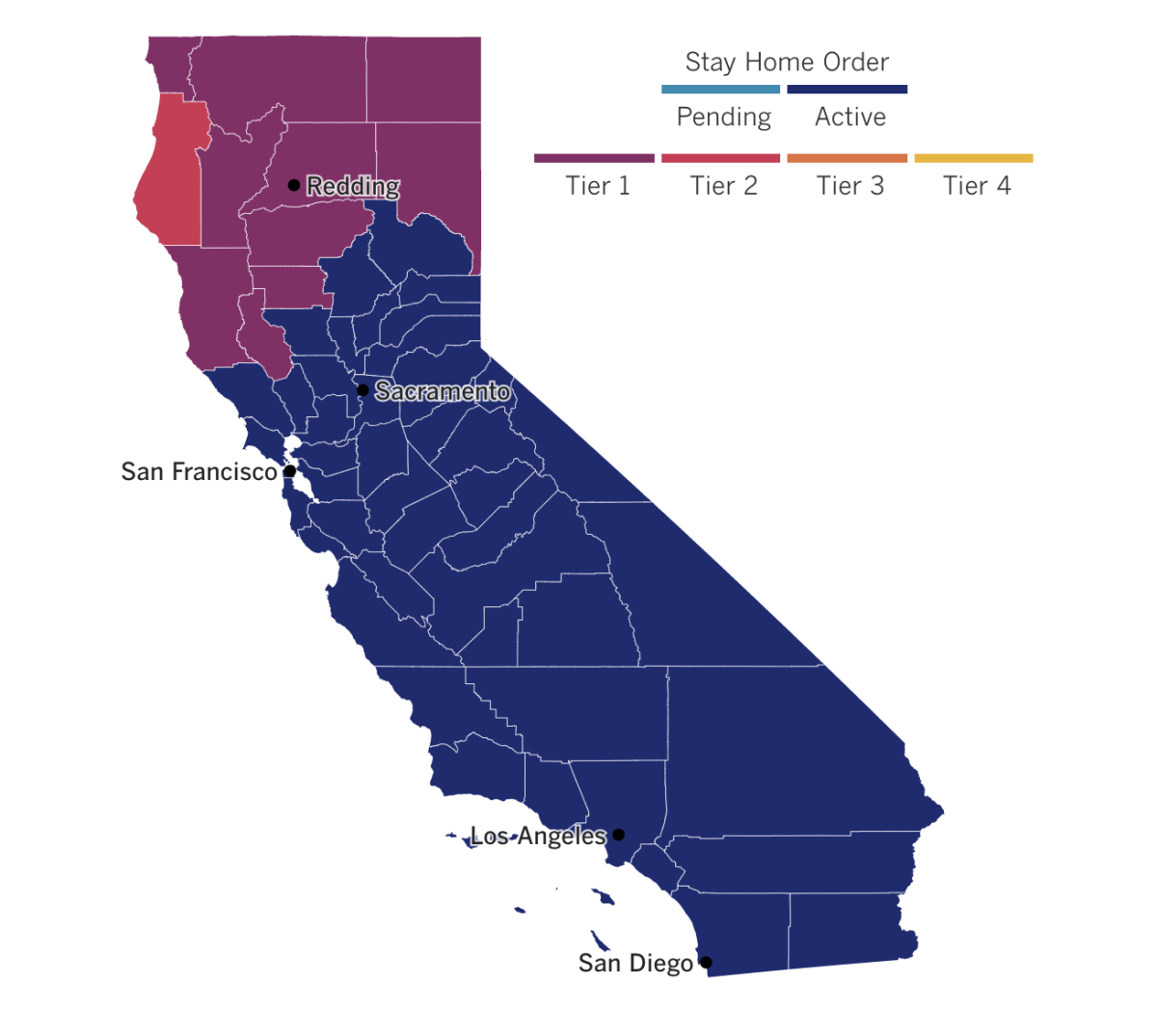

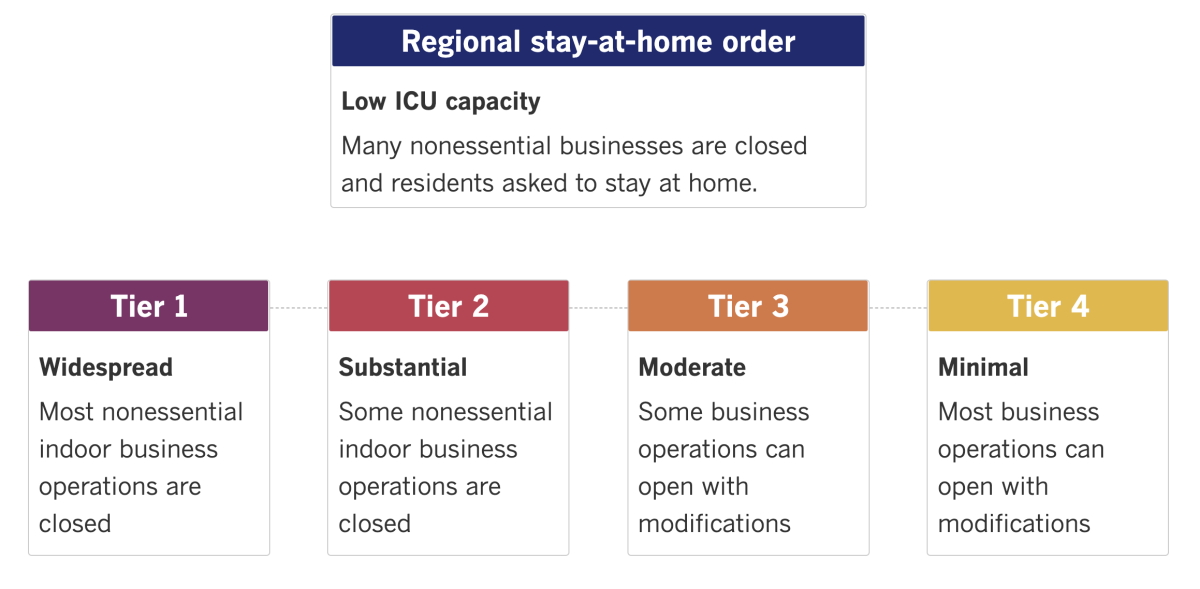

It’s official: Strict limits on businesses and activities will stay in place in Southern California and the San Joaquin Valley as COVID-19 patients pour into the regions’ hospitals. The extension of the regional stay-at-home order affects 23 hard-hit counties that are home to the bulk of California’s population, including Los Angeles, Orange, San Bernardino, Riverside and San Diego counties. The restrictions include reduced capacity at retail stores; the closure of personal care services, such as barber shops and nail salons; the shuttering of museums and zoos; a ban on most gatherings; and a suspension of outdoor restaurant dining.

While the extension wasn’t a surprise — the decision is based on intensive care unit bed availability, which has been essentially nil in both regions — it does drive home what a precarious state California is in.

The state recorded 66,811 new coronavirus infections on Monday — a tally that, with a backlog from the long Christmas weekend, marks a new daily high. And officials expect there will be yet another wave of new infections stemming from winter holiday gatherings. More hospitalizations will follow two to three weeks later.

That future is filling many doctors and nurses with dread, as they’re already running low on much-needed supplies. Take oxygen, to which most of us don’t give a second thought but which hospitals need to keep critically ill COVID-19 patients alive. Problems with oxygen supply led at least five hospitals in L.A. County to declare an internal disaster, closing their facilities to all ambulance traffic.

The problem is manifold: There’s a shortage of oxygen itself, because COVID-19 patients need 10 times the amount non-COVID patients require. There’s a shortage of canisters, which patients need in order to return home. And aging hospital pipes are literally breaking down due to the enormous amounts of oxygen that need to be distributed around the building. In fact, some hospitals have moved patients to lower floors because it’s easier to deliver oxygen there without needing the pressure to push it up to higher floors, said Dr. Christina Ghaly, L.A. County’s health services director.

And oxygen is just one example of the way Southland hospitals are stretched to the breaking point. On Sunday night at Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center, there was not a single bed available for at least 30 patients who needed intensive or intermediate levels of care. Some patients, including the very ill who required oxygen, waited 18 hours to get into the ICU. Hospitals drowning in COVID-19 patients have placed some patients in conference rooms and gift shops.

Almost all hospitals in L.A. County are being forced to divert ambulances elsewhere. “But soon, there won’t be any places for these ambulances to go,” Ghaly said.

The number of people with COVID-19 inside L.A. County’s ICUs has smashed records for 16 straight days, rising to 1,449 on Sunday. “We’re at a turning point,” said Dr. Elaine Batchlor, chief executive of Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital in Willowbrook, a 131-bed facility that had 215 patients Monday. “If it continues to get worse, many hospitals will begin rationing care.”

County officials are taking new measures to try to get the virus under control. They announced Monday that anyone who traveled out of L.A. County must quarantine for 10 days once they return.

Public health officials know that they’re fighting growing fatigue over stay-at-home restrictions, and a feeling, for some, that the fight is already lost. But county leaders continue to urge people to fight the impulse to give up, because lives are at stake. A second super-surge looms, and our decisions now will influence how many become sick and how many die.

“I understand the futility that so many people are feeling right now — the idea that some people just want to throw their hands up. But we can’t think like that,” said Los Angeles County Supervisor Hilda Solis. “To be more blunt, each one of us has the power to cause or prevent death and illness among our family members, our coworkers and even strangers.”

See the latest on California’s coronavirus closures and reopenings, and the metrics that inform them, with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Around the nation and the world

The autopsy as a medical tool had been somewhat overlooked in recent decades in favor of lab tests and imaging scans — but now the pandemic is giving it a boost. At hospital morgues around the country, pathologists who dissect COVID-19’s victims are helping make sense of its strange mix of symptoms, including loss of smell and taste, skin rashes, memory loss, difficulty breathing and flu-like coughs and aches.

Early autopsies helped show that the coronavirus doesn’t just cause respiratory disease — it can attack other vital organs, too. The discovery of microscopic blood clots in deceased patients led doctors to try treating the sick with blood thinners. Autopsies also revealed that keeping patients on ventilators for long periods caused extensive lung injury, pushing doctors to reconsider how long to keep their patients hooked up to them.

“It’s really kind of a lost tool,” said Dr. Richard Vander Heide, a pathologist at Louisiana State University. And more COVID-19 clues are sure to come to light thanks to this centuries-old practice, experts say.

In Colorado, officials have discovered the first U.S. case of COVID-19 caused by the coronavirus variant that has sparked alarm in the United Kingdom, Gov. Jared Polis said Tuesday. The variant was found in a man in his 20s who is in isolation southeast of Denver and has no travel history, officials said.

Scientists in the U.K. say that the new variant, which has a distinct set of 17 genetic alterations, appears more contagious than previously recognized strains of the virus. Many scientists, however, have resisted that view, pointing out that there are other ways to explain the variant’s rapid spread in England. For example, it may simply have been the first to start circulating in the area; it’s also possible that it was turbocharged by super-spreader events through dense communities and among those less likely to wear masks and socially distance.

There’s a lot we still don’t know about this variant, but so far, officials say there’s no indication that the new strain makes people sicker, and no evidence that the COVID-19 vaccines authorized in the U.S. will be any less effective against it.

British hospitals, meanwhile, are scrambling to make space for COVID-19 patients as cases continue to soar despite tough new restrictions meant to impede the new variant. Officials have shuttered nonessential shops, barred indoor socializing and limited restaurants and pubs to takeout operations in a swath of England home to 24 million people. More parts of England might have to be put under the toughest level of restrictions if case numbers don’t fall, officials said.

“With the numbers approaching the peaks from April, systems will again be stretched to the limit,” said Dr. Nick Scriven, immediate past president of the Society for Acute Medicine.

In Iran, home to the Mideast’s worst COVID-19 outbreak, a women’s group is looking to empower its members by helping them make and sell face masks. The organization — whose name, Bavar, means “belief” in Farsi — was formed in 2016 to help women looking for work make handicrafts with donated sewing machines, and it gave widows and others a way to earn cash in an anemic economy. But as the pandemic reduced the demand for handicrafts, women in Bavar have made a savvy pivot to making cloth face masks.

Elham Karami works five days a week to support her two sons. She said she makes around 10,000 rials (about 3 U.S. cents) for each face mask she sews. “I am grateful for this [organization] because they turned me to a skilled tailor for free,” Karami said. “They allowed me to use a sewing machine to learn how to sew. They also provided materials for me to work on.”

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: When will I get my stimulus check, and how much am I getting?

Despite his own objections, President Trump signed a $2.3-trillion spending bill on Sunday that keeps the government going and includes nearly $900 billion in stimulus for households and businesses struggling during the pandemic. My colleague Andrew Khouri brings you some key details on what we know about what’s coming.

If the IRS has your direct deposit information on file, you will probably see the money quickly. Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin said on Twitter Tuesday that “payments may begin to arrive in some accounts by direct deposit as early as tonight and will continue into next week.” Paper checks will hit the mail starting Wednesday, and people will be able to see their payment status soon on the IRS website.

As for how much is coming: People who file individually and have an adjusted gross income of up to $75,000 will get $600. That amount is gradually reduced for individuals who earn more. Joint filers will get a full payment of $1,200 ($600 per person) if their joint adjusted gross income does not exceed $150,000.

Trump has called for Congress to increase the payments from $600 to $2,000. Democrats have supported the idea, but congressional Republicans have blocked previous efforts to spend more. One expert said it’s unlikely such a proposal would make it through the GOP-controlled Senate. Today, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell blocked Democrats’ push to bring the bigger relief checks up for a vote immediately, saying the chamber would “begin a process” to address the issue.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them.

Resources

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask. Here’s how to do it right.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.